Both language and music are highly ordered systems of communicative expression. Even so, language is by no means merely a structure for encoding, transmitting, and decoding information, and music is much more than a framework for the inscribing, performing, and hearing of sound and rhythm. Through acts of seemingly unbounded artistic creativity, language and music separately stimulate flights of human imagination as few other influences can. Then when combined together in song, language and music uniquely plumb the depths of the soul. It is little wonder that Scripture repeatedly urges God’s people to “Sing to the LORD a new song” (Ps 96:1–2, 98:1, 149:1; Isa 42:10).1

Under the surface of almost every formal treatment of songwriting—sacred or secular—lies an unstated assumption: the language of the finished work will be the composer’s own. That is to say, the composer uses his or her first language (L1) to write lyrics. This basic L1 orientation holds for music translation studies as well, which address translation from a second language (L2) to the translator-composer’s L1.2 In sharp contrast, L2 songwriting—the composition of original L2 songs independent of any L1 edition—is a nearly uncontemplated phenomenon.3

The present study is an outgrowth of my reflections upon writing hymns in Chinese while teaching in a Chinese language seminary program in Asia. The following sections evaluate my songwriting experiences from the twin perspectives of language and music. Other Chinese songwriters can directly apply my findings to their work. Additionally, those who are working in other language environments can adapt the language typology-based approach below to focus and further hone their own craft of L2 song- writing. My aspiration is that the result will be a surge in L2 song- writing that breaks through barriers of language so that every person may sing praise to God.

Chinese Poetic Influences upon Songwriting

Although theoretical linguists can use identical tools and techniques to study both Chinese and English, the two languages are quite different typologically. Some of the variances that bear directly upon composition of poetic song lyrics appear in the table below and provide a framework for the following discussion.

| English | Chinese | |

| writing system | alphabetic | logographic |

| morpheme | word | syllable |

| basis of speech rhythm | stress | syllable |

| rhyme | scarce | abundant |

| repetition tolerance | low | high |

| tone function | non-lexical | lexical |

Writing System

To a native English speaker, whose language employs only 26 alphabetic symbols for the vast majority of written expressions, the 54,678-symbol set of Chinese can seem like a linguistic monstrosity.4 Although this figure results from a recent exhaustive attempt to count the logograms developed since ancient times for Chinese, currently only about 7,000 characters remain in active use in China. The 2,500 most frequently written characters account for almost 98% of those that appear in corpus linguistics studies.5 This more limited set of common characters obviously still constitutes a significant learning burden and may only reinforce the bias against intentional training in literacy manifested in some theories of language acquisition.6 Yet in the face of the difficulty of learning Chinese characters, command of the written language is essential for meaningful social interaction within highly literate Chinese societies. In addition, literary skills contribute to developing a “feel” for the language, an intuitive grasp of how Chinese works as a system. Of course, reading and writing ability are important aids to song- writing in Chinese.

Morpheme

An important systemic aspect of Chinese is that each written character corresponds to one spoken syllable.7 Moreover, each character normally conveys meaning both in isolation and in combination with other characters; thus, the lowest level of meaning (the morpheme) is the syllable in Chinese rather than the word as in English. Due to the resulting informational density of Chinese syllables, 12% of Chinese words are monosyllabic, 74% are disyllabic, and only 14% of words are lengthier than two syllables,8 while data from an English corpus linguistics study indicates that more than 40% of English words string together three or more syllables.9

The fact that fully 86% of Chinese words only have one or two syllables presents certain advantages to the songwriter. For example, lyrics for short musical phrases of equal length are theoretically easier to compose in Chinese than in English. Thus not only consecutive phrases within a song verse, but also multiple verses within a song are easier to match with set musical patterns in the process of composition. Furthermore, many monosyllabic words have disyllabic equivalents or near-equivalents, thus allowing shifting between one- and two-syllable synonyms as needed according to rhythm and rhyme considerations.10

Basis of Speech Rhythm

The strongly disyllabic nature of Chinese affects speech rhythm, in that syllable lengths are relatively even. The syllable- timed speech of Chinese stands in marked contrast to the stress- timing of English. Thus strong, stressed syllables govern the meter of English pronunciation rather than the syllable.11 Deliberate patterning of stress in English poetry gives rise to iambic (weak- strong), trochaic (strong-weak), dactylic (strong-weak-weak), anapaestic (weak-weak-strong), and other categories of meter, which composers can manipulate for poetic effect.12 Maintaining patterns of stress across the boundaries of words challenges the creativity of the English-language poet.

Returning now to consideration of Chinese, syllable timing of short words makes the language almost exude rhythm in comparison to English, in that composing poetic verses with identical numbers of similarly stressed syllables is relatively natural.13 There seems to be a particular cultural preference, inherited from more than two thousand years of poetic tradition, for five- and seven- character forms. In song, the seven-syllable line readily adapts to music in 4/4 meter with a trochaic-style rhythmic pattern, allowing a rest on the eighth beat for breathing.14

Rhyme

The syllable-centric principle that blesses Chinese with natural rhythm also bestows upon the language far more abundant rhyming resources than those of English. According to Duanmu San, Mandarin Chinese has 413 possible syllables, of which 386 are common.15 The syllables of Mandarin fall into a very limited number of rhyming categories as delineated in rhyming dictionaries. The table below lists 18 rhyming groups in the order employed in 《诗韵新编》 Shīyùn Xīn Biān, with a theme rhyming character and pin- yin transcriptions of the final sounds of the characters within each group.16

| 1 | 麻 | a, ia, ua | 7 | 齐 | i (qi) | 13 | 豪 | ao |

| 2 | 波 | o, uo | 8 | 微 | ei, ui | 14 | 寒 | an, ian, uan |

| 3 | 歌 | e | 9 | 开 | ai, uai | 15 | 痕 | en, in, un, ün |

| 4 | 皆 | ie, ue | 10 | 模 | u | 16 | 唐 | ang, iang, uang |

| 5 | 支 | i (zhi) | 11 | 鱼 | ü | 17 | 庚 | eng, ing |

| 6 | 儿 | er | 12 | 侯 | ou, iu | 18 | 东 | ong, iong |

Chinese linguists do not uniformly agree that all sounds in each category actually rhyme with each other according to modern standard pronunciation; for instance, Duanmu San divides category 15 into separate sound sets: en, un and in, ün.17 My L1 English- conditioned ear hears the “a” sounds of category 14 differently enough to separate ian (with the “a” sound of “pan”) from many an and uan (with the “a” sound of “wand”) sounds. I also doubt that the sounds of category 17 make fitting rhymes: eng (rhymes with the English “lung”) and ing (as in English “king”). Furthermore, probably because English does not have the ü sound of category 11, my sense is that categories 10 and 11 rhyme with each other to some degree.18 Thus, my category additions and subtractions result in expanding the scheme in the table above to 20 basic categories of rhyme. Many words especially useful for Christian songwriting fall within the second most frequently encountered rhyme among the most commonly used Chinese characters, category 10 (the “u” sound): 父 fù “Father,” 主 zhǔ “Lord,” 耶稣 yēsū “Jesus,” 基督 jīdū “Christ,” 吩咐 fēnfù “to command,” 门徒 méntú “disciple.”19 Other than intra-category rhymes such as these that cohere with the organizational scheme of Chinese rhyming dictionaries, it seems to me that there are also acceptable cross-category near-rhymes united by a shared vowel sound: for example, 浸礼 jìnlǐ “immersion baptism” in category 7 i, 福音 fúyīn “gospel” in category 15 in, and 圣灵 shènglíng “Holy Spirit” in category 17 ing.

All this is to say that it is far, far easier—perhaps even orders of magnitude easier—to rhyme in Chinese than in English. There are indeed English rhyming dictionaries to assist in locating rhymes for the over 15,800 syllables attested in English.20 However, a complicating factor in composing acceptable rhyming lyrics in English is that multisyllabic words must rhyme more than one syllable.21 This points to yet another advantage of Chinese rhyme for the songwriter. All Chinese rhymes are only one syllable in length.

Repetition Tolerance

Chinese to a greater degree than English customarily employs the repetition of words for discourse cohesion, whereas the English preference is for variation.22 Therefore even translations in- to Chinese reuse terms when repetition was not present in an original English text, as seen in the following Francis Bacon quotation focusing upon the concept of “studies” (in Chinese: 学问 xuéwèn):

To spend too much time in studies is sloth; to use them too much for ornament, is affection; to make judgment wholly by their rules, is the humour of a scholar. They perfect nature, and are perfected by experience . . .

把时间过多地花费在学问上,是怠惰;把学问过多地用作装饰,是虚伪;完全按学问的规则来判断,则是书呆子的嗜好

。学问能使天性完美,而经验又能使学问完善。

The first 学问 term directly renders “studies,” and the second through fourth 学问 repeat “studies” rather than use a pronoun as in English. The final 学问 in the Chinese translation reintroduces the omitted subject of Bacon’s passive voice expression: “[studies] are perfected” = 使学问完善. Therefore the Chinese 学问 term actually appears one more time than the original word “studies” and all of its substitutes.23

A root cause of tolerance for repetition may include custom- ary Chinese employment of reduplication, which alters word meaning. For example, alone the character 大 dà can mean “great,” but the pair 大大 dàdà means “greatly.” Chinese words or phrases can repeat as a thematic linking device in separate poetic lines or function in a refrain-like manner.24 Of course repetition strategies exist in works of English poetry as well. Yet the observed greater tolerance of Chinese for verbatim repetition suggests that a Chinese songwriter need not be as reticent as an English lyricist to recycle identical expressions within a single song.

Tone Function

Within every syllable of Chinese, the voiced pitch of vowels carries semantic information.25 Native speakers of non-tonal languages who begin learning Chinese soon discover that very common words with identical consonant and vowel sounds differ only in tone, as in the case of several Chinese city names: 北京 běijīng (Beijing) / 背景 bèijǐng (background), 上海 shànghǎi (Shanghai) / 伤害 shānghài (to injure), 成都 chéngdū (Chengdu) / 程度 chéngdù (extent).

At first glance it would seem that tone would play absolutely no role in the composition of song lyrics, in that the pitch of sung musical notes would override the pitch of tones required for the recitation of lyrics without music. Further considering the influence of tone in the singing of Chinese lyrics requires greater focus upon Chinese hymnody, which is the task of the following section.

Summary

Accepting for now that tone will return as a topic of discussion below, it is helpful briefly to restate the overall influence of major features of the Chinese language upon songwriting. Each feature of the Chinese language surveyed, including its logographic writing system, its consistent use of syllables for its morphemes, its syllable- timed speech rhythm, its considerable ease of rhyme, and finally its tolerance of repetition, all confer great advantage upon the lyricist. This is not necessarily to claim that songwriting in Mandarin is easy, for at the end of the day, of course, one must marshal the poetic resources of Chinese to actual artistic effect. However, awareness of the inherent suitability of the language for composing lyrics should indeed inspire more L2 (and L1) Chinese songwriting. Thus it is to hymnody that this essay now turns.

Chinese Hymnody

Hymn Lyrics as Poetry

The predominant expression of Christianity in contemporary China is Protestantism, the foundation for which western missionaries laid before their expulsion from the mainland in 1949. Missionaries brought with them the music of the western church and therefore translated western hymns into Chinese. A fundamental challenge they faced was musical: western church music was heptatonic, and Chinese music was predominantly pentatonic. Thus the fourth and seventh notes of major scales proved difficult for Chinese people to sing.26

The widely divergent dialects of Chinese presented another challenge to singing, for hymn lyrics translated in one region of China would be legible but not necessarily comfortably singable elsewhere due to loss of rhyme. The table below helps to illustrate the dialectical effect upon the rhyme scheme for the first verse of the hymn “Praise to the Lord, the Almighty,” using English as a standard of comparison.27

| English | ||

| Praise to the Lord, the Almighty, the King of creation! | A | |

| O my soul, praise Him, for He is thy health and salvation! | A | |

| All ye who hear, | B | |

| Now to His temple draw near; | B | |

| Praise Him in glad adoration! | A | |

| Mandarin Chinese | Hanyu Pinyin transliteration | |

| 讚美!讚美!全能真神宇宙萬有君王。 | Zànměi! Zànměi! Quánnéng zhēnshén yǔzhòu wànyǒu jūnwáng. | A |

| 我靈頌主,因主使我得贖,賜我健康。 | Wǒ líng sòng Zhǔ, yīn Zhǔ shǐ wǒ dé shú, cì wǒ jiànkāng. | A |

| 聽主聲音, | Tīng Zhǔ shēngyīn, | B |

| 都來進入主聖殿, | Dōu lái jìnrù Zhǔ shèngdiàn, | C |

| 歡然向主恭敬讚揚! | Huānrán xiàng Zhǔ gōngjìng zànyáng! | A |

| Southern Min (Hokkien) Chinese | Pe̍ h-ōe-jī transliteration | |

| 讚美全能的主上帝,造化的大君王! | O-ló chôan-lêng ê Chú Siōng-tè, chō- hoà ê tōa kun-ông! | A |

| 祂做你大氣力拯救,我心神當尊崇! | I chòe lí tōa khuì-la̍ t chín-kiù, Góa sim-sîn tio̍ h chun-chông! | A |

| 聽見的人, | Thian-kìn ê lâng, | B |

| 當入祂聖殿讚美 | Tio̍ h jı̍ p I sèng-tiān o-ló | C |

| 與我同心歡喜稱呼。 | Kap góa tâng-sim hoan-hí chheng-ho͘. | C |

Interestingly, neither Chinese version above attempts to duplicate the English rhyme scheme.28 In fact, the Mandarin and Southern Min hymns appear to interpret the short third and fourth lines as one longer line, although they go on to employ rhyme strategies that differ from each other. If one combines lines three and four and labels them non-rhyme “X,” then the above rhyme schemes become English AAXA, Mandarin AAXA, and Southern Min AAXX (for which “XX” indicates that the non-“A” rhyme repeats). The Mandarin translation’s rhyme scheme superficially conforms to the English, while the Southern Min rhymed translation moves in a different direction entirely.

29Combining lines three and four does not match the musical logic of the source text, for each of the five English lines ends with a full-measure dotted half note. However, reorganization to four lines matches a Classical Chinese poetic convention in which the final syllable of a fourth line in a four-line set establishes the rhyme scheme of the whole set. The resulting rhyme pattern can either be AAXA or X1AX2A (for which the two non-“A” rhymes do not rhyme with each other), with the first of these two possibilities al- lowing the poet the option to rhyme the first line. Expanded to the eight lines of 律诗 lǜshī regulated verse poetry, these patterns would look like AAX1AX2AX3A or X1AX2AX3AX4A.30 Alternately, rhyming every line (as in AAAA) is acceptable.31 In Classical Chinese poetry, characters within each line must also conform to established alternating tone patterns.32 The tones of Modern Mandarin do not preserve the same distinctions as those present in earlier stages of the Chinese language; thus, employing the tone patterns of Classical Chinese poetry in the contemporary era requires the assistance of tone notations in rhyming dictionaries.33

As I was writing the first fifteen songs of my Chinese worship song corpus, I was not aware of these deeply rooted expectations of how song lyrics should rhyme, nor of intentional patterning of tones. Thus the chorus of my second song at first glance displays none of the formal characteristics of Classical Chinese poetry. Admittedly, if one extracts the refrain that is also the title of the song, the main lines have seven characters, as seen in the table below. Even so, there is no question of these lyrics fitting with traditional patterns of rhyme on one hand, or the four- or eight-line form of Chinese poetry on the other.

《哦主》 (Song 2)

| Chorus Lyrics | Mandarin Rhyme | English Translation |

| 哦主, | – | O Lord, |

| 请祢来赐我复兴 | A | Please come and revive me |

| 让我不会硬着心 | A | Don’t let me harden my heart |

| 听祢所有的命令! | A | Make me obey all you command! |

| 哦主, | – | O Lord, |

| 祢的恩典真足够 | B | Your grace is enough |

| 求祢用油膏我头 | B | I ask that you anoint my head with oil |

| 让祢爱总出我口! | B | May your love always issue from my mouth! |

| 哦主, | – | O Lord, |

| 所有荣耀归于祢! | A | All glory to you! |

However, the seven-character, four-line format does appear in my later songs: in the chorus of song 7 and the verse structure of song 9. See the two tables below.

《大卫子孙阿,可怜我吧!》 (Song 7)

| Chorus Lyrics | Mandarin Rhyme | English Translation |

| 这是我简单呼求 | A | This is my simple request |

| 雄辩言语都没有 | A | I have no eloquent words |

| 哦救主听我祷告 | B | O Savior hear my prayer |

| 向我显出祢荣耀 | B | Show me your glory |

《神,我献上生命中的一切》 (Song 9)

| Verse 1 Lyrics | Mandarin Rhyme | English Translation |

| 当我困在黑暗里 | A | When I was trapped in darkness |

| 祢大力把我拽出 | B | You powerfully pulled me out |

| 虽我亵渎全故意 | A | Though my blasphemy was completely intentional |

| 祢竟倾倒爱如雨 | B | You poured out your love like rain |

Only the verse structure of song 9 immediately above approximates Chinese expectations of alternating line rhyme in poetry, and even then, the first and third “A” lines should not rhyme with each other.

Interestingly, it was precisely these seven-character, four-line phrases that cued my lyrics editor to question my rhyme strategy. Perhaps the format of these phrases looked enough like actual Chinese poetry to raise Chinese cultural expectations of rhyme into sharper relief than with other compositions.

As for expectations generated by cultural poetic norms, it is now appropriate to return to the issue of expression of lexical tone in music. The consensus of research is that the tones of tone languages can indeed affect the composition of music. Analysis of pitch “slopes” in music and speech reveals that the rise and fall of pitch in music to some degree correlates to the rise and fall of pitch in speech.34 For example, Wee’s analysis of ten randomly selected Mandarin folk songs results in the correlation principles below.35

| two-note musical pitch sequence | ➘ | ➚ | ➙ |

| tone of first note | 1 or 2 | 3 or 4 | any |

Since song 9 provides the lengthiest example of the seven- character, four-line form in my song set, I analyzed the degree of matching of its spoken tones to music. Below is the melody for the verses of song 9, including the lyrics of the first verse.

Thus the melody generates the following sequences of six pitch changes per seven-note phrase, among which the first and third sequences are identical:

The following chart displays the degree of correlation from 0 (none) to 6 (complete) of the tones in verse lyrics with the pitch pattern of song 9. Bold type for the tone numbers highlights the tones of the characters that exhibit the tonal correlation predicted in Wee’s analytical scheme.

《神,我献上生命中的一切》 (Song 9)

| Chinese Lyrics | Tones | Correlation | English Translation |

| 当我困在黑暗里 | 1344143 | 6 | When I was trapped in darkness |

| 祢大力把我拽出 | 3443341 | 4 | You powerfully pulled me out |

| 虽我亵渎全故意 | 1342244 | 6 | Though my blasphemy was completely inten- tional |

| 祢竟倾倒爱如雨 | 3413423 | 3 | You poured out your love like rain |

| 祢话语直击我心 | 3432131 | 6 | Your word pierces my heart |

| 令我无可再推委 | 4323413 | 5 | I can’t make excuses any more |

| 我要跟随并受浸 | 3412444 | 4 | I will follow and be bap- tized |

| 终身尊主不违背 | 1113424 | 2 | All my life I will honor my Lord and not rebel |

| 所有计划和希冀 | 2344214 | 4 | All my plans and hopes |

| 都上交在祢手里 | 1414323 | 5 | I place them in your hands |

| 无论差我到何地 | 2413424 | 4 | No matter where you send me |

| 甘心顺服事奉祢 | 1142443 | 4 | I am willing to submit to serving you |

| 惟愿忠爱我天父 | 2414314 | 4 | I only want to love my Heavenly Father loyally |

| 时刻受管于圣灵 | 2443242 | 2 | Constantly under the discipline of the Holy Spirit |

| 日渐活像主耶稣 | 4424311 | 4 | Day by day living like Jesus |

| 总见证贵重福音 | 3444421 | 3 | Always bearing witness to the precious gospel |

| 直等行完旅程时 | 2322322 | 4 | I continually look ahead to finishing my journey |

| 待被唤醒见祢面 | 4443434 | 3 | When I will be awakened to see your face |

| 再也没有罪与死 | 4323423 | 4 | There will never again be sin or death |

| 喜乐颂赞到永远 | 3444423 | 3 | I will joyfully praise you forever |

It turns out that the average correlation value (the statistical mean) is 4, and the most numerous correlation value (the statistical mode) is also 4, perhaps suggesting a slightly better than random match between tone contours of music and speech.36 Interestingly, the first verse exhibits the best matching of musical and spoken pitch, causing me to question whether the tone of the lyrics influenced my composition of the melody. If so, then the pitches of the then-established melody seem to exert a diminishing feedback effect upon the writing of the lyrics for subsequent verses.

It is also entirely possible that since I am an L2 Chinese speaker whose native language lacks lexical tone, the overall influence of tone upon my composition was minimal. That said, lack of focused attention upon lexical tone in writing of lyrics for Chinese Christian worship songs may not be a significant liability, for research indicates that contemporary Mandarin music (as opposed to traditional forms of music like folk songs or Chinese opera) is not tone-conscious. Thus listeners must rely on context to understand the songs.37 A biblical and theological vocabulary set is one such element of context to assist hearers in the decoding of atonal Chinese Christian song lyrics.38

Chinese Musical Influences upon my Songwriting

An enduring musical influence dating from the beginning of my Chinese language learning has been the hymnody of 吕小敏 Lǚ Xiǎomǐn (popularly known by her first name Xiaomin), whose arresting pentatonic songs adapt and transform Chinese cultural symbolism in the service of a Christian message.39 I use one of her early songs to introduce the study of Ruth chapter 3, when Ruth faces the crisis of going to Boaz’s threshing floor at midnight to prompt him to fulfill the duties of the “kinsman redeemer.” Lyrics appear below.40

《每一天我都需要祢的帮助》

| Chinese Lyrics | English Translation |

| 每一天我都需要祢的帮助 | Every day I need your help |

| 每一分钟我都需要祢的帮助 | Every minute I need your help |

| 面对禾场我更需要祢的帮助 | When I face the threshing floor I need your help even more |

| 主我需要祢的帮助 | Lord I need your help |

| 祢来帮助,祢来帮助 | Come help! Come help! |

| 我需要祢的帮助 | I need your help! |

| 祢来帮助,祢来帮助 | Come help! Come help! |

| 我需要祢的帮助 | I need your help! |

Like me, Xiaomin writes songs without the benefit of formal training in songwriting and needs others to provide arrangements of melodies. Unlike me, she writes over 150 hymns per year!41

Perhaps an even more significant influence upon my song- writing is the music of 赞美之泉 Zànměi Zhī Quǎn Stream of Praise, a Taiwanese-American music ministry founded in 1993 and led by Sandy Yu. The group spans Chinese and American cultural spheres, in that some songs draw upon more specifically Chinese cultural symbolism and others adhere more to the predominantly English- language Christian “praise and worship” genre of music.42 It is possible that the departure of some of my songs from an Anglo- American hymn style (a certain number of verses, each followed by a chorus) is due to Stream of Praise influence. I also think it likely that Stream of Praise music is more culturally accessible to me as an American than the music of Xiaomin, thus allowing their songs to serve as a bridge for me to cross into deeper appreciation of Christian worship music in Chinese. One of the mysteries of that appreciation is that Chinese Christian worship music has become even more meaningful to me than worship music in English. An out- growth of my mysterious heartfelt connection with Chinese Chris- tian worship music is the spontaneous appearance in my life of L2 songwriting.

L2 Songwriting at the Intersection of Faith and Scholarship

As mentioned in the introduction to this essay, the phenomenon of writing songs in a second language has not generated a great deal of research. Yet as a result of his experiences in helping aspiring Japanese songwriters to pen song lyrics in English, Brian Cullen has formulated a typology of a “Good L2 Songwriter.” According to Cullen, a strong L2 songwriter possesses significant L2 language skills and is able to use simple language creatively. He or she is open to new experiences and is willing to draw upon both L1 and L2 sociocultural aspects and song norms, especially through imitating L2 songs in a creative way rather than merely through copying. The good L2 songwriter is flexible in choosing songwriting strategies and displays interest in developing new strategies, viewing songwriting as a creative writing act rather than an act of translation from L1. This songwriter requests that a language informant correct song lyrics in the mode of a teacher but self-corrects as much as possible. Despite maintaining creative “ownership” of the song, the good L2 songwriter acknowledges when rewriting is necessary and carries out songwriting projects with a strong work ethic.43

I do not cite Cullen as an exercise in self-congratulation, but reading his work after having written fifteen songs provides some encouragement that I am not too heavily burdening my lyrics editor or those who have arranged my songs for group singing. Due to the Confucian ethic of revering one’s teacher, Chinese students are normally hesitant to say “no” to a teacher or to correct the teacher when he or she is in error about some issue. Therefore I am all the more thankful for the linguistically, culturally, and spiritually sensitive assistance of my L1 Chinese language informant, who indirectly but effectively communicated that I needed to abandon work and start over on the fifteenth song.44

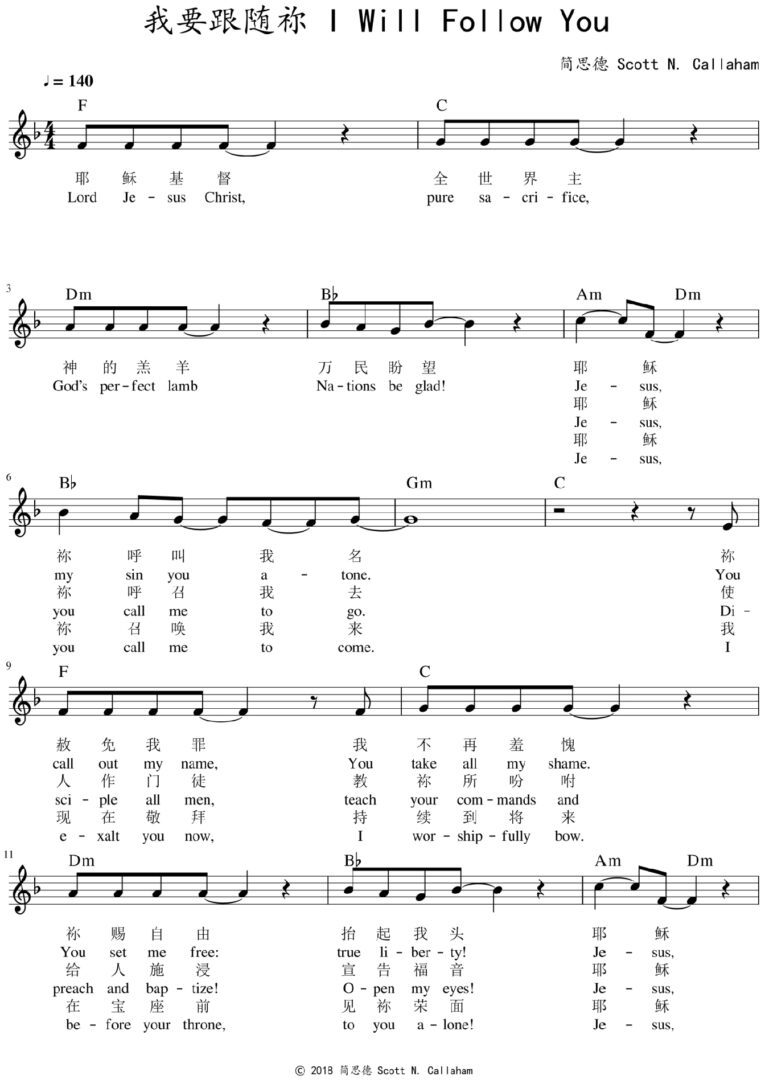

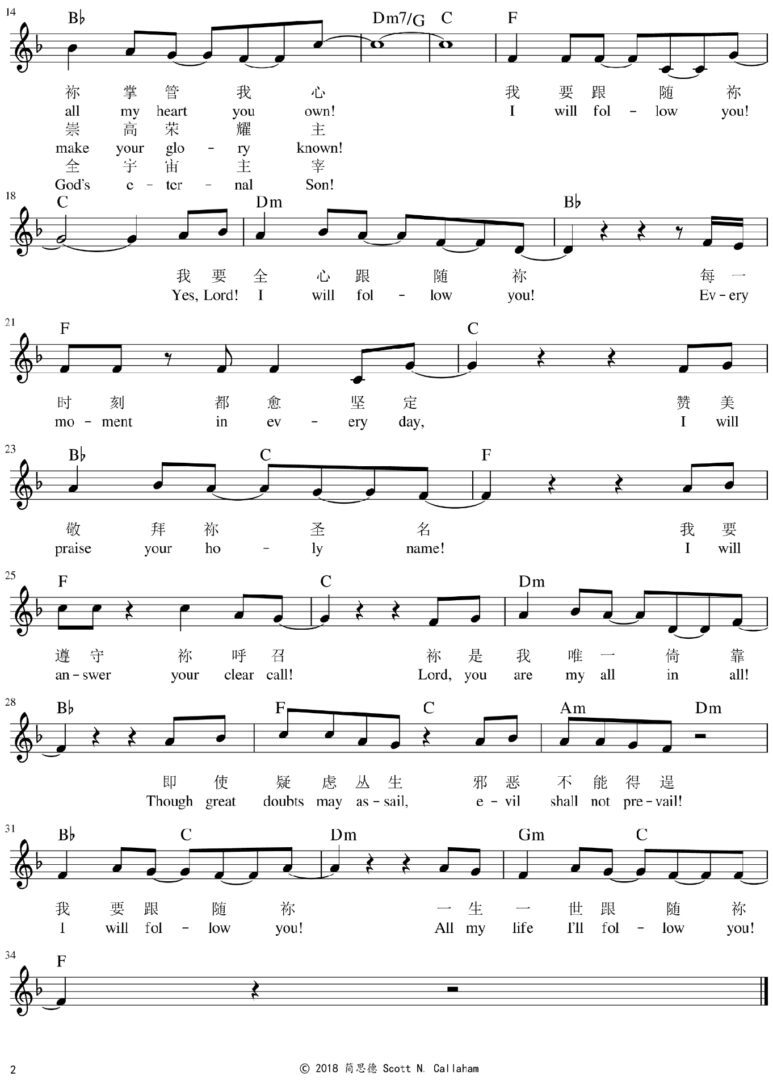

As for the final song, it provides an appropriate sort of finale for this essay. On April 3, 2018, a student spoke with me before our seminary’s Chinese chapel service, asking if I would consider writing a song to honor those who would graduate on May 19. I explained that these songs are not intentional compositions, but the idea struck me as quite God-glorifying, so I suggested that we begin praying for inspiration during the prayer meeting following chapel. After the chapel service and prayer meeting I met with our Academic Dean to tell him about the student’s suggestion, adding that I thought the most appropriate outcome would be a bilingual Chinese-English song in order to honor the English track graduates as well. Over the next ten days the song indeed came, with a few of those days required for the above-mentioned rewrite.

During the graduation ceremony, a choir composed of both Chinese- and English-track students alternatingly sang the verses first in Chinese and then in English translation, with bilingual students standing in the center to unite the two language “halves.” Accompanied for most of the presentation by piano, the choir sang through the chorus the second time a cappella and clapped on up- beats for the third time. On the second of these third times through the chorus, which according to the Chinese-English alternation pattern would ordinarily have English lyrics, the choir sang in both languages simultaneously. At that point in my debut as a music conductor I turned to the audience and invited them to sing along in the language of their choice.45 Below is the bilingual score for《我要跟随祢 I Will Follow You》 (Song 15).

While this song is indeed bilingual, like the previous fourteen compositions it is a Chinese song. That is to say, it is a Chinese song that became bilingual through translation into English. The table below displays the song’s lyrics and rhyme scheme for comparison.

| 持续到将来 | D | Continuing into the future | I worshipfully bow, |

| 在宝座前 见祢荣面 | E E | Before your throne I see your face | Before your throne, to you alone! |

| 耶稣,全宇宙主宰! | C | Jesus, Lord of the whole universe! | Jesus, God’s eternal Son! |

Chorus

| 我要跟随祢! | A | I will follow you! | I will follow you! |

| 我要全心跟随祢! | A | I will follow you wholeheartedly! | Yes, Lord! I will follow you! |

| 每一时刻都愈坚定 | B | Every moment I grow more resolute | Every moment in every day |

| 赞美敬拜祢圣名! | B | Praising and worshiping your holy name! | I will praise your holy name! |

| 我要遵守祢呼召! | C | I will obey your calling! | I will answer your clear call! |

| 祢是我唯一倚靠! | C | I depend on you alone! | Lord, you are my all in all! |

| 即使疑虑丛生 | D | Though doubt may spring up all around | Though great doubts may assail, |

| 邪恶不能得逞! | D | Evil cannot prevail! | Evil shall not prevail! |

| 我要跟随祢! | A | I will follow you! | I will follow you! |

| 一生一世跟随祢! | A | All my life I’ll follow you! | All my life I’ll follow you! |

The tables above illustrate parallelism within the similarly rhymed sections of each verse. The middle column contains a literalistic translation of the Chinese lyrics for the sake of highlighting what I judged to be possible to convey through English within the musical constraints of the song, with bold type indicating what I did not translate at all or instead altered in meaning through translation. My motivation for these changes in the process of translating the Chinese lyrics to English was to preserve the “spirit and mood” of the song at the expense of a high degree of literalism.46 Since Christian worship songs rely especially heavily upon their lyrics for the theological content that sets “spirit and mood,”47 I broke a Chinese lyrics-established parallelism pattern in order to keep similar content within the English translation. Note that according to the Chinese pattern, the first “C” line in each verse is roughly “Jesus, you call . . .” in English. The superimposed arrows indicate that “shame” attracted “you call out my name” from the first verse’s “C” line down into the following “D” line, and the lyrics of the first “D” line in Chinese raised to the first “C” line in the English translation to compensate.

In my view, the English translation of the song passes the test embodied in Peter Low’s influential “Pentathlon Principle” of song translation, in that the English verses and chorus are singable, convey the sense of the original Chinese, sound natural, and conform to the song’s existing rhythm and rhyme structure.48 The performance of the song in two languages by students from eight Asian nations, as well as the inclusion of the audience in simultaneous Chinese and English singing at the end, intentionally employed bilingualism as a symbol of juxtaposition of cultures.49 Thus the singing of the song itself anticipated the fulfillment of the visionary scene in Revelation 5 to which the final verse of the song alludes: people “from every tribe and language and people and nation” (Rev 5:9, ESV) worshiping before the throne of God and the Lamb (Rev 5:6).

I have stated above my hope that this essay will encourage more L2 songwriting in all language settings. As far as I am aware, this is the first modern study to focus specifically on Chinese L2 songwriting, especially for the sake of creating Christian worship music. Therefore even as this work breaks fresh ground in service of the worldwide Christian church, I also dare to aspire for a specific, ambitious outcome. If it is true that “a certain language demands for its best interests a certain style of music,”50 then may ever more songwriting cause heaven and earth to resound with the voices of untold millions who will sing to the LORD a new song (in Chinese)!51

- See similar expressions in Ps 33:3, 144:9; Rev 5:9, 14:3. ↩︎

- See for example Arthur Graham, “Modern Song Translation,” The NATS Journal 48 (March 1992): 15–20. ↩︎

- Brian Cullen has published several works on L2 songwriting. See the final section of this essay. Theoretically the new field of self-translation studies, for which an author of a piece and its translator are the same person, could investigate L2 songwriting as an act of L1 to L2 translation. However, to date the field has focused upon literary rather than musical texts. See Chiara Montini, “Self- translation,” in Handbook of Translation Studies, 4 vols., ed. Yves Gambier and Luc van Doorslaer (Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 2010–13), 1:306–8. ↩︎

- Missionary William Milne exclaimed, “To acquire the Chinese is a work for men with bodies of brass, lungs of steel, heads of oak, hands of spring-steel, eyes of eagles, hearts of apostles, memories of angels, and lives of Methuselahs!” (Robert Philip, The Life and Opinions of the Rev. William Milne, D.D., Missionary to China [Philadelphia: Herman Hooker, 1840], 129). ↩︎

- John Jing-hua Yin, “Chinese Characters,” in The Routledge Encyclopedia of the Chinese Language, ed. Chan Sin-wai (New York: Routledge, 2016), 51–63, esp. 57. ↩︎

- Guadalupe Valdés, Paz Haro, and Maria Paz Echevarriarza, “The Development of Writing Abilities in a Foreign Language: Contribution toward a General Theory of L2 Writing,” Modern Language Journal 76 (1992): 333–52, esp. 333. The Growing Participator Approach toward second language learning discourages development of literacy skills altogether. See Thor Andrew Sawin, “Second Language Learnerhood among Cross-Cultural Field Workers” (Ph.D. diss., University of South Carolina, 2013), 153–54. ↩︎

- Some characters can correlate to more than one possible sound, with context determining correct pronunciation. Even so, every potential reading can only be one syllable in length. Incidentally, Japanese kun readings of Chinese characters can

be multisyllabic, for example kokorozashi for 志 (zhì in Modern Mandarin). See John

H. Haig, The New Nelson Japanese-English Character Dictionary (Rutland, VT: Charles

E. Tuttle, 1997), 428. ↩︎ - Hua Lin, A Grammar of Mandarin Chinese (Munich: Lincom Europa, 2001), 55. ↩︎

- Hideaki Aoyama and John Constable, “Word Length Frequency and Distribution in English: Part I. Prose—Observations, Theory, and Implications,” Literary and Linguistic Computing 14 (1999): 339–58, esp. 353. ↩︎

- For example the single character 爱 ài means “love.” A two-character synonym that places 爱 ài first is 爱戴 àidài, while 爱 ài appears second in the synonym 热爱 rè’ài. Some two-syllable synonyms alternate the order of identical characters to communicate different levels of formality; for example, 情感 qínggǎn (more literary) and 感情 gǎnqíng (less literary) both mean “emotion.” Character

order in other synonyms can carry difference in connotation, such as these two verbs for “sheltering”: 庇护 bìhù (negative connotation, implying the sheltered one is undeserving) versus 护庇 hùbì (positive connotation, a Chinese Bible term for graciously granting protection). See Grace Qiao Zhang, Using Chinese Synonyms

(New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 1, 17, 139. ↩︎ - April McMahon, An Introduction to English Phonology (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2002), 124–28. To L1 English speakers, deviation from expected stress timing conveys the impression of a non-standard accent. See David Deterding, “The Rhythm of Singapore English” (paper presented at the Fifth Australian International Conference on Speech Science and Technology, Perth, 6–8 December 1994), 1–5. ↩︎

- Austin C. Lovelace, The Anatomy of Hymnody (Chicago: G.I.A., 1965), 11–16. ↩︎

- Liu describes the rhythm of the inherent “music” of Chinese poetry as a staccato effect. See James J. Y. Liu, The Art of Chinese Poetry (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962), 38. ↩︎

- Perry Link, An Anatomy of Chinese: Rhythm, Metaphor, Politics (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2013), 25, 38, 49, 75–76. ↩︎

- Duanmu San, Syllable Structure: The Limits of Variation (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 91. Limitation to 413 possible syllables does not imply that Chinese speakers cannot voice other sounds. For example, Mandarin Chinese lacks the “fi” sound of “wi-fi,” preventing its phonetic rendering in Chinese characters and thus its full adoption as a loan word (无线 wúxiàn, meaning “wireless,” is the

Chinese alternative). Yet L1 Chinese speakers encounter little difficulty in

pronouncing “wi-fi.” ↩︎ - 《诗韵新编》 (Shanghai: Zhonghua Book, 1965), 1. Category 5 and 7 i sounds are distinct. The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) symbols for the category 5 i are ɻ̩ and ɹ̩ , and the IPA symbol for category 7 i is i. ↩︎

- Duanmu San, The Phonology of Standard Chinese, 2nd ed. (New York: Oxford

University Press, 2007), 58. Jin Zhong grants that en and in are not identical sounds but considers them close, noting that the sounds apparently had the same pronunciation during the Tang Dynasty. See Jin Zhong, 《诗词创作原理》(Xian: Shaanxi Normal University Press, 2013), 23. ↩︎ - As support for the reasonableness of this rhyme, one may note that the sounds un and ün appear together in category 15. Xue Fan agrees that u and ü are near-rhymes, but at odds with me, he states that the category 5 and 7 i sounds are

near-rhymes as well. See note 17 above and Xue Fan, 《歌曲翻译探索与实践》

(Wuhan: Hubei Education Press, 2002), 100. Xue Fan’s aesthetic judgments carry

weight, as he is “China’s most renowned and prolific song translator.” See Lingli Xie, “Exploring the Intersection of Translation and Music: An Analysis of How Foreign Songs Reach Chinese Audiences” (Ph.D. diss., The University of Edinburgh, 2016), 61. ↩︎ - Duanmu, Syllable Structure, 95; 《诗韵新编》, 110, 113, 117–19, 122. ↩︎

- Chris Barker, “How Many Syllables Does English Have?”, unpublished

paper. An example of an English rhyming dictionary is Merriam-Webster’s Rhyming Dictionary (Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster, 2002). ↩︎ - Translators of Chinese poetry have specifically noted the paucity of rhyming resources in English. See Charles Kwong, “Translating Classical Chinese Poetry into Rhymed English: A Linguistic-Aesthetic View,” TTR: traduction, terminologie, rédaction 22 (2009): 189–220, esp. 191–97. ↩︎

- Jian-Sheng Yang, “A Contrastive Study of Cohesion in English and Chinese,” International Journal of English Linguistics 4, no. 6 (2014): 118–23, esp. 121. ↩︎

- Qingshun He, “Translation of Repetitions in Text: A Systemic Functional Approach,” International Journal of English Linguistics 4, no. 5 (2014): 81–88, esp. 86. For the original quotation, see Francis Bacon, “Of Studies,” in Richard Whately, ed., Bacon’s Essays: With Annotations (London: John W. Parker and Son, 1860), 498–540, esp. 498. The journal article author identifies the cited translator as Dong Xu, but does not specify the source. ↩︎

- Cecile Chu-chin Sun, The Poetics of Repetition in English and Chinese Lyric Poetry (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011), 63–83. ↩︎

- John M. Howie, “On the Domain of Tone in Mandarin,” Phonetica 30 (1974): 129–48, esp. 147. Howie’s research specifies that the tone modifies the pitch of the rhyming part of a syllable’s vowel. Incidentally, tone is common in languages other than the many dialects of Chinese; an estimated 60–70% of the world’s languages use lexical tone. See Moira Yip, Tone (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 1–4. ↩︎

- C. S. Champness, “What the Missionary Can Do for Church Music in China,” The Chinese Recorder and Missionary Journal 40 (1909): 189–94, esp. 190. The pentatonic nature of traditional Chinese music did not imply that the fourth and seventh notes of a major scale were unrecognizable as notes, but only that they were auxiliary tones infrequently heard in Chinese music. See Tran Van Khe, “Is the Pentatonic Universal? A Few Reflections on Pentatonism,” The World of Music

19 (1977): 76–84, esp. 81. The major pentatonic scale approximates the 宫 gōng

tuning of Chinese traditional music. See Ho Lu-Ting and Han Kuo-huang, “On

Chinese Scales and National Modes,” Asian Music 14 (1982): 132–54, esp. 133. ↩︎ - English: Baptist Hymnal (Nashville: Lifeway Worship, 2008), hymn #1; Mandarin: 《世紀頌讚 Century Praise》, bilingual edition (Hong Kong: Chinese Baptist Press, 2001), hymn #89; Southern Min: 《浸信會台語聖詩》 (Gaoxiong:

Gaoxiong Taiwanese Language Center, 1969), hymn #2. It is important to note that

the English text is itself a translation from German. See note 29 below. However, these Mandarin and Southern Min Chinese texts are most likely translations from English rather than German since they derive from Baptist hymnals. Chinese lyrics appear in the traditional Chinese characters used outside mainland China and Singapore. ↩︎ - The English rhyme scheme follows the German “original” set by Georg Strattner’s 1691 revision of Joachim Neander’s hymn. See Siegfried Fornaçon, “Lobe den Herren, den mächtigen König der Ehren,” Jahrbuch für Liturgik und Hymnologie 2 (1956): 130–33, esp. 132. ↩︎

- Huang Tian Ji, 《诗词创作发凡》 (Guangzhou: Guangdong People’s Press,

2003), 31. ↩︎ - Xu Zhi Gang, 《诗词韵律》 (Jinan: Jinan Press, 2002), 5. ↩︎

- Huang, 26–27. ↩︎

- Zhao Zhong Cai, 《诗词写作概论》 (Shanghai: Shanghai Ancient Texts Press, 2002), 33; Ove Lorentz, “The Conflicting Tone Patterns of Chinese Regulated

Verse,” Journal of Chinese Linguistics 8 (1980): 85–106, esp. 86–87. ↩︎ - As mentioned previously, 耶稣 yēsū “Jesus” and 基督 jīdū “Christ” rhyme in Modern Mandarin because they both end in the category 10 u sound. Their tonal

pronunciation also matches, in that these ending characters are both first tone. However, in earlier stages of the Chinese language they were not the same tone; 稣 was the high level tone, and 督 was the entering oblique tone. See 《诗韵新编》,

110, 122. It is possible that selection of Classical Chinese tones also shaped the

emotional nuances of poetry. See Kwong, “Translating Classical Chinese Poetry into Rhymed English,” 199n21. ↩︎ - Shui’er Han et al., “Co-Variation of Tonality in the Music and Speech of Different Cultures,” PLoS ONE 6, no. 5 (2011): 1–5, esp. 2. L1 English learners of Mandarin typically require training to broaden the range of their spoken pitch for accurate voicing of Mandarin tones. See Felicia Zhen Zhang, “The Teaching of Mandarin Prosody: A Somatically-Enhanced Approach for Second Language Learners” (Ph.D. diss., University of Canberra, 2006), 41–42. ↩︎

- L. H. Wee, “Unraveling the Relation between Mandarin Tones and Musical Melody,” Journal of Chinese Linguistics 35 (2007): 128–44, esp. 130–31. In Wee’s analysis, Mandarin tones 1 and 2 are “high” tones and tones 3 and 4 are “low” tones. Xue Fan proposes a more complicated ideal tone scheme in Xue, 160–61. ↩︎

- The tone numbers in the table above take into account the rules of Mandarin Chinese tone sandhi in order to reflect actual spoken tones rather than the tones of

individual syllables when voiced in isolation. For example, the final word 永远

yǒngyuǎn “forever” places two third tone syllables side by side, resulting in a

second tone-third tone pronunciation sequence due to sandhi. See Matthew Y. Chen, Tone Sandhi: Patterns across Chinese Dialects (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 20. ↩︎ - Murray Henry Schellenberg, “The Realization of Tone in Singing in Cantonese and Mandarin” (Ph.D. diss., The University of British Columbia, 2013), 139–41. Apparently, a lack of proper accounting for tone was a perceived defect in early missionary writing and translation of hymns in China. See Vernon Charter and Jean DeBernardi, “Towards a Chinese Christian Hymnody: Processes of Musical and Cultural Synthesis,” Asian Music 29 (1998): 83–113, esp. 91. ↩︎

- For example, one would expect 主 zhǔ “Lord” to appear in Christian song lyrics far more often than the identically sung 猪 zhū “pig.” When spoken there is a tone difference between the two zhu sounds. ↩︎

- Irene Ai-Ling Sun, “Songs of Canaan: Hymnody of the House-Church Christians in China,” Studia Liturgica 37 (2007): 98–116, esp. 104. ↩︎

- Lin Shiyao et al., eds.,《迦南詩選 1》(Taibei: Asian Outreach Ministries,

2001), hymn #9. ↩︎ - Connie Oi-Yan Wong, “Singing the Gospel Chinese Style: ‘Praise and Worship’ Music in the Asian Pacific” (Ph.D. diss., University of California, Los Angeles, 2006), 176–80. I can only speculate whether the melodies of Xiaomin’s

Canaan Hymns were a subconscious influence in writing 《神啊请荣耀祢的圣名》

(Song 4), which omits the third and seventh notes of the major scale as in Chinese traditional 商 shāng pentatonic tuning. See Ho and Han, “On Chinese Scales,” 133. ↩︎ - Wong, “Singing the Gospel Chinese Style,” 147–62. ↩︎

- Brian Cullen, “Exploring Second Language Creativity: Understanding and Helping L2 Songwriters” (Ph.D. diss., Leeds Metropolitan University, 2009), 332. ↩︎

- If he had witnessed my first Chinese Hebrew class, Confucius would have

been mortified that this student corrected my rendering of the Hebrew letter צ tsade, erroneously written backwards on the whiteboard. When I later realized that other students may have interpreted her action as improperly bold, I tried to shift the frame of reference from social behavior to attention to detail in language learning to affirm her without criticizing Chinese views on classroom etiquette. ↩︎ - A lyrics video with a recording of the seminary choir appears at https://vimeo.com/270937392. All of my Chinese worship songs appear on the channel page at https://vimeo.com/channels/1304157. At the time of submission of this article, there were 26 recorded hymns. ↩︎

- Henry S. Drinker, “On Translating Vocal Texts,” The Musical Quarterly 36 (1950): 225–40, esp. 235. ↩︎

- Charles W. Chapman, “Words, Music, and Translations,” The NATS Bulletin

34 (October 1977): 22–25, esp. 23. ↩︎ - Peter Low, “Singable Translations of Songs,” Perspectives: Studies in Translatology 11, no. 2 (2003): 87–103, esp. 92. ↩︎

- Eirlys E. Davies and Abdelâli Bentahila, “Translation and Code Switching in the Lyrics of Bilingual Popular Songs,” The Translator 14 (2008): 247–72, esp. 266. ↩︎

- Herbert F. Peyser, “Some Observations on Translation,” The Musical

Quarterly 8 (1922): 353–71, esp. 363. ↩︎ - I wish to extend my deepest thanks to Zhao Xizun for editing the lyrics of my first fifteen songs, as well as to Sun Jing (Songs 1–14) and Kevin Ng (Song 15) for bringing these Chinese worship songs to life through piano accompaniment.

Kevin Ng supplied the chords for《我要跟随祢 I Will Follow You》(Song 15). I am

grateful for the students of Baptist Theological Seminary, Singapore who “sing to

the LORD a new song” along with me. Lastly, I thank David Wilmington for prompting me to write this essay on my Chinese L2 songwriting experience. ↩︎