The Use of the Old Testament in the New Testament

Southwestern Journal of Theology

Volume 64, No. 1 – Fall 2021

Editor: David S. Dockery

There is no doubt that the OT was John’s primary source—other than his relationship with Jesus—in composing his Gospel (and to a lesser extent, his letters). When discussing John’s use of the OT, the first issue to be addressed is: Who is the author of these writings? There are not merely texts to be studied; rather, the texts we are called to interpret came into being because someone wrote them. And who that “someone” is matters, as it is that person who used the OT in certain ways. Texts do not use the OT; people—authors—do. These authors, in turn, use certain antecedent texts because of their personal experience, worldview, and theological presuppositions—which is why, after discussing the identity of the author of John’s Gospel and epistles, we will examine the distinctive outlook reflected in these writings. After this, we will trace the use of the OT by tracking with the Johannine narrative before closing our discussion with a brief look at the use of the OT in John’s letters (especially 1 John).

I. AUTHORSHIP

In examining the authorship of John’s Gospel, we will focus on the internal evidence, that is, claims pertaining to the author contained in the Gospel itself.1 In keeping with the narrative Gospel genre, there is no direct attribution to a person by name in the inspired text itself. We do, however, have the title “The Gospel according to John,” which is sufficiently early to count as evidence that there was widespread ancient belief that a person named John wrote the Gospel. The first question that arises, therefore, is this: Which person in the first century, attested in the NT writings, could simply be called “John” with the expectation that readers would easily be able to identify that person?2

1. Synoptics, Acts, and Paul. At least as far as the NT is concerned, the only prominent person other than John the apostle named “John” is the Baptist, but because of his untimely death he can immediately be ruled out as the author (Matt 14:1–12; Mark 6:14–29; cf. Luke 9:7–9; John 3:24). There is also John Mark, most commonly known simply as Mark, but as author of the second Gospel he, too, is at once disqualified.3 For these and other reasons, the only legitimate candidate emerging from the NT writings is John, the son of Zebedee. Indeed, this is the reason why the early fathers attributed the Gospel to the apostle.4 What, then, do we know about John from the other NT documents?

From the earlier three Gospels (the Synoptics), we know that John, the son of Zebedee, had a brother named James who was also a disciple of Jesus. Both James and John were among the twelve apostles of Jesus.5 Only Mark mentions the nickname “Boanerges,” which likely recalls the incident recorded in Luke 9:51–56 where Samaritans rejected Jesus’s messengers and James and John asked Jesus, “Lord, do you want us to call down fire from heaven to consume them?” (v. 54). Their fiery zeal, in turn, is reminiscent of Elijah and his contest with the prophets of Baal in OT times (1 Kgs 18:20–40). In apostolic lists, John is normally mentioned after James (with the exception of Acts 1:13, which may prepare for the pairing of Peter and John later on in the narrative), which suggests that he may have been the younger of the two.

According to the Synoptics, John was not only one of the Twelve but also one of a select group of three in Jesus’s inner circle, along with his brother James and the apostle Peter. They were the only ones who witnessed events such as the raising of the daughter of Jairus, the synagogue ruler (Matt 9:18–19, 23–26; Mark 5:21–24, 35–37; Luke 8:40–42, 49–50), the Transfiguration (Matt 17:2, Mark 9:2–3, Luke 9:28–36), and Jesus’s prayer in the Garden of Gethsemane the night before the crucifixion.6 Interestingly, none of these incidents is included in John’s Gospel. Instead, John features the raising of Lazarus (11:1–44); shows that Jesus’s glory was revealed in everything he said and did rather than merely at the Transfiguration (1:14; cf. 2:11); and focuses on Jesus’s glory rather than his suffering and agony (9:3; 11:4, 40).7 In addition, John would have witnessed the entire three-and-a-half-year ministry of Jesus and the vast majority of all the events and teachings recorded in the Synoptics.

Then, in the days of the early church following the crucifixion, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus, Peter and John are shown to be closely associated in ministry, such as when “going up to the temple for the time of prayer.”8 There, John witnessed Peter’s healing of an invalid at the Beautiful Gate and his public address at Solomon’s Portico. They were arrested that evening and put into custody overnight (3:3). We are told that, when people “observed the boldness of Peter and John and realized that they were uneducated and untrained men, they were amazed and recognized that they had been with Jesus” (4:13; cf. v. 19). Later in Acts, “[w]hen the apostles who were at Jerusalem heard that Samaria had received the word of God, they sent Peter and John to them,” who authenticated the reception of the Spirit by the Samaritans (8:14).

Later still, when writing to the Galatians, the apostle Paul recalls an occasion “[w]hen James [not the son of Zebedee], Cephas [Peter], and John—those recognized as pillars—acknowledged the grace that had been given to me, they gave the right hand of fellowship to me and Barnabas, agreeing that we should go to the Gentiles and they to the circumcised” (Gal 2:9). Here, we see that John was one of the “pillars” in the early church. There is also an indication that James, Peter, and John were to minister primarily to the Jews while Paul was to focus on the Gentiles.

This is some of the most important information we have about John, the son of Zebedee, from the Synoptic Gospels, Acts, and Paul. Most likely, all these documents had already been written when John penned his Gospel.

2. John’s Gospel. This, then, is the historical and literary context in which John wrote the Gospel. Interestingly, in verse 6 of John’s prologue, we read, “There was a man sent from God whose name was John.” The informed reader quickly discerns that the person referred to here is not the apostle but the Baptist. By identifying him merely as “John,” rather than as “John the Baptist [or Baptizer]),” the fourth evangelist makes clear that there will be another designation for John the apostle later in the Gospel, and this is exactly what we find. John the apostle’s call to discipleship may be referenced obliquely in 1:35–39. Beyond this, the Johannine narrative does not include a list of the names of the twelve apostles.9 One can reasonably assume that John, along with the other apostles, witnessed all of the events and teachings recorded in the first twelve chapters of John’s Gospel (including the seven signs of Jesus).10

Starting in chapter 13, however, a new literary character makes his appearance, the so-called “disciple Jesus loved” (13:23). This disciple is found first at Jesus’s side at the Last Supper and later in the high priest’s courtyard following Jesus’s arrest (18:15–16). He is also at the site of the crucifixion (19:35), the empty tomb (20:2, 8–9), and Jesus’s third and final resurrection appearance on the shore of the Sea of Galilee (21:7). Finally, Jesus converses with this disciple and Peter in the epilogue, discussing with them their respective callings (21:20–23).

After this, we are told that “[t]his is the disciple who testifies to these things and who wrote them down. We know that his testimony is true” (21:24). In this way, the author claims to be that “disciple Jesus loved” who was featured alongside Jesus in the Gospel at all the major junctures of his earthly ministry, especially during the final week of Jesus. Thus, the author is the “disciple Jesus loved,” and that disciple is one of the Twelve, as only the apostles were with Jesus at the Last Supper according to the Synoptics.11 All pieces of evidence gleaned from the NT writings point in the same direction: to the apostle John, the son of Zebedee, who was not only one of the Twelve, but even one of three in Jesus’s inner circle. In fact, as we will see below, John was closest to Jesus during his earthly ministry, closer than even the apostle Peter.

As to John’s relationship with Peter, we have already seen that in the apostolic lists, in events in which only the three in Jesus’s inner circle were included, and in the days of the early church, John is consistently paired with Peter.12 In keeping with this pattern, John’s Gospel features John and Peter jointly, especially during passion week. What is more, in each case it is John, “the disciple Jesus loved,” who is shown in a position superior to Peter’s and thus more ideally qualified to bear written witness. At the Last Supper, Peter asks the “disciple Jesus loved” regarding the identity of the betrayer (13:23–24); in the high priest’s courtyard, it is the beloved disciple who gains Peter access as he is acquainted with the high priest (18:15–16); both disciples run to the empty tomb together, yet the beloved disciple gets there first (20:2–9); at the Sea of Galilee, again it is the beloved disciple who first recognizes the risen Jesus, at which Peter jumps into the lake and swims toward Jesus (21:7); and in Jesus’s final conversation with these two disciples, he rebukes Peter and tells him to mind his own business when Peter questions him about the destiny of the beloved disciple (21:20–23).

While not in the sense of improper rivalry or competitive one-upmanship, the beloved disciple, as the author of the Gospel, stakes a claim to unmatched proximity to Jesus and thus presents himself as being in the perfect position to reveal who Jesus truly is.13 All of the above-adduced evidence converges to suggest that the author of the Gospel is the apostle John, the son of Zebedee. All of the information in the four Gospels, Acts, and Paul’s letters points to him. Conversely, there is no information in any of the biblical writings that points away from him. In our investigation of the use of the OT in John’s Gospel, we can therefore safely proceed on the assumption that we are investigating the apostle John’s use of the OT. This John, in turn, witnessed Jesus’s own use of the OT and was doubtless deeply impacted and influenced by him.14

II. JOHN’S WORLDVIEW

It is commonly recognized that one’s worldview profoundly affects the way a person approaches a given issue. John’s use of the OT is no exception; it, too, is governed by John’s overall outlook.15 At the most foundational level, John, as a Jew, would have believed in the existence of one, and only one, true God, as affirmed in the preeminent confession of Judaism, the Shema, enunciated in Deut 6:4: “Listen, Israel: The LORD our God, the LORD is one.” In addition, John would have affirmed that this God, YHWH, is both Creator of the universe and the one who had entered into a series of covenants with Israel. He redeemed the nation from Egyptian bondage at the exodus, gave the Israelites the law at Sinai, and later sent his Son to take up temporary residence on earth to manifest God’s presence (1:14, 18), to reveal his glory (2:11), and to die for the sins of his people (John 1:29, 36; 10:15, 17–18).

John, therefore, believed not only that Jesus is God’s agent in both creation and redemption, but also that Jesus is himself God, a notion that would have been deeply offensive to many of Jesus’s Jewish contemporaries because it seemed to violate Jewish monotheism.16 And yet, John affirms unequivocally that Jesus and God the Father are one (10:30). What is more, John believed that Jesus provided incontrovertible, tangible proof that he was the Messiah and Son of God (20:30–31). In his Gospel, he therefore sets forth seven selected messianic signs as evidence that Jesus fulfilled Jewish messianic expectations: He healed the sick (4:46–54; 5:1–15); opened the eyes of the blind (ch. 9); and even raised the dead (11:1–44).17 All these things were expected of the Messiah, and Jesus did them all.

John also believed in universal human sinfulness and affirmed that God’s wrath rests on unsaved humanity (3:19–21; 5:24). He believed in God’s future judgment (5:25–29) and claimed that the entire world languishes in moral darkness and must come to Jesus “the light” and believe in him for eternal life (1:4–5, 7–9; 8:12; 9:5; 11:9–10; 12:35–36, 47).18 John held that the world is currently ruled by Satan, “the ruler of this world” (12:31; 14:30; 16:11), and that the cross is at the center of a battle between God and Jesus on the one hand and Satan on the other;19 however, he does not view this battle as a struggle between two equally matched foes, but rather affirms that Jesus triumphed over Satan at the cross (e.g., 16:33; 17:4; 19:30).

While John saw the world in terms of polar opposites—light and darkness, life and death, flesh and spirit, above and below, truth and falsehood, love and hate, faith and unbelief—he does not affirm a static dualism.20 Rather, the Johannine mission motif shows that people can step out of darkness into the light; they can put their trust in Christ and be saved (e.g., 3:16; 5:24; 20:30–31).21 In terms of John’s eschatology, we see John accentuate the way believers can enjoy abundant spiritual life in Jesus already in the here and now (10:10) rather than having to await the eternal state.22 In this way, the simple distinction between the present age and the age to come is partially collapsed. Not only is Johannine eschatology inaugurated, in a very real sense it is realized in that it emphasizes believers’ present-day possession of salvation benefits. At the same time, a future element remains, including Jesus’s second coming and God’s final judgment (see esp. 5:25–29; cf. 21:22).

An essential element of John’s worldview is his use of Scripture.23 He believed in the authoritative nature of the Hebrew Scriptures and took important aspects of his theology and presentation of Jesus from antecedent texts, especially the Psalms, Isaiah, and, to a lesser extent, Zechariah. Even though this is not always acknowledged, John adopted a salvation-historical outlook toward God’s dealings with his people and related the coming and work of Jesus to previous figures and events, whether Abraham and Jacob, Moses and the exodus, and others. In addition, John believed that Jesus fulfilled Jewish institutions such as the temple or various Jewish festivals such as Passover or Tabernacles.24 In all these ways, John presented Jesus as the only way of salvation (14:6) and the fulfillment of Jewish hopes and aspirations.

III. JOHN’S USE OF SCRIPTURE IN THE GOSPEL

John’s Gospel starts out with a bang: An unmistakable allusion to the Genesis creation narrative.25 “In the beginning,” John writes, evoking reminiscences of the opening of the Hebrew Scriptures, but rather than continuing, “God created the heavens and the earth,” John writes, “was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God” (1:1). John’s affirmation of creation by God’s word was uncontroversial. His declaration that the Word was not only with God, but was itself God would have raised many eyebrows, however, as this raised the specter of ditheism—the belief in two gods—a belief that appeared to clash with the inviolable Jewish tenet of monotheism. Undaunted, John affirms Jesus’s deity at both ends of the prologue (1:1, 18) as well as at strategic junctures throughout the Gospel (5:18; 10:33; 19:7) and just prior to the concluding purpose statement (20:28). In fact, the declaration that Jesus and the Father are one comes at the very heart of the Gospel and climaxes the presentation of Jesus as God in the Festival Cycle (chs. 5–10).26

Gradually in the prologue, creation language gives way to exodus terminology. Thus, John affirms that the Word that (or who) was with God in the beginning took on flesh and made his dwelling among us (1:14).27 This solemn declaration of Jesus’s incarnation is followed by a reference to the giving of the law through Moses (1:17; cf. Exod 31:18; 34:28). The closing words of the prologue, “No one has ever seen God,” too, is reminiscent of Moses who asked to see God, but was told that no one can see God and live (1:18; cf. Exod 33:18, 20; 34:6). The prologue also includes repeated references to John the Baptist (1:6–8, 15), which prepare the reader for the beginning of the Johannine narrative in 1:19ff. In keeping with the portrayal of the Baptist in the earlier Gospels, he is depicted as the voice crying in the wilderness, “Make straight the way of the Lord,” in the words of the prophet Isaiah (1:23; cf. Isa 40:3).28 Isaiah will be John’s primary theological source in the remainder of the Gospel, not only regarding Jesus’s messianic signs and his “lifting up,” but also John’s sending Christology (cf. Isa 55:11).29

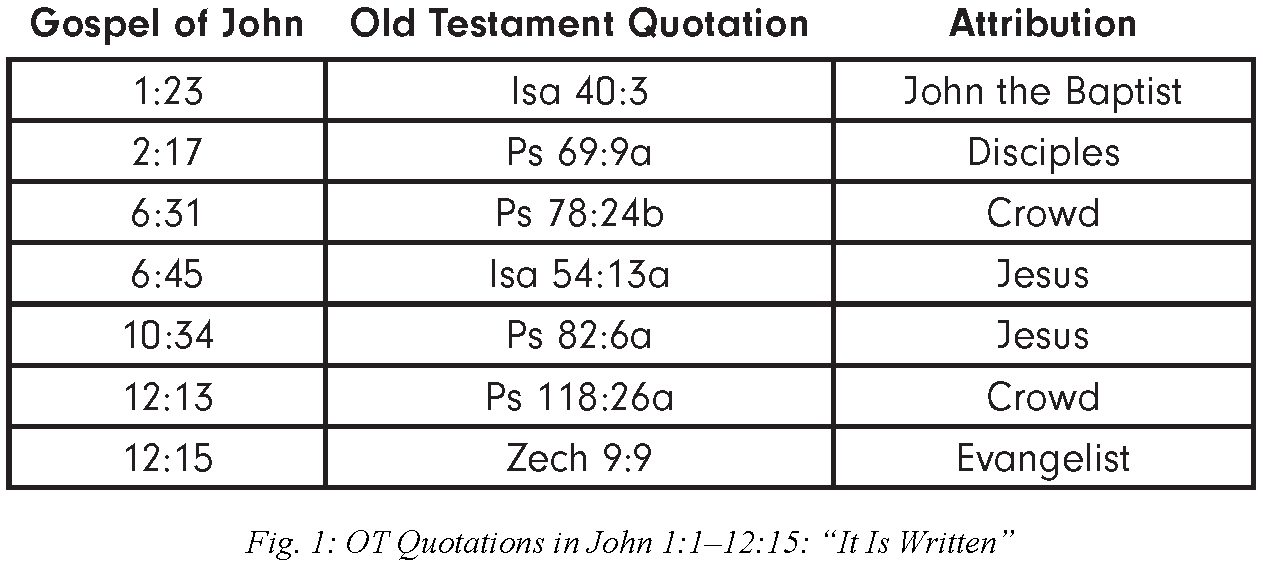

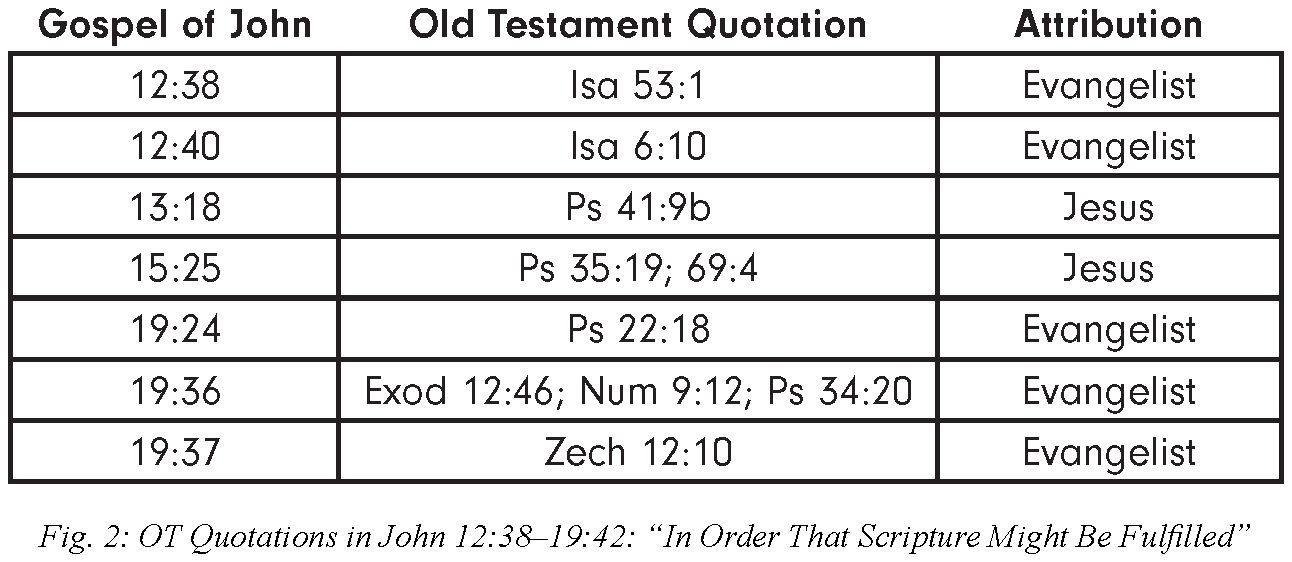

Explicit OT quotations in John’s Gospel follow a symmetrical pattern. In the first half of the Gospel, variations of the introductory formula, “It is written,” predominate; in the second half, starting at 12:38, John switches to fulfillment language.30 Each half contains seven quotations, for a total of fourteen for the entire Gospel. It is possible that John here employs numerical symbolism, as he is fond of the number “7” elsewhere. Both halves commence with a quote from Isaiah and conclude with a quote from Zechariah. Altogether, both sets of seven quotations include four references to the Psalms, two to Isaiah, and one to Zechariah (though 19:36 also includes a reference to Exodus and/or Numbers). In addition, John’s Gospel features numerous allusions and other scriptural symbolism.31 John strikes a note of scriptural fulfillment, especially with regard to Jewish obduracy (12:38, 40) and Jesus’s crucifixion (19:24, 36, 37). Fulfillment is also indicated by Jesus’s final cry, “It is finished” (19:30).32

1. Old Testament Quotations in Part 1 of John’s Gospel (1:1–12:15). As John makes clear toward the end of his Gospel, it is his avowed purpose to convince his readers that Jesus is the long-awaited Christ, the Son of God (20:30–31). Correspondingly, Philip identifies Jesus at the very outset as “him of whom Moses in the Law and also the prophets wrote” (1:45). Later in the Gospel, Jesus himself affirms that Moses wrote of him (5:46). When Jesus feeds the multitude, the crowd exclaims, “This truly is the Prophet who is to come into the world” (6:14; cf. Deut 18:15). When Jesus converses with Nathaniel, one of his early followers, he promises him that he “will see heaven opened and the angels of God ascending and descending on the Son of Man” (1:51), alluding to Jacob’s ladder in Gen 28:12.33 In chapter 4, reference is made both to Jacob’s field and well (4:5, 6; cf. v. 12). Thus, Jesus is shown to traverse patriarchal territory in the early stages of his ministry.34 The Moses/exodus connection is further reinforced by the Samaritan woman’s reference to “this mountain” (i.e., Mount Gerizim, 4:20; cf. Deut 27:12). This web of allusive references shows that John’s use of the OT cannot be fully gauged by explicit quotations; rather, John taps into whole chunks of OT narrative in telling Jesus’s story.35

Jesus’s first messianic sign of turning large quantities of water into wine unfolds against the backdrop of a wedding, which invokes the imagery of Jesus as groom, an impression that is reinforced soon thereafter when the Baptist calls himself “the groom’s friend” and identifies Jesus as the messianic bridegroom (3:29). At the temple cleansing, Jesus’s followers find his zeal for “my Father’s house” reminiscent of the psalmist’s depiction of one zealous for God and his “house” (i.e., the temple; 2:16–17; cf. Ps 69:20; see also Zech 14:21).36 Speaking to the “teacher of Israel,” Nicodemus, Jesus posits the necessity of a new birth (3:3, 5; cf. Ezek 36:25–27) and invokes the typology of Moses lifting up a bronze serpent in the wilderness. In the case of the latter, every Israelite who looked at the lifted-up serpent did not die of poisonous snakebites but survived; similarly, whoever would look at the crucified Christ would not perish but have eternal life (3:13–14; cf. Num 21:8–9). In addition to Moses/exodus typology, “lifted up” also conjures up the memory of the servant of the LORD in Isaiah (52:13; cf. 6:1).37 The evangelist’s reference to God giving “his one and only Son” (monogenēs; 3:16) is reminiscent of Abraham’s willingness to offer up his “only son” Isaac in Genesis 22.38

References to the Sabbath in the contrasting narratives featuring Jesus’s healings of the invalid in chapter 5 and the man born blind in chapter 9 (5:9; 9:14) again hark back to the creation narrative and reinforce the notion, already present in the earlier Gospels, that Jesus has authority over the Sabbath because he is the Creator (5:18–20; cf. Gen 2:1–3). Not only this, “just as the Father raises the dead and gives them life, so the Son also gives life to whom he wants…. For just as the Father has life in himself, so also he has granted to the Son to have life in himself” (John 5:21, 26). What is more, God has also given Jesus authority to execute the final judgment (5:27–28). In keeping with the Deuteronomic minimum requirement of two or three witnesses (Deut 17:6; 19:15; cf. John 8:17), Jesus adduces a series of witnesses to himself, ranging from John the Baptist (John 5:33–35) to Jesus’s works (v. 36), the Father himself (v. 37), and the Scriptures, and here particularly the writings of Moses (i.e., the Pentateuch; vv. 39, 45–47).

The feeding of the five thousand, another Johannine sign, continues the string of references to Moses and the exodus.39 The setting is Passover (6:4), which itself invokes the memory of God’s deliverance of the Israelites at the outset of the exodus. The feeding itself is reminiscent of Elisha’s similar feat (see esp. the mention of barley loaves, 6:9; cf. 2 Kgs 4:42). The crowd, though, take matters into a different direction and ask Jesus for a sign: “What sign, then, are you going to do …? Our ancestors ate the manna in the wilderness, just as it is written, ‘He gave them bread from heaven to eat’” (6:30–31; Ps 78:24). Just as Jesus had earlier furnished demonstration that he was greater than Jacob (4:12; cf. 1:51), he now asserts that he is greater than Moses: Not only does he give people bread to eat, he himself is the bread from heaven (6:35, 51); later, Jesus will assert superiority over Abraham as well (8:58; cf. v. 53). Embedded in the “bread of life discourse” is Jesus’s reference to the Prophets (i.e., Isaiah), “And they will all be taught by God” (6:45; cf. Isa 54:13), which implies that Jesus is God (or least God’s agent).

After a rather lengthy hiatus as far as explicit Scripture citations are concerned,40 John features another quote on the lips of Jesus in John 10:34: “Isn’t it written in your law, ‘I said, you are gods’?” In an argument from the lesser to the greater, he adds, “If he called those to whom the word of God came ‘gods’—and the Scripture cannot be broken—do you say, ‘You are blaspheming’ to the one the Father set apart and sent into the world, because I said: I am the Son of God?” (vv. 35–36; cf. Ps 82:6).41 The interchange follows Jesus’s bold assertion, “I and the Father are one” (10:30), at which the Jews attempt to stone him on account of blasphemy. Jesus here points out that the term “god” is applied in Scripture to people who are not necessarily divine, so calling himself “God” does not by itself merit capital punishment by stoning. The account of Jesus’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem features the last two OT quotes in the first half of John’s Gospel, citing Ps 118:26 and Zech 9:9, respectively (12:13, 15). The first quote is uttered by the crowd, the second furnished by the evangelist.42

2. Old Testament Quotations in Part 2 of John’s Gospel (12:38–19:42). Following a symmetrical pattern, as mentioned above, the second half of John’s Gospel, like the first, features seven OT quotations. The first two are by the evangelist; the next two by Jesus; and the last three (all in the passion narrative at Jesus’s crucifixion) again by the evangelist. Transitioning from the first to the second half of John’s Gospel, 12:38 serves as the pivot in John’s use of the OT, shifting from the introductory formula “it is written” (or a similar phrase) to “in order that Scripture might be fulfilled” (with slight variations). As in the first half of John’s Gospel, we find seven explicit OT quotations spanning from 12:38 (the closing of the Book of Signs) to 19:37 (the end of the Johannine passion narrative).

In 12:38 and 40, the evangelist quotes both Isa 53:1 and 6:10 to make his case that the Jews’ rejection of Jesus’s messianic signs was in keeping with scriptural prediction.43 The Jewish rejection of Jesus was not an accident; it was foretold by Isaiah and foreordained by God. While responsible for their sinful actions, the Jews “were unable to believe” due to divine hardening (v. 39). The mention of Isaiah seeing Jesus’s “glory” in verse 41 most likely refers to the prophet’s throne room vision recorded in Isaiah 6. In this way, the evangelist continues to assert Jesus’s preexistence. Just as he previously mentioned that Jesus was the preexistent Word (1:1), that he was before John the Baptist (1:15), and that “before Abraham was, I am” (8:58), he now affirms that Isaiah saw Jesus’s glory prior to his incarnation. This is part of John’s demonstration of the superiority of Jesus to antecedent figures in salvation history, including Abraham, Jacob, Moses, and others (cf. Heb 1:1).

The next two OT quotations are again found on Jesus’s lips. In both cases, Jesus affirms that people’s hatred of him was in fulfillment of scriptural expectation. In John 13:18, Jesus declares that Judas’s betrayal, arising from within the group of his closest followers, fulfilled Davidic typology in Ps 41:9: “The one who eats my bread has raised his heel against me.” Subsequently, in the Farewell Discourse, Jesus applies Ps 35:19; 69:4 to himself: “They hated me for no reason” (15:25).44 Thus, the first four OT quotations in the second half of John’s Gospel all focus on people’s rejection and hatred of Jesus and declare that this unprovoked and baseless animosity was in keeping with God’s sovereign plan.

The entire Farewell Discourse, for its part, parallels Moses’s farewell in Deuteronomy.45 Just like Moses prepared the Israelites for entering the promised land, so Jesus is shown to prepare his followers for the time following his crucifixion and resurrection. Jesus’s followers will no longer have his physical presence with them but instead enjoy the Spirit’s indwelling presence (14:18). While the evangelist called Israel “his own” at the outset of the Gospel (1:11), he now calls the Twelve Jesus’s “own” in the preamble to the passion narrative (13:1). Thus, the Twelve are the believing remnant, the new messianic community united in its belief in Jesus. This salvation-historical development is further reinforced by Jesus’s depiction of himself as the vine and his followers as branches on the vine, which is reminiscent of Isaiah’s Song of the Vineyard (15:1–10; cf. Isaiah 5).46

The final three OT citations are all found in the account of Jesus’s crucifixion.47 The soldiers’ actions fulfill the words of Ps 22:18, “They divided my clothes among themselves, and they cast lots for my clothing” (19:24). A set of Scripture passages, likely including Exod 12:46, Num 9:12, and Ps 34:20, is fulfilled when the soldiers decide not to break Jesus’s bones since he is already dead: “Not one of his bones will be broken” (19:36). Instead, one of the soldiers pierces Jesus’s side, fulfilling the words of Zechariah 12:10: “They will look at the one they pierced” (19:37).48 In addition, Jesus’s words on the cross, “I’m thirsty,” fulfill Ps 69:22. Thus, the evangelist sees in the events surrounding Jesus’s crucifixion the fulfillment of an entire matrix of scriptural expectations regarding the sacrificial death of the Messiah. This further reinforces the notion that Jesus’s death on the cross was divinely and sovereignly orchestrated, human rejection and supernatural opposition notwithstanding.

IV. JOHN’S USE OF THE OLD TESTAMENT IN HIS LETTERS

While, as we have seen, John uses the OT extensively in his Gospel, the same cannot be said for his letters. Apart from a passing reference to Cain, “who was of the evil one and murdered his brother … [b]ecause his deeds were evil, and his brother’s were righteous” (1 John 3:12), anyone searching for explicit OT quotations or even allusions will come up virtually empty-handed. A possible exception is the reference just prior to the above quoted reference to Cain, namely John’s declaration that “[e]veryone who has been born of God does not [persist in] sin, because his seed remains in him” (1 John 3:9). While not all commentators would agree, a good case can be made that the reference to God’s seed here is to the Holy Spirit, and that “seed” (sperma) harks back to the reference to the woman’s “offspring” in the proto-evangelion of Gen 3:15.49 While in John 8:31–47 Jesus spars with his opponents as to their true spiritual parentage, here John takes the biblical trajectory regarding offspring a step further by identifying the Holy Spirit as the seed that causes the new birth in believers. Otherwise, John’s first letter is concerned primarily with reassuring readers in view of the recent departure of individuals who apparently claimed special spiritual status while ignoring their sinfulness and need for atonement (1 John 2:19; cf. 1:9, 10; 2:2). Likely written after the Gospel, John’s first letter seeks to reestablish and defend the premise of the Gospel: that Jesus is the Messiah and Son of God (e.g., 1 John 4:2–3; cf. John 20:30–31; 2 John 7). Second and 3 John deal with the issue of extending hospitality to itinerant teachers.

V. CONCLUSION

The apostle John, the son of Zebedee, was the closest person to Jesus during his earthly ministry. A half-century after Jesus’s time on earth, John likely penned first the Gospel, and then three letters. In his Gospel, John tied the story of Jesus closely to the metanarrative told in the Hebrew Scriptures. In so doing, John connected Jesus with the Genesis creation narrative, the exodus narrative, and OT prophetic literature, especially Isaiah, but also Zechariah. In addition, he drew rather extensively on prophetic passages found in the Psalms. John’s primary purpose in using the OT in his Gospel is the demonstration that Jesus is the Messiah and Son of God by showcasing seven selected signs of Jesus. These signs were designed to elicit faith in John’s readers that Jesus’s claims were true. To this day, John asks of us the probing question: Will you believe in Jesus? Those who do, John affirms, have the right to become children of God and will not perish but have eternal life.

- What is said here about the author of John’s Gospel derivatively also applies to the author of John’s letters due to the stylistic affinity between these writings. For in-depth discussions of introductory matters for John’s Gospel and letters, see Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum, and Charles L. Quarles, The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament, 2nd ed. (Nashville: B&H Academic, 2016), chs. 7 and 19. For a more popular, but still fairly thorough, treatment, see Andreas J. Köstenberger, Signs of the Messiah: An Introduction to John’s Gospel (Bellingham, WA: Lexham, 2021), ch. 1. ↩︎

- A contemporary analogy might be Portuguese or Brazilian soccer players being identified simply by their first names, such as “Ronaldo” or “Fred.” ↩︎

- Cf. Acts 12:12 (“John who was called Mark”), 25 (“John who was called Mark”); 13:5 (“John”), 13 (“John”); 15:37 (“John who was called Mark”), 39 (“Mark”). ↩︎

- See, e.g., Irenaeus, Heresies 3.1.2: “John the disciple of the Lord, who leaned back on his breast, published the Gospel while he was a resident at Ephesus in Asia” (note the allusion to John 13:23; cf. 21:20). ↩︎

- Matt 10:2: “James the son of Zebedee, and John his brother”; Mark 3:17: “to James the son of Zebedee, and to his brother John, he gave the name ‘Boanerges’ (that is, ‘Sons of Thunder’)”; Luke 6:14: “James and John”; Acts 1:13: “Peter, John, James, Andrew.” Interestingly, there is no such apostolic list in John’s Gospel. ↩︎

- Matt 26:36–56, v. 37: “Peter and the two sons of Zebedee”; Mark 14:32–42, v. 33: “Peter, James, and John”; cf. Luke 22:39–46. ↩︎

- For a discussion of John’s theology of the cross, see Andreas J. Köstenberger, A Theology of John’s Gospel and Letters: The Word, the Christ, the Son of God, BTNT (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2009), ch. 14. ↩︎

- I.e., at 3 o’clock in the afternoon; 3:1, 3, 4, 11. ↩︎

- The Twelve are mentioned, almost in passing, at 6:67, 70, 71, and 20:24. ↩︎

- See Andreas J. Köstenberger, “The Seventh Johannine Sign: A Study in John’s Christology,” BBR 5 (1995): 87–103. ↩︎

- Cf. Matt 26:20: “the Twelve”; Mark 14:17, 20: “the Twelve”; Luke 22:14: “the apostles”; note that Jesus had sent “Peter and John” to prepare the Passover (Luke 22:8). ↩︎

- Both, along with their brothers, were Galilean fishermen: see Matt 4:18–22; Mark 1:16–20. The parallel in Luke 5:1–11 only refers to Peter, called “Simon.” Interestingly, John 1:35–42 makes no reference to Peter and Andrew’s vocation as fishermen. ↩︎

- See also the connection between 1:18 and 13:23, both of which refer to a person being at another person’s “side,” with attendant qualification to reveal that person’s unique identity. See Köstenberger, Signs of the Messiah, 16–17. On the alleged rivalry between “the beloved disciple” and Peter in John’s Gospel, see Andreas J. Köstenberger, The Missions of Jesus and the Disciples according to the Fourth Gospel (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998), 154–61. ↩︎

- See, e.g., John Wenham, Christ and the Bible, 3rd ed. (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1994; repr. Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2009), esp. ch. 5. See also R. T. France, Jesus and the Old Testament: His Application of Old Testament Passages to Himself and His Mission (Downers Grove: IVP, 1971; repr. Vancouver, BC: Regent College, 2000). ↩︎

- For a thorough discussion of John’s worldview, see Köstenberger, Theology of John’s Gospel and Letters, ch. 6. ↩︎

- See Andreas J. Köstenberger and Scott R. Swain, Father, Son and Spirit: The Trinity and John’s Gospel, NSBT 24 (Downers Grove: IVP, 2008), ch. 1. ↩︎

- See Köstenberger, Signs of the Messiah. ↩︎

- On life and light in John’s Gospel, see Köstenberger, Theology of John’s Gospel and Letters, 341–49. ↩︎

- Cf., e.g., John 13:27: “After Judas ate the piece of bread, Satan entered him.” ↩︎

- Köstenberger, Theology of John’s Gospel and Letters, 277–92. ↩︎

- On the Johannine mission theme, see Köstenberger, Theology of John’s Gospel and Letters, ch. 15; Köstenberger, The Missions of Jesus and the Disciples. ↩︎

- On Johannine eschatology, see Köstenberger, Theology of John’s Gospel and Letters, 295–98. ↩︎

- See Köstenberger, Theology of John’s Gospel and Letters, 298–310. ↩︎

- Temple: 2:18–21; 4:21–24; Passover: 13:1; 19:36; Tabernacles: chs. 7–8; Dedication: 10:22. On Jesus’s fulfillment of festal symbolism, see Köstenberger, Theology of John’s Gospel and Letters, ch. On Tabernacles, see also Köstenberger, “John,” 451–59. ↩︎

- Due to space constraints, the following discussion can only cover some of the highlights in John’s use of Scripture. For much more detail, see Andreas J. Köstenberger, “John,” in Commentary on the New Testament Use of the Old Testament, eds. G. K. Beale and D. A. Carson (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2007), 415–512. On the creation theme in John’s Gospel, see Köstenberger, Theology of John’s Gospel and Letters, ch. 8. ↩︎

- See Köstenberger, Signs of the Messiah, 73–75. ↩︎

- The Greek word is skēnoō, “tabernacle.” ↩︎

- Cf. Matt 3:3; Mark 1:3; Luke 3:4–6. See Köstenberger, “John,” 425–28. ↩︎

- Andreas J. Köstenberger “John’s Appropriation of Isaiah’s Signs Theology: Implications for the Structure of John’s Gospel,” Themelios 43, no. 3 (2018): 376–86; Catrin H. Williams, “Isaiah in John’s Gospel,” in Isaiah in the New Testament, eds. Steve Moyise and Maarten J. J. Menken, The NT and the Scriptures of Israel (London: T&T Clark, 2005), 101–16. ↩︎

- See Figures 1 and 2 on pages 50 and 53. Except for 1:23 (ephē) and 12:13, all Scripture quotations in part 1 are introduced by a formula that includes graphē (“Scripture”) or gegrammenon (“written”); all Scripture quotations in part 2 include plērōthē (“might be fulfilled”; 19:36 and 37 is a joint quotation). See Köstenberger, “John,” 416. ↩︎

- See the list of OT allusions and verbal parallels in John’s Gospel in Köstenberger, “John,” 419–See also D. A. Carson, “John and the Johannine Epistles,” in It Is Written: Scripture Citing Scripture: Essays in Honour of Barnabas Lindars, SSF, eds. D. A. Carson and H. G. M. Williamson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 251–53. ↩︎

- See Figure 1 on page 50. Note that there is considerable variety as to who supplies the citation. Most (though not all) quotations conform fairly closely to the Septuagint (LXX), though some are independent. See Köstenberger, “John,” 417–18 (esp. chart on p. 417). ↩︎

- Cf. Köstenberger, “John,” 429–30. ↩︎

- Catrin H. Williams, “Patriarchs and Prophets Remembered: Framing Israel’s Past in the Gospel of John,” in Abiding Words: The Use of Scripture in the Gospel of John, eds. Alicia D. Myers and Bruce G. Schuchard, RBS 81 (Atlanta: SBL, 2015), 187–212. ↩︎

- See on this Richard B. Hays, Echoes of Scripture in the Gospels (Waco: Baylor University Press, 2016), ch. 4. On Moses, see John Lierman, “The Mosaic Pattern of John’s Christology,” in Challenging Perspectives in the Gospel of John, ed. John Lierman, WUNT 2/219 (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2006), 210–34. ↩︎

- Köstenberger, “John,” 431–34. ↩︎

- See also John 8:28 and 12:32; Köstenberger, “John,” 436–37. ↩︎

- See esp. v. 2: “Take your son, your only son Isaac, whom you love…” On monogenēs, see Köstenberger, “John,” 422–23. ↩︎

- Andreas J. Köstenberger, “The Exodus in John,” in The Exodus in the New Testament, ed. Seth M.

Ehorn (London: T&T Clark, forthcoming). On the use of the OT in John 6, esp. vv. 31 and 45,

see Köstenberger, “John,” 443–51. ↩︎ - Though note that the “good shepherd” discourse in chapter 10 is predicated upon Ezekiel’s indictment of Israel’s “faithless shepherds” in Ezekiel 34. See also Jesus’s allusion to Ezekiel’s prophecy regarding a time when there would be “one flock, one shepherd” (10:16; cf. Ezek 34:23). On Ezekiel’s influence on John’s Gospel, see Gary T. Manning, Echoes of a Prophet: The Use of Ezekiel in the Gospel of John and in Literature of the Second Temple Period (London: T&T Clark, 2004); Brian Neil Peterson, John’s Use of Ezekiel: Understanding the Unique Perspective of the Fourth Gospel (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2015). ↩︎

- Köstenberger, “John,” 464–67. ↩︎

- Köstenberger, “John,” 470–74. ↩︎

- Daniel J. Brendsel, “Isaiah Saw His Glory: The Use of Isaiah 52–53 in John 12,” BZNW 208 (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2014); Köstenberger, “John,” 477–83. ↩︎

- On 13:18, see Köstenberger, “John,” 485–87; on 15:25, see also Köstenberger, “John,” 493–95. ↩︎

- John W. Pryor, John: Evangelist of the Covenant People (Downers Grove: IVP, 1992), 216, n. 8, notes the similarity between the language used in 14:15–24 (“know,” “love,” “obey,” “see”) and language used in Exodus 33–34 and Deuteronomy. ↩︎

- On Johannine ecclesiology, see Köstenberger, Theology of John’s Gospel and Letters, ch. 12. ↩︎

- On the use of the OT in the Johannine passion narrative, see Köstenberger, “John,” 499–506. ↩︎

- Remarkably, in the original instance, the one pierced is YHWH; in the present case, it is Jesus. See Köstenberger, “John,” 504–6. ↩︎

- See Andreas J. Köstenberger, “The Cosmic Drama and the Seed of the Serpent: An Exploration of the Connection between Gen 3:15 and Johannine Theology,” in The Seed of Promise: The Sufferings and Glory of the Messiah. Essays in Honor of T. Desmond Alexander, eds. Paul Williamson and Rita Cefalu (Wilmore, KY: GlossaHouse, 2020), 265–85. ↩︎