Southwestern Journal of Theology (48.1)

Southwestern Journal of Theology

Volume 48, No. 1 - Fall 2005

Editor: Paige Patterson

New Testament textual criticism is the discipline concerned with the transmission of the New Testament text and the attempt to reconstruct the original text.1 After the original New Testament documents were penned, they were passed from one group of believers to another. Along the way, believers made copies because the documents were important for the life of the church. The process of copying was painstaking, as each document was copied by hand, one letter at a time. During this process of copying, scribes occasionally made mistakes and introduced errors into the manuscript tradition.

Since the original documents no longer exist, one who wishes to know how the original text read must reconstruct it by comparing the manuscripts which have survived, deciding which of the variant readings is most likely original. This has been the traditional goal of New Testament textual criticism, although some now argue that this goal is unreachable. It is more important, they suggest, to understand the function of the manuscripts in the life of the church through the ages.2 Critics are right to identify the importance of the manuscripts in the life of the church, but the task of reconstruction remains important even for those who study the New Testament only as a literary document. How much more so for those who believe that God communicated an inspired and inerrant word through the original documents!

Bart Ehrman is an influential New Testament scholar who has written extensively in textual criticism. Now coauthor with Bruce Metzger of The Text of the New Testament, one of the standard academic introductions to textual criticism, Ehrman is most widely recognized for his recent book Misquoting Jesus, which is designed as a popular introduction to textual criticism.3 His more extensive individual work on the transmission of the New Testament text is The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture.4 In both Misquoting Jesus and The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture, Ehrman argues that scribes sometimes intentionally changed the sacred texts that they were copying.

As one may infer from the latter book’s title, Ehrman identifies these changes as corruptions. Although he claims to use the term in a neutral sense comparable to emendation, he has been rightly criticized for the title’s polemical tone.5 The implication of the title is that the New Testament itself is corrupt and therefore an unreliable guide for faith and life. In fact, the end result of Ehrman’s study of the New Testament text was a departure from evangelical faith, the details of which he recounts in Misquoting Jesus.6 Whereas he has been rightly criticized for the polemical tone of The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture, he has been rightly praised for the interdisciplinary nature of the work, since he demonstrates how New Testament textual criticism impacts the study of church history and historical theology.7

Moreover, the implications of Ehrman’s study reach far beyond these areas, particularly given the recent publication of Misquoting Jesus. There is a fair chance that someone in the average congregation has heard the claim that scribes intentionally changed the New Testament text. There is a better than average chance that students on college campuses will run across Ehrman’s claims. Thus, given Ehrman’s work, the pastor, Sunday school teacher, student minister, and evangelist, not to mention the apologist and theologian, may soon face questions regarding the authenticity and legitimacy of the New Testament text.

In what follows, I provide a sample of the way in which one may evaluate a textual variant. The primary text under consideration is Mark 1:1, but a brief moment will be spent dealing with Ehrman’s discussion of Luke 3:22 since it has implications for Mark 1:1. In the evaluation of the text, I will give particular attention to Ehrman’s claim that the variant represents an orthodox corruption of scripture.

One further note may prove helpful before moving ahead. After reflecting time and time again upon Ehrman’s discussion of Luke 3:22 and Mark 1:1, as well as his work as a whole, I suspect that his description of the polemical climate of the first few centuries provides a clue to his own methodology. Ehrman adopts Bauer’s argument that “orthodoxy” as such did not exist during the second and third centuries. Instead, there were a variety of competing views, only one of which eventually emerged as “orthodoxy” as a result of social and historical forces. It was only when this party won the day that its beliefs were said to represent the church at large.8

The polemical context, Ehrman argues, affected the way in which Christians handled the text. “Mistakes” were often intentional alterations used to make texts “more orthodox on the one hand and less susceptible to heretical construal on the other.”9 Christians forged documents in the names of their opponents and even attacked the character of their opponents. While they often accused their opponents of doing these things, it was most often the Christians who did not play fair.10

I suspect that the goal of Ehrman’s discussion is not to provide a detailed examination of all of the evidence, but to win, to persuade, and to influence. In attempting to do so, he at times exaggerates, mischaracterizes, and omits evidence.11 In addition, by frequent repetition, he makes his arguments appear stronger than they really are. In a way, Ehrman comes across as a politician. We may expect politicians to repeat themselves, to exaggerate, to mischaracterize and omit evidence, but we do not expect scholars to do so.12

Luke 3:22

Simply put, Ehrman’s thesis is that “scribes occasionally altered the words of their sacred texts to make them more patently orthodox and to prevent their misuse by Christians who espoused aberrant views.”13 The alterations, which he labels “corruptions,” were not primarily intended to change the beliefs of opponents but to bolster the claims of the orthodox party. Ehrman consistently claims that the changes were made in order to communicate more clearly what the texts were already known to mean.

By examining these corruptions, Ehrman believes that one can discern something of the hermeneutical intentions of the scribes and the resulting function of the new texts, since scribes were in essence interpreting texts as they copied them.14 Quite often, Ehrman argues, a scribe corrupted the text which contemporary critics commonly accept as original. That is, the “orthodox corruption” stands only as a variant and is clearly not the original text. In some instances, however, Ehrman argues that a corrupted text is the one commonly accepted as original, and that the original text is actually one with possible heretical implications.

Such is the case in his discussion of the baptism of Jesus as recorded in Luke 3:22. The issue concerns the language of the divine speech. According to Luke, did the Father declare, “You are my beloved Son, in you I am well pleased,” or, in a citation of Ps. 2:7, “You are my Son, today I have begotten you”? Ehrman not only argues that the text with possible adoptionistic implications is original, but also interprets the text in an adoptionistic—or, to transform one of his terms, a proto—adoptionistic manner—claiming that Jesus became the Son of God at his baptism. After presenting the evidence for his preferred text, Ehrman writes:

Together, these texts presuppose that at the baptism God actually did something to Jesus. This something is sometimes described as an act of anointing, sometimes as an election. In either case, the action of God is taken to signify his ‘making’ Jesus the Christ. These texts, therefore, show that Luke did not conceive of the baptism as the point at which Jesus was simply ‘declared’ or ‘identified’ or ‘affirmed’ to be the Son of God. The baptism was the point at which Jesus was anointed as the Christ, chosen to be the Son of God.15

Ehrman’s conclusion regarding Luke 3:22 points to the interpretive lens that he will apply to his discussion of other texts which he identifies as corrupt.

Ehrman’s preferred text has, however, an inferior date in the Greek manuscript tradition. While it is true that manuscript evidence must be weighed rather than counted, Ehrman’s preferred reading appears in only one Greek manuscript, whereas the other reading has support in a number of Greek manuscripts and appears in every text type. In fact, Ehrman himself notes that his preferred reading virtually disappears from sight. Whereas he uses this as evidence for an orthodox corruption, it seems highly unlikely that an original reading would be almost completely wiped out from the Greek manuscript tradition. In order for this to happen, it would have required not just one scribe to have made a change for theological reasons, but an entire series of scribes to have uniformly and intentionally eradicated evidence of the original reading. This represents much more of a conspiracy than either Ehrman himself argues for or logic warrants.

A full discussion of the Luke text must wait for another day, but Ehrman’s conclusions regarding Luke 3:22 set the tone for his discussion of Mark 1:1.16 Although the implications are not as obvious as those in his discussion of Luke 3:22, Ehrman gives cause for concern through his assumptions regarding the adoption of Jesus.

Mark 1:1

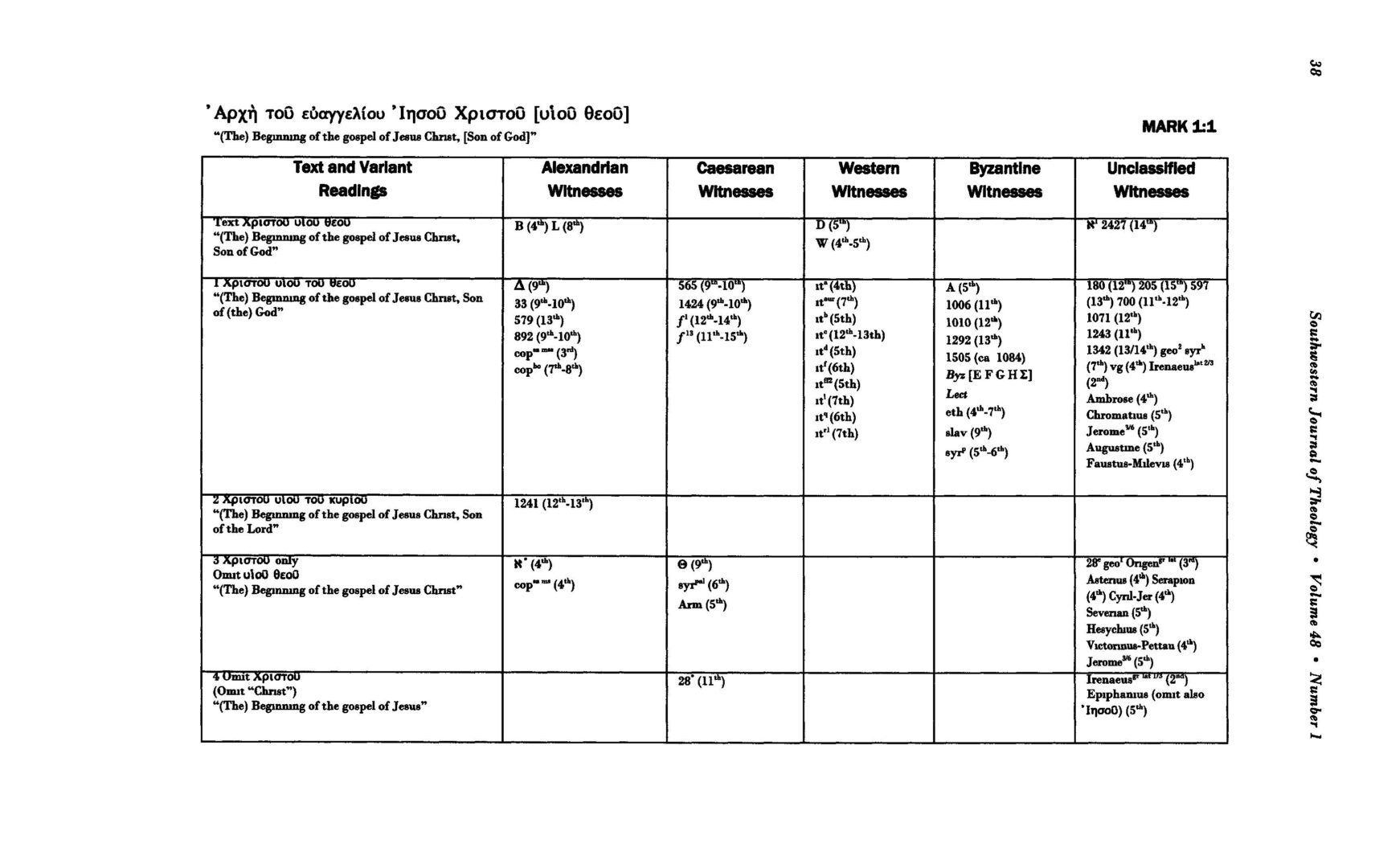

In the fourth edition of the United Bible Societies’ Greek New Testament, Mark 1:1 reads: Ἀρχὴ τοῦ εὐαγγελίου Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ Υἱοῦ [υἱοῦ θεοῦ] – “(The) Beginning of the gospel of Jesus Christ, [Son of God].” The editors placed υἱοῦ θεοῦ (Son of God) in brackets because of the significant difficulty in ascertaining whether or not it was original.17 In addition to this reading, which I will identify as “the text,” the editors include four variant readings. As evidenced from the chart below, two readings include υἱοῦ θεοῦ, the reading listed in the text and variant 1, which adds the article before θεοῦ. Variant 2 replaces θεοῦ with κυρίου. Variant 3, Ehrman’s preferred reading, omits υἱοῦ θεοῦ so that the verse ends at Χριστοῦ. Variant 4 combines the omission of υἱοῦ θεοῦ in 28* and some readings from Irenaeus with the further omission of Ἰησοῦ in a reading from Epiphanius. In the discussion which follows, variant 2 can be safely dismissed because of its exceedingly minimal and late attestation. Since the question at hand is really whether the original text of Mark 1:1 included υἱοῦ θεοῦ, the reading in the text and variant 1 may be grouped together while variants 3 and 4 may be grouped together.18

In evaluating Mark 1:1, I seek to determine the reading most likely to be original, thereby attempting to discern if the inclusion of “Son of God” represents an anti—adoptionistic corruption of scripture. While there are a variety of methodological approaches to textual criticism, I adopt an approach (known as “reasoned eclecticism”) which attempts to balance both external and internal evidence.19 External evidence includes the date, geographical distribution, and genealogical relationship of the readings. The evaluation of internal evidence includes the examination of transcriptional probabilities, intrinsic probabilities, the length of readings, the similarity of readings to parallel texts, the difficulty of readings, and the reading which best explains the origin of other readings.

As for the date of a reading, the earlier the reading is found, the more likely it is to be original. A reading with wide geographical distribution should be preferred over one without such diversity. Genealogical relationship refers to the broad families associated with particular manuscripts. Texts which demonstrate similar tendencies are grouped together in a family or text type. A reading found only in one text type should not be regarded as highly as a reading found in multiple text types. Furthermore, according to most approaches, readings of the Alexandrian type are the most highly preferred, whereas readings of the Byzantine type are the most highly questionable.

In evaluating transcriptional probabilities, one considers scribal habits and practices to determine what may have occurred in the transmission of the text. In evaluating intrinsic probabilities, one examines how a reading fits within the thought and argument of a passage or book. As for length, the shorter reading is preferred because scribes would more likely add to a text than take part of it away. A reading different from a parallel should be preferred because of the tendency among scribes to harmonize passages. The more difficult reading should be preferred because scribes would more likely change a difficult text than make a simple text difficult. Finally, a reading should be preferred if it best explains the origin of other readings. By applying each of these principles, I attempt to base the textual decision upon the composite picture which the totality of the evidence presents.

I also examine the following claims which Ehrman makes regarding the omission of “Son of God” in a portion of the manuscript tradition:

- “In terms of antiquity and character, this [the manuscripts which omit υἱοῦ θεοῦ] is not a confluence of witnesses to be trifled with.”20

- “Two of the three best Alexandrian witnesses of Mark support this text [which omits υἱοῦ θεοῦ].”21

- “This slate of witnesses [i.e., manuscripts which omit υιού θεού] is diverse both in terms of textual consanguinity and geography.”22

- The omission of υἱοῦ θεοῦ occurs in “such a wide spread of the tradition” that it cannot be accidental.23

- “Since the omission [of υἱοῦ θεοῦ] occurs at the beginning of a book, it is unlikely to be accidental.”24

- “Mark does not state explicitly what he means by calling Jesus the ‘Son of God,’ nor does he indicate when this status was conferred upon him.”25

- “The shorter text appears in relatively early, unrelated, and widespread witnesses.”26

Among these seven statements, we find Ehrman repeating himself in different ways several times. By doing so, his argument appears stronger than it really is. More importantly, it is not enough for a reading simply to be relatively diverse, widespread, or early. Instead, we seek to find the reading that is the most diverse, the most widespread, and the earliest. In addition, we must choose the reading that best answers the questions raised by examining the internal evidence. Finally, as we consider the claim that the text represents an anti—adoptionistic corruption, we must ask whether Ehrman has truly built a case that this is so or has instead simply raised the possibility.

External Evidence

Date

None of the readings has support from the early papyri. The readings show up in Greek manuscripts beginning in the fourth century, with the short reading (variant 3) enjoying the support of the first hand of א (the first corrector of א changed the reading to υἱοῦ θεοῦ, but it is not possible to know the time of the correction). Apart from א, which is of course significant, the short reading occurs only in two other Greek manuscripts, the corrector of 28 and also Θ, which dates from the ninth century. The inclusion of υἱοῦ θεοῦ finds support in B, a fourth—century manuscript, W, a fourth— or fifth—century manuscript, as well as the Greek manuscripts A and D, both from the fifth century.

The versional evidence in large part supports the inclusion of υἱοῦ θεοῦ. The Coptic (Sahidic dialect, fourth century) exhibits a divided tradition, with one manuscript supporting the omission and the rest supporting the inclusion of υἱοῦ θεοῦ. The Palestinian Syriac (sixth century) and the Armenian (fifth century) versions also omit υἱοῦ θεοῦ, whereas the inclusion finds support in the Latin tradition, beginning in the fourth century, the Ethiopie tradition from the fourth to seventh centuries, and the Syriac Peshitta from the fifth to sixth centuries. The evidence from the Fathers is divided. As early as the second century, Irenaeus notes both readings. Both readings then find further support in the fourth and fifth centuries. Based upon the evidence, the date of the readings cannot by itself decide the issue.

Geographical Distribution

Variant 1 exhibits the most diverse geographical distribution with support from Egypt, Italy, Palestine, North Africa, as well as areas near modern Ethiopia, the Baltics, and Georgia. Variant 3 has the next best geographical distribution with attestation in Egypt, Italy, and Palestine. The text, variant 2, and variant 4 exhibit localized readings. Given the manner in which we are approaching the variants—namely, those which include “Son of God” compared to those which do not—the inclusion enjoys better geographical distribution.27 So, while Ehrman is correct that his preferred reading is widespread, it is not the most widespread.

Genealogical Relationship

The inclusion of υἱοῦ θεοῦ finds support in all four text types, with a significant number of manuscripts of the Alexandrian tradition. Although Ehrman claims that the witnesses for the omission are diverse “both in terms of textual consanguinity and geography,” the evidence simply does not line up with the claim.28 The omission has support only in the Alexandrian and Caesarean traditions, along with several unclassified witnesses. And, while the text-critical principle that manuscripts should be weighed rather than counted holds true, the reading does appear in a very limited number of Greek manuscripts. Ehrman notes this limited number, but suggests that the manuscripts without the reading are noteworthy and include two of the three best Alexandrian witnesses for Mark.29 This suggestion is puzzling, since the only Alexandrian Greek manuscript which includes the reading is [א].30 If he intends to identify the Coptic Sahidic, then this suggestion carries little weight since one manuscript supports the omission whereas the remainder of the tradition supports υἱοῦ τοῦ θεοῦ. Given the evidence, the inclusion of υἱοῦ θεοῦ has better support.31

Internal Evidence

Transcriptional Probabilities

Three possibilities exist regarding the transcription of Mark 1:1. The most popular position suggests that the original text contained υἱοῦ θεοῦ and that a scribe accidentally omitted the title due to homoio-teleuton (similar ending).32 When this type of error occurs, a scribe’s eye skips from one word to another because of the similar endings. An error of this sort is particularly probable in Mark 1:1 due to the long series of genitives and the almost certain use of nomina sacra, common abbreviations for divine names. Using nomina sacra, the phrase Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ υἱοῦ θεοῦ would become ΙΥΧΥΥΥΘΥ. Each pair of letters would normally include a horizontal stroke above them to indicate the abbreviation. It is easy to see how, after recording IYXY, a scribe’s eye could have accidentally skipped from the final upsilon in Χ Y to the final upsilon in ΘΥ, continuing on with the next words after failing to record YYΘΥ.33

The lines of text below include Mark 1:1 along with the beginning of verse 2. Manuscripts were written in continuous script. That is, there were no spaces between the words and normally no divisions between verses (although some manuscripts at times include various forms of punctuation). The first line below includes the text without any markings. The second line underlines the name and titles attributed to Jesus. The third line underlines the phrase that does not appear in some manuscripts, perhaps as a result of an accidental omission. The final line includes the reading that would have resulted from the omission.

- ΑΡΧΗΤΟΥΕΥΑΓΓΕΛΙΟΥΙΥΧΥΥΥΘΥΚΑΘΩΣΓΕΓΡΑΠΤΑΙ

- ΑΡΧΗΤΟΥΕΥΑΓΓΕΛΙΟΥΙΥΧΥΥΥΘΥΚΑΘΩΣΓΕΓΡΑΠΤΑΙ

- ΑΡΧΗΤΟΥΕΥΑΓΓΕΛΙΟΥΙΥΧΥΥΥΘΥΚΑΘΩΣΓΕΓΡΑΠΤΑΙ

- ΑΡΧΗΤΟΥΕΥΑΓΓΕΛΙΟΥΙΥΧΥΚΑΘΩΣΓΕΓΡΑΠΤΑΙ

By examining each line of text, one can see the ease with which a scribe may have accidentally skipped from the final upsilon in XY to the final upsilon in ΘΥ.

Noting recent studies which claim that scribes were more careful at the beginning of a book, Ehrman claims that an accidental error is unlikely so early in the gospel.34 He writes, “It seems at least antecedently probable that a scribe would begin his work on Mark’s gospel only after having made a clean break, say, with Matthew, and that he would plunge into his work with renewed strength and vigor.”35 He supports the position by adding that א and Θ, two of the earliest to attest the omission (fourth and ninth centuries), are elaborately decorated at the end of Matthew, indicating that the scribes did not simply rush from Mathew into Mark.36 Such evidence should not be pushed too far, however, since the practices of the fourth or ninth centuries do not suggest what the practices were in prior centuries. Nonetheless, the evidence regarding accuracy at the beginning of a book does carry weight and should not be dismissed. Still, one must recognize that “renewed strength and vigor” does not eliminate the possibility of a mistake in a series of words particularly well suited to lead to scribal error.37

Ehrman also claims that, since the manuscripts which omit the title are early, unrelated, and widespread, one accidental error could not have led to the omission. Instead, it must have been the same error repeated in a wide range of traditions. “Several of the witnesses belong to different textual families,” he writes, “so that the textual variants they have in common cannot be attributed simply to a corrupt exemplar that they all used. The precise agreement of otherwise unrelated MSS therefore indicates the antiquity of a variant reading.”38 Moreover, he suggests, the fact that the later Byzantine manuscripts did not make the same error even though the Byzantine tradition was not noted for being particularly careful makes the argument more unlikely.39 Of course, this is the type of mistake that could have been made repeatedly, but Ehrman overstates the evidence to suggest that the omission survives in early manuscripts. None of the few Greek manuscripts which support the reading can be identified as early (i.e., second or third century). While the Fathers do provide an early testimony, their readings did not influence the Greek manuscript tradition until the fourth century. So, even if the reading did have limited early circulation, more than sufficient time passed for it to have made its way to diverse areas. Even further, the assertion that the manuscripts with the omission are unrelated requires attention. Indeed, the reading has support from only two Alexandrian and three Caesarean witnesses.

The second possibility suggests that the original text did not contain υἱοῦ θεοῦ, the verse having been altered to include the honorific title. Similarly, Ehrman’s proposal—the third possibility—suggests that the addition occured for theological reasons. He claims that the addition may have served to forestall an adoptionistic interpretation of the passage, a position fleshed out below.

Shorter Reading

Variant 4 clearly comprises the shortest reading. Given its extremely poor external attestation, however, this reading clearly cannot be original. Ehrman’s preference, which omits “Son of God,” is the next shortest reading and has sufficient external support to be considered possible. This gives the reading some credibility because scribes would indeed be more likely to add to a reading than shorten it.40 Ehrman proposes that the text without υἱοῦ θεοῦ was original and that a scribe concerned that the Gospel did not mention the virgin birth or pre-exist-ence of Christ added the title so that it would not appear that Jesus was adopted as the Son of God at his baptism.

Yet there is nothing in Mark 1:11 to suggest an adoptionist position. In his discussion of Luke 3:22, Ehrman goes to great length to support “Today I have begotten you” over “In you I am well-pleased” in order to argue for an adoptionist interpretation. Now, according to Ehrman, even the latter treatment of this passage implies that this reading supports adoption. However, even if Ehrman’s preferred reading in Luke 3:22 were original, given the evidence of Luke—Acts and the remainder of the New Testament, the verse could in no way be interpreted in an adoptionist manner. More specifically, the baptism in Mark to an even greater extent prohibits an adoptionist understanding.

Intrinsic Probabilities

The exact same evidence has been used to take the discussion of intrinsic probabilities in two directions. As seen below, commentators agree that the title “Son of God” plays a significant role in Mark but interpret the evidence in different ways. On one hand, some argue that the importance of the title provides sufficient reason for a scribe to add “Son of God” to a text that otherwise did not include it.41 On the other hand, some expect the introduction to the Gospel to include the title precisely because it is so significant.

Ehrman of course argues that since the title fits within Mark’s Chris-tology so well, it is a likely addition.42 Cole and Marcus both find it easier to see the title as having been added later than as having been omitted by so many of the Fathers.43 Head argues against the necessity of expecting the phrase in 1:1 simply because it is important to the Gospel. Indeed, he argues, the title is also important to Matthew but does not appear in its opening verse.44 However, while the title may be important to Matthew, it does not enjoy the same prominence in Matthew that it does in Mark. In fact, the presence of “Jesus Christ the Son of David, Son of Abraham” in Matt. 1:1 provides an appropriate beginning to a Gospel which reveals that Jesus is the Jewish Messiah. Similarly, John 1:1 indicates not only the intimate presence of Jesus with the Father but also the deity of the Son, both tremendously important themes for John. More significant is Head’s recognition that similar additions appear several other times in the Gospels, including Mark 8:29 and 14:61.45 Notably, Mark 8:29 contains Peter’s confession of Jesus in a shorter form than the other Gospels.46 Slomp argues that, since Mark is “Peter’s Gospel” and Peter’s confession in 8:29 does not include “Son of God,” the title should not appear in Mark’s first verse.47 However, the Gospel reaches its zenith not with Peter’s confession but rather with that of the centurion.

Taking the opposite position, Brooks affirms that “Son of God” is perhaps the most important title in Mark, one which appears at crucial points in the story.48 As such, one should expect it to appear in Mark 1:1. Likewise, Lane points out that the title provides the general plan for the work, and Cranfield argues for its inclusion since the title plays such an important role in the Gospel.49 Edwards agrees, noting the importance in terms of the overall purpose as well as Marcan Chris-tology. For Edwards, the title serves as a brief confession of faith which unfolds throughout the Gospel.50 Mann argues for its originality not only because of the term itself but also because of other uses of “Son” in Mark (1:11; 9:7; 14:61).51 Globe bases its originality upon Marcan style and claims that the introduction also exhibits parallels to other superscriptions, following an Old Testament pattern in order to demonstrate that the Gospel is on par with the Old Testament. Despite its sparse use, the title is indeed pivotal.52 Both Stonehouse and Perrin add that, if the title were not original, it should have been: “If these words are a gloss, they represent the action of a scribe who enjoyed a measure of real insight into the distinctiveness of Mark’s portrayal of Christ.”53

More Difficult Reading

None of the variants contains a reading which could be appropriately labeled difficult, unless one agrees that the presence of “Son of God” in the first verse of the Gospel would violate the messianic secret. Slomp, for example, proposes that following Jesus’ reserve, Mark reveals Jesus’ Sonship gradually and wants the reader to come to realize that Jesus is the Son of God in a manner similar to the centurion.54 But while there is an element of secrecy in Mark, it is a secret not for the reader but for those whom Jesus encountered during his ministry. The reader is aware of the secret and knows who Jesus is from the beginning.55 Even if the text did not originally contain the title, the Gospel affirms Jesus as Son just ten verses later. In addition, Mark identifies John’s ministry as preparing the way for the Lord (Mark 1:4). Accordingly, the title does nothing to reveal a secret which would otherwise be kept.

As Slomp suggests, Mark does indeed develop what it means for Jesus to be the Son of God, but the development does not require the reader to realize that Jesus is Son of God only at the end of the Gospel. Instead, the reader recognizes Jesus as the Son of God from the beginning and comes to realize more fully what this entails as the Gospel progresses. In contrast, Ehrman declares, “Mark does not state explicitly what he means by calling Jesus the ‘Son of God,’ nor does he indicate when this status was conferred upon him.”56 To the contrary, the entire Gospel was written to communicate what it means for Jesus to be the Son of God. The climactic confession of the centurion does not indicate for the first time that Jesus is the Son but brings to mind all that has implicitly and explicitly affirmed Jesus as Son of God.57 Furthermore, that the Gospel gives no indication of the time of conferral indicates that there was in fact no conferral.

Conclusion

Reviewing his statements, we have found not only that Ehrman frequently repeats himself but also that he overestimates or exaggerates the evidence. Ehrman claims the following:

- “In terms of antiquity and character, this [omission of υἱοῦ θεοῦ] is not a confluence of witnesses to be trifled with.”58

- “Two of the three best Alexandrian witnesses of Mark support this text [which omits υίου θεου].”59

- “This slate of witnesses [i.e., the manuscripts which omit υἱοῦ θεοῦ] is diverse both in terms of textual consanguinity and geography.”60

- The omission of υἱοῦ θεοῦ occurs in “such a wide spread of the tradition” that it cannot be accidental.61

- “Since the omission [of υἱοῦ θεοῦ] occurs at the beginning of a book, it is unlikely to be accidental.”62

- “Mark does not state explicitly what he means by calling Jesus the ‘Son of God,’ nor does he indicate when this status was conferred upon him.”63

- “The shorter text appears in relatively early, unrelated, and widespread witnesses.”64

With reference to (1), the character of Ehrman’s preferred reading is not as certain as he suggests. Instead, the inclusion of “Son of God” enjoys superior support. As for the date of the readings, the evidence is divided. We have found (2) simply to be untrue because the only Alexandrian Greek manuscript to support the reading is [א]. (3) is partially true inasmuch as the reading is diverse geographically. However, the inclusion of “Son of God” is more diverse geographically. As for textual consanguinity, Ehrman’s reading is actually quite limited.

I disagree with (4) because the reading is not so widespread that one error could not have influenced all of the relevant manuscripts. However, even if those manuscripts were completely unrelated, the error would be precisely the kind which could have been repeated. I agree with (5) that errors are less likely to occur at the beginning of a book. Nevertheless, this does not mean that an error could not have occurred. As for (6), I suggest that the Gospel as a whole does exceptionally well at indicating what it means for Jesus to be the Son of God. Additionally, that the Gospel gives no indication of the time of conferral indicates that there was in fact no conferral. That he expects otherwise speaks volumes about Ehrman’s presuppositions. Finally, (7) conflates several other points which have already been addressed. Again, it is not simply a matter of finding a reading that is diverse or relatively early but of finding one that is the most diverse and the earliest.

All in all, I give preference to the readings which include “Son of God.” Yet one cannot claim that the evidence overwhelmingly supports the originality of the title. However, even if the title were not original, a scribe could certainly have added it to emphasize the themes of the Gospel, not as a means to oppose adoptionism. Whereas Ehrman has argued that Adoptionists often used Mark’s Gospel, nothing in Mark’s baptismal account suggests that Jesus became the Son of God. Instead, the account affirms Jesus as God’s Son. Ehrman has identified one possible solution to this textual problem but has not proven his case. In fact, it may be impossible to prove. Dealing then with probability, I find other solutions more likely. In sum, even if his preferred text were original, Ehrman’s thesis is both improvable and improbable, although not impossible.

- Cf. Stanley E. Porter, “Textual Criticism,” in Dictionary of New Testament Background, ed. Craig A. Evans and Stanley E. Porter (Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 2000), 1210. ↩︎

- Cf. Reuben Swanson, ed., New Testament Greek Manuscripts: Variant Readings Arranged in Horizontal Lines Against Codex Vaticanus. Romans (Wheaton: Tyndale House, 2001), xxvi-xxvii. ↩︎

- Bruce M. Metzger and Bart D. Ehrman, The Text of the New Testament, 4th ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005); Bart D. Ehrman, Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why (New York: HarperSanFrancisco, 2005). ↩︎

- Bart D. Ehrman, The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture: The Effects of Early Chris-tological Controversies on the Text of the New Testament (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993). ↩︎

- Cf. Gerald Bray, review of The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture: The Effects of Early Christologie al Controversies on the Text of the New Testament, by Bart D. Ehrman, Churchman 108:1 (1994): 85. ↩︎

- Ehrman, Misquoting Jesus, 1—15. ↩︎

- Moisés Silva, review of The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture: The Effects of Early Christological Controversies on the Text of the New Testament, by Bart D. Ehrman, Westminster Theological Journal 57 (Spring 1995): 262. ↩︎

- Ehrman, The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture, 7. Cf. Walter Bauer, Orthodoxy and Heresy in Earliest Christianity, trans. Robert Kraft (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1971). ↩︎

- Ehrman, The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture, 25. ↩︎

- Ibid., 15-25. ↩︎

- Daniel Wallace has identified Ehrman’s omission of evidence in Misquoting Jesus. Daniel B. Wallace, “The Gospel According to Bart: A Review Article of Misquoting Jesus by Bart Ehrman,” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 49 (June 2006), 329. ↩︎

- This is not meant to denigrate Ehrman’s scholarship. In fact, my respect for his scholarship leads me to believe that he knows exactly what he is doing when he omits evidence or attempts to give it a particular slant. ↩︎

- Ehrman, The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture, xi. ↩︎

- Ehrman, The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture, 29-31. Cf. Ehrman, “The Text as Window: Manuscripts and the Social History of Early Christianity,” in The Text of the New Testament in Contemporary Research: Essays on the Status Quaestionis, ed. Bart D. Ehrman and Michael W. Holmes (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1995), 361—79. In a previous essay, which contained the argument of The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture in an incipient form, Ehrman likened scribal habits to the recreation of texts which takes place in reader—response criticism. Ehrman, “The Text of Mark in the Hands of the Orthodox,” in Biblical Hermeneutics in Historical Perspective, ed. Mark S. Burrows and Paul Rorem (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1991), 22. ↩︎

- Ehrman, The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture, 67, emphasis added. ↩︎

- In Misquoting Jesus, Ehrman appears to back away from his former interpretation, stating that “Luke probably did not intend to be interpreted adoptionistically.” Ehrman, Misquoting Jesus, 160. ↩︎

- Barbara Aland, Kurt Aland, Johannes Karavidopoulos, Carlo M. Martini, and Bruce M. Metzger, The Greek New Testament, 4th rev. ed. (Stuttgart: United Bible Societies, 1994), 6-36 (identified as UBS4). The UBS4 committee includes letter evaluations of readings to express the degree of certainty regarding the originality of a text. This text has a “C” rating, indicating that the “Committee had difficulty in deciding which variant to place in the text.” Aland et al., Greek New Testament, 3. ↩︎

- The classification of manuscript evidence noted in the table derives from Bruce M. Metzger, The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration, 3d ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), 36-92; Kurt Aland and Barbara Aland, The Text of the New Testament: An Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism, 2d ed., trans. Erroll E Rhodes (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1981), 96-138; and UBS4. The support for each reading is grouped according to textual family. In each column, the manuscript designation appears followed by the estimated date of the manuscript. To illustrate, the first reading has support from manuscript B, a fourth-century manuscript of the Alexandrian text type. ↩︎

- Porter, 1213. ↩︎

- Ehrman, The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture, 72. ↩︎

- Ibid., 72-73. ↩︎

- Ibid., 73. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Alexander Globe, “The Caesarean Omission of the Phrase ‘Son of God’ in Mark 1:1,” Harvard Theological Review 75 (April 1982): 215-16. ↩︎

- Ehrman, The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture, 73. ↩︎

- Ibid., 72-74. ↩︎

- Ehrman identifies manuscript 1555 as support for his reading, but neither UBS4 nor NA27 include the manuscript in the apparatus. However, he himself identifies this as a Western witness, so it cannot solve the dilemma. ↩︎

- Globe, “The Caesarean Omission,” 218. Likewise, Marcus affirms that the inclusion has support not only from a larger number of manuscripts but also from very good manuscripts. Joel Marcus, Mark 1—8, The Anchor Bible, ed. William Foxwell Albright and David Noel Freedman, vol. 27 (New York: Doubleday, 2000), 141. Head admits that the inclusion of the title has broader geographic distribution but points out that the reading is limited almost entirely to the Latin Fathers. He expresses concern that some approaches do not give proper weight to the absence of the reading in the Greek Fathers. Peter M. Head, “A Text-Critical Study of Mark 1.1: ‘The Beginning of the Gospel of Jesus Christ,'” New Testament Studies 37 (October 1991): 623-26. Cranfield points out in turn that the omission by a patristic writer is not significant if the writer was not addressing the particular point in question. He further notes that Irenaeus and Epiphanius even omit “Jesus Christ” here. C. E. B. Cranfield, The Gospel According to St. Mark, Cambridge Greek Testament, ed. C. F. D. Moule (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1959), 39. ↩︎

- James R. Edwards, The Gospel According to Mark, The Pillar New Testament Commentary, ed. D. A. Carson (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002), 25-26; James A. Brooks, Mark, The New American Commentary, ed. David S. Dockery, vol. 23 (Nashville: Broadman, 1991), 39; David E. Garland, Mark, The NIV Application Commentary, ed. Terry Muck (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1996), 23; Cranfield, The Gospel According to St. Mark, 38; C. H. Turner, “A Textual Commentary on Mark 1,” The Journal of Theological Studies 28 (January 1927): 150; William L. Lane, The Gospel According to Mark, New International Commentary on the New Testament, ed. F. F. Bruce (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1974), 41. ↩︎

- Head suggests that the use of nomina sacra was intended to draw attention to the highlighted terms, not simply to serve as abbreviations. As such, he dismisses the likelihood of an error occurring by homoioteleuton. Head, “A Text-Critical Study of Mark 1.1,” 628. However, in reviewing ancient manuscripts, one finds that the nomina sacra could be missed as easily as any other words, particularly in a series such as this. ↩︎

- Cf. Head, “A Text-Critical Study of Mark 1.1,” 629. ↩︎

- Ehrman, The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture, 73. ↩︎

- Ibid., 73-74. ↩︎

- Globe suggests that a similar error occurred in codex 28 with the omission of Χριστοῦ after Ἰησοῦ, an error later corrected in the manuscript. Globe, 216-17. ↩︎

- Ehrman, “The Text of Mark in the Hands of the Orthodox,” 27 n. 17. ↩︎

- Ehrman, The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture, 73. ↩︎

- I agree with Ehrman that, if the changes in the manuscript tradition were intentional, the omission would then stand a much greater chance of being original. Ehrman, The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture, 74. Cranfield agrees that scribes were more likely to add the phrase, yet he still finds good reasons for its originality. Cranfield, The Gospel According to St. Mark, 39. ↩︎

- Croy takes a different tack, proposing that the beginning of the Gospel was defective and that it circulated early without any form of Mark 1:1. Subsequently, scribes added a note to indicate where the Gospel begins. N. Clayton Croy, “Where the Gospel Text Begins: A Non-Theological Interpretation of Mark 1:1,” Novum Testamentum 43 (April 2001): 119. ↩︎

- Ehrman, The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture, 74. ↩︎

- R. A. Cole, The Gospel According to St. Mark: An Introduction and Commentary (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1961), 56; Marcus, 141. ↩︎

- Head, “A Text-Critical Study of Mark 1.1,” 627. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- None of the Gospels provide readings parallel to the Marcan introduction. One comes closest to finding parallels through the use of the title in Mark (cf. 3:11, 5:7, and 15:39). The addition to Mark 8:29, a harmonization with Peter’s confession in the other Gospels, points to the scribal tendency to harmonize and conflate, evidence one may use to argue against the inclusion of “Son of God” in Mark 1:1. ↩︎

- Jan Slomp, “Are the Words 4Son of God’ in Mark 1.1 Original?” The Bible Translator 28 (January 1977): 147. ↩︎

- Brooks, Mark, 39. ↩︎

- Lane, The Gospel According to Mark, 41; Cranfield, The Gospel According to St. Mark, 39. ↩︎

- Edwards, The Gospel According to Mark, 25-26. ↩︎

- C. S. Mann, Mark, The Anchor Bible, ed. William Foxwell Albright and David Noel Freedman, vol. 27 (Garden City: Doubleday, 1986), 194. ↩︎

- Globe, “The Caesarean Omission,” 217-18. Globe points to similar beginnings in Prov. 1:1, Eccles. 1:1, Song of Sol. 1:1, Isa. 1:1, Hos. 1:1-2, Amos 1:1, Joel 1:1, Nah. 1:1, Zeph. 1:1, and Mal. 1:1. ↩︎

- Ν. Β. Stonehouse, The Witness of Matthew and Mark to Christ (London: Tyndale, 1944), 12; Norman Perrin, A Modern Pilgrimage in New Testament Christology (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1974), 115. ↩︎

- Slomp, “Are the Words ‘Son of God’ in Mark 1.1 Original?” 148. Cf. Oscar Cullmann, The Christology of the New Testament (London: S.C.M., 1963), 278, 94. ↩︎

- Brooks, Mark, 39. ↩︎

- Ehrman, The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture, 74. This comment explains why his description of the Son of God in his New Testament introduction lacks substance. He uses appropriate categories but does not flesh them out sufficiently and fails to answer the question, “What does it mean for Mark to say that Jesus is the Son of God?” Ehrman, The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings, 2d ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), 60-75. ↩︎

- Ehrman goes so far as to say that it is not clear whether the centurion means that Jesus is the Son of the only true God or that Jesus is a divine man, one of the sons of the gods. Given what transpires in the Gospel, it is impossible that a writer would give climactic place to a statement which meant only that Jesus is one of the sons of the gods. What else in Mark would suggest that there is more than one God? Ehrman, The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture, 110 n. 140. ↩︎

- Ibid., 72. ↩︎

- Ibid., 72-73. ↩︎

- Ibid., 73. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid., 73. ↩︎

- Ibid., 74. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎