The Use of the Old Testament in the New Testament

Southwestern Journal of Theology

Volume 64, No. 1 – Fall 2021

Editor: David S. Dockery

I. THE STORY CONTINUES…

Northrop Frye, the Canadian literary critic, states the immediate context of a sentence is as likely to be three hundred pages off as to be the next or preceding sentence.11 This is especially true in the Scriptures. The Bible is one story because it has one divine author who brings all of the disparate pieces into cohesion.

Acts continues the grand narrative of the Scriptures. Brian Rosner has argued Acts parallels the history found in the OT and therefore should be labeled simply as salvation history.2 According to Rosner, five pieces of evidence support this from Acts:

- the imitation of the Septuagint in language and style,

- the language of fulfillment in Acts,

- the depictions of events similar to the OT,

- the historical summaries found in Acts 2, 7, and 13 are narrative

accounts of OT history to highlight continuing participation in

that history, and - a theological understanding of history in which God is in control.

The result of these editorial techniques communicates that Luke continues the story of Israel where it left off. If one splits Acts into three sections (as will be argued below), each of them recounts Israel’s history climaxing in Jesus (Acts 2; 7; 13).3 Acts is not only history, but holy history—an extension of the story that began in Genesis 1.

Though there are many ways we could examine the OT in Acts, I will look to the macro-structure of Acts, showing how it follows and fulfills the promises of the OT.4 Some only look to what is explicit and ignore what is implicit. I will therefore examine not only the explicit citations, but look at how Luke has ordered his narrative. Large swaths of the narrative can be seen as “fulfillment” texts, even when Luke does not make his subtext explicit. In this way, this article will be different from most “OT in Acts” examinations.

The justification for this method comes from Luke’s own writing. Luke is the only author in the NT to give us prescripts for both of his volumes (Luke 1:1–4; Acts 1:1–5), which end up being quite helpful in determining what he is attempting to accomplish. In Luke 1:1–4 readers learn Luke writes an “ordered” (kathexēs) “narrative” (diēgēsis) about the things that have been “fulfilled” (plērophoreō) among them. To put this another way, Luke writes his stories in a certain order to show that God fulfills his promises to Israel. This gives justification for examining the larger swaths of his structure to see how the OT story formed his imagination and directed his storytelling.

II. JERUSALEM, JUDEA, AND SAMARIA, AND THE ENDS OF THE EARTH

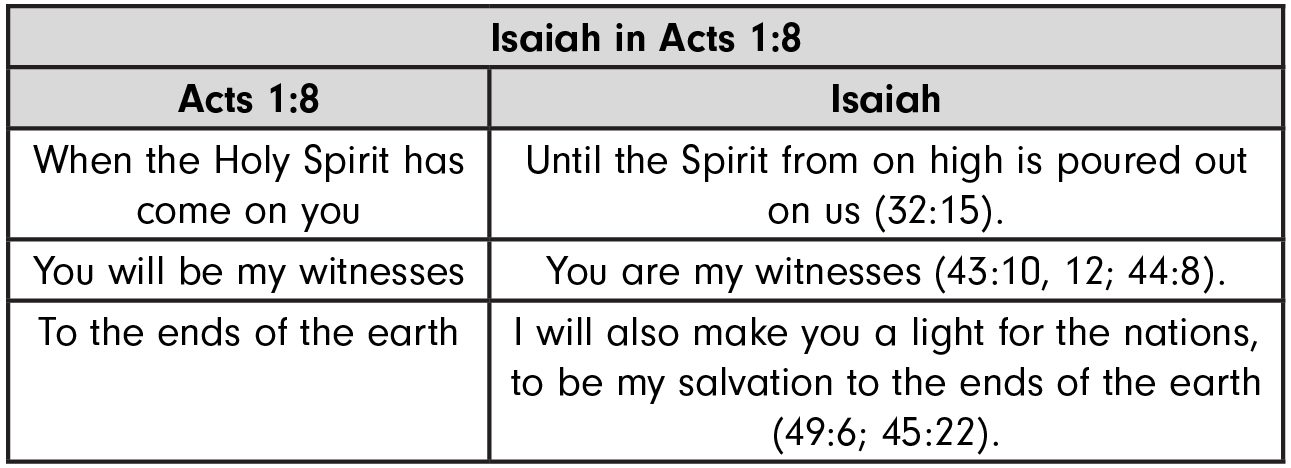

Many scholars argue that Acts 1:8 functions as the table of contents for Acts.5 Before Jesus ascends, he gives the apostles their commission: “But you will receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you, and you will be my witnesses in Jerusalem and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth” (Acts 1:8).6 A distinctly geographical presentation of the spread of the good news exists in Acts, and the order is important. The blessings to the nations will come forth from Jerusalem because God promised Abraham that his children would bless the nations (Gen 12:3; Isa 49:6; Acts 13:47). The order, however, is not only geographical (Jerusalem—Rome), but ethnic (Jew—Gentile) and theopolitical (Jesus the King—Caesar).7 Salvation comes to Jerusalem, Israel is reconstituted and reunified (Judea and Samaria), and Gentiles are included (the ends of the earth; cf. Acts 13:31; 26:16–23; see also Isa 48:20; Jer 10:13).

Even the commission itself in Acts 1:8 is filled with OT allusions, particularly from Isaiah. The Holy Spirit is promised in Isaiah, the servant (Israel/Jesus) is called to be Yahweh’s witnesses, and they are both called to be a light to ends of the earth. Luke has set up his narrative as a fulfillment of the new exodus prophetic predictions.8

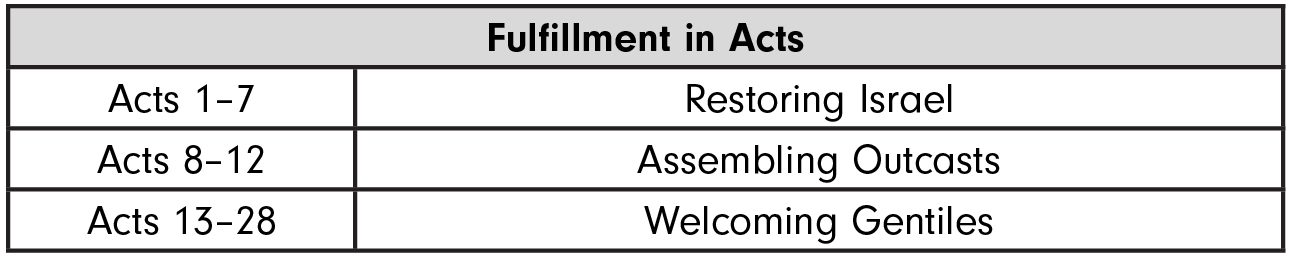

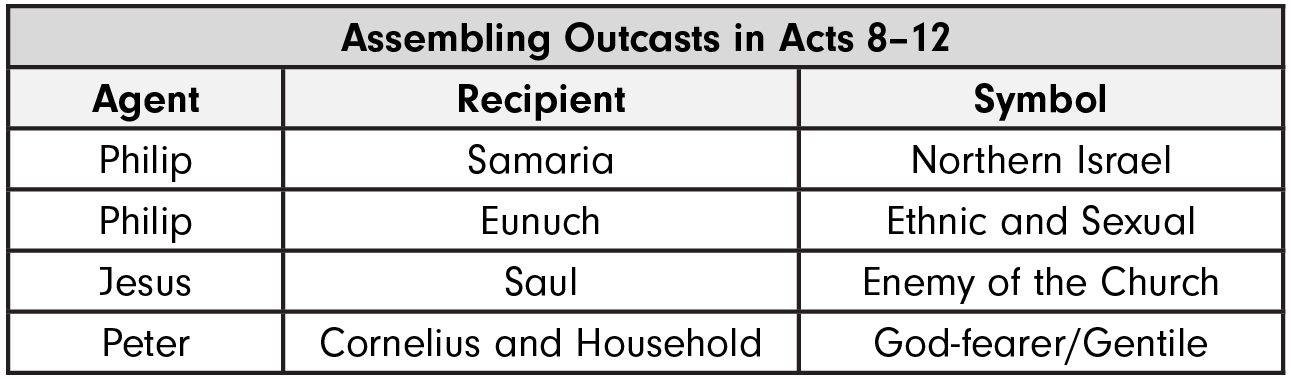

If one follows the division of territories found in Acts 1:8, then three panels for the progression of the church appear: restoring Israel, assembling outcasts, and welcoming Gentiles.9 Jerusalem is appropriately first as God chose Israel. Then the word spreads to outcasts in Israel (Samaritans, a eunuch, an enemy of the church, and a god-fearing Gentile household). Finally, the Gentile mission commences. God establishes a new people comprised of various people groups. We will examine each panel on the next page, looking to the large patterns in the narrative and see how Luke has ordered his narrative to display this as both a new story and an old story.

III. RESTORING ISRAEL (ACTS 1–7)

The first stage is Israel’s restoration (Acts 1–7). The first seven chapters of Acts focus on Jerusalem and the temple. As James Dunn states, “It began in Jerusalem. That is the first clear message which Luke wants his readers to understand.”10 God’s temple blessings flow from and through Israel. The first section thus demarcates the remnant of Israel. Some respond positively, but others, especially the temple leaders, reject this life and continue to cling to the old temple.

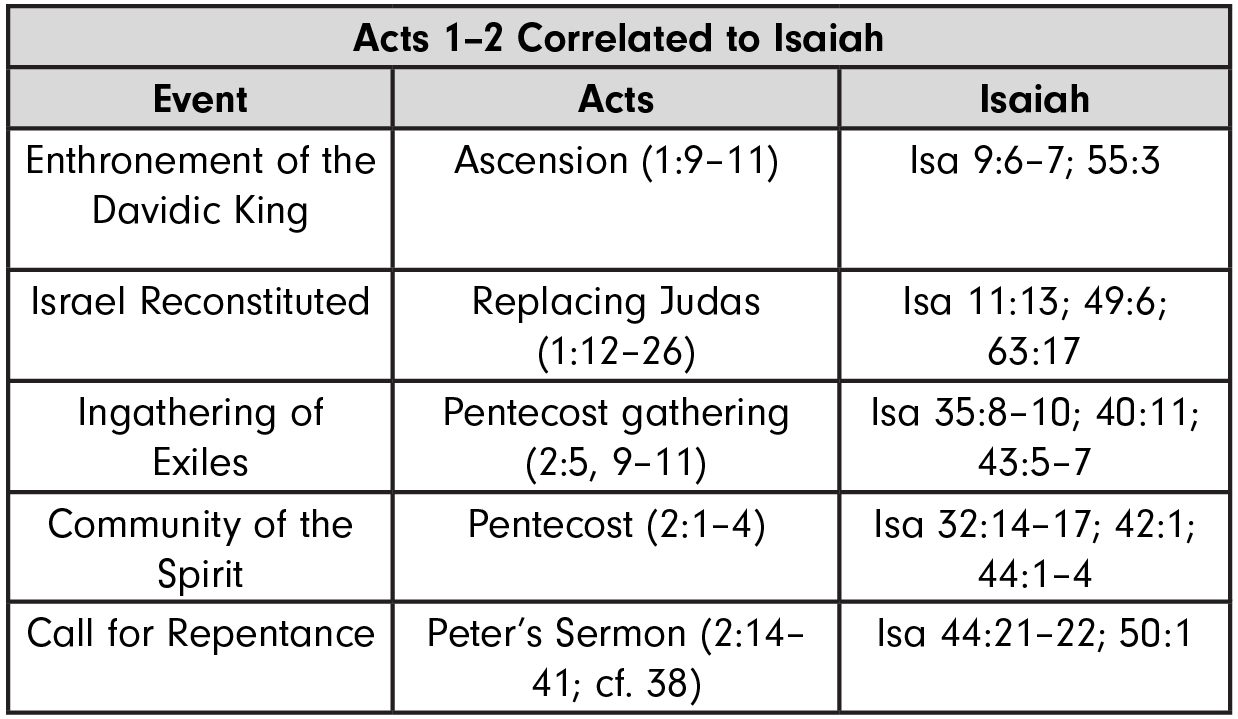

1. Acts 1–2. Acts begins with Jesus commanding his disciples to wait for the promised Spirit in Jerusalem. This is a key promise that inaugurates Israel’s renewal (Jer 31:31–34; Ezek 36:26–27). After this, the narrative pattern in Acts 1–2 closely follows the promises made in the prophets: the Davidic king is exalted and enthroned (the ascension), Israel is symbolically reunited (choosing of Matthias), the exiles are gathered from the nations, and the Spirit is poured out on the new people of God (Pentecost). Then all the people are called to covenantal repentance. They turn to the Lord, becoming the ideal Torah community.

After the prologue (1:1–5) and commission (1:6–8), the narrative centers on Jesus’s ascension (1:9–11). The event is the fulfillment of the promise that a Davidic King would be enthroned and reign forever (Pss 2, 110; Dan 7). Now that the Davidic King has been enthroned, he will build a “house” for Yahweh (2 Sam 7:2). The place of Jesus’s reign becomes the ground for mission to the ends of the earth. The rest of the NT essentially recounts the growth and struggle of these Jesus communities as they pop up all over the Greco-Roman world. They call all nations to believe because Jesus reigns over all. The spread of the gospel geographically and the birth of the church is inseparable from Christ’s cosmic reign in the heavens.

After the Davidic King is enthroned, he will restore his people. Israel’s restoration is indicated in the choosing of Matthias as the twelfth apostle (Acts 1:15–26). Though many struggle to know what to do with the placement of this narrative, at least one of Luke’s points is that the choice of the twelfth disciple makes symbolic Israel whole again (Luke 22:30; Acts 26:7). This is indicated as the emphasis on “numbering” the eleven or twelve abounds in these verses (Acts 1:13, 17a, 26b). God has promised he will “raise up the tribes of Jacob and to bring back the preserved of Israel” (Isa 49:6) and “Ephraim’s envy will cease; Judah’s harassing will end” (Isa 11:13). Now Israel’s reconstitution is partially fulfilled as the twelfth disciple is chosen, thus reuniting the tribes separated at the time of Solomon.

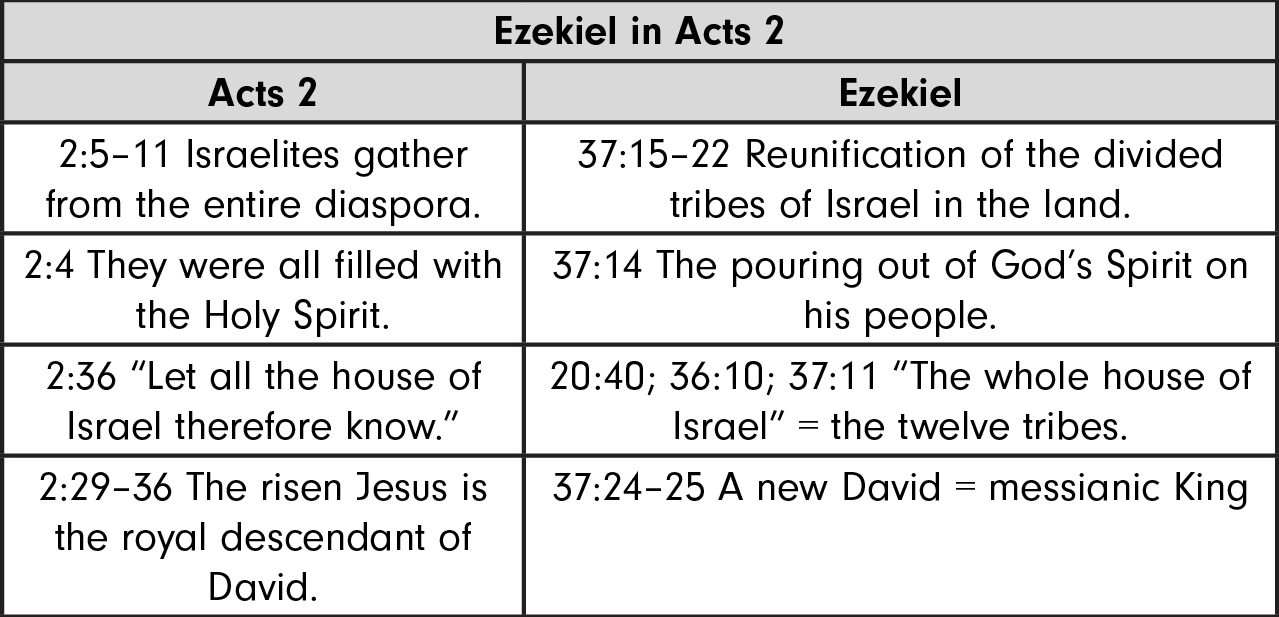

Pentecost also restores Israel by gathering exiles scattered abroad. Pentecost was a pilgrimage festival where Jews from all nations would gather into their city. The Spirit falls at Pentecost because God had regathered Israel (Isa 44:1–4). God had promised he would bring his offspring from the east, west, north, and south (Isa 43:5–7; Acts 2:9–11). Therefore, the Spirit comes at Pentecost to reconstitute the gathered people of God. Not only have the twelve tribes been symbolically reunited, but also the exiles of Israel scattered during the reign of Assyria, Babylon, Persia, Greece, and Rome are regathered. Pentecost also symbolizes the establishment of the new temple because those gathered receive the presence of God. In Ezekiel, God’s Spirit departed from the temple, and in Ezra, it did not return. Now the Spirit descends again. The new era is here (Luke 3:16–17; Acts 2:22–36).

The remaking of Israel continues as Peter’s Pentecost sermon is directed to Jews. He speaks to them as Jewish men (Acts 2:14), Israelites (2:22), and “all the house of Israel” (2:36). In Ezekiel 37, “all the house of Israel” is associated with the regathering of Israel’s exiles (37:21), the restoration of the north and south (37:15–22), the resurrection of Israel (37:15–22), the reign of the Davidic King (37:24–25), and the dwelling of God with his people (37:26–28). Acts 2 as a whole condenses restoration images found in Ezekiel.11

Further supporting the establishment of God’s people at Pentecost is the content of Peter’s sermon (2:14–41). It becomes a textbook example of how God has fulfilled his promises to Israel in the resurrection and ascension of Jesus and the gift of the Spirit. All the passages Peter cites explain this is part of God’s plan: God promised the Spirit (Joel 2:28–32), the resurrection (Ps 16:8–11), and the ascension (Ps 110:1). Peter then tells Israel they must repent and be baptized in the name of Jesus (Acts 2:38) to be renewed. This message of repentance reiterates the prophets’ message to Israel (Joel 2:12–14; Jer 4:28). The new people of God are defined around the ascended Christ. They are to show their participation in the new community by going through water like the Israel of old.

Three-thousand people respond to Peter’s message. The 3,000 that died in Exodus 32:28 by the sword of the Levites at Sinai are raised to new life as 3,000 respond to Peter’s message. Two passages (2:44–47; 4:32–35) detail the practices of this new community: generosity, teaching, breaking of bread, fellowship, and prayer. The Torah community in the OT was to be generous by cancelling debt and not having anyone poor among them (Deut 15:1–4).

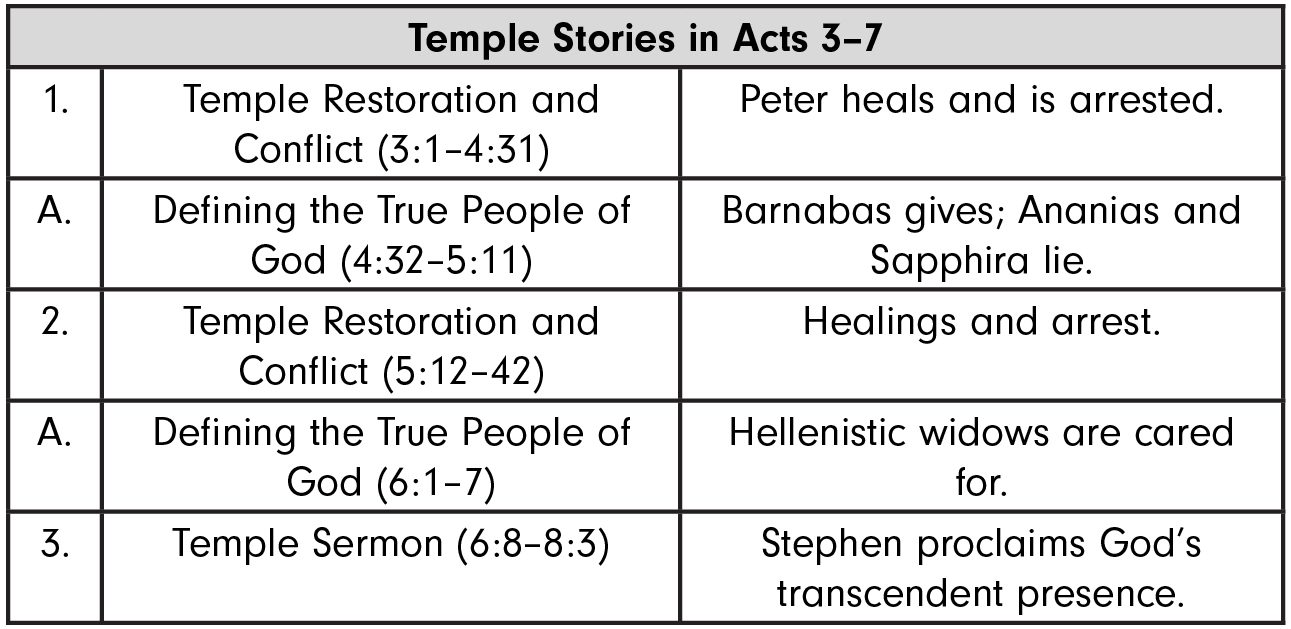

2. Acts 3–7. Acts 3–7 can also to be read through the lens of Israel’s restoration. This is indicated by the temple focus until the end of chapter seven. An inclusio links Acts 2:46 and 5:42, which places the intervening narrative under the banner of “temple actions”:

And day by day, attending the temple together and breaking bread in their homes, they received their food with glad and generous hearts. (Acts 2:46)

And every day, in the temple and from house to house, they did not cease teaching and preaching that the Christ is Jesus. (Acts 5:42)

Between these texts are two temple restoration and conflict narratives, two interludes defining the people of God, and finally the section ends with Stephen’s climactic temple sermon. It can be viewed visually like this:

In the first temple restoration and conflict story, Peter heals a lame man who sits outside of the temple (Acts 3:2–3) and who is then welcomed into the temple once he is made whole (Acts 3:8). This man symbolizes Israel’s destitution and points to the nation’s restoration. Luke closes the narrative with a seemingly insignificant note that this man had been deformed for over forty years (4:22). However, by ending this way, the lame man becomes a symbol of hope for the disenfranchised of the nation. The Israelites wandered in the wilderness for forty years, but they did not enter their land. This man sat outside the temple waiting forty years; now resurrection life and rest has come through the Servant. The new era has finally dawned upon Israel, but to be healed people must follow their Servant like Moses.12 Boundary-crossing and border-transgressing realities mark the Spirit’s presence.

A rich OT tradition includes the lame at the day of salvation. Jeremiah said God would gather his people from the remote regions of the earth “the blind and the lame will be with them” (Jer 31:8). In Zeph 3:19 it says, “I will save the lame and gather the outcasts; I will make those who were disgraced throughout the earth receive praise and fame.” Micah 4:6–7 speaks similarly:

On that day—this is the Lord’s declaration— I will assemble the lame and gather the scattered, those I have injured. I will make the lame into a remnant, those far removed into a strong nation. Then the Lord will reign over them in Mount Zion from this time on and forever. (Emphasis added)

Peter takes the lame man by the right hand, raises him up, and the man enters the temple and begins walking, leaping, and praising God.13 Luke employs a rare word for the man’s “jumping” (hallomai). This word is also found in Isaiah when the prophet speaks of the lame leaping like a deer (Isa 35:6). The priests and captain of the temple oppose the apostles (4:1); Peter preaches Jesus as the rejected stone (4:11; Ps 118:22); and then God shakes the earth again like at Sinai when his people pray (4:31). The narrative is filled with temple themes. A new temple community has arrived with Jesus as the cornerstone.

A small narrative in Acts 4:32–5:11 further defines Israel, building on the summary in 2:44–47. Barnabas’s generosity in the new community is contrasted to Ananias and Sapphira. The temple was more than a religious center; it was also a social, political, and economic center from which the blessings of God flowed to the world. Luke highlights the gift of Barnabas, who is a Cyprian Levite. Levites were set apart to perform priestly duties (Num 1:47–53) following the golden calf incident (Ex 32:26–29). A new Levite joins the community in contrast to the priestly rulers who oppose Peter and John (Acts 4:1).

Luke, however, juxtaposes Barnabas’s generosity with Ananias and Sapphira, who lie about their gift. The OT echoes point to their action being not merely an arbitrary sin, but an improper temple offering in contrast to the Levite’s gift.14 Jeremiah condemned the temple for becoming a den of robbers, and God’s judgment is banishment from his presence (Jer 7:11, 15). Allusions to Ezekiel 20 also arise in the midst of a restoration text when the Lord says, “I will purge those of you who rebel and transgress against me” (Ezek 20:38). Then the Lord will accept his people as a pleasing aroma and will demonstrate his holiness through them in the sight of the nations (Ezek 20:41). Ananias and Sapphira’s dead bodies are removed, keeping the holy space pure as when Achan was removed in the wilderness (Joshua 7). The boundaries of the new congregation of God are defined.

The second temple narrative is similar to the first, but this time the focus is on opposition (5:12–42). Yet God redeems the new congregation from their troubles and Gamaliel notes that if these men are doing God’s work it will not be stopped. A second transition occurs with the selection of the seven to serve Hellenistic widows (6:1–7). Now the concern fans out not away from Israel, but to those who are influenced by Greek culture. Their Greek inculturation caused them to be objects of scorn, but God has already indicated he is bringing people in from the margins (Acts 2:9–11; Isa 43:5–7). The barriers between Hellenized and Hebraic Jews are overcome as seven Hellenistic leaders are chosen to care for Hellenistic widows. As the community expands, God directs its generosity to all who enter and also introduces the Hellenized leaders, Stephen and Philip. Even priests end up believing (6:7).

The Jerusalem narrative cycle comes to a climax at Stephen’s trial, speech, and death (6:8–8:3). Opposition has been escalating, and now a Hellenized witness is martyred. Stephen is accused of disrespecting the temple and law. He responds with a salvation historical argument about the temporary and corrupt nature of the physical temple and the reception of God’s prophets through history.

Stephen shows God’s transcendent presence will not be limited by any building, region, or even people group; it is found only in the person of Jesus. God appeared to Abraham in a foreign land (7:2). He was with Joseph and Moses in Egypt (7:9, 20). God appeared to Moses in the burning bush while in Midian (7:30–33). God appeared to Moses at Mount Sinai (7:38). These were all outside the land and before the temple. Stephen refutes the physical temple as a necessity for God’s presence, though it functioned as a blessing in its time. God is not and cannot be localized, and he spreads his temple presence to all who repent and believe. Stephen’s sermon becomes the theological foundation for the gospel to go to the ends of the earth.

Acts 1–7 is about the renewal of Israel. It concerns God’s temple people and the invitation for Israel to be restored to God through faith in the Messiah. Many welcome this message and are engrafted into the community, but others reject it. The good news of Jesus Christ is proclaimed to both the Hebraic and Hellenized Jews in Jerusalem. Now expansion of God’s people begins as Stephen’s blood colors the earth.

IV. ASSEMBLING OUTCASTS (ACTS 8–12)

In Acts 8–12, the message spreads to outcasts as the gospel goes to Judea and Samaria.15 God assembles people on the margins of Israel. The glory of the temple will no longer be restricted to Jerusalem. Rivers of living water flow to the outer courts, breaking down walls and bringing life. Not only will the new community be restored to its previous state, but new members are received into it as well.

This assembling of outcasts fulfills promises of the OT. In Isa 56:8, the prophet writes, “The Lord God, who gathers the outcasts of Israel, declares, ‘I will gather yet others to him besides those already gathered.’” He tells them to “let the outcasts of Moab sojourn among you” (Isa 16:4). A variety of vignettes occur in Acts 8–12:

The Philip narrative has two parts, both dealing with those on the outskirts of Judaism: Samaritans and an Ethiopian eunuch. Both are outcasts and have an uncomfortable relationship with the temple. Samaritans rejected the Jerusalem temple, and eunuchs could not even pass through the court of the Gentiles. But God refused to be bound by temple obstacles.

Samaria was separated socially, geographically, and even religiously from their Jerusalem kin.16 Most importantly, they worshiped on a different mountain: Mount Gerizim. The background to the relationship between Jews and Samaritans goes back to 1 Kings 12 and the rebellion of the Northern Kingdom against the Southern Kingdom. Samaritans were thus viewed as descendants of Jeroboam’s rebellion against the house of David (1 Kgs 12:16–20).

Nonetheless, Samaria receives the word with much joy (Acts 8:8). Philip’s mission overcomes nationalistic borders and ethnic prejudices. Before the Gentile outreach can commence, Israel’s north and south must be reintegrated. The hope of the prophets was that all Israel would be reassembled through the power of God’s Spirit. Ezekiel speaks of a time when the stick of Judah (the South) and stick of Ephraim (the North) will be joined together (Ezek 37:16–17). Yahweh will “make them one nation in the land…with one king to rule over all of them. They will no longer be two nations and will no longer be divided into two kingdoms. They will not defile themselves anymore with idols, their abhorrent things and all their transgressions. I will save them…I will cleanse them. Then they will be my people, and I will be their God. My servant David will be King over them” (Ezek 37:22–24a).

This welcoming of the Samaritans into the new community is confirmed by the strange account of the delayed reception of the Spirit (Acts 8:14–17). The Jerusalem apostles must come, pray, and lay hands on them before they receive the Spirit. The “delay” of the Spirit can be confusing. To some it looks like those in Samaria were saved and then received the Spirit, indicating a second blessing or a two-stage experience of faith—water baptism and then Holy Spirit baptism. But this more likely is an exceptional circumstance recounted because of the rift between Jerusalem and Samaria. Samaria must wait for the Spirit, and Jerusalem must witness it. The outcome, therefore, is twofold—making an impression on both the Samaritans and the apostles. The Jerusalem apostles are convinced of God’s love for the Samaritans as they witness the pouring out of the Spirit, which is a mark of the new age (Acts 2, 8, 10; cf. Luke 3:16). The Samaritans see they are connected to and not separate from the Jerusalem church.

Philip then goes south to a eunuch at the energizing direction of the Spirit. As Mikael Parsons asserts, with this episode, Luke radically redraws the map of who is in and who is out under Scriptural warrant.17 Though Luke describes this character in great detail, the label “eunuch” sticks out, pointing primarily to gender and ethnic inclusion themes.

Being a eunuch means he was emasculated. Eunuchs were both demonized and prized: demonized because of their sexual ambiguity and prized because of their trustworthiness. They were considered effeminate or “non-men,” sitting between the male-female binary. Philo writes that eunuchs are “neither male nor female” (Somn. 2.184). Yet it is significant that the eunuch in Acts 8 is still described as a man. He is also an Ethiopian—a black man. Ethiopia was a remote land according to the Scriptures (Est 1:1; 8:9; Ezek 29:10), and Ethiopians were dark-complexioned people (Jer 13:23), often used as the standard against which antiquity measured other people of color. The Ethiopian embodied the distant south. In the Jewish Scriptures, eunuchs are ritually unclean and kept out of the temple (Lev 21:20; 22:24; Deut 23:1). Nevertheless, Philip explains Jesus to him and he baptizes him on the desert road. As the eunuch reads Isaiah 53, Isaiah 56 is fulfilled—which is only a few inches down on the Isaiah scroll.

No foreigner who has joined himself to the LORD should say, “The LORD will exclude me from his people,” and the eunuch should not say, “Look, I am a dried-up tree.” For the LORD says this: “For the eunuchs who keep my Sabbaths, and choose what pleases me, and hold firmly to my covenant, I will give them, in my house and within my walls, a memorial and a name better than sons and daughters. I will give each of them an everlasting name that will never be cut off. (Isa 56:3–5)

The third narrative of an outcast welcomed is Saul. An adversary of the church is changed by a vision of Jesus. The great enemy of the church is installed as the great missionary of the church. Throughout this text, the central imagery concerns light and darkness. After Saul sees the light of Jesus, he is commissioned to bring this light to the Gentiles. Jesus’s blinding appearance to Saul reminds readers of Ezekiel’s vision when the heavens were opened and he saw brilliant light all around him (Ezek 1:1–25). In the Ezekiel scene, the creatures and throne are described in great detail, but the “human” on the throne is given only three verses because the light is too bright (Ezek 1:26–28).

Later references make it clear that the light Paul saw was Jesus himself (Acts 9:5; 27; 22:14–15; 26:16) and his heavenly glory (2 Cor 4:6). Now Saul looks up, and Jesus is revealed as the one on the throne. What Ezekiel could not see with clarity, Saul now beholds. Saul is welcomed into the new community symbolically by Ananias. In Acts 9:17–19, Ananias places his hands on Saul calling him brother. The dark state of Saul after seeing Jesus should be contrasted to Saul recovering sight. Someone from the North, the South, and now a great enemy of the church, has been welcomed.

The fourth narrative of an outcast assembled concerns Cornelius. Peter has a vision where it is revealed to him that God-fearing Gentiles (even a centurion) are welcome into the community in their Gentileness (10:34–35). Heavenly dreams, divine initiative, and the Spirit descending drive the narrative as Peter is drawn toward a Roman centurion. While Jews had little reason to resent those from Ethiopia, they had considerable problems with Romans, especially officers.

The final narrative concerning outcasts occurs in Antioch (11:19–30). Antioch was the third largest city in the Roman Empire, a cosmopolitan city full of gods, and it became a key mission base for Gentile outreach (13:1–4; 14:26–28; 15:22–23, 30–35). Though Jerusalem is not eclipsed, Antioch functions as the “mother church” for Gentiles. The narrative about Antioch shows the inclusion multiplies as a new ekklēsia is birthed north of Jerusalem.

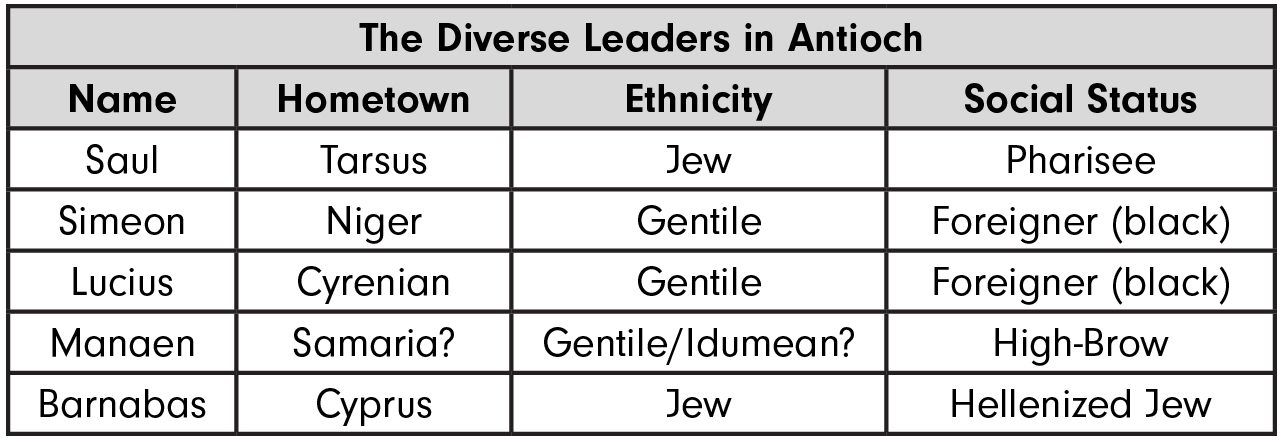

In Antioch the disciples are first called Christians (11:26). The term “Christian” parallels Latin political terms and further signals a shift of focus away from Judea to the larger Roman world. In fact, “Christian” is a Greek word of Latin form and Semitic background, thus encapsulating the cosmopolitan context of early Christianity. A new name is coined for a new identity and mission. The origin of the most popular English term for Jesus followers was based on a multiethnic reality. In Acts 13:1, Luke identifies the leaders of this diverse community in Antioch: “Now there were in the church at Antioch prophets and teachers, Barnabas, Simeon who was called Niger, Lucius of Cyrene, Manaen a lifelong friend of Herod the tetrarch, and Saul.” The extra descriptors are important.

Barnabas (a Hellenized Jew) and Saul (a Pharisee) bookend the list and will receive the attention moving forward. Three other individuals are named, indicating the assorted nature of this assembly. Simeon, is also called “Niger” which is Latin for “black,” and likely indicates a southern origin. Lucius is of Cyrene, which is in North Africa. Manaen is described as being reared with Herod the tetrarch.18 This is the same Herod (Antipas) in Luke 3:1 and Acts 4:27 who conspired against Jesus. Manaen was therefore likely of “high-society,” a childhood companion of the king.

Luke’s list is therefore quite instructive. Saul is from Tarsus but trained as a Pharisee. Barnabas, a native of Cyprus, was a Jew of diaspora with a priestly background. There are two black men from the south, and a man who had considerable social standing. The leaders in Antioch contained a pharisaical Jew, two men from Africa, a Hellenized Jew, and a privileged person. No wonder in Antioch they are first called “Christians.”

Each of these narratives (Philip, Saul, Peter, and Antioch) are vignettes of God welcoming outcasts and enfolding them into his people. God had promised he would gather others besides those already gathered (Isa 56:8). Now God’s plan comes to fruition as the apostles preach Christ and those that receive their message are filled with the Spirt.

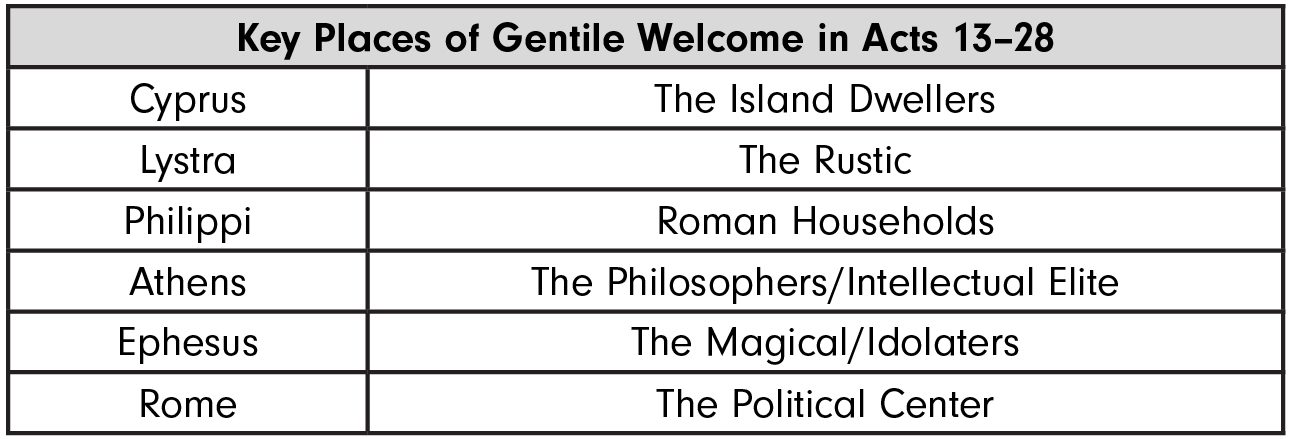

V. GENTILES WELCOMED (ACTS 13–28)

Luke has traced the restoration of Israel (1–7) and the assembling of outcasts (8–12). Now the gospel will go to predominantly Gentile territories, even if they still preach to Jews first (13–28). Though I have divided these sections, there are precursors to this Gentile mission. The eunuch has been welcomed, Peter went into the house of Cornelius, and the church in Antioch has been established. Yet a sanctioned mission to the Gentiles has not commenced. Acts 13–28 marks a shift with Paul’s journeys as the gospel goes to the ends of the earth.

The mission to the ends of the earth comes from Isa 49:6: “It is not enough for you to be my servant raising up the tribes of Jacob and restoring the protected ones of Israel. I will also make you a light for the nations, to be my salvation to the ends of the earth.” The restoration of the kingdom of Israel comes about by the power of the Spirit, through the witness of the apostles, and throughout the whole world. Isaiah’s new covenant predictions and servant commission are being fulfilled.19

Not every narrative will be covered in Paul’s journeys. Rather, I will focus on key places that represent the welcoming of all peoples. The different areas Paul visits stand as symbols for the diverse community God builds. As there are different types of Jews, there are different types of Gentiles. All peoples are welcomed: island dwellers, rustic, intellectual, religious, and political.

Paul’s mission begins with him going to Cyprus (13:4–12). Two points about this narrative should be highlighted. First, Cyprus is an island. Like mountains, islands were viewed as irregular protrusions out of the earth and therefore stood as sites for conflict, transformation, or conversion. Fittingly, Isa 49:1 begins with a call from Yahweh: “coasts and islands, listen to me; distant peoples, pay attention.” The island dwellers are welcome.20 Second, at Cyprus a prominent Gentile, Sergius Paulus, comes to faith. He is an intelligent man and a governing authority, a man of high status (13:7). He is the first named Gentile convert on this mission and a prominent one who has intelligence. Therefore, on Cyprus, Luke shows the gospel message is for the high and low of society, the educated and uneducated.

This point about the gospel being for all is further established by comparing and contrasting this narrative to Paul’s visit to Lystra (14:8–20). Lystra is known as a backwater, rustic, and countryside town. Its inhabitants were known as mountain-dwellers.21 This geographical and cultural reality becomes a key part of the narrative. Paul heals a lame man like Peter did in Jerusalem (14:8–10). The crowd’s response to the healing is quite different from what Peter experienced in Jerusalem, and the geographical location largely explains this divergence. In Acts 3:10 the crowd is filled with awe and astonishment, but here the crowds shout in their own language, “The gods have come down to us in human form” (14:11). This is the only time Luke refers to a local dialect outside of the Pentecost scene.

Those in Lystra think Paul and Barnabas are gods, specifically Zeus and Hermes. Instead of accepting the bulls and wreaths, the apostles tear their clothes and rush into the crowd, explaining to the people they, too, are creatures and not gods. They came not to introduce idolatry, but to destroy it. This is an important point because many critics of Christianity accused the movement of being populated by the uneducated whom the early missionaries had duped. However, Luke shows Paul and Barnabas do not manipulate people. They disclose their true identity and the identity of the one they worship. In Cyprus, a prominent Gentile has been welcomed; in Lystra, Paul and Barnabas have not hoodwinked those off the beaten path.

Philippi is also a significant place Paul visits because he establishes new Messianic-households under the thumb of Rome (16:6–40). Philippi was a Roman colony with many retired Roman soldiers. Although Paul has visited other Roman colonies, this city is highlighted for its close connection to Rome. The emphasis on the Roman nature of this episode is evident by Luke’s word choices. “Colony” is used only here and is itself a Latin loan word (16:12). The chief officials are called stratēgoi (16:20), which is a Greek term for Roman praetors. The police are called rhabdouchoi, which are Roman lictors (16:35). Finally, Paul and Silas speak of themselves as Roman citizens (16:37–38).

These details are not merely to add local color; the narrative is concerned with the mission’s penetration into the Roman world. Philippi is Rome in microcosm. In Philippi two household baptisms are mentioned: Lydia and the jailer. This is the first time since Cornelius that Luke mentions the baptism of households, which shows the success of the mission in Philippi. Lydia becomes a central figure who hosts Paul and his companions. The jailer and his household are also converted. A rich woman and a worker of the state are welcomed. Rome valued the order of households as a microcosm of their state. Luke shows new messianic households are sprouting in the midst of a Roman colony.

If in Philippi Paul confronted Roman customs and in Lystra he challenged rustic pagan practices, then in Athens he clashes with the intellectual elite (17:16–34). Luke presents Paul as a philosopher grounded in the logic of the Hebrew Scriptures as he announces a more universal message to this sophisticated crowd. Though many universalize the Athens speech, making it the training ground for every type of apologetics situation to a non-Christian crowd, the scene in Athens presses into the particular.22 The philosophic crowd are integral to the narrative. Even though Athens was not at its prime, it was still the center of Greek philosophy because of its association with Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle.23 Luke makes sure readers do not miss this point with his mention of the agora, Epicurean and Stoic philosophers, pagan shrines, and the Areopagus.

Paul addresses Athens at their basic assumptions and deploys philosophical language to stake out common ground. Though Paul is labeled an amateur philosopher (17:18), he makes Yahweh known to them through Jesus Christ. Rather than explicitly employing the OT Scriptures to prove Jesus is the Messiah, as he has done at other locales, Paul speaks to them in the philosophic language of the day. He quotes their own poets and alludes to their traditions. However, he does so in order to transform their worldview. The speech is essentially a call to repentance, not a search-and-find game for commonalities.

Paul narrates the incongruity between Jesus’s message and Gentile religion, while at the same time arguing the Christian movement contains the best features of Greek philosophy. It is the superior philosophy. Ultimately the dividing point is Jesus’s resurrection. When they hear Paul speak about the resurrection of the dead, they cut him off and mock him (17:31–32). Even though Paul’s message pulled on certain commonalities, it also fundamentally challenged their social imaginary.

Many bypass this point; a church is birthed in Athens (17:32–34). Some Athenians reject Paul’s message; others are interested in hearing more. A group joins Paul, of which two are named: Dionysius the Areopagite and a woman named Damaris. Contrary to what some argue, Athens is not a failure. Dionysius’s reception shows some from Mars Hill accepted his teaching, and Damaris’s close association with him may indicate Damaris is also a distinguished Areopagite.24 While many groups showed prejudice against women scholars in this time, some communities were more open to female members and Epicureans and Stoics were some of these latter groups.25 This indicates Luke paints Christianity in the same way: women scholars are welcome.

The next narrative displaying the diversity of Gentiles welcomed is Paul’s work in Ephesus (18:24–19:41). Ephesus was known for its magical practices and the Artemis cult. If in Athens Paul takes on the intellectual elite and in Rome he goes to the political head, in Ephesus he engages the center of idolatry, where he proves the forces of darkness and magic cannot overpower the name of Jesus. Luke puts more emphasis on Paul’s extraordinary miracles in this narrative than any other. He even states the handkerchiefs or aprons that touched Paul’s skin were carried away and used as healing conduits (19:11–12).

Then some Jewish exorcists (sons of Sceva) try to employ Paul’s power, but the evil spirits leap upon them and master them (19:13–20). Rather than displaying their power over the spirit, they are overpowered and leave defeated and shamed. The result of this humorous incident is positive for the residents of Ephesus. Many believers confess their practices and burn their books in front of everyone (the equivalent of 50,000 days’ wages). The action signals the defeat of magic by the name of Jesus: “magic has become obsolete…the books are emblems of a defeated regime.”26

The effect is that the word of the Lord flourished and prevailed. Here Luke reports the “growth, strength, and power” of the word (19:20, my translation) rather than “multiplication” as he did in 6:7 and 9:31. This unique word choice confirms the supernatural theme in the Ephesus narrative. It signals victory for the gospel of Jesus and his community. The devil’s terrain shrinks as the Lord’s increases.

The final location Paul goes to is Rome: the heart of the empire. Paul has sparred with the intellectual elite, the city of magic, and the rural towns, and now he comes to the seat of power. While on trial he testifies to kings and governors. Acts 13–28 shows the message of Jesus is available to all. This is further supported because Rome was not the ends of the earth. Rather it is the center of the earth (from a Roman perspective) “with a central milepost from which all the roads of the empire radiated out.”27 Though the forces of nature and the schemes of man try to stop Paul, neither can hinder God’s will to welcome Gentiles.

VI. CONCLUSION

In the prologue to his Gospel, Luke said he was writing an “ordered narrative” about the things that have been fulfilled among them. Sometimes when we examine the OT in the NT, we only study the explicit citations, forgetting that these are placed in a larger story.

I have argued Luke constructed his story of the early church in a way that speaks to his “fulfillment” themes. In Acts 1–7 Israel is restored. Not all Israel responds positively to the message, but God has set apart a remnant for himself. In Acts 8–12 the good news goes to those on the margins. God gathers his outcasts. Finally, in Acts 13–28 the message goes to the ends of the earth. This includes all types of Gentiles: the rich, poor, educated, uneducated, men, women, city-dwellers, and those in the rural areas.

Luke closes Acts by noting that the proclamation of the kingdom of God continued to go forth without hindrance (28:31). Isaiah promised that “instruction will go out of Zion and the word of the LORD from Jerusalem” (Isa 2:3). This promise is fulfilled in Acts, indicating God’s promises cannot be stopped.

- Northrop Frye, The Great Code: The Bible and Literature (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1982), 208. ↩︎

- Brian Rosner, “Acts and Biblical History,” in The Book of Acts in Its First-Century Setting: Volume 1: Ancient Literary Setting (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1993), 65–82. ↩︎

- Though I will place Acts 7 at the end of the first section of Acts, it also functions as a transitional point to Acts 8–12. ↩︎

- Some of the following material is also contained in chapter 6 of my forthcoming book and

used with permission. Patrick Schreiner, The Mission of the Triune God: A Theology of Acts, New Testament Theology (Wheaton: Crossway, 2022). ↩︎ - Luke makes very little mention of Galilee (cf. 9:31). Interpreters differ on why Luke downplays Galilee. Some say it was intentional because Galilee was already Christian land based on Jesus’s ministry. Others assume Luke simply does not know about the mission to Galilee. Kuecker is likely right to point out that in Acts 1:1–11 Jesus’s disciples operate with two layers of social identity: Galilean and Israelite. Aaron J. Kuecker, The Spirit and the “Other”: Social Identity, Ethnicity and Intergroup Reconciliation in Luke-Acts, LNTS 444 (London: T&T Clark, 2011), 98–104. They are a regional subgroup and they are called to go to Jerusalemites, Judeans, Samaritans, and the ends of the earth, all of which involve crossing boundaries. Jesus says the Spirit will come on them and they will be “his witnesses” to the “other,” thus desacralizing and decentering their ethnic identity. This does not mean they lose it, but their mission is to the “other.” ↩︎

- Translations of Scripture are from the Christian Standard Bible. ↩︎

- The ethnic reading is supported both by the allusions to Isaiah and the intertextual connection with Matt 28:19 where Jesus calls his disciples to go out to all “nations” (ethnē). ↩︎

- David W. Pao, Acts and the Isaianic New Exodus (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2016). ↩︎

- This outline largely follows David Seccombe, “The New People of God,” in Witness to the Gospel: The Theology of Acts, eds. I Howard Marshall and David Peterson (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998), 349–72. Both Peter and Paul, the two main figures in Acts, portray this growth in temple terms in their letters (1 Pet 2:5–6; 1 Cor 3:9–17; Eph 2:19–22). ↩︎

- James D. G. Dunn, The Acts of the Apostles (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1996), 1. ↩︎

- This chart is adapted from notes Tim Mackie sent me in a personal email. ↩︎

- F. Scott Spencer, Journeying through Acts: A Literary-Cultural Reading (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1997), 62. ↩︎

- Luke notes that this man’s “ankles become strong.” Some attribute this comment to Luke’s interest in medical terminology, but Mikeal C. Parsons, Acts, Paideia (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2008), 55–56; Parsons, “The Character of the Lame Man in Acts 3–4,” JBL 124, no. 2 (2005): 295–312, argues this should be thought of more in terms of “physiognomy,” which was the association in the ancient world of the outer physical characteristics with inner qualities. Feet and ankles were the object of physiognomic consideration indicating a robust character. ↩︎

- Le Donne rightly argues that in Acts 1–7 the Holy Spirit restores the temple presence of the Lord and that this narrative should be viewed in that light, even though the specific location of Solomon’s Portico is not explicit in this section as it is in 3:11 and 5:12. Anthony Le Donne, “The Improper Temple Offering of Ananias and Sapphira,” NTS 59, no. 3 (2013): 346–64. ↩︎

- The inclusion of “Judea” has confused interpreters. The strongest argument against this structure concerns the linking of Judea and Samaria since Antioch, Syria, Damascus, and Jerusalem are included in 8–12. Mark L. Strauss, The Davidic Messiah in Luke-Acts: The Promise and Its Fulfilment in Lukan Christology, LNTS 110 (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1995), 3–4. However, Luke can use Judea in both a more proper way (the southern district of Palestine distinct from Galilee; 9:31) and a more general way (encompassing all Palestine; 10:37). I take Judea and Samaria as a merism covering that entire region. The two regions are linked grammatically and include the adjectival modifier “all” (kai en pasē tē Ioudaia kai Samareia). Hengel argues it stands for the land of Israel more holistically including what was current Roman Syria. Martin Hengel, “Ioudaia in the Geographical List of Acts 2:9–11 and Syria as ‘Greater Judea,’” BBR 10, no. 2 (2000): 161–80. ↩︎

- Omri, of the Northern Kingdom, ended up building the city of Samaria (1 Kgs 16:24), and it became the capital of the Northern Kingdom as Jerusalem was the capital of the Southern Kingdom. Both the North and the South were exiled, but those who remained in the land intermarried with Canaanites. When the exiled came back, they sought permission from Alexander the Great to build a temple on Mount Gerizim and they had their own form of the Pentateuch. The Samaritans therefore had a different capital, customs, and temple. Bock notes how they were treated as half-breeds; to eat with a Samaritan was said to be like eating pork; their daughters were seen as unclean; and they were accused of aborting fetuses. Darrell L. Bock, Acts, BECNT (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2007), 324. ↩︎

- Parsons, Acts, 124. ↩︎

- The word syntrophos means he was reared with Herod. ↩︎

- Beers has argued Luke portrays God’s people carrying out the mission of the Isaianic servant. The suffering of believers, their non-violent response, and their vindication mirror the servant in Isaiah. Holly Beers, The Followers of Jesus as the “Servant”: Luke’s Model from Isaiah for the Disciples in Luke-Acts, LNTS 535 (London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2016). ↩︎

- Fittingly, Paul’s journeys end with him on the island Malta (Acts 28:1–10). ↩︎

- Strabo says those in Lystra lived in remote “mountain caves” and ate food “unmixed with salt” and were ignorant of the sea (Strabo, Geographica 12.6.5; 14.5.24. See Parsons, Acts, 200.). ↩︎

- Eric. D. Barreto, Jacob D. Myers, and Thelathia Young, In Tongues of Mortals and Angels: A Deconstructive Theology of God-Talk in Acts and Corinthians (New York: Lexington/Fortress, 2019), 45–60. ↩︎

- Cicero, Pro Flacco 26.62. ↩︎

- Keener doubts Damaris is an Areopagite since he thinks Luke would have repeated the title. But the opposite may be the case; he did not need to repeat the title since they are associated together. Craig S. Keener, Acts: An Exegetical Commentary, 4 vols. (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2012-2015), 3:2678–80. Bede says this Dionysius was afterward ordained bishop, governed the church in Corinth, and wrote many volumes. Bede, Commentary on Acts 17.34. ↩︎

- Spencer, Acts, 183–84. ↩︎

- Susan Garrett, The Demise of the Devil: Magic and the Demonic in Luke’s Writings (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1989), 95. ↩︎

- Loveday Alexander, Acts in Its Ancient Literary Context: A Classicist Looks at the Acts of the Apostles, LNTS 298 (London: T&T Clark, 2005), 214. ↩︎