Theology Applied

Southwestern Journal of Theology

Volume 63, No. 1 – Fall 2020

Editor: David S. Dockery

As a young professor at a Christian college on the West Coast of the United States in 1990, I (J. Crider) remember conversations among the faculty and administration concerning the importance of the integration of faith and learning. Throughout my training as a musician up to that first appointment as a faculty member, I studied music education and performance at secular institutions. After years of study, I was eager to experience the freedom to pray in my classroom and model for my students what I hoped would be a Christlike example of a Christian musician. Looking back on thirty years of teaching and ministry, I realize how little I understood about the integration of faith and learning.

In another thirty years, historians will look back on 2020 and see seismic shifts in the educational landscape. Some Christian institutions will have altered or abandoned long-held convictions concerning the necessity of residential learning models, some will have given in to pragmatism, and others will have closed their doors.

How should educators at Christian institutions respond amid the 2020 tsunami of educational change? Does “integration of faith and learning” still work as a framework for Christian education? David S. Dockery and Christopher W. Morgan’s call to pedagogues in faith-based institutions gives us a starting place in creating a model of integration of faith and learning for our current situation. In the work they edited, entitled Christian Higher Education: Faith, Teaching and Learning in the Evangelical Tradition, they urge, “We … want to call for the work of higher education in the days ahead to take place through the lenses of the Nicene tradition that recognizes not only the Holy Trinity but also the transcendent creating, sustaining, and self-disclosing Trinitarian God who has made humans in his image.”1 As Christians in the field of higher education, we would like to propose a model that might help fledgling professors like I was thirty years ago.

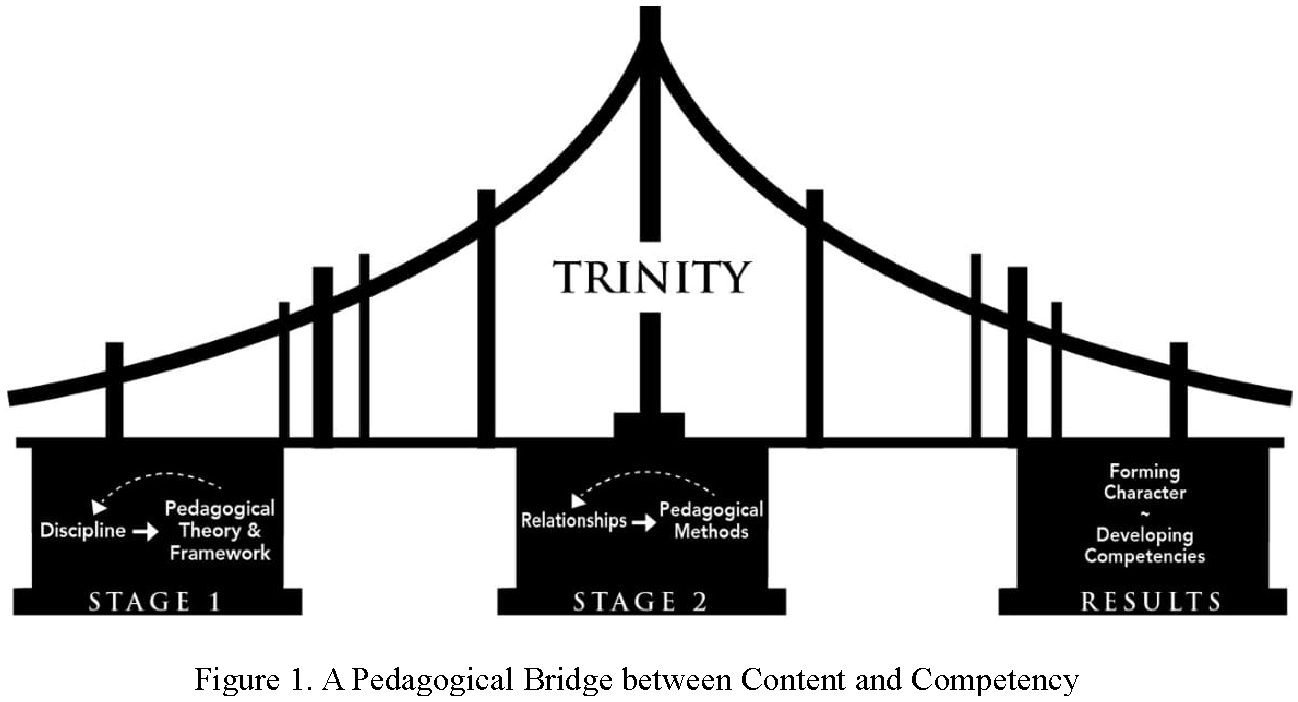

It seems to us that the discussion of Christian higher education’s uniqueness—as juxtaposed with secular education—begins and ends like a bridge spanning a chasm, starting with dedicated Christian faculty members who are experts in their fields and ending with the successful student who demonstrates essential competencies woven within the fabric of Christlike character. What is between the bridge’s endpoints—the bridge’s structure itself—is vital to the thriving success and longevity of Christian higher education. While we all recognize competency and an ever-developing Christian formation in our students as our ideal end goal, clearly articulated pedagogical frameworks and subsequent functional steps in the formation process seem to be less specific (in the current literature) between the discipline expert (Christian professor) and the final product (student).

In other words, while Christian scholars have carefully considered their fields of study through scriptural, doctrinal, and theological lenses, have we as academic disciplers assumed that our own pursuit of the Lord and expertise in our particular fields of study translate into student formation and skill competencies? By introducing this model, we hope to ignite a conversation among Christian faculty that reconsiders how the entire pedagogical process reflects what Dockery refers to as Christian education rooted in the “transcendent creating, sustaining, and self-disclosing Trinitarian God who has made humans in his image.”

Our model includes two stages, each having two parts. In stage 1, professors review perceptions of their fields, rethinking their fields through a Scripture-based understanding. In the second half of stage 1, professors use that new understanding to create trinitarian theories about their disciplines. The dotted arrow back shows that occasionally the new theoretical understanding offers deeper insights into the discipline. On a very basic level, we could consider the return arrows to be modified feedback loops as both parts of each stage continually interact with each other.

The second stage of the model focuses on what happens in the classroom (residential or virtual), starting with relationships. Those relationships impact pedagogical methods we use as Christian educators to ultimately lead to the result—helping form students who are competent in their field of study and maturing in Christlike character.

While the first three elements of the process (the discipline, pedagogical framework, and relationships) can be evaluated for their theological merit, methods are more difficult to assess. For example, is a flipped classroom a Christian method? Is the “bel canto” technique of singing distinctly Christian? However, if pedagogical method choices result from a biblically grounded process, the apologetic for their inclusion in the Christian pedagogy is not based on pragmatism, popularity, or efficiency. Our model is designed to assist educators in evaluating whether they are missing vital connecting points in helping students move from fledgling novices to lifelong learners who are competent in their disciplines and imbued with the character of Christ.

I. STAGE ONE (PART I): DISCIPLINE

Like many others, we struggle with the phrase “integrating faith and learning” because it conveys an unhelpful presupposition that faith and learning are two separate, equal subjects to be spliced together like “art and science” or “botany and philosophy.”2 Scholars through the years have pointed out that in reality faith should drive learning, or what we would call faith-informed learning. As Dockery says, “When we center the work of evangelical higher education on the person and work of the Lord Jesus Christ, we build on the ultimate foundation.”3 The integration of faith and learning movement has highlighted the need for a scriptural lens for each discipline’s research and practice.

Although much excellent work has been accomplished in the area of Christian scholars viewing their disciplines through the lens of Scripture, we have included an example of what we believe is a unifying and systematic approach to how disciplines can be reconsidered through a biblical lens.4 Philosophers Craig Bartholomew and Michael Goheen propose Christian faculty follow the Augustinian tradition of Abraham Kuyper, embracing “the view that redemption involves the recovery of God’s purposes for all of creation and that no area of life … is neutral and exempt from religious presuppositions.”5

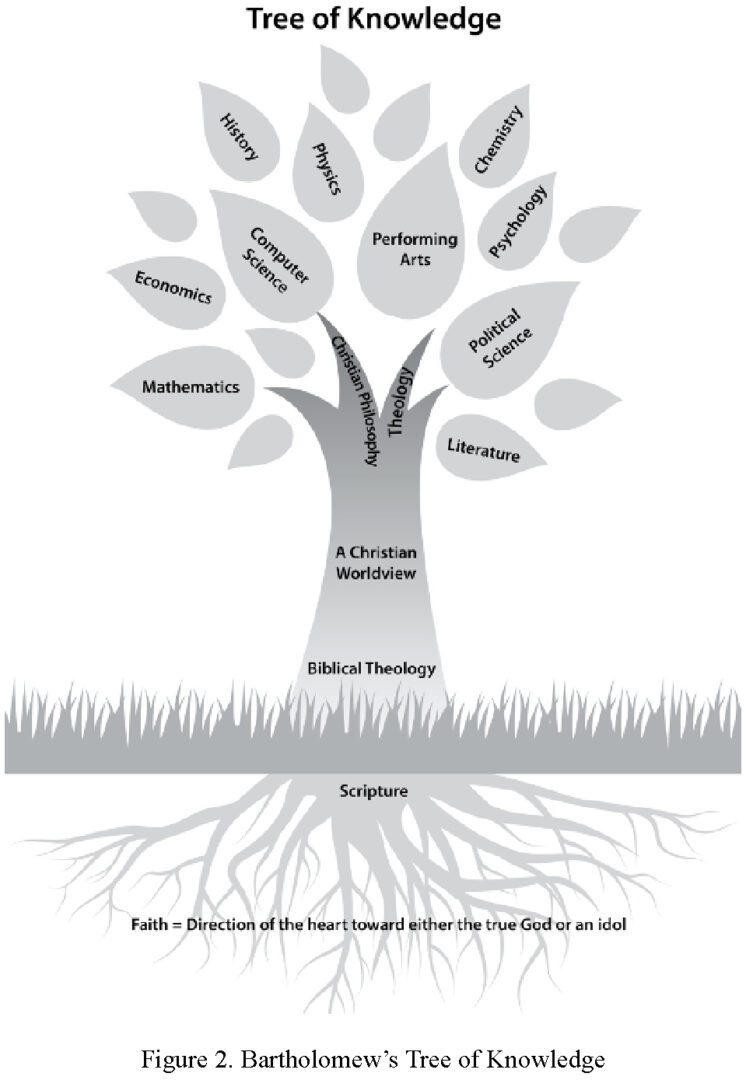

Bartholomew proposes that the Bible sheds its light on all the disciplines and therefore Christian scholars and pedagogues can systematically reconstruct their discipline-specific ontology through a model he calls “The Tree of Knowledge” (see figure 2).6

Bartholomew’s Tree of Knowledge also shows how academic disciplines connect through—

- the shared soil of faith in the authority of Scripture as a common root system

- the united lower trunk of biblical theology (the Bible’s progressive redemptive history)

- the united upper trunk of a Christian worldview. As James Sire articulates in his work, The Universe Next Door, “A worldview … is situated in the self—the central operating chamber of every human being. It is from this heart that all one’s thoughts and actions proceed.”7 Therefore, every pedagogy reflects the worldview of its designer.8

- the two main branches of Christian philosophy and systematic theology. Christian philosophy highlights the reality that a “philosophical scaffolding is always in place when academic construction is being done, even if scholars are not aware of it: always an epistemology is assumed, always some ontology is taken for granted, always some view of the human person is in mind.”9 The twin branch of systematic theology secures a pedagogical curriculum with doctrinal support.10 Kevin Vanhoozer defines doctrine as “direction for discipleship. Doctrines tell us how things are (who God is; what God has done; what the new reality is ‘in Christ’) and urge us to live lives that conform to this (new) reality.”11

The individual branches of respective fields of study all synthesize in what Bartholomew calls an “ecology of Christian scholarship.”12 We contend that as Christian scholars continue to take the necessary steps to anchor their view of their discipline in a model such as Bartholomew and Goheen’s Tree of Knowledge, we will have a significant starting point in advancing Dockery’s charge of “building on the ultimate foundation.” As John Piper relates,

Christian scholarship is not threatened but served when it is permeated by spiritual affections for the glory of God in all things. … Without a spiritual wakefulness to divine purposes and connections in all things, we will not know things for what they truly are … . One might object that the subject matter of psychology or sociology or anthropology or history or physics or chemistry or English or computer science is not about “divine connections and purposes” but simply about natural connections. But that would miss the point: to see reality in the fullness of truth, we must see it in relation to God, who created it, and sustains it, and gives it all its properties, relations, and designs. Therefore, we cannot do Christian scholarship if we have no spiritual sense or taste for God—no captivity to apprehend his glory in the things he has made.13

Now more than ever, Christian institutions have a unique opportunity to articulate with clarity why and how Christian higher education is fundamentally different from a secular education. Conveying with conviction that the moorings of our disciplines are rooted in an unshakable gospel-mediated worldview, we must not patently (and, even worse—unwittingly) adopt secular philosophies as the starting point of our pedagogical engagement.

How can we look more thoroughly and specifically at our disciplines to see them rooted in Christ, the one (as Piper reminds us) “who created it, and sustains it, and gives it all its properties, relations, and designs?” Baptizing our classrooms with a perfunctory prayer is obviously not the epicenter of Christian education. Our disciplines should be developed from the ground up, incorporating the incumbent research while redefining the theological and philosophical foundations. Thus, Christian faculty are tasked with evaluating and re-evaluating our respective fields through the lens of the one who created our discipline in the first place.

II. STAGE ONE (PART II): PEDAGOGICAL THEORY

We can think of truth as being explicit truth (biblical truth, facts), implicit truth (truth suggested by the facts, like “Trinity,” which while not a term used in Scripture is truth revealed by Scripture),14 and conditional truth (what seem to be facts for a current time, place, or situation). When we study our disciplines through biblical lenses, we are revealing explicit truth; when we move to theory, we work to discover implicit truth.

Once we re-vision our disciplines through a model like Bartholomew’s (uncovering explicit truth), scholars are tasked with developing theories (implicit truth) about their fields. Sometimes professors think of their disciplines on the macro level (broad subject matter) and micro levels (specific lecture material) as static bodies of knowledge that never change, but the most effective pedagogues know disciplines are dynamic: scholarship affirms this by adopting assumptions about the field in research. Our pedagogy—the art and science of teaching—should also be dynamic, being informed by the discipline and sometimes informing the discipline. My (A. Crider) experience as a writing professor in multiple English departments may serve as a helpful example of this dynamic phenomenon of the interplay between the discipline and the pedagogical framework.

Several years ago, I became burdened that the writing instruction I was giving students at a Christian college and evangelical seminary was alarmingly similar to the writing pedagogy their counterparts were receiving in secular institutions.

I had added Christian elements to the classroom—examples from Tolkien’s and Lewis’s writing, rhetorical devices in Chesterton’s work, argument structure in Christian scholars’ articles, and other Christian-infused elements typical in evangelical classrooms. But the pedagogical methods I used were ones I learned in graduate school, ones I learned from literature in the composition field, or ones I gained from classroom experience—“what worked.” I am a Christian, teaching in an evangelical institution, but trained in a secular school. Alvin Plantinga points out the fundamental problem of Christian scholars who train in secular schools and then teach and research at Christian institutions: “[Secularly trained Christian scholars] continue to think about and work on … topics [deemed important to the field]. And it is natural, furthermore, for [a secularly trained Christian scholar] to work on them in the way she was taught to, thinking about them in the light of the assumptions made by her mentors and in terms of currently accepted ideas.”15 Recognizing that theology informs our philosophy, which informs our pedagogy, I wondered if a thoroughly Christian theory of teaching writing was available or even possible. Wolterstorff urges, “Christian scholarship will be a poor and paltry thing, worth little attention, until the Christian scholar, under the control of his authentic commitment, devises theories that lead to promising, interesting, fruitful, challenging lines of research.”16

I began asking colleagues, writers, and theologians this question: “Can writing be taught from a distinctly Christian perspective?” Over and over the answer was the same: “Since you’re teaching at a Christian school, using Christian ideas in your classes, and encouraging students to write content that is Christian, you’re teaching writing from a Christian perspective. That’s all you can do.” When books on integration of faith and learning include chapters on the disciplines, they typically have a chapter on the humanities, communication, or literature, but not on composition, the teaching of writing.

I met a conference speaker whose job at a large Christian university was helping the faculty in all the disciplines integrate faith with learning. I asked him my question—how can writing be taught from a distinctly Christian perspective? He answered, “It can’t. Writing is a skill. Leave the melding of Christian ideas and scholarship to professors in content areas.”

It is difficult to read Plantiga, Marsden, Bartholomew, Vanhoozer, and Dockery; to know God’s preeminent medium for communicating truth is the written Word; and to be told my field is outside the realm of the intersection of faith and learning. As is true of many of us in academia, being told something cannot be done is like a case of poison ivy with its irresistible itch.

Eight months later, I proposed a model for writing professors. After working through Bartholomew’s Tree of Knowledge to explore explicit truth in composition, I used Kevin Vanhoozer’s Trinitarian Theology of Communication to propose implicit truth about how Christian writers can write (and teach writing) from a Trinitarian-based model that guides student writers from theological formation to methodological practice (see figure 3).17

While the model gave me a way of explaining how my students and I could approach writing Christianly and seemed to increase students’ motivation to write, Joe also saw in the model transdisciplinary potential for his music students.

As a musician, I (J. Crider) can see immediate impact in helping young musicians interact with the music/composer and audience on a Trinitarian level they have perhaps never before considered, and at the same time, give students a lens to see how the music helps mature them as artists and Christians. When professors develop theologically-rooted pedagogical theories, they are one step closer to helping students bridge the chasm between the starting point (body of knowledge in the discipline) and the goal (a competent Christ-filled graduate).

Although my model helped my students and me (A. Crider), my theoretical framework still lacked feet. I could help my students see the field from a Christian perspective and give them a theoretical model, but as with a case of poison ivy, my questions were “calamined,” not cured, because my theory did not specifically produce the pragmatic solutions I was looking for in the classroom.

Looking back on my study, I am still asking the following question: “How can pedagogical theory impact what happens in the classroom?” However, what I have learned through the process of developing a pedagogical framework is that all teachers (myself included) model their teaching and their classrooms on some kind of pedagogical theory or framework. The exercise of developing a writing pedagogy rooted in the Trinity forced me to be intentional about grounding my concept of teaching writing in something much more important than the secular pedagogies I had learned and practiced.

III. STAGE TWO (PART I): RELATIONSHIPS

So how can scholars in any field move from a scriptural lens for their discipline and pedagogical theory to classroom application? If the goal of Christian higher education is student formation and student competency, an academic course’s content is a necessary but insufficient vehicle for change because the working out of truth happens in relationship.18 Education does not occur when students merely think rightly about something. Character formation and competency rely on pedagogy that includes right content and right relationships in the classroom (whether the classroom is on campus or online).

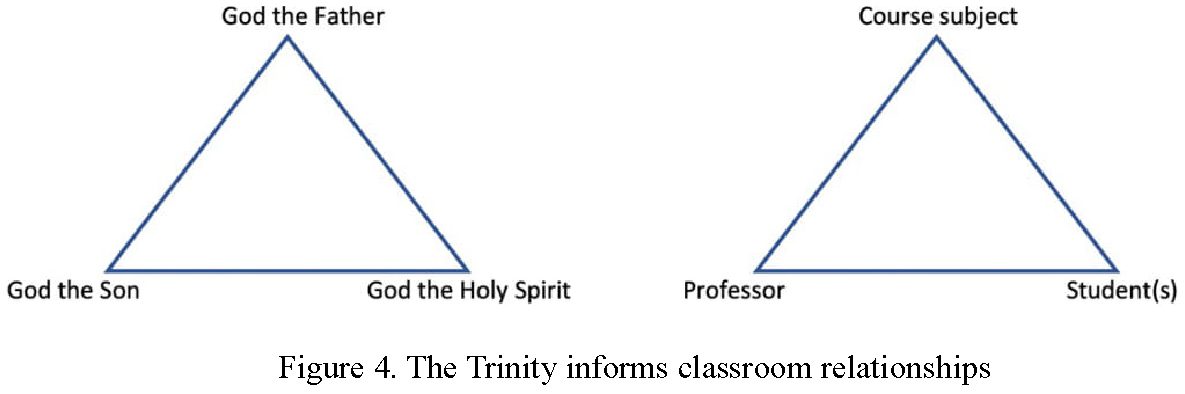

The root of all relationships is the Trinity. Salvation is based on relationship. Sanctification is a process built on relationship. Even at the discipline level, pedagogy is relationally motivated, as is evidenced in a Christian professor’s “calling” to their subject area and to Christian education. Relationships within the Christian classroom link the professor’s scripturally based understanding of the discipline and the subsequent pedagogical framework with teaching methods.

As God was before all things, the first relationship, the ultimate relationship, is the Trinity. We live and move and teach within the reality of the biblical metanarrative, created, directed, and sustained by the Trinity, so formation and learning in the classroom should also reflect the Trinity.19

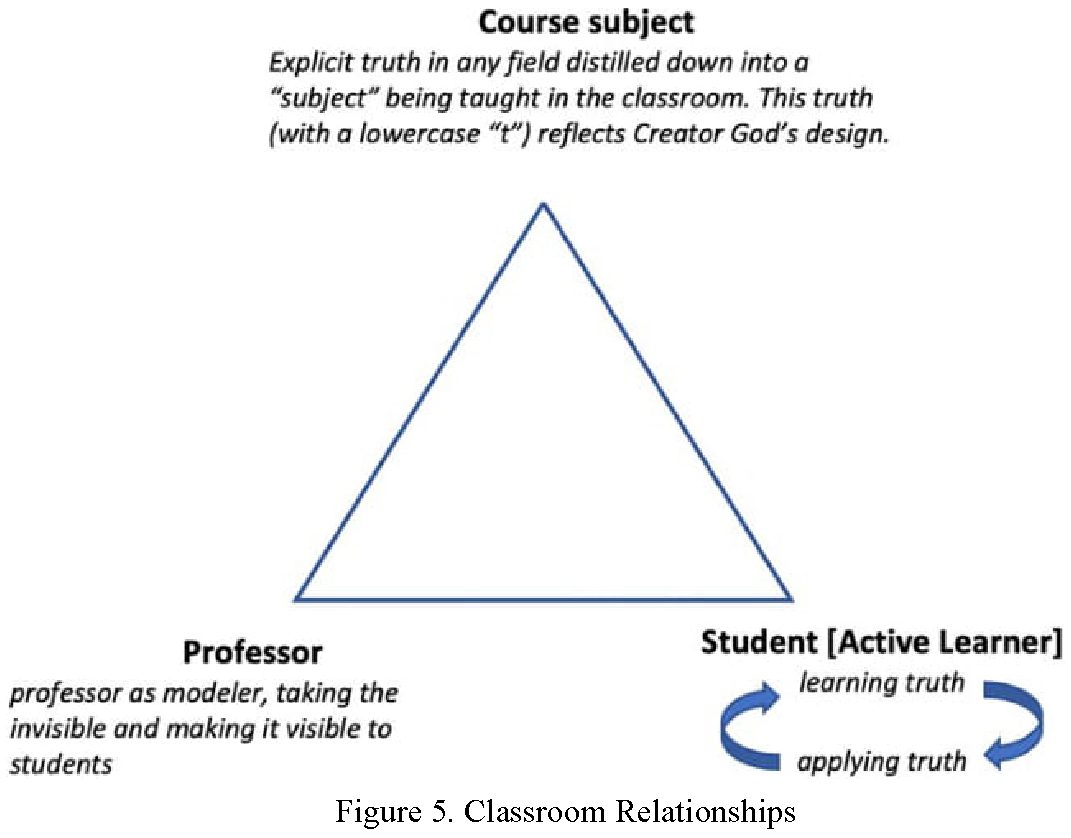

In the higher education classroom, at least three types of relationships exist: (1) the course subject/discipline (including the discipline interacting with other subjects and disciplines), (2) the professor, and (3) the student (including students with other students). When we agree that the Trinity informs relationships in the classroom, we are not implying a perfect correlative relationship of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit to discipline, student, and teacher. But teachers and students are created in His image, in His likeness, and our imago Dei is visible in relationships and in some ways reflective of Trinitarian roles.

As Christian educators consider their role, the student role, and the role of the subject or discipline in this triadic relationship, the words of Carl R. Trueman resonate: “Everything the believer is and everything the believer does has to be understood at some level in trinitarian terms.”20 A more intentional awareness of the Trinity may help us re-envision classroom dynamics.

One way to re-envision classroom dynamics among the course subject, professor, and student is to consider the model of Trinitarian relationships. The Father’s “purpose in creation,” the Son’s incarnation, and the Holy Spirit’s active indwelling give significance to the triadic subject-professor-student relationship. 21

1. Discipline/Course Subject. While we have discussed the importance of viewing our discipline through the lens of Scripture, we also need to see our course subject matter in light of the Trinity. The course subject is “truth,” God’s design of how things work in creation. As mentioned earlier, truth includes explicit truth (biblical truth), implicit truth (revealed truth deduced from explicit truth or uncovered through general revelation), and conditional truth (things that tend to be true). In other words, truth in any field distilled into a course subject taught in the classroom is truth (with a lowercase “t”) and reflects Creator God’s design: Christian scholarship should (1) “bring to light the hidden things of God,” (2) “give us joy in digging up the gold hidden in creation,” and (3) “contribute to the well-being of human life” (serve other people through our learning).22 For all of us laboring in Christian education, the content of our subject matter embodies the overall competencies we want our students to develop, ultimately as an act of worship. For the student writer and student musician, their work creating discipline-specific artifacts are acts of worship—doxological writing and doxological performance. The finished artifacts (a writing assignment and a recital) echo not only a reflection of God’s truth displayed in the work of the student, but also the student’s realization and understanding of the truths they have learned in the process.

2. Professors. Martin Luther saw education as giving access to knowledge, but today information is easily googled, so dispensing information is no longer a professor’s primary function. Instead, just as the Son’s incarnation revealed the Father, the professor makes the invisible visible, making the discipline through the course subject visible for students. As John Frame articulates in his Systematic Theology, “God’s glory, as a divine attribute, is related to his visibility. … So we bring God’s glorious reputation to the eyes of others.”23 Essentially, professors image forth a vision of the discipline for students to capture and actively apply.24

The professor is the modeler of the truth in both character and competency. As Donald C. Guthrie shares, “Delighted teaching for the Christian is collaborative investigation leading to practiced wisdom under the triune God’s care for the sake of others.”25 Guthrie lands on a significant concept of effective pedagogy as he prioritizes collaboration between the professor and the student. While we understand the financial efficiencies of large lecture halls and the professor-as-lecturer paradigm, we also live in a time of MOOCs, where learners can access most courses taught by famous scholars for free. The dynamic core that renders Christian education extraordinary is a professor who not only models character and competency but also fosters a relational culture in the classroom that gives students a vision of what their future might look like. In pedagogical settings like these, students are not simply motivated to memorize facts for a test; instead, they ask questions like:

(1) “How can we create something new with what we’re learning?”

(2) “How does our knowledge of this subject contribute to human flourishing?”

(3) “What does this reflect about God?”

The students then become the convincers to others as Christian practitioners in the field.

3. Students. Similarly, in developing student competency, a Christian understanding of our disciplines and Trinitarian-informed theories (Stage One of the model) is not enough. As James teaches in his epistle, knowing and doing need one another; neither is authentic nor complete without the other.26 Academia, of course, also recognizes the importance of the duo working together. For example, according to Arthur Holmes, learning is both content learned and human activity (experience).27

As we consider the role of the student in light of the Trinity, we see the dynamic function of the Holy Spirit as that of the indweller and ever-active member of the Godhead. As Letham articulates in his work on the Holy Spirit, “The New Testament portrays the Holy Spirit as active at every stage of redemption,” and “the Holy Spirit’s presence is known by what He does.”28 If students could begin to get a vision for their active role in the learning process, rather than being passive receptors of information, transformative learning would take significant leaps forward.

The knowing-doing dyad is well embodied in the active learning pedagogy, which has garnered much attention in recent decades as faculty and administrators seek to help students gain more from the material. Within the Christian higher-education context, however, students must not only know the truth but walk truthfully. The classroom is a potential arena for students to learn truth and engage in truth. When engaging from a true worldview, enactment of the material not only reinforces the content, it shapes the character and behavior of the student. Within this context, faculty serve as guides and coaches to students as they exert personal agency in their learning process. With action comes greater opportunity for students to develop valuable characteristics and behaviors, such as resilience and critical thinking.

IV. STAGE TWO (PART II): PEDAGOGICAL METHODS

For much of the existence of higher education, what we teach has been central to the mission. As higher education continued to secularize, content became the chief distinction between Christian and secular education. However, as our collective understanding of learning theories improves, we know a direct connection exists between how something is taught and what is learned. Therefore, pedagogy is critical, not just the content; the how impacts the what, which subsequently impacts actual outcomes. The epistemological core is explicit, but the methods are conditional.

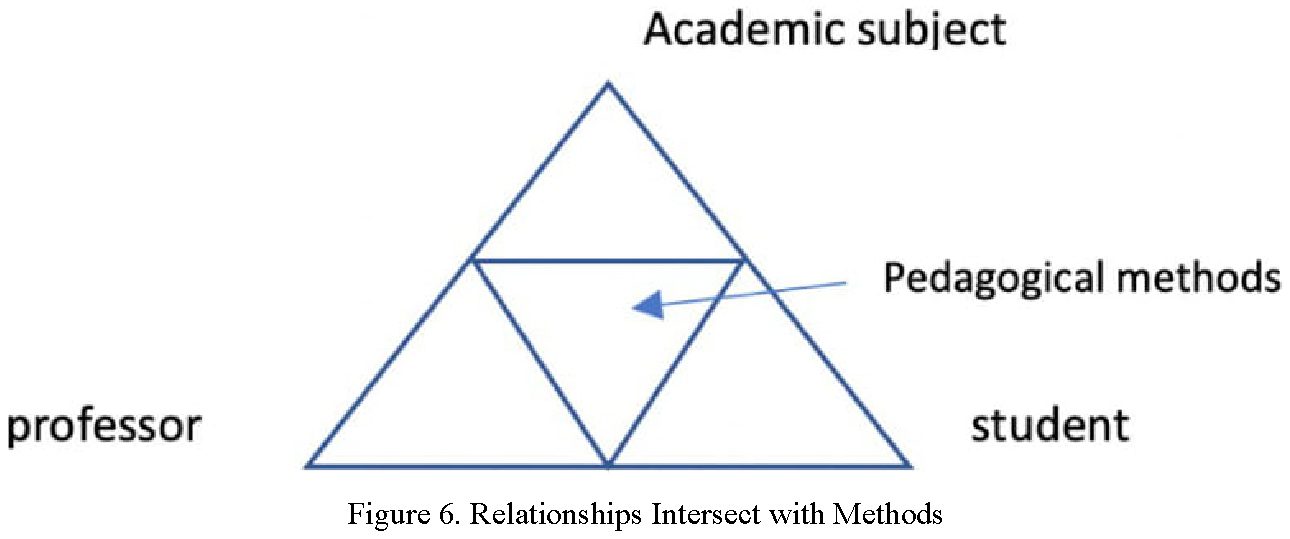

In the previous section we looked at the three major relationships in the classroom (subject, professor, student). The three of those intersect through pedagogical methods—how we teach (see figure 6).

If Christian educators can develop a systematic method of aligning a discipline’s explicit truth (Stage One/Part I content), implicit truth (Stage One/Part II theories), and classroom relationships (Stage Two/ Part I), then teaching methods should be the next domino impacted.

Some self-reflection among those of us who are Christian educators might be necessary as we consider our actual teaching methods. Are we baptizing secular educational practices, or under the guidance and direction of the Holy Spirit are we creating new and better methodologies? It is difficult for us to break from methodological practices that proved effective when we were students because we typically get stuck in the methodological lanes in which we were trained. Yet sometimes those lanes may be like those on the Roosevelt Bridge in Stuart, Florida. The six lanes carried local residents and travelers over the St. Lucie River for decades. But recently, large cracks appeared and concrete fell from the bridge. A new route or reconstructed bridge across the river is necessary, just as we sometimes need to construct new pedagogical paths or reconstruct old ones. We want to encourage effective and creative new ways for information transfer to lead to life transformation and competency.

The purpose of this section is not to dictate a one-size-fits-all pedagogy but to list some questions about pedagogical methods that, when answered, might spark greater results in Christian classrooms. As Guthrie encourages, “Regularly revisiting assumptions about teaching and learning invites consideration of our simplest choices as well as our deepest convictions.”29

Several Questions for Dialogue:

- One way we might reconsider our pedagogy is to think through the kinds of artifacts students should produce, demonstrating their ability to apply, analyze, evaluate, and create because of the course.30 In some courses, artifacts are more concrete, visible indicators of student achievement—worship students design orders of worship and lead them; musicians perform recitals; entrepreneurial students produce new products and services. In other courses, intellectual artifacts are needed; for example, students write papers to demonstrate analysis, synthesis, or creation of new ideas. Do we get trapped into common assessment measures instead of having students produce meaningful artifacts? What artifacts could we have students produce? When a student is in a church history course, what do we want her to be able to do with that history? Is it possible for us to encourage students to assess how their study has changed them?

- Earlier in this article, we objected to the phrase “integration of faith and learning,” preferring faith-informed learning. But perhaps, as the proposed model shows, it is also learning-informed faith, not adding to biblical truth, but reveling in a glorious God who reveals Himself, in part, through our disciplines. As both we and our students learn together and from each other in the classroom, new knowledge increases our appreciation of God and our awe of Him. We see with fresh eyes God’s design in creation. How can we facilitate faith-informed learning and learning-informed faith?

- Pedagogy is our means of discipleship in the classroom, of training students to follow Christ. Are our Christian classrooms more effective than secular ones? How can we measure Christian education’s success?

- How can we develop creative new ways for informational transfer to lead to life transformation and competency? In other words, how do we redesign our pedagogies to more closely embrace explicit biblical truth and use it to help us be more creative, more innovative in relationships and methods (Stage Two)? Do we need a theology of creativity to apply to pedagogy? Is it possible that as the Reformers did not see themselves as innovators but instead saw themselves as recovering the past, so too we can “preserve and pass on the Christian tradition while encouraging honest intellectual inquiry”?31

- For each of our disciplines, do we need a theology of pedagogy? If so, what would it look like?

- How do we develop or evaluate pedagogical models that embrace the absolutes of a Christian worldview while incorporating student uniqueness? Is it possible for our pedagogies to be flexible, personalized, and contextual?

- In our current educational culture of delivering instruction in a worldwide pandemic (COVID-19), we are all asking what the future of education looks like. Yet, there will always be tension between market-driven forces and the need to existentially “flex” as Simon Sinek articulates in his book for business leaders.32 But when existential flexing erodes or eradicates the mission of the institution, the purpose for Christian education suffers. What is the ultimate tip of the spear for Christian education? The local church. If we allow the market to drive our curriculum and delivery models, in the end, will the church be the one that suffers the most?

V. CONCLUSION

As educators fully committed to Christ, his Word, and his gospel, we affirm and sign our institution’s confessional documents verifying our orthodox doctrinal positions that warrant our place on the faculty roster. And for most of us, a significant part of our calling is a desire to train, influence, and disciple the next generation of Christ-following educators and professionals. We understand the starting line (our disciplines in light of a biblical worldview) and the destination (students competent in their fields and growing in Christlikeness), but do we realize the vital nature of the pedagogical bridge that connects the starting line and destination? Have we given careful attention to our own functional pedagogical frameworks, the intentional development of Triune-based relationships, and pedagogical methods? If ever there was a time in the rich history of Christian higher education when professors needed to build Holy Spirit-guided pedagogical bridges between our disciplines and our students, the time is now.

- David S. Dockery, “Christian Higher Education: An Introduction,” in Christian Higher Education: Faith, Teaching, and Learning in the Evangelical Tradition (eds., David S. Dockery and Christopher W. Morgan; Wheaton: Crossway, 2018), 26. ↩︎

- Laurie Matthias traces the use of the phrase “integration of faith and learning” and points out the concept may be worn out and even rejected by some, but the “phrase persists nonetheless.” Laurie R. Matthias, “Faith and Learning,” in Christian Higher Education, 172. ↩︎

- Dockery, “Christian Higher Education,” 27. ↩︎

- A few examples of scholars using a scriptural lens through which to view their disciplines include

Harold M. Best, Music Through the Eyes of Faith (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1993); Jeremy S. Begbie, Resounding Truth: Christian Wisdom in the World of Music (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2007); John C. Polkinghorne, The Faith of a Physicist: Reflections of a Bottom-up Thinker: The Gifford Lectures for 1993-4 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994); Francis S. Collins, The Language of God: A Scientist Presents Evidence for Belief (New York: Free Press, 2006). ↩︎ - Craig G. Bartholomew and Michael W. Goheen, Christian Philosophy: A Systematic and Narrative Introduction (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2013), 24. ↩︎

- Craig G. Bartholomew writes about his Tree of Knowledge in Introducing Biblical Hermeneutics: A Comprehensive Framework for Hearing God in Scripture (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2015), 474-75. The Tree of Knowledge figure is from Amy L. Crider, “A New Freshman Composition Pedagogy for Christian Colleges and Universities” (Ed.D. thesis, Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, 2017). ↩︎

- James W. Sire, The Universe Next Door: A Basic Worldview Catalog, 5th ed. (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2009), 20. ↩︎

- George Guthrie asserts, “Whether a person approaches research as a pragmatist, hedonist, naturalist, behaviorist, Marxist, Christian, or one with no readily identifiable worldview, presuppositions are in place and have a profound effect on the way one thinks about research and conclusions.” George H. Guthrie, “The Authority of Scripture,” in Shaping a Christian Worldview: The Foundation of Christian Higher Education (eds. David S. Dockery and Gregory Alan Thornbury; Nashville: B&H, 2002), 21. ↩︎

- Bartholomew, Introducing Biblical Hermeneutics, 216. ↩︎

- See Crider, “New Freshman Composition Pedagogy,” for a thorough discussion of each section

of the Tree of Knowledge as related to developing a Christian writing pedagogy. ↩︎ - Kevin Vanhoozer, note to A. Crider, 2017. ↩︎

- How I (J. Crider) wish I would have been more aware of Scripture’s synthesizing authority in

uniting seemingly disparate disciplines thirty years ago. Even in theological seminaries, major areas of study have been (and often still are) siloed into discipline-specific camps. For years, church musicians rarely engaged with theologians until relatively recently when we finally fig- ured out that church musicians need to be theologians. ↩︎ - John Piper Think: The Life of the Mind and the Love of God (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2010), 168-69. ↩︎

- Theories (fledgling facts under scrutiny) fit in this category also. ↩︎

- Alvin Plantinga, “Advice to Christian Philosophers,” Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers 1, no. 3 (July 1984): 255. ↩︎

- Nicholas Wolterstorff, Reason within the Bounds of Religion, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1976), 106. ↩︎

- Crider, “A New Freshman Composition Pedagogy,” 48; Kevin J. Vanhoozer, Is There a Meaning in This Text? The Bible, The Reader, and the Morality of Literary Knowledge (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1998), 161, 456. See also Michael Reeves, Delighting in the Trinity: An Introduction to the Christian Faith (Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 2012), 457. ↩︎

- See Donald C. Guthrie, “Faith and Teaching,” in Christian Higher Education, 149-67. ↩︎

- Dockery uses the description “creating, sustaining, and self-disclosing Trinitarian God.” Dockery, “Christian Higher Education,” 26. Scott Swain articulates, “All things are from the Trinity, through the Trinity, and to the Trinity.” Scott R. Swain, “The Mystery of the Trinity,” in The Essential Trinity: New Testament Foundations and Practical Relevance (ed. Brandon D. Crowe and Carl R. Trueman; Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R, 2017), 213. ↩︎

- Carl R. Trueman, “The Trinity and Prayer,” The Essential Trinity, 222. ↩︎

- “Not only does the doctrine of the Trinity identify God; it also illumines all of God’s works,

enabling us to perceive more clearly the wonders of the Father’s purpose in creation, of Christ’s incarnation, and of the Spirit’s indwelling.” Scott R. Swain, “The Mystery of the Trinity,” 213. ↩︎ - Craig G. Bartholomew, Contours of the Kuyperian Tradition: A Systematic Introduction (Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2017), 298. ↩︎

- John Frame, Systematic Theology: An Introduction to Christian Belief (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R. 2013), 396. ↩︎

- Frame, Systematic Theology, 396-98. ↩︎

- Guthrie, “Faith and Teaching,” 159. ↩︎

- James 1:22-25. ↩︎

- Arthur F. Holmes, “What about Student Integration?” Journal of Research on Christian Education

3, no. 1 (Spring 1994): 3–5. ↩︎ - Robert Letham, The Holy Trinity: In Scripture, History, Theology, and Worship (Philipsburg, NJ: P&R, 2004), 56-57. ↩︎

- Guthrie, “Faith and Teaching,” 152. ↩︎

- Bloom’s Taxonomy. ↩︎

- Dockery, “Christian Higher Education,” 27. ↩︎

- Simon Sinek, The Infinite Game (New York: Portfolio/Penguin, 2019), 181-95. ↩︎