Scripture, Culture, and Missions

Southwestern Journal of Theology

Volume 55, No. 1 – Fall 2012

Managing Editor: Terry L. Wilder

We live in a period of transition, on the borderline between a paradigm that no longer satisfies and one that is, to a large extent, still amorphous and opaque A crucial notion in this regard [i.e., the emerging paradigm of a postmodern theology or missiology] will be that of creative tension: it is only within the force field of apparent opposites that we shall begin to approximate a way of theologizing for our own time in a meaningful way.1

We are under great pressure to adapt the Gospel to its cultural surroundings. While there is a legitimate concern for contextualization, what most often happens in these cases is an outright capitulation of the Gospel to the principles of that culture.2

Introduction

When societies, cultures, and civilizations collide in eras of escalating chaotic change on a clearly globalized scale, then confusion and doubt to some extent arise as humanity feels for a way forward. Twenty years ago, David J. Bosch spoke to the tensions that would be the path of missions future. What Bosch called a “creative tension” has now become a bold instability that threatens the core of biblically defined faith and has shifted balance to the predispositions of a secular and ever secularizing mix of cultures that are dominant in the processes of gospel contextualization.

In more recent years, Edward Rommen observes the shift and calls it “outright capitulation.” When Bosch and others parsed out the truth crises at the end of the twentieth century, Bosch advocated a moderating point between the polar pulls of absolutism, on the one hand, and relativism on the other.3 He expressed concern over the potential of “an uncritical celebration of an infinite number of contextual and often mutually exclusive theologies. This danger—the danger of relativism—is present.”4

Such tense balance, now slipped over into imbalance, gives human experiences and contexts priority when discerning whether the Bible or culture should hold sway over our faith and practice. Herein lay the need for a reflection on the relationship between culture and Scripture. At present, it seems, sola cultura holds sway. Yet, we ask, how can one move back to the Reformation’s now distant echo of sola scriptura and regain the prophetic and countercultural voice of scripture that led Luther and others to throw off the yoke of rival truth systems? Or should believers in this postmodern world even wish to try? The aims of this article are to describe the tensions between text and culture, explain how the role of culture has come to have sway in the conversation, and to propose a set of biblical principles to take the lead in the contextualization dance between text and context. The latter is done against the backdrop of an anthropological model for understanding religious and social change dynamics and notes future trajectories that appear available to evangelicals in general and Southern Baptists in particular.

Text-Context Tensions in Doing Theology

It is hard to imagine the degree to which the rush of postmodern thought engulfs us with radically different modes or frameworks for thought, consequently altering the collective Western mind. Who would have thought that barely a generation ago words and syntax of speech were so vastly different and would change so quickly? Now “bad” means “good” (thanks to Michael Jackson), “good” means “bad” (thanks to Madonna), and “friend” is a verb (thanks to Facebook)!

Syntax changes reflect shifts of thought processes, and these both expose and reshape core philosophical and worldview thought simultaneously. Such dynamic processes converge and challenge or alter theological reflection and assumptions because they do not happen in a vacuum. Shifts rework our systemic thought to such an extent that now a horizontal rather than a vertical direction for revelation transpires. Does God speak to humans and consequently they are to be “doers of the Word?” Or is it more appropriate to conclude that there is loss of the biblical metanarrative, an overarching view of God’s word being similar to an “Archimedian point” that defines theological thought? Is it that humans set out to discover and reflect on theology horizontally? If so, there is a genuine probability that our search will result in humans preferring to be “hearers of the Word only.”

Systemic worldview “make-overs” shove theology’s orthopraxis primarily, if not exclusively, to the horizontal plane as well because of the “constant awareness of the limitations of human perception, including our theological perception of God’s revelation.”5 The church at large, therefore, “should always be aimed at actively and creatively challenging the whole of society and its institutions to deal with the values of the reign of God.”6 There is little doubt that the gospel includes a horizontal dimension. The Great Commission issues imperatives to “Go . . . make disciples . . . baptize . . . and teach.” Epistemological skepticism, and relativism its partner, redirect the source of revelation from either its general or special forms to a search process designed to discover mission where God supposedly speaks today. Gustavo Gutiérrez, the father of Liberation Theology, merely decades ago reflected this same set of assumptions when he concluded that a freeing theology is “not so much a new theme for reflection as a new way to do theology [This theology] tries to be part of the process through which the world is transformed. It is a theology which is open—in the protest against trampled human dignity, in the struggle against the plunder of the vast majority of humankind, in liberating love, and in the building of a new, just, and comradely society—to the gift of the Kingdom of God.”7

Vertical and horizontal tensions, or the contrasts between text and context, are not new. H. Richard Niebuhr skillfully identifies theological patterns that deal with these realities down through the church’s history in his now classic book, Christ and Culture. His prioritization of relativism (and of the absolute secondarily) is clearly seen when he describes responsible theologians as those that

can accept their relativities with faith in the infinite Absolute to whom all their relative views, values and duties are subject. . . . They will then in their fragmentary knowledge be able to state with conviction that they have seen and heard, the truth for them; but they will not contend that it is the whole truth and nothing but the truth, and they will not become dogmatists unwilling to seek out what other men have seen and heard of that same object they have fragmentarily known. Every man looking upon the same Jesus Christ in faith will make his statement of what Christ is to him; but he will not confound his relative statement with the absolute Christ.8

So, are these the only two choices: horizontal relativism or vertical absolutism? D. A. Carson revisits this set of tensions and critiques both polar opposites. While not surrendering inerrancy and maintaining a high degree of theological certainty, he advocates a “modest modernism” and a “chastened postmodernism.”9 Further, he confirms that truth seeking humans, “can know, even if we cannot know [truth] exhaustively or perfectly but only from our own perspective.”10 For Scripture’s prophetic voice to be heard, the directional priority should flow from God’s Word to humanity with an increasingly closer approximation to God’s truth. Its signature effect is an increasingly apparent life-evident walk by the believer in a manner worthy of his calling. Transformation into the likeness of Christ should be the gradual outcome.

Elsewhere Carson outlines and affirms the idea of a hermeneutical spiral that enables truth seekers to grow by rightly dividing God’s truth.11 This spiral dynamic takes the Bible seriously, as what it claims to be, while recognizing the foibles of human reason. Yet humans pose existential questions to the text with listening hearts, and recognize God’s revelation of himself by and in the text. Then, we anticipate the Spirit of God’s ministry impact to convict and transform life. Is one’s illumination of the Spirit exhaustive in that single moment? Paul says that there is a “renewing” of our minds, indicating a process for growing into a genuine knowing, being, and doing. Further questions posed throughout a lifetime to the text, under the lordship of Christ and the renewing effects of the Holy Spirit, spur on the sanctifying and transforming influence brought to bear upon believers in Christ. Sanctification is always spiraling and conforming ever more closely to the image of Christ.

Postmodernism’s influence in and among evangelical believers is changing our perceptions of all this. The thoughts of Niebuhr and others of his ilk are indeed being revived, even if inadvertently. Reader-response interpretations are based on the assumption that human understanding is so limited that God’s Word cannot or does not address believers in ways that transform the hearer. Instead, the exchange between God and mankind takes on a mutual mixing of ideas and synthesizes them into something neither the biblical context nor modern ones may reflect. Simply stated, reshaping is bidirectional. God’s Word reshapes believers and simultaneously believers reshape God’s Word into something relevant to and fit for emergent or emerging postmodern cultural contexts.

For example, Craig Van Gelder utilizes this methodology to address and suggest ways to reformat biblical ecclesiology. He writes, “the specifics of any ecclesiology are a translation of the biblical perspective for a particular context. New contexts require new expressions for understanding the church. . . . The church has the inherent ability to translate the eternal truths of God into relevant cultural forms within any context. In missiology circles this process is referred to as contextualization.”12 Notice the translational model for contextualization evident in Van Gelder’s theological method that illustrates the opinions of numerous Emerging Church Movement advocates. There is no guiding element designed to avoid precisely what Bosch, as noted above, foresaw could happen, namely, the development of “an infinite number of contextual and often mutually exclusive theologies.”13

Karen Ward, another Emergent Church voice, uses the metaphor of swapping cooking “recipes” to illustrate how emergents prefer to “do theology.” Specifically, she demonstrates this technique in regard to the atonement, stating that “we are looking for nonpropositional ways of coming to understand the atonement, ways that involve art, ritual, community, etc. . . . So we’ll enter into the dialectic of Christian dogmatics, but with a grain of salt, knowing that if we get saved in virtue of our correct theology, we’re all in trouble.”14 Ward demonstrates the cautious concern of the present article. If Scripture is sometimes narrative but primarily teaches and instructs with propositional truth precepts, which reading it demonstrates, then why do emergents resist propositional truth so strongly when it is clearly in the Bible? By way of analogy from the field of art appreciation, we ask, Is the Bible a representational or an abstract art form, surreal or real? If it is what it purports to be, then Scripture speaks and humans should listen. In parallel, is theology more a didactic or dialectic process—proclamation or translation? Consequently, is Scripture or culture primary i n ongoing contextualization?

Succinctly stated, postmodern skepticism + emergent sociological discontent + rising religious pluralism + relativism = plural localized theologies so determined by local contexts as to overpower the sound of God’s prophetic voice in the Bible, making for highly individualized designer theologies. Alan Hirsch, another emergent voice, pointedly expresses his apprehensions regarding this result and says he has observed how some emerging churches eventually die off because of this inherent danger. He warns that the “emerging church” is “very susceptible to the postmodern blend of religious pluralism and philosophical relativism. This makes it very hard to stand for issues of truth in the public sphere.”15 The old adage is likely true: when a person does not stand for something, then he will probably fall for anything. Are there other dynamics to note in trying to determine how to move forward from this contemporary theological quagmire?

Cultural Change Dynamics

Patterns of religious change and the social phenomena they spawn are well documented. In one way it is as old as humanity itself. Even in the garden people preferred to adapt God’s Word to their own liking. Drawing upon the perspective of cultural anthropologists regarding these social tendencies is helpful to track some of our current theological shifts. Anthropological observation and documentation of how new religious ideas affect cultures, particularly among peoples of the world that are less connected to the larger world, are now well over a century old. When core values change in a society, cultural worldviews follow suit and eventually shift, often in several directions. When sudden and sometimes disturbing change transpires from outside cultural pressure, “people recognize that they are in the process of being stripped of their own culture, but they have not been assimilated into the dominant culture.”16 As this dynamic unfolds, mechanisms of cultural revitalization activate, and typically a “charismatic leader or prophet who has a vision” emerges with ideas for forward momentum.17

One example of cultural revitalization is the phenomenon of a “cargo cult.” During WW II, South Pacific military campaigns transpired in and around indigenous island peoples. The outsiders came and went, but they left behind the wreckage of war, trinkets of modern life, and these items were a source of genuine curiosity to the islanders. When the strangers departed, the islanders invoked ancestral spirits for assistance in bringing the cargo bearers back.The point to notice here is that they peered backward in experiential time to rediscover and reformat meaning, purpose, and their existing cultural map. These religious movements “synthesize many traditional cultural elements together with elements introduced from the dominant society.”18 When the collision of the new and the old impacts the status quo of traditional culture, some degree of syncretistic re-formation results. Yet, unless there is a holistic core that can cohere through the transition, splintering or fragmentation results reflecting varying degrees of syncretism of the old and the new.

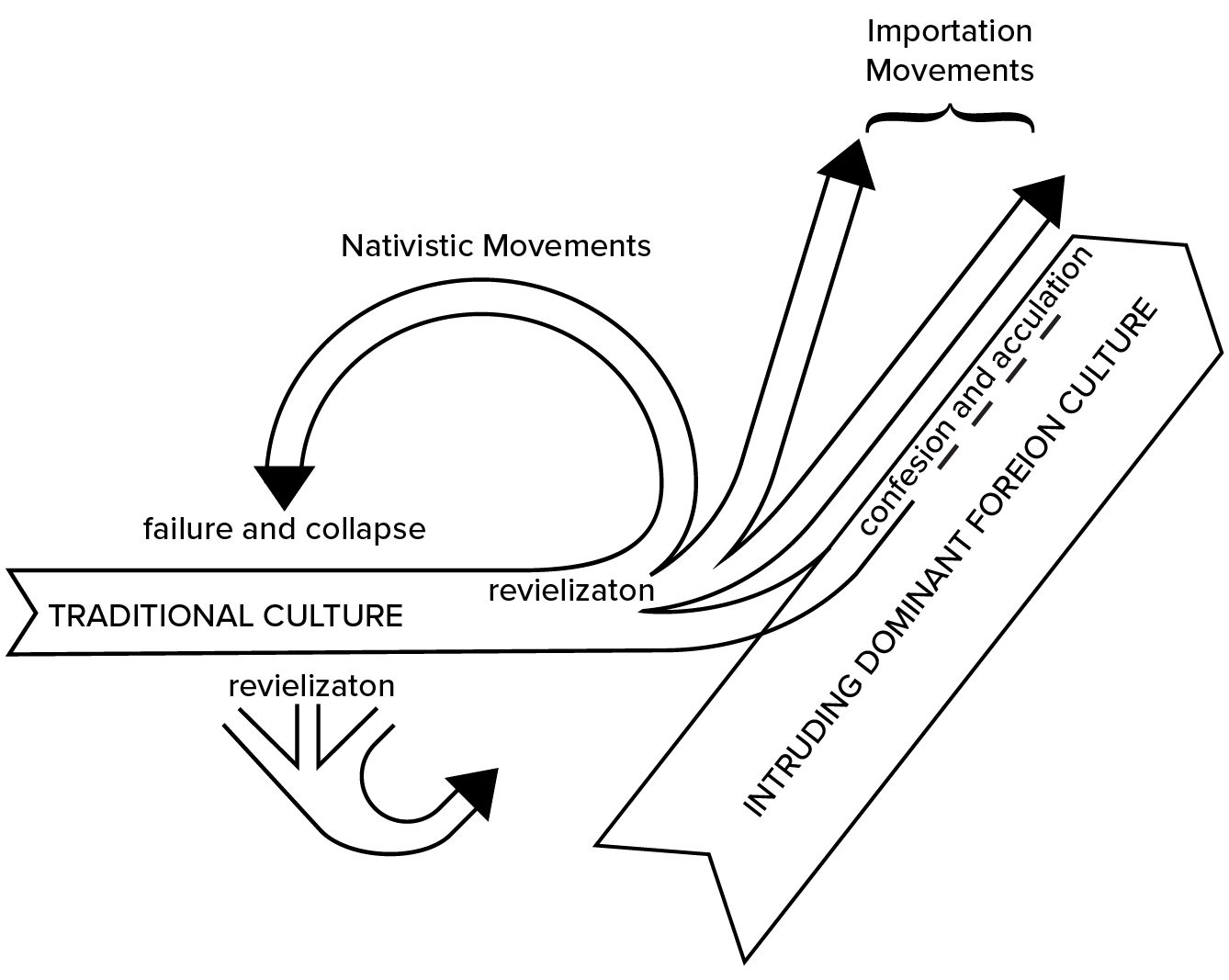

See the diagram below which Paul Hiebert uses to explain the essential elements of social change.19 Note, especially, the two items Hiebert terms “Importation Movements” in the diagram. In one sense, it seems believers in this postmodern era are vacillating between these two tributaries to practice forms of contextualization. One is nearer in proximity to conversion or capitulation to the external domineering and new cultural pattern. The other holds on to the anchored old beliefs and critiques and engages the new. As long as the Bible is that anchored influence, believers will live and speak with the prophetic voice of Scripture. If, however, dominance shifts toward the intruding new cultural dominance, then compromise happens.

Paradigm Shifts

Since socio-religious change is as old as humanity, anthropologists are able to track the patterns that usually unfold and thereby identify which options seem most feasible to forecast future trajectories. Integration will happen; the question is regarding what the outcomes will shape up to be like. Hiebert notes four likely scenarios:

- Engulfing or swallowing the new into the old system

- Substituting the new wholesale for the old

- Syncretistic blending of the old and new in ways not resembling either

- Compartmentalization of the old and new as separate realities in the same life experience whether contradictory or not20

Now, in the aftermath of the pivot point between two millennia, Christians are facing radical elements of change and challenge, especially in the West. Prophets are pointing believers back, back to anchor points in time. In one sense this cannot be avoided. It is the way social creatures react to preserve sense and meaning for reality. In North American evangelical circles, both traditionalists and postmodernists are looking back but to differing anchor points. Those influenced more heavily by postmodernism’s relativized definitions of truth tend to write off the period of church history from approximately AD 325 to the close of the twentieth century. Those intervening years are negatively termed Christendom.21 It is more than a period of time, it is a Zeitgeist or spirit of the time. Attitudes of early Christians are highly prized among advocates of the Emergent Church Movement who show postmodern influence and point to ways forward. For instance, Doug Pagitt says, “It may be quite necessary for some of us to move forward with the way of Jesus in ways that are not encumbered by the history of Christendom.”22 He also contends that “those outside the church have already concluded precisely this—the church, or self-professing Christians, hold no special right to speak for God. I contend that Christendom was useful when people of faith were having to engage in conversations with a dominant secular worldview.”23

Traditional spokespersons advocate looking backward as well, but to the more ancient roots of the raw data of the Christian faith, namely the Bible itself. Luther advocated this in his rendition of sola scriptura and reaffirmed God’s Word as the only source of reliable religious knowledge. As noted above, the controversy ensues over who has the ability to comprehend or access that original data and how. Hermeneutical and theological methods grow increasingly more significant when trying or testing the prophetic voices in this time of radical theological displacement. Competing voices show some degree of syncretistic reformulation of the faith. It is significant to the discussion to determine which adheres more consistently to what God’s Word actually says since generally both sets of prophets wish the “cargo” of genuine Christian belief to return. Varying degrees of biblical affirmation correlate to fragmented prescriptions of the future.

So it seems we are faced with a choice either to reaffirm biblically defined and determined hermeneutical commitments in order to detect the prophetic voice of God’s Word, or to embrace degrees of skepticism that assume the Bible’s meaning is generally irretrievable as propositional truth that may be identified, understood, and applied in contemporary pluralistic settings. These are the tensions of decision regarding a premise of priority for either sola scriptura or sola cultura. New postmodern theologies are emerging and point us to new communities of faith and new moral definitions for life in the “secular city.” They come with a loss of things sacred, transcendent, or theological.

J. Andrew Kirk, early in the now aging discussion of contextualization by evangelicals, drew a then obvious conclusion regarding theological truth. His more recent observations are particularly relevant when compared to the first item in 1983. During the intervening years, the epistemological paradigm shifted, at least most clearly so, in evangelical circles. In the older piece, Kirk noted that “culture is not right just because it is local. Exchanging the absolutist pretensions of Western cultures for the total autonomy of non-Western ones fails to take seriously both the universal and particular implications of Christ’s lordship.”24 Since there is a loss of foundational truths, and a conscious awareness of the centered self in relation to God, as well as a corresponding moral decay, Kirk now states that missiologically we must recover a “more convincing epistemological model” and that “this can only be done by retrieving an account of knowledge which brings together once again the Word of God and the Works of God into a consistent explanation of the whole of reality.”25

Syncretism, in Hiebert’s diagram of ideas noted above, is happening. Missiologically there is the tendency to do precisely what Kirk forewarned us about, namely localizing theological truth to the cultural level, now even to the personal or designer level. Syncretism does not need to evolve in such a way as to shift in that direction. A slippery slope can lead in more than one direction. To be obscurantist, capitulate God’s truth entirely, or to compartmentalize (Hiebert’s other alternatives) is not a pleasant set of options. The rub of syncretism will lead to transformation of the old or the new or both. In our rush to relevance, we are jeopardizing the prophetic voice of God that beckons human hearers to know Him and to respond in faith to His grace given in Christ for salvation and restoration of one’s centered self. A little leaven can leaven the whole lump, so flirtation with postmodernity’s epistemological categories works the rub of syncretistic tensions in the opposite direction and undermines the attempt to be relevant so that the outcome is secularly defined relevance without truth. Carson concludes that “it remains self-refuting to claim to know truly that we cannot know the truth.”26

How may we move ahead toward relevance without capitulation, preservation of the prophetic while at the same time demonstrating the most relevant reality of all, God’s Word, both living and written? Here is where the hermeneutical spiral reenters the drama and assists us in extracting timeless precepts from God’s Word. Paul applied a set of principles in pluralistic cultural settings. When taken together, these form a safeguard for believers against nefarious tensions that typically undermine biblical fidelity. His principles, which were also set forth in an era of cultural transition, are clearly relevant today even though they were formed during Jewish-Gentile culture wars among believers in the ancient church. He used them to encourage and instruct believers as they journeyed toward increasingly more complete transformation and pointed believers toward Christ’s image.

A Proposal for Practicing Biblically Dominant And Critical Contextualization

While living in West Africa, I first consciously encountered radical contrasts in cross-cultural values. These contrasts challenged my understanding of ethical standards. I looked for ways to communicate cross-culturally values that could be both biblical on the one hand and not necessarily Western on the other. While sometimes there may be coincidental definitions of ethical truth on absolute transcultural levels, there may also be differing ways to understand and apply said truths on the culturally specific levels. For example, “murder” is prohibited clearly and the prohibition against it applicable in any cultural setting wherever or whenever believers may live. Yet, socially acceptable guidelines and definitions about what constitutes “murder” are also subject to God’s prophetic critique. I have a former student, for example, that lives in a very remote tribal setting in the Pacific where female infanticide is practiced if a soothsayer looks into the child’s face at birth and detects an “evil” spirit. It seems to be a “witch” prevention program. Culturally, this is an acceptable condition for murder, and they routinely practice it. In the West, most nations practice a different form of infanticide based on a mother’s choice regarding abortion, commonly as a convenience for the mother. God’s Word stands in moral opposition to both. On the transcultural level, God forbids “murder,” but further analysis is required to know how to apply that absolute truth in relative and shifting contexts.

This is the nature of critical contextualization. This type of contextualization is genuinely critical, or value altering, and fosters transformation of life and worship of the one true God. Sherwood Lingenfelter, a missionary anthropologist, states it succinctly. He asserts, “Sin is seen as the pervasive corrupting force presented in Scripture, and culture is regarded not as a neutral objective entity that can be accommodated readily to the gospel, but rather a corrupted order that is inextricably linked to the unbelievers who participate in and perpetuate it Christ is the transformer of culture through his body on earth, the Church.”27 At the end of the day, where do we look to find how to ferret out God’s will for our relative realities wherever or whenever we may experience them? The apostle Paul used principles to address issues arising in the midst of similar cultural change dynamics in a radically transient societal mix during the founding days of the Church.

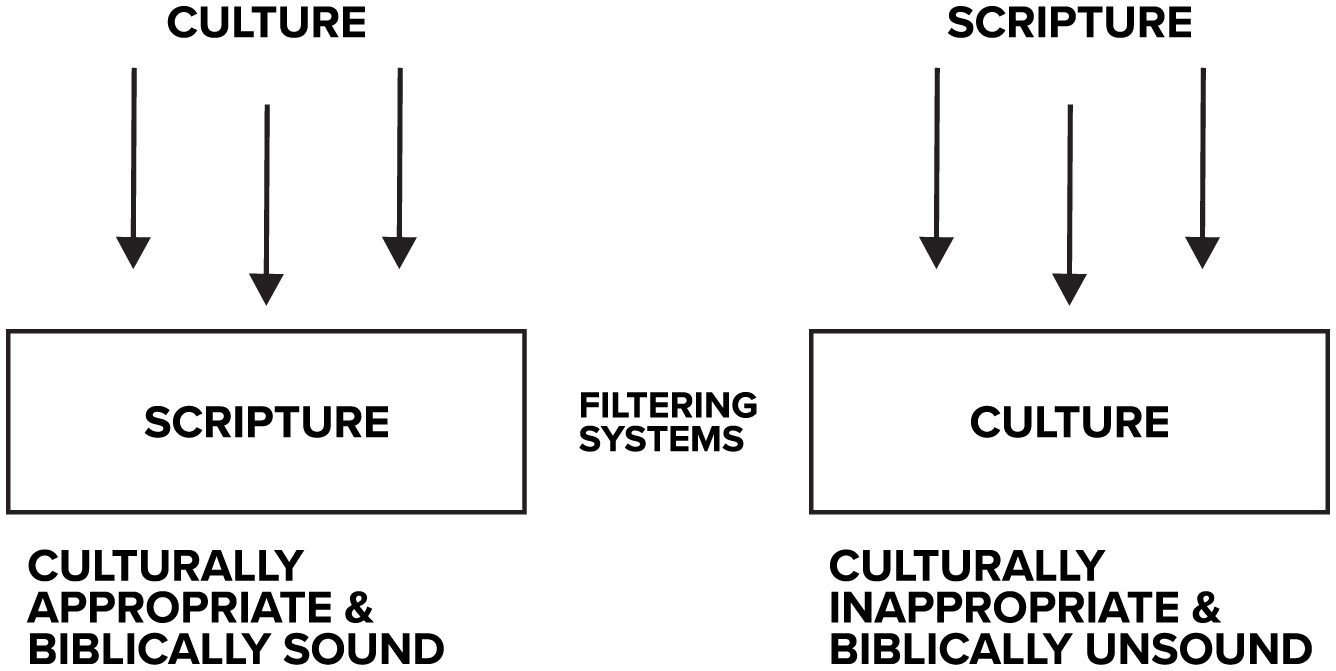

Especially when discerning God’s transcultural truth and developing biblical lifestyles within cultures, it is essential that we transplant biblical standards and not our own culture’s preferences. Not everything in a culture is automatically pleasing to God. As noted above by Lingenfelter, cultures are not neutral but all are tainted by sin. Thus, some things do conflict with God’s will in essence or in application. How can that be determined? We can make these judgments by filtering cultural assumptions, beliefs, practices, or customs through the grid of Scripture and not the reverse. Hence, our method is important, because sin is pervasive. If not carefully done, we can inadvertently do the analysis and allow our cultures to accrete over and dominate the process. When the latter happens, culture actively critiques Scripture rather than Scripture critiquing culture.

Scriptural dominance in contextualization safeguards against culture or experience being dominant. Metaphorically speaking, the “wire mesh” of the filters below are the set of five principles that Paul used in the first century Church’s culture clashes. They are also helpful to contemporary critical contextualizers in any cultural setting, because Paul asserted them as universal in meaning while flexible in application. The principles are more evident and practical when posed as questions to the culture in question and to the critical-contextualizer. The chart and accompanying descriptions below outline a practical proposal for our missional future.28

Five Pauline Principles For Filtering Culture Through the Grid of Scripture29

- Does it contradict any clear teaching of Scripture? 2 Tim 3:16-17

- Does it violate or do harm to my body (mentally, physically, or spiritually) as the temple of the Holy Spirit? 1 Cor 6:19- 20 Or, will it enhance the Holy Spirit’s development and expression of Christ’s holiness in and through my life? 1 Thess 4:1-8

- Does it cause my weaker brother (or non-believer by implication) to stumble in coming closer to Christ? 1 Cor 8-10

- Does it violate the express will of my spiritual head? Eph 5:22-6:9; Rom 13:1-730

- Does it glorify God? 1 Cor 10:31 Or, Can I ask God to bless it with a clear conscience? Rom 14:19-23

Conclusion

Is there a sola found in the mix between culture and Scripture? The most reasonable reply is simply, “both.” Yes, there should be a priority of voice for Scripture. God’s revelation to us clearly indicates that He intended it to be the absolute rule for truth, faith, and practice. Not only has He preserved it throughout its development, but He also provides the Holy Spirit to aid believers in rightly dividing the truth. So the priority of prophetic voice is essential in the contextualization conversation. Scripture, in this way, is the sola or only authority.

However, there is also a sense in which the culture has a solitary role. Human beings are the only ones instructed to be doers of the Word. Humans collectively construct cultures, worldviews, moral values, customs, and practices that have a push and pull effect on our experiences and lives. As the only prescribed doers, we should become willing listeners. In this role, we must conform to the text’s prescriptions for being good listeners and doers. Simply stated, Scripture’s literary forms, styles, and intended outcomes whether inspirational, didactic, prescriptive, or all of these, sets the conditions for the conversation and not the reverse. A hermeneutical spiral places us always in the reactive mode rather than being proactive. Hearing precedes yielding, and that is followed by action. Being proactive, however, devolves into eisegetical practices and ends up imposing experience into God’s truth. This is more than sequential priority; it is foundational for biblical epistemology.

Social change is messy, especially when religiously oriented. The church in the West seems to be in a “cargo cult” state of mind these days. We seem to be looking back to times that we think were better. The emergent village voices, influenced heavily by postmodern skepticism regarding God’s truth, wish to look back into the ancient church’s beliefs and practices to rediscover meaning. More historically evangelical voices prefer to ground religious knowledge even further back, in the scriptural texts themselves. Scripture should speak and critique experiences and cultures, but not the reverse.

Pauline principles point us to time tested tools for evaluating experience. Though this work is difficult and sometimes tedious, it yields eternally important results. Perhaps the words of William Carey, who himself held to a very high view of Scripture, can take on magnified meaning in the midst of this time of change. The order of his famous phrase that launched the modern missions movement among Protestants sets forth priorities and illustrates the roles for the dominant voice of scriptura and the listening heart of cultura. The church once again needs to expect great things from God and attempt great things for God! God specifically speaks in Scripture. Believers hear, act obediently, and do so with confidence in our missionary God’s revelational heart.

- David Jacobus Bosch, Transforming Mission: Paradigm Shifts in Theology of Mission (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1991), 366-67. ↩︎

- Edward Rommen, Get Real: On Evangelism in the Late Modern World (Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library, 2009), 182n371. ↩︎

- See, for example, the then contemporary writings by Stanley J. Grenz, The Millennial Maze: Sorting out Evangelical Options (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 1992); Stanley J. Grenz, Revisioning Evangelical Theology: A Fresh Agenda for the 21st Century (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 1993); Stanley J. Grenz and Roger E. Olson, 20th Century Theology: God & the World in a Transitional Age (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 1992); Lesslie Newbigin, Foolishness to the Greeks: The Gospel and Western Culture (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1986); Lesslie Newbigin, The Gospel in a Pluralist Society (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1989). ↩︎

- Bosch, Transforming Mission, 427. ↩︎

- Charles James Fensham, “Missiology for the Future: A Missiology in the Light of the Emerging Systemic Paradigm” (D.Theol. Thesis, The University of South Africa, 1990), 250- 51. Fensham was one of Bosch’s last doctoral students and reflects his influence as applied to ideological “futurist” thought and missiology ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Gustavo Gutiérrez, A Theology of Liberation: History, Politics, and Salvation (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1988). ↩︎

- H. Richard Niebuhr, Christ and Culture (New York: Harper & Row, 1975), 238. Paul’s definitive prescriptions regarding the gospel and his caveat against corrupting it, or being thrown about by fluid doctrinal winds, both fly in the face of Niebuhr’s assertions (see Gal 1:6-9 and Eph 4:14-24). ↩︎

- D. A. Carson, Christ and Culture Revisited (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2008), 90. See also the reasonable tests for truth rendered by Millard J. Erickson, Truth or Consequences: The Promise & Perils of Postmodernism (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2001), 268-71. ↩︎

- Carson, Christ and Culture Revisited, 90. ↩︎

- See D. A. Carson, Becoming Conversant with the Emerging Church: Understanding a Movement and Its Implications (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2005), 116-20. See also David J. Hesselgrave, “Contextualization and Revelational Epistemology,” in Hermeneutics, Inerrancy, and the Bible, ed. Earl D. Radmacher and Robert D. Preus (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1984), 693-738; and David J. Hesselgrave, “The Three Horizons: Culture, Integration, and Communication,” JETS 28, no. 4 (December 1985), 443-54. ↩︎

- Craig Van Gelder, The Essence of the Church: A Community Created by the Spirit (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2000), 41. Emphasis added. ↩︎

- Bosch, Transforming Mission, 427. For further illustration of this problem, see Keith E. Eitel, “Evangelical Agnosticism: Crafting a Different Gospel,” Southwestern Journal of Theology 49, no. 2 (Spring 2007): 150-66; and Keith E. Eitel, “Shifting to the First Person: On Being Missional,” Occasional Bulletin of the Evangelical Missiological Society 22, no. 1 (Winter 2009): 1-4. ↩︎

- Karen M. Ward,“The Emerging Church and Communal Theology,” in Listening to the Beliefs of Emerging Churches: Five Perspectives, ed. Robert Webber (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2007), 163-64. Emphasis added. The perspectives offered in this volume are presented by Mark Driscoll, John Burke, Dan Kimball, Doug Pagitt, and Karen Ward. ↩︎

- Alan Hirsch, The Forgotten Ways: Reactivating the Missional Church (Grand Rapid: Brazos Press, 2006), 156-57. Oddly, though, Hirsch embraces relativized methods evident in these trends in spite of the potential pitfalls he himself notes. ↩︎

- Abraham Rosman and Paula G. Rubel, The Tapestry of Culture: An Introduction to Cultural Anthropology (Glenview, Ill: Scott Foresman, 1981), 278. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- See Paul G. Hiebert, Cultural Anthropology (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1983), 388. ↩︎

- Hiebert, Cultural Anthropology, 422. Also, the chart above is from the same source. For another depiction of the ways new and old systems have mixed historically when the incoming ideas were generated by foreign missionaries in indigenous African cultures, see Lamin O. Sanneh, Translating the Message: The Missionary Impact on Culture (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1989). ↩︎

- See Bosch, Transforming Mission, 274-75. Bosch notes the synergy between development of state governments and the Church from Constantine’s time to the end of the Enlightenment and resultant mingling of motives for mission, especially since 1792. The era as a whole he terms “Christendom” or corpus Christianum as something of a sad saga between the ancient church and postmodern times. ↩︎

- Doug Pagitt, “The Emerging Church and Embodied Theology,” in Listening to the Beliefs of Emerging Churches, 132-33. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- J. Andrew Kirk, Theology and the Third World Church (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 1983), 37. ↩︎

- J. Andrew Kirk,“The Confusion of Epistemology in the West and Christian Mission,” Tyndale Bulletin 55, no. 1 (2004): 152. ↩︎

- Carson, Christ and Culture, 90-91 ↩︎

- Sherwood G. Lingenfelter, Transforming Culture: A Challenge for Christian Mission (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1992), 204-05. For further explication of the concept of critical realism and the consequent idea of critical contextualization, see Sherwood G. Lingenfelter, Agents of Transformation: A Guide for Effective Cross-Cultural Ministry (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1996); and Paul G. Hiebert, The Gospel in Human Contexts: Anthropological Explorations for Contemporary Missions (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2009). For elaboration of the hermeneutical processes needed to insure that God’s Word critiques culture rather than the reverse, and to further insure that it is God’s Word that transfers to the host cultural setting (foreign or not), consult William J. Larkin, Culture and Biblical Hermeneutics: Interpreting and Applying the Authoritative Word in a Relativistic Age (Grand Rapids: Book, 1988). Finally, see especially the five step practical process suggested by Grant R. Osborne, “Preaching the Gospels: Methodology and Contextualization,” JETS 27, no. 1 (March 1984): 27-42. These sources undergird the presuppositions found in what follows regarding Pauline practices in the ancient church. ↩︎

- For a more complete development of these concepts, see Keith E. Eitel,“Transcultural Gospel—Crossing Cultural Barriers,” Evangelical Missions Quarterly 23, no. 2 (April 1987): 130-38; and Keith E. Eitel, Developing a Biblical Ethic in an African Context (Nairobi: Evangel Publishing, 1987). ↩︎

- In the following principles, “it” refers to a worldview assumption, cultural belief, or custom subject to biblical evaluation. ↩︎

- If the spiritual head prescribes something requiring personal sin against God, then believers should not obey their spiritual heads in those circumstances. ↩︎