The Use of the Old Testament in the New Testament

Southwestern Journal of Theology

Volume 64, No. 1 – Fall 2021

Editor: David S. Dockery

Here I do not seek to address Paul’s hermeneutic as a whole, but to focus on its continuity with earlier Scripture, especially in his treatment of the law. There is such a vast range of views and arguments regarding this subject that I can offer only some sample thoughts here.1 I also explore some aspects of the law itself (albeit recognizing my limitations as a NT scholar) to illustrate why Paul was right to approach the law as he did.2 Given limited space, I have focused on the biblical text itself rather than the voluminous secondary literature.

My emphasis, then, is Paul’s consistency with the spirit of the law. Still, it bears further mention that Paul, like Jesus, models a way of reading Scripture that goes beyond merely mechanical exegetical methods.3 Paul applies biblical texts in various ways for various purposes (e.g., responding to critics’ polemic, in contrast to normal exposition). In normal circumstances, however, the original sense of the text remains foundational as in exegesis today. Yet beyond mechanical exegetical method, he trusts that God still speaks in Scripture, and welcomes its principles to speak in analogous ways to new settings. In that way, the message remains alive and fresh for each generation and new cultural setting because the heart of its message addresses pressing issues that God’s people continue to face.

I. TWO WAYS OF READING

Paul contrasts two ways of reading the law: the law of works and the law of faith (Rom 3:27).4 That is, we may wrongly approach the law as a means of self-justification,5 or we may approach it as a witness to the way of reliance on (faith in) God’s covenant grace. Thus God’s own people, pursuing the law’s righteousness as if it were achieved by works, failed to achieve it because they did not pursue it by faith; by trusting in the God of the covenant who would graciously transform them (Rom 9:31–32).6 As a merely external standard, the law could pronounce death; but its principles could instead be written in the heart by the Spirit (8:2), an eschatological promise for God’s people (Ezek 36:27).

In Rom 3:31, Paul shows that trust in God’s action in Christ to make us right with God does not annul the law. Indeed, it supports the law’s real message (Rom 3:31). In this verse, Paul concludes a line of argument, but also foreshadows what is to come.7 He goes on to argue his case directly from the law, which in his circles included the entire Pentateuch. Paul’s interest is in God’s character revealed in narratives that put the law’s regulations in context. In Romams 4, then, Paul argues from Abraham’s example in Gen 15:6: God accepted Abraham’s trust in him as righteousness. Paul uses the context in Genesis to point out that God accounted Abraham as righteous even years before he was circumcised (Rom 4:10) so that this experience is possible without the outward sign of circumcision (4:11).

In Rom 9:30–10:10, Paul presents two approaches to the law and righteousness, but he believes that only one (the way of faith) can genuinely save sinful people of flesh.8 Based on the foregoing scriptural argument (that God does not save based on membership in ethnic Israel), Paul in 9:30–33 addresses the reason for Israel’s failure to be saved. Seeking righteousness through the law, Israel could not fulfill the law (9:31) because they approached the law the wrong way: As a standard rather than an invitation to depend on God’s kindness (9:32). In 9:32–33, Paul notes that Scripture had already indicated Israel’s failure (he also notes this in 10:16): Many in Zion would stumble, except those who trusted in the rock of their salvation (Isa 8:14 blended with Isa 28:16).

Paul has already indicated that the right way to use the law is to inspire trust in God’s gracious, saving acts rather than confidence in one’s own keeping of its precepts (3:27, 31; cf. 8:2). Israel’s wrongheaded approach to the law was by works rather than by faith (9:31–32); in 10:5 Paul offers a basic text for this wrong approach of works and in 10:6–8 counters with a text for the right approach of faith.9 Later Jewish teachers did apply texts like those in 10:5 (especially Lev 18:5; also Gal 3:12) to eternal life,10 even though these passages originally meant just long life in the land.11 It is probable that Paul has heard this proof-text in his debates in the synagogues. Paul does not need to elaborate on why the approach to the law in 10:5 is unworkable; he has already addressed the failure of law-works due to human sinfulness in 3:10–18 and elsewhere, and most recently in 9:31–32 (cf. 3:21; 4:13; Gal 2:21; 3:21; Phil 3:6, 9).

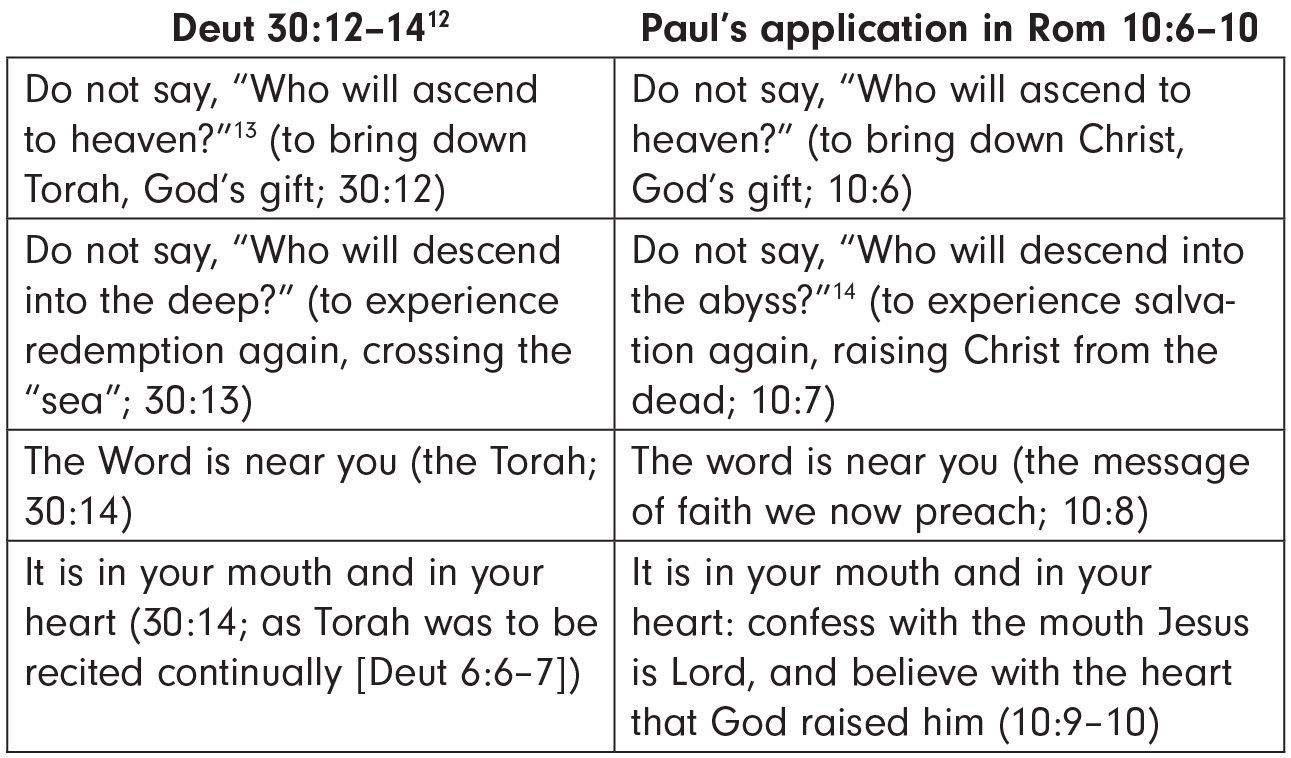

Paul develops his case further by drawing an analogy between Moses’s era and his own: Salvation and God’s word came in both eras. Just as God himself redeemed Israel, bringing his people through the sea and giving them the Torah (Deut 30:12–13), so now God himself brought Jesus down and raised him from the dead (Rom 10:6–7). Just as God enjoined Israel to follow the law by keeping it in their heart and mouth (Deut 30:14), so now his message, the good news inviting faith, resides in the heart and is expressed by the mouth (Rom 10:8–10). (Paul adapts his chief passage’s wording (“Lest you say”) to “Do not say in your heart,” which manages to incorporate a slight allusion to Deut 9:4. The context of that passage reminds Israel that God is not giving them the land because of their righteousness.)

Paul argues by analogy from God’s salvation and word in Moses’s era to God’s way of saving and God’s word in Paul’s own era of the new covenant.15 The law was not too difficult for Israel (Deut 30:11), provided it was written in the heart (Deut 5:29; 10:16; 30:6). Paul agrees (Rom 8:2–4), while expecting this heart-writing to be fulfilled widely only in the new covenant (Jer 31:33; cf. Ps 37:31; 40:8; 119:80, 112; Isa 51:7). Just as Israel did not bring the gift of God’s righteous law near by their own ability (Deut 30:12–13), so God’s righteousness is a gift. Just as God prefaced the Ten Commandments with a reminder of redemption (Exod 20:2), so now salvation from sin remained by grace through trust in God’s word, expressed by embracing his word. The heart trusts what God has done for salvation, and the mouth acknowledges Christ as Lord.

II. THE SPIRIT OF THE LAW: CONTINUING PRINCIPLES, ADJUSTED CONTENT

Even apart from his Christocentric gospel, Paul’s approach to the law reads it in a wider perspective than that of many of his Jewish contemporaries. The principles of the law endure, but because God gave the law in a specific cultural setting and for specific circumstances in salvation history, the specifics of obedience look different in different times.

1. Both different and the same. The God of the OT remains the same God in the NT and today, despite addressing different sorts of circumstances. Salvation has always been by grace through faith, expressed by following his message (Gen 15:6; cf. 6:8). God chose Israel not because of their righteousness (Deut 9:4–6) or their greatness, but because of his love (Deut 7:7–9; cf. Eph 2:8–10). The God of Deuteronomy longs for our obedience for our good (Deut 5:29; 30:19–20); likewise, Paul expects us to express genuine faith by obedience (Rom 1:5; 16:25). God writes his law in the hearts of his people by the Spirit (Rom 8:2; cf. 2 Cor 3:3); as participants in a new creation, we should live new life by God’s gift of righteousness (Rom 6:4, 11).16

This does not mean that nothing has changed. In Scripture, covenant faithfulness is always expressed through obedience; it grows from a relationship with God initiated by God himself. Yet the specific content of obedience may change from one era to another, not only in response to changes in culture, but in response to developments in God’s revelation or his plan in history. In Moses’s day, no one could protest, “Since Abraham did not keep the law against planting trees in worship, neither will I” (cf. Gen 21:33; Deut 16:21), or, “Since Jacob could marry sisters, so can I” (cf. Gen 29:30; Lev 18:18), or, “Since Jacob could set up a pillar for worship, so can I” (cf. Gen 28:22; 31:13; 35:14; Lev 26:1; Deut 16:22).

Likewise, the coming of Jesus the promised deliverer changed the relevance of specific content, shifting the emphasis from some outward signs of the covenant to fuller inner transformation (cf. Rom 2:29; Col 2:16–17; Heb 8:5; 10:1) by the promised eschatological Spirit (Ezek 36:27). For that matter (as some other Jewish interpreters also recognized), some stipulations of the Torah could not be observed literally once the temple was destroyed, or outside the Holy Land, or in non-agrarian settings. No one by Paul’s day, or for that matter by Ezekiel’s day, could honestly expect otherwise.

2. Spirit of the law in ancient Israel. Long before Jesus came, Scripture already illustrated the difference between following God legalistically and following him from the heart. Jewish sages widely recognized this principle, even if they usually did not take it as far as Jesus did.17

One finds examples, for instance, in the life of Saul. After God gives Israel a great victory through Jonathan’s courage and faith (1 Sam 14:6– 12), Saul wants to kill him to honor a fast that Saul has declared (14:24, 43–45)—a fast that proves to be a bad idea anyway (14:29–34). Whereas Saul refuses to enforce the full herem on the Amalekites and their animals, which God had commanded (1 Sam 15:3, 14–29), he slaughters all the priests and their animals, the antithesis of God’s will (22:18–19). This is because the high priest gave bread (21:4–6) to David, a man after God’s heart (13:14) whom Saul feared. The priest giving David sacred bread, incidentally, is used by Jesus to illustrate his principle of meeting hunger over always observing ritual demands (Mark 2:26; Matt 12:3–4; cf. John 2:3–10); Jesus and his hearers naturally favor the high priest over Saul. Saul’s zeal for Israel leads him to kill Gibeonites (2 Sam 21:2) despite the ancestral covenant (Josh 9:19–20), and thereby brings judgment against Israel and ultimately Saul’s own household (2 Sam 21:1, 6).

When Hezekiah and his princes realize that not enough priests will be ready to sacrifice the Passover for all the people, they reschedule the Passover (2 Chr 30:2–5). The participation of more of the people is more valuable in God’s sight than the specific date; moreover, in response to Hezekiah’s prayer, God overlooks that many of the people, though seeking God, have not consecrated themselves ritually beforehand (30:17–20). The narrative is clear that God favors Hezekiah and this Passover celebration (30:12, 20, 27). The people come closer to fulfilling the spirit of the law here than they have done for generations, and God is pleased despite several breaches of ritual practice.18

Compare also the priest and the Levite in Jesus’s story of the Good Samaritan. Priests and Levites could render themselves ritually impure by touching a dead body, and the victim beside the road appears to be quite possibly dead (Luke 10:30).19 These ministers are not heading to Jerusalem to serve, but back to Jericho, where many wealthy priests lived; nevertheless, they do not risk helping someone who might be dead anyway. Instead, a despised Samaritan rescues the Jewish stranger (10:33–35).20 The context of the passage that Jesus is explaining (Lev 19:18; Luke 10:27) includes loving foreigners in the land (Lev 19:34).

In today’s language, the spirit of the law often took precedence over its details (or in some of these cases, over other attempted expressions of zeal). In Romans 7, Paul depicts a wrong approach to the law, based on the mind knowing what is right without having a new, pure identity in Christ. In contrast to the expectations of some ancient thinkers, merely knowing what was right did not produce right volition as long as the mind found itself subject to the passions rather than empowered by God’s Spirit.21

By contrast, we can live according to the spirit of the law by the Holy Spirit in our hearts (Rom 8:2).22 The prophet Ezekiel had already promised that God would wash the hearts of his people and give them new hearts and spirits. By his Spirit in them they would fulfill his laws (Ezek 36:25–27). Paul was not the only early Christian writer to recognize this. When John refers to being born of water and one’s spirit being born of the Spirit, he plainly evokes Ezekiel’s promise (John 3:5–6); he goes on to compare God’s Spirit with wind in 3:8, an image from Ezekiel’s following chapter (Ezek 37:9–14). Fulfilling God’s covenant stipulations by the Spirit looks different from the old way of keeping commandments.

3. The heart of the law. The Torah itself included statements that summarized the heart of what God wanted most (Deut 10:12–13), and so did the prophets (Mic 6:8). Later tradition claimed that the early Jewish sage Hillel summarized the heart of the law in a manner similar to Jesus’s teaching that we call the golden rule (Luke 6:31; esp. Matt 7:12).23 First-century sages also debated which commandment was the greatest; although no consensus was achieved (the most common was apparently honor of parents), one rabbi later than Jesus came close to his view, citing love of neighbor.24 Jesus’s joint emphasis on love of God and love of neighbor (Mark 12:28–34),25 however, became a distinctive hallmark for his movement. Others valued love, but multiple circles of Jesus’s followers consistently highlighted this as the supreme commandment (Rom 13:9–10; Gal 5:14; Jas 2:8; cf. 1 Cor 13:13).

III. APPLYING PAUL’S PRINCIPLES

Although Paul affirms that believers are not under the law in the sense of needing it for justification, he does expect believers to fulfill the moral principles of the law. Unfortunately, Christians disagree widely among ourselves on how to distinguish transcultural principles from their concrete applications, on the degree of continuity between the law enshrined in the Pentateuch, and on what rules we should follow as Christians.

Despite disputes regarding details, certainly we can look for areas of continuity, for example, eternal principles (albeit expressed in concrete cultural forms), as Jesus did. We can look for God’s heart in the Torah (e.g., in Exod 33:19–34:7). Similarly, the Spirit was often dramatically active in ancient Israel (e.g., 1 Sam 10:5–6, 10; 19:20–24), including in prophetically inspired worship (1 Chr 25:1–3); surely in the new covenant era (Acts 2:17–18) we should expect not less but more experience of the eschatologically outpoured Spirit.

Romans 14 suggests that Paul does not require Gentile Christians to practice the kashrut, or food purity customs, that were meant to separate Israel from the nations (Deut 14:2–3).26 His remarks about special holy days (Rom 14:5–6; cf. Gal 4:10; Col 2:16) appear more complicated. If Paul includes the Sabbath here, how do we reconcile his theology here with other parts of Scripture?27 God himself models the Sabbath principle for Israel in creation (Gen 2:2–3); it does not begin with Moses. Sabbath violation incurs a death penalty under the law (Exod 31:14–15; 35:2; Num 15:32–36), so it appears to be among the offenses that God takes quite seriously. God promises to welcome Gentiles into his covenant, provided they observe his Sabbaths (Isa 56:6–7). Jesus used his authority to clarify the ideal character of the Sabbath in some respects (e.g., Mark 2:25–28), but he did not explicitly abolish it.28

If Paul supports the spirit of the law, would he change one of the Ten Commandments with no explanation? Perhaps Paul recognized that most slaves and Gentiles could not get off work. Perhaps Paul is being flexible about how the Sabbath should be observed (for example, on which day, although Acts continues to apply the term consistently to the day of its regular observance—Acts 13:14, 27, 42, 44; 15:21; 16:13; 17:2; 18:4). Perhaps, and I think this somewhat more likely, Paul was saying that it was all right to revere special days such as the Sabbath (as among most Jewish believers) but all right also if one revered every day. In the case of the Sabbath, this would mean that we would devote not only one special day a week to God, but seek to devote all our time to him. One caveat should be noted here: using the continual Sabbath idea as an excuse not to rest at all, as I suspect some busy Christians do, defeats the still-valid point for which God originally instituted the Sabbath.

In any case, the biblical Sabbath principle applied to livestock and agricultural land as well as to people (Exod 20:10; 23:11–12; Lev 25:4; Deut 5:14), probably on the principle that living things need time to rest and rejuvenate. We are created beings who must acknowledge our good limitations. It is therefore at least wise, whatever one’s theology on the particulars, that humans observe a day of rest.

Most matters are less difficult to resolve than the Sabbath question. To further understand Paul’s approach to the law, it is valuable to digress to examine the law itself. Its principles invite interpreters to sensitively apply it in new ways when it moves beyond the settings for which its concrete forms were first designed.

IV. INTERPRETING BIBICAL LAW

Jesus’s and Paul’s hermeneutics value the law’s principles over culture-specific applications—although it must be admitted that in practice there is a wide range of difference among interpreters today over which are the universal principles and which are the culture-specific applications!29

1. Comparing Israel’s laws with those of her neighbors. If we compare Israel’s law with those of Israel’s neighbors, we quickly find shared legal categories as well as some differences in ethics. The shared categories show us what kinds of issues ancient Near Eastern legal collections normally addressed.30

Despite a shared legal milieu and thus many parallels, there are some noteworthy contrasts. The Ten Commandments lack any exact parallel; usually the closest cited parallels are a much longer Egyptian list of Negative Confessions, which also include such praiseworthy denials as, “I have never eaten human dung.”31 Another major contrast was the matter of social rank. All other ancient Near Eastern and Mediterranean legal collections included class-based penalties with respect to victims and perpetrators.32 Israel has the only known ancient Near Eastern legal collection that refuses to take class into account (with the exception of the division between slave and free, noted below).

Some laws might openly oppose contemporary customs or ideas; thus Exod 22:19, Lev 20:15–16, and Deut 27:21 condemn human intercourse with animals, even though pagan myths depict deities sometimes turning into animals before intercourse.33 Sacrificing to other gods is a capital offense in Exod 22:20, but nearly all surrounding cultures promoted it. Surrounding cultures exploited various forms of divination,34 but in Israel it was a capital offense and is expressly contrasted with the behavior of surrounding nations (Deut 18:9–14).

Some contrasts appear among significant formal commonalities. Canaanites, like Israelites, had thank offerings, atonement offerings, sin offerings, and so forth, but Canaanites also had sacrifices to produce rain and fertility, whereas Israel’s fertility came through observing God’s covenant.35 Israel had ritual purity laws about what was clean and unclean, but Hittites used such rules as magical prophylaxis against demons.36 Most cultures had food prohibitions; Israel’s are distinctive to keep them separate from the nations (cf. Lev 11:44–45; Deut 14:2–3), a separation no longer needed for believers under the new covenant, since they are consecrated and empowered for mission.

2. Concessions to human sinfulness. Jesus regarded some regulations as concessions to human sinfulness: “Moses gave you this commandment because your hearts were hard” (Mark 10:5).37 Jesus taught that God’s ideal was actually higher than the requirements of the law, which often made accommodations for human sinfulness. Thus the law regulated and limited sin rather than changed hearts and all mores.

Thus some laws are less than God’s ideal. Take, for example, indentured servants. If a slaveholder beats the slave there is punishment, analogous to that of a free person (Exod 21:18–21).38 But the slave is still called the slaveholder’s “money” (Exod 21:21); that is, the slaveholder paid money for the slave. Likewise, sexual abuse of slave women was punished but not as severely as if the slave were free (cf. Lev 19:20 with Deut 22:25–26).39 The law did not institute or ratify slavery; instead, it regulated and thus reduced abuses in a contemporary custom. But despite the abolition of class differences among free persons, the law did not abolish the distinction between slave and free, in contrast to NT teaching (1 Cor 12:13; Gal 3:28; Eph 6:8; Col 3:11). Likewise, the law regulates polygyny (prohibiting sororal polygyny and royal polygyny; Lev 18:18; Deut 17:17) rather than abolishing it. Many also place holy war in this category.40

In no society do civil laws represent the ideal of virtue; they are simply a minimum standard to enable society to work together. Israel’s laws at least limited sin, and they often, though not on every matter, did so more than surrounding cultures (e.g., by Israelites being expected to offer refuge to escaped slaves41 and to avoid judging by class divisions). To some extent, later rabbis recognized this: They legislated by extrapolating civil laws for particular cases, but at least in their legal traditions (later recorded especially in the Mishnah and Talmuds), they did so primarily as lawyers rather than as ethicists. Yet both Israel’s history and ways that many Muslims in areas of sharia law circumvent it show that external laws by themselves are insufficient to transform hearts, even if in certain periods they may improve the social conditions that affect hearts. For Paul, only Christ in the heart delivers us from sin, and even most genuinely committed Christians do not walk in the light of that reality continually.

We thus need to be careful how we extrapolate ethics from law. Jesus was clear that God’s morality is higher than the law. Whereas Israel’s civil law said, “You shall not kill” or “commit adultery,” Jesus said, “You shall not want to kill” or “want to commit adultery” (Matt 5:21–29). Attention to the laws’ genre allows us to read them in the larger context of God’s character and intention as the NT does.

3. Understanding and applying God’s law. God originally gave these laws to an ancient Near Eastern people addressing a different legal milieu than ours today, although subsequent legal systems have retained many legal categories and approaches, such as lex talionis, issues of negligence and liability, demands for evidence, and consideration of intention.

Culture determined the legal issues to be addressed, but not necessarily the content. Capital sentences reveal some issues that the law took quite seriously. It prescribed death sentences for murder, sorcery, idolatry and blasphemy, Sabbath violation, persistent drunken rebellion against parents, kidnapping (slave trading), and sex outside of marriage (adultery, premarital sex with a man other than one’s future husband, same-sex intercourse, and intercourse with animals). No one would suggest that Israel’s laws invite us to execute capital punishment for these offenses in the church today; this was a civil law with penalties intended as deterrents in society (Deut 13:10–11; 17:12–13; 19:18–20; 21:21). Nevertheless, they do suggest that Israel’s God deemed all of these offenses serious; otherwise, he presumably would have deemed execution too excessive.

But does this mean that God did not take other offenses seriously? Would it not be far better to abolish slavery than to merely regulate it?42 Remember that Jesus demands an ethic higher than the law, such as avoiding desiring another’s spouse, breaking one’s marriage, and the like.

Some principles in the law are stated overtly in ways that easily translate beyond local culture—the Ten Commandments, for example (apodictic rather than casuistic law). The law also includes other explicit principles based on God’s values, such as the following:

- be kind to foreigners in the land for you were foreigners in Egypt (Lev 19:34; Deut 10:19),

- love your neighbor as yourself (Lev 19:18),

- ethical principles behind the mere limitations of sin, and

- God seeking to inculcate character in his people by how they habitually treat other creatures: Don’t muzzle the threshing ox (Deut 25:4), don’t take a mother bird with her young (Deut 22:6), and give Sabbath rest to your animals (Exod 23:12; Deut 5:14).

In other cases, however, recontextualizing the message requires more careful consideration. For example, tithing was already an ancient Near Eastern custom43 and is only one facet of a much larger network of teaching about stewardship in the Torah. The tithes went to support the landless priests and Levites and for a festival every third year (e.g., Deut 14:22–23; 26:12). Jesus articulates demands for stewardship more exacting than the Torah: We and therefore everything we have belongs to God (Luke 12:33; 14:33). Scrupulous tithing cannot supplant greater biblical demands such as justice and love (Matt 23:23; Luke 11:32; cf. Luke 18:12).

V. THE OLD TESTAMENT GOD OF LOVE

The supposed contrast between the NT God of love and the OT God of wrath owes more to Marcion than to the principles of the Torah. The civil and ritual laws in the Torah expressed divine righteousness in a limited but culturally relevant way. Ultimately, however, the Torah already revealed God’s heart in many respects. The theology of Deuteronomy emphasizes God loving and choosing his people (Deut 7:6–9; 4:37; 9:5–6; 10:15; 14:2). Love for God likewise demands obedience (6:4–6; 11:1; 19:9; 30:16) and fidelity to God (avoiding false gods, 6:4–5; 13:6–10). God summons his people to circumcise their hearts (10:16; cf. Lev 26:41; Jer 4:4; 9:26) and promises to circumcise their hearts so they may love him fully (Deut 30:6).

The God of the OT period did not undergo evangelical conversion just prior to the NT. He had often called his people to himself for their own good (Jer 2:13; Hos 13:9). He lamented with the pain of spurned love or a forsaken parent when his people turned after other gods (Deut 32:18; Jer 3:1–2; Hos 1:2; 11:1–4), but yearned to restore them to himself (Jer 31:20; Hos 2:14–23). His heart broke when he had to punish his people (e.g., Judg 10:16; Hos 11:8–9).

Israel’s loving God, her betrayed and wounded lover, is ultimately fully revealed in Jesus as the God of the cross, the God who would rather bear our judgment than let us be estranged from him forever. Paul and other NT writers thus embraced the spirit of the law far more effectively than did their detractors.

- For a recent range of views, see helpfully Benjamin L. Merkle, Discontinuity to Continuity: A Survey of Dispensational and Covenant Theologians (Bellingham, WA: Lexham, 2020). ↩︎

- In condensed form, I draw here esp. on Craig S. Keener, Spirit Hermeneutics: Reading Scripture in Light of Pentecost (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2016), 219–36. ↩︎

- See Keener, Spirit Hermeneutics, 207–18. ↩︎

- Scholars divide on whether to translate nomos here as “law” or “principle”; the English choice may be forced, but if one must choose, the context has consistently employed the term for the Torah (Rom 2:12–27; 3:19–21, 28, 31). Cf. Marius Victorinus Gal. 1.2.9 in Mark J. Edwards, Galatians, Ephesians, Philippians, ACCS NT 8 (Downers Grove: IVP, 1999), 31. ↩︎

- Whether individually or as part of a corporate people. I cannot here take space to address the New Perspective(s) and its detractors; Gentile converts, at least, probably found the law’s stipulations more onerous than someone who grew up with them. For discussion of various perspectives, see Craig S. Keener, Galatians: A Commentary (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2019), 242–44; on early Jewish soteriology, 238–42. ↩︎

- Most Jewish interpreters would have insisted that they belonged to the covenant because they belonged to God’s covenant people, a belonging that they confirmed by keeping the covenant. Paul is more rigorous in demanding righteousness and expects it from hearts transformed by the Spirit and obedient to God’s Messiah, but he undoubtedly uses some hyperbole; see discussion in Craig S. Keener, Romans (Eugene, OR: Cascade, 2009), 4–9, 122–23. ↩︎

- Ancient writers could use transitions (e.g., Rhetorica and Herennium 4.26.35). On Rom 3:31, cf. C. Thomas Rhyne, Faith Establishes the Law, SBLDS 55 (Chico, CA: Scholars Press, 1981), 75. ↩︎

- I borrow this paragraph from Keener, Romans, 122. ↩︎

- Jewish teachers often defended positions by citing counter-texts to refute what they viewed as a misunderstanding of other texts. Sometimes they even temporarily came down to the level of their erroneous interlocutors (David Daube, “Three Notes Having to Do with Johanan ben Zaccai,” JTS 11, no. 1 [April 1960]: 54). Comparing one’s argument with that of an opponent was common (R. Dean Anderson Jr., Glossary of Greek Rhetorical Terms Connected to Methods of Argumentation, Figures, and Tropes from Anaximenes to Quintilian [Leuven: Peeters, 2000], 22). ↩︎

- See e.g., Simon J. Gathercole, Where Is Boasting? Early Jewish Soteriology and Paul’s Response in Romans 1–5 (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002), 100–2 (on CD 3.14–16, 20); Sigurd Grindheim, “Apostate Turned Prophet: Paul’s Prophetic Self-Understanding and Prophetic Hermeneutic with Special Reference to Galatians 3.10–12,” NTS 53, no. 4 (2007): 561–62; Timothy G. Gombis, “Arguing with Scripture in Galatia: Galatians 3:10–14 as a Series of Ad Hoc Arguments,” in Galatians and Christian Theology: Justification, the Gospel, and Ethics in Paul’s Letter, ed. Mark W. Elliott et al. (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2014), 82–90. Other texts make the connection between obedience and life (e.g., Neh 9:29; Ezek 20:11–13, 21; 33:12–19), probably echoing Lev 18:5; it might reflect court idiom (Gen 42:18). ↩︎

- Cf. Deut 4:1, 26, 40; 5:33; 8:1; 16:20; 30:16, 20. Still, they offer principles that can be extrapolated. ↩︎

- I borrow this chart from Keener, Romans, 126. ↩︎

- In later Jewish traditions, Moses ascended all the way to heaven to receive the Torah (Sipre Deut. 49.2.1). ↩︎

- The lxx uses this term at times for the depths of the sea (e.g., Job 28:14; 38:16, 30; Ps 33:7; Sir 24:29; Pr Man 3), sometimes, as here, in contrast to heaven (Ps 107:26). ↩︎

- The parallel between Christ and law here makes sense in view of early Christian association of Jesus with wisdom (e.g., 1 Cor 8:6; Col 1:15–17; later, John 1:1–18); wisdom was often associated with Torah (Sir 24:23; 34:8; 39:1; Bar 3:29–4:1; 4 Macc 1:16–17; Sipre Deut. 37.1.3). As Paul surely knew, Bar 3:29–30 in fact applies this very Deuteronomy passage to wisdom/law. ↩︎

- See at greater length Craig S. Keener, The Mind of the Spirit: Paul’s Approach to Transformed Thinking (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2016). ↩︎

- Cf. later rabbis’ comments on the different kinds of Pharisees in m. Sot. 3:4; Ab. R. Nat. 37A; 45, §124B; b. Sot. 22b; y. Sot. 5:5, §2; George Foot Moore, Judaism in the First Centuries of the Christian Era, 3 vols. (New York: Schocken, 1971), 2:193. ↩︎

- This is not to say that God ordinarily welcomed such breaches; disrespect to God’s presence in the ark brought death (2 Sam 6:6–8; 1 Chr 13:9–11; 15:2, 15), and God was angry with those who appointed priests who were not Levites (1 Kgs 12:32; 13:33; 2 Chr 11:14). ↩︎

- For people who are “half-dead” appearing as if dead in ancient sources, see Euripides, Alcestis 141–43; Apollodorus, Bibl. 3.6.8; Callimachus, Hymn 6 (to Demeter), line 59; Nepos, Pausanias 5.4; Livy 23.15.8; 40.4.15; Catullus 50.15; Quintus Curtius Rufus 4.8.8; Suetonius, Divus Augustus 6; for further details on the parable, see Craig S. Keener, “Some New Testament Invitations to Ethnic Reconciliation,” EvQ 75, no. 3 (2003): 202–7. ↩︎

- Some suggest that the Samaritan’s action is all the more shocking because of other Jewish parables in which the third and righteous actor is an Israelite (Joachim Jeremias, The Parables of Jesus, 2nd rev. ed. [New York: Scribner’s, 1972], 203). ↩︎

- See here Keener, Mind, chs. 2–4, esp. ch. 3. ↩︎

- Patristic interpreters often welcomed the ethos of the law while rejecting its ceremonial aspects (see e.g., Ambrosiaster in Karla Pollmann and Mark W. Elliott, “Galatians in the Early Church: Five Case Studies,” in Galatians, ed. Elliott et al., 46–47). Some distinguished between commandments of universal moral import and those limited to Israel (e.g., Theodoret, Epistle to the Galatians 2.15–16 in Edwards, Galatians, 29). This recognition does not require us to suppose that Paul’s “works of the law” be limited only to ceremonial law, the position of Origen, Jerome, and Erasmus opposed by Augustine, Luther, and Calvin (see John M. Barclay, Paul & the Gift [Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2015], 103–4, 121; Timothy Wengert, “Martin Luther on Galatians 3:6–14: Justification by Curses and Blessings,” in Galatians, ed. Elliott et al., 101; Scott Hafemann, “Yaein: Yes and No to Luther’s Reading of Galatians 3:6–14,” in Galatians, ed. Elliott et al., 119). ↩︎

- See e.g., b. Shab. 31a; fuller discussion in Craig S. Keener, The Gospel of Matthew: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2009), 248–49. ↩︎

- Sipra Qed. pq. 4.200.3.7; fuller discussion in Keener, Matthew, 531. ↩︎

- Other Jewish teachers often linked texts based on a common key term or phrase; in this case, both texts in the Torah begin with, “You shall love” (Deut 6:5; Lev 19:18). ↩︎

- The principles of being set apart for God and that even our eating and drinking should glorify God remain, but they are expressed differently. ↩︎

- For four views of the Sabbath, see Charles P. Arand, et al. Perspectives on the Sabbath: 4 Views (Nashville: B&H, 2011). ↩︎

- The text sometimes cited for its abolition (John 5:18) in fact reflects the interpretation of Jesus’s enemies, an interpretation probably subverted in Jesus’s following discourse (see esp. 5:19, 30; further discussion in Craig S. Keener, The Gospel of John: A Commentary, 2 vols. [Grand Rapids: Baker, 2003], 1:645–46). ↩︎

- For two helpful attempts to model a way through the morass, see Willard M. Swartley, Slavery, Sabbath, War and Women: Case studies in biblical interpretation (Scottsdale: Herald, 1983); William J. Webb, Slaves, Women, and Homosexuals: Exploring the Hermeneutics of Cultural Analysis (foreword by Darrell L. Bock; Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 2001). ↩︎

- I chart some of these categories, with similarities and differences, in Keener, Spirit Hermeneutics, 225–30, a work on which I draw in this section. ↩︎

- For some parallels and contrasts, see e.g., Bruce Wells, “Exodus,” in Zondervan Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary: Old Testament, ed. John Walton (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2009), 1:227, 230. ↩︎

- E.g., Hammurabi 196–206 (ANET2, 175). ↩︎

- “Poems about Baal and Anath,” I*AB, v (ANET2, 139); cf. Greco-Roman myth in e.g., Varro, Latin Language 5.5.31. ↩︎

- E.g., Gen 44:5; “Taanach,” 1 (fifteenth century BCE; ANET2, 490); Assyrian “Hymn to the Sun-God” (c. 668–633 BCE; ANET2, 388); Hittite “Investigating the Anger of the Gods” (ANET2, 497–98); “The Telepinus Myth” (ANET2, 128); “Aqhat,” C.2 (ANET, 153); “Akkadian Observations on Life and the World Order” (ANET2, 434). ↩︎

- Cf. similar terminology and sometimes concepts for Canaanite sacrifices, plus some differences, in Allen P. Ross, Holiness to the Lord: A Guide to the Exposition of the Book of Leviticus (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2002), 29; Richard E. Averbeck, “Sacrifices and Offerings,” in Dictionary of the Old Testament: Pentateuch, eds. T. Desmond Alexander and David W. Baker (Downers Grove: IVP, 2003), 712, 715–16, 718, 720; Anson F. Rainey, “Sacrifice and Offerings,” in The Zondervan Encyclopedia of the Bible, rev. ed., eds. Merrill C. Tenney and Moisés Silva (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2009), 5:236–37. ↩︎

- John H. Walton et al., The IVP Bible Background Commentary: Old Testament (Downers Grove: IVP, 2000), 25–26; Roy E. Gane, “Leviticus,” in Zondervan Backgrounds Commentary, 1:287. ↩︎

- For a similar yet limited approach in the rabbis, see David Daube, “Concessions to Sinfulness in Jewish Law,” JJS 10 (1959): 1–13 (esp. 10). ↩︎

- This rule treats the slave better than in some surrounding cultures. See Hammurabi 213–14; Eshnunna 23; also, Roman law in Boaz Cohen, Jewish and Roman Law: A Comparative Study, 2 vols (New York: Jewish Theological Seminary of America Press, 1966), 4. ↩︎

- Though the point could be protecting the slave, since she was abused rather than guilty, it also exempts her abuser from the level of punishment meted out to one who rapes a free person. ↩︎

- Cf. William Sanford LaSor, David Allan Hubbard, and Frederic W. Bush, Old Testament Survey: The Message, Form, and Background of the Old Testament, Second Edition (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1996), 148. ↩︎

- Contrast Deut 23:15 with Eshnunna 49; Lipit-Ishtar 12–13; esp. Hammurabi 15–16. ↩︎

- Probably the Pauline ideal points in this direction; cf. Craig S. Keener and Glenn Usry, Defending Black Faith (Downers Grove: IVP, 1997), 37–41. ↩︎

- E.g., tithes to rulers in 1 Sam 8:15–17; Roland De Vaux, Ancient Israel: Its Life and Institutions, 2 vols., trans. John MacHugh (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1961), 140; corporate, agrarian tithes on Canaanite villages in M. Heltzer, “On Tithe Paid in Grain in Ugarit,” IEJ 25, no. 2–3 (1975): 124–28. Cf. also Greek and Roman usage (e.g., the dedication in Valerius Maximus 1.1. ext. 4; Tertullian, Apologeticus 14.1); for a tithe of grain as tribute to Rome, see Cicero, In Verrem 2.3.5.12; 2.3.6.13–15. For a tenth of military plunder dedicated to deities, see Gen 14:20; Xenophon, Anabasis 5.3.4, 9, 13; Hellenica 4.3.21; Valerius Maximus 5.6.8; Plutarch, Camillus 7.4–5 (for a tenth of plunder offered to a brave warrior, Plutarch, Marcius Coriolanus 10.2). ↩︎