Dead Sea Scrolls

Southwestern Journal of Theology

Volume 53, No. 1 – Fall 2010

Managing Editor: Malcolm B. Yarnell III

Introduction

The past decade has seen a flurry of publications associated with the Dead Sea Scrolls. This scholarly enterprise was also taking place among archaeologists. While the media was debating the nature of the “scholarly conspiracy,” and textual scholars were debating who the scrolls belonged to, there was a rumbling in some parts of the archaeological community over the site of Qumran.

This current debate originated with the questioning of the Essene Hypothesis by a pair of scholars who were enlisted to assist in the publication of the archaeological data. The Donceels interpreted the site as a Villa Rustica (Roman-type villa associated with a rural estate).1 This was the start of various questions and debates concerning the Dead Sea Scrolls and the identification of Qumran. I have isolated three major criticisms concerning Qumran. The first is the “myth” that has developed around Qumran. This is highlighted by a recent paper by Neil Silberman, where he states: “Thus the modern visions of the Dead Sea Scrolls now span the gamut from eschatology to spiritualism, iconoclasm, ecumenism, and patriotic attachments to the State of Israel.”2 Another example of popular culture using Qumran to support their particular story are the many literary works that have sprung up around Qumran. Brenda Levine, in an article covering several works of fiction centered on Qumran and the Dead Sea Scrolls, notes:

The idea that some shocking truth is to be found in these ancient texts which will change or alter present religious beliefs so drastically that church officials must suppress it is still offered by so-called legitimate scholars, as witnessed by some of the allegations during the recent controversy over the long delay in publication of all the scrolls.3

Media hype has also focused on conspiracy theories with the emphasis on power and access to the scrolls.

While these are entertaining trends in popular culture and Qumran, post-processual trends in archaeological research are asking questions such as: Who controls the interpretation of the past? Who tells the story? Is there more than one story? Lester Grabbe, an historian, notes that there is a lack of questions in Qumran studies,

Much of the work on the scrolls has been of a literary nature.

. . . As someone who attempts to be a historian, however, I see some dangers, not only in the present, but also in earlier studies, which can impede progress . . . : 1) an uncritical attachment to a past consensus, 2) a failure to make properly critical historical judgments, and 3) the continued politicization of Qumran Scholarship.4

Some scholars note that Qumran theories (or stories) are not objective but are dependent on the religious or political position of the scholar.5

History of Research

Ironically, most of the results and summaries of the Qumran site were made by textual scholars and not archaeologists. Today, we have the first excavation report by Humbert and Gunneweg. An earlier publication, by Humbert and Chambon in 1994, included a list of photographs and de Vaux’s notes; German and English translations were produced in 1996 and 2003.6

Until these recent publications, the results of de Vaux’s excavations were only published as articles in Revue Biblique and his Schweich lectures. These brief reports were the foundation for the dominant interpretation of the site. Along with G. Lankester Harding, de Vaux began excavations at the site of Qumran in 1951. Excavations continued by de Vaux from 1953 to 1956. The excavations revealed the remains of a well-planned settlement with a complex of buildings, cisterns, pools, canals, and ritual baths. This settlement was built on top of a marl terrace overlooking wadi Qumran. In addition to the settlement, de Vaux excavated at the spring of Ain Feshkah, his last season at Qumran, and then in 1958. This spring is located one and a half miles south of Qumran and served as the nearest source of water.

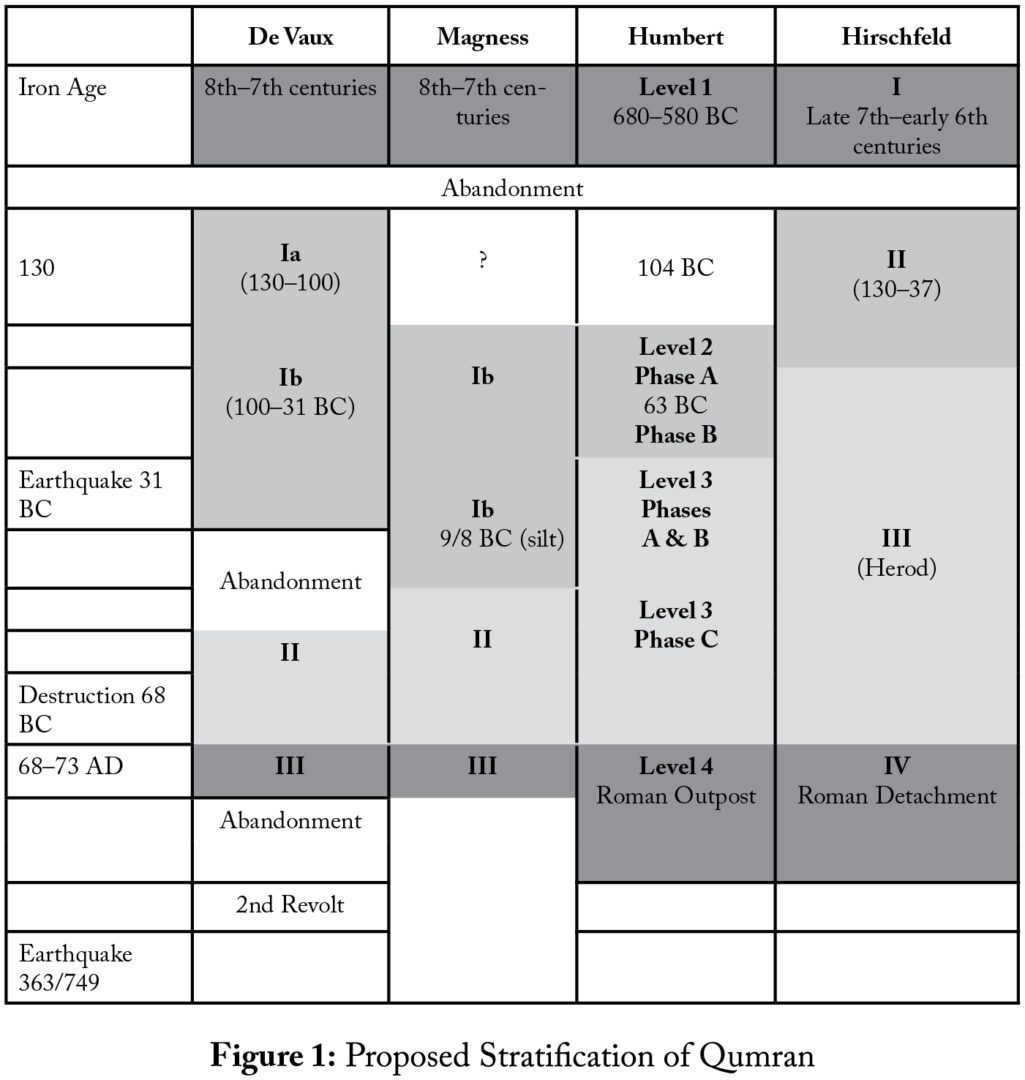

De Vaux divided the site into six main periods of occupation. The first was an Iron Age fort that he dated from the eighth to the sixth centuries BC, when it was abandoned or destroyed. The site was not inhabited again until the Hellenistic Period (1a–b). De Vaux defined two stages. During the first (1b), the remnants of the fort were reused and some mikva’ot were built near the water installation—he dated this phase to the time of John Hyrcanus (134–04 BC). The next phase is the main phase of the settlement, when the central part was expanded to include auxiliary areas and building components: More mikva’ot and reservoirs, a pottery workshop and wine press, dining room and storeroom/pantry, kitchen, scriptorium and storeroom with benches, and a stable. The settlement of this period was destroyed by an earthquake. There was a gap in settlement and sometime around 4 BC the same occupants resettled the site (Roman Period, Period 2). This phase basically reused the settlement after cleaning out some rooms and having some features go out of use. A great quantity of pottery (evidence of the destruction by the Romans in 68 AD) was found. A small Roman garrison occupied the site until 73 AD and made some minor additions. Later, the abandoned buildings served a group of resistance fighters of the Bar-Kokhba Revolt (132–35 AD).

The most important periods were Ib and II—periods associated with the Essene settlement and the Dead Sea Scrolls. This archaeological and historical reconstruction has become solidified in the scholarly community for the past 50 years. This was the story of Qumran and the Dead Sea Scrolls— taught at seminaries and universities throughout the western hemisphere. In some circles, albeit small, scholars are questioning whether this was an accurate portrayal. Since these scholars are very vocal, it has presented us with the impression that we are in a quagmire in regards to the identification of the site.

The past decade saw two conferences on the archaeology of Qumran. One was at the University of Chicago (co-sponsored by the New York Academy of Sciences) in 1992 and the other was held at Brown University in 2002.7 The Brown conference was designed to discuss the latest research on the archaeology of Qumran. An outcome of this conference, as reported by Zangenberg and Galor, was that there needs to be a “sincere discussion on theory formation, on how we create, defend and revise concepts and methods of interpreting the archeological record of Qumran.”8 The authors suggested an incorporation of Hodder’s work on interpretive archaeology or his reflexive archaeology.9

Zangenberg and Galor imply that the archaeological record is like a text with multiple meanings. I would qualify this statement and state that the archaeological record is not multivocal. There is only one voice. We do not find something that is both ceramic and glass, a stone that is worked and unworked. A building is not square-shaped and at the same time oval-shaped. What is multi-vocal are the interpretations of the archaeological record. Multiple interpretations come about because of the nature of the archaeological evidence (fragmentary) and the relationship between culture and the material correlates of society. This is where we find ourselves today in the Qumran quagmire.

While several interpretations of the site have been proposed over the years,10 the debate has now coalesced around two recent books on the archaeology of Qumran. The first is by Jodi Magness,11 in which she supports the Essene sectarian settlement hypothesis. The second is by Yitzhar Hirschfeld, who proposes that Qumran was a fortified estate in a complex settlement system.12

The questions before us today are, “Who is correct?” “Can we arrive at a consensus concerning the interpretation of the archaeological record?” My goal is to provide a synthetic overview of Qumran archaeology and propose that the original Essene hypothesis is supported by the archaeological record, but with some modifications.

Archaeology of Qumran

Recent debates concerning the nature of the settlement at Qumran can be coalesced into four major arenas of data: 1) stratigraphy of the site, 2) Qumran’s place in the Dead Sea region’s settlement hierarchy (definition of the site), 3) interpretation of the various building components, and 4) nature of the material culture (plain pottery versus luxury artifacts).

A. Stratigraphy and Periodization

De Vaux told the story of the site and this became the common interpretation of the excavations. While he was correct in defining the major periods, he did not excavate according to sections and a grid system that would have provided evidence of the subtle shifts in settlement history. Instead, each room received a locus number and this number was retained even when floors and fills were encountered.

Stratigraphic redating has been suggested based on 1) new understanding of numismatic use (e.g. the Herodian period used coins from the Hasmonean period), 2) clearer historical reconstruction of the Hasmonean and Herodian Periods in the Holy Land, particularly in the Judean Desert/ Dead Sea region, and 3) a more developed ceramic chronology and typology of the Hellenistic and Roman periods in the Holy Land. Humbert has noted that we can define stratigraphy based on the expansion of various building components and additions to the main building at the site.

Hasmonean and Herodian Period. All scholars agree that there was a period when Qumran was an Hasmonean compound—either a fortress (Hirschfeld), Hasmonean aristocratic residence (villa rustica), or as de Vaux postulated and Magness supports, it was during this stage that the site was founded as a sectarian community. While I am convinced by Magness’ analysis of the material culture that the site was solely a sectarian community, I am also convinced that there are distinct building phases of the site. Most visitors to the site quickly notice that there is an original square shaped building that is better constructed than an expansion of the settlement to the south and east. I think that Humbert’s proposal best accounts for the sectarian nature of the material culture and the major phases of expansion. He suggests that the settlement was originally an aristocratic Hasmonean residence that was later resettled by a new group of people, the Essenes. The issue is whether or not there was a transformation of the site in the Herodian period.

B. Settlement Hierarchy

Hirschfeld has proposed four major typological groups for settlements in the Dead Sea region during the Second Temple period.13 He has also proposed that there was an extensive road system in the Dead Sea region that supported the commercial interests of these settlements. The first group of settlements are central towns or cities that served as administrative and economic centers of the region. They were established in well-watered oases that allowed for substantial settlements. These are Jericho, ‘En-Gedi, and Zoar. The next set contains the palace complexes. These are large agricultural estates that belong to the upper echelon of society. These sites are Jericho, Masada, and Machaerus, as well as the smaller sites of Alexandrium, Cypros, and Callirrhoe. The third group consists of fortified estates that were a combination of living quarters and agricultural activity. These sites are ‘Ein Feshkha, ‘Ein el-Ghuweir, and ‘En Boqeq—all located along the western coast road of the Dead Sea. The last group includes military forts providing security between these various settlement components. These forts are Rujum el-Bahr, Khirbet Mazin, and Qasr et-Turabeh.

Most scholars who propose that Qumran was a manor palace (villa rustica) place it within this third group of sites. The identification is based on a comparison of building and architectural features, and the nature of the material culture (e.g. interior decoration, pottery, and other finds).

C. Buildings/Architectural Features: Comparison between Manors/ Villas and Qumran

Recent reevaluations (notably Hirschfeld and the Donceels) against the sectarian settlement definition focus on the similarities between Roman manor villas and Qumran. In the recent excavation report, Humbert also holds to this position, but he thinks that this was only during the first part of the Hasmonean settlement and that later it became a sectarian community. The strongest evidence for a manor villa is the morphological similarities14 and architectural elements of stone. Hirschfeld spends a large part of his book on an analysis of the architectural components and concludes that the site is the country estate of a wealthy city dweller, probably a permanent resident of Jerusalem.15 He postulates that there were two parts to the settlement: a pars urbana which is the central part (western part) where the living quarters were located, and the rest of the settlement belonged to the pars rustica, or as he categorizes it, the working farm and industrial area.16 What de Vaux interpreted as the scriptorium (locus 30) with tables for writing, is nothing more than benches, that is, instead of tables, they were probably part of the furniture for a triclinium. The inkwells are part of the writing associated with the commercial enterprises of the estate. The assembly room with a vestibule (locus 4) and the two rooms behind it (loci 1 and 2)17 are storage rooms.

1. Industry. The pars rustica contains all the industrial elements of a working farm. These include the garden (the animal bone deposits are no longer cultic meals but are part of the fertilizer); balsam plant factory with soaking pools-balsam oil for the temple; metal factory (locus 105); a bakery and flour mill (loci 100 and 101); a stable (loci 96 and 97); a stone surface for drying dates; a pottery workshop (loci 64, 80, and 84); and, a wine press (locus 75). A second dining room (locus 77) with its storerooms (loci 86 and 89) served the laborers.

2. Magness and Humbert. Magness associates the architectural and material culture patterning with regions of purity and impurity. Humbert concludes that it is difficult, based on the nature of the archaeological evidence, to define a pattern. He postulates that we can discern horizontal stratigraphy, that is, additions to the settlement as it expanded, although he also concludes that there are visible patterns that should be associated with ritual purity. Basically, the site experienced many stages of additions to the settlement with the addition of architectural units—especially water storage. Nevertheless, even with this “hodge-podge” of additions, there is still a pattern.

3. Water System. Qumran has over ten stepped pools at the site and an elaborate channel system that brings water through the center of the site, feeding the various installations. Even today, when visitors go to the site, they quickly notice the dominance of the mikva’ot and water storage.

When de Vaux originally excavated there were not many mikva’ot known, so he did not associate the stepped pools with this function. Ronny Reich, foremost expert on stepped water installations in the Hasmonean and Roman periods, catalogued approximately 306 in the 1990s; today this number has nearly doubled.18 Hirschfeld notes that the amount of mikva’ot at Qumran is no longer unique and that the pattern is very similar to other desert fortresses and manor houses.

In the final excavation report, Galor provides a complete analysis of the plastered pools. She notes that the water system consisted of 60% mikva’ot and 40% water storage. At other sites in the region with large numbers of mikva’ot, the ratio is reversed. She concludes that the “uniqueness of the stepped pools at Qumran, compared with stepped pools found in other parts of the country, is mostly (1) the total volume of water stored in stepped pools against the volume of water stored in pools without steps, and (2) the individual size of the large-sized pools.”19

4. Cemetery. I will not go into detail here concerning the cemetery. Many articles have been written concerning the osteological data.20 A complete report is now available in Qumran II. It is clear that the cemetery served a settlement and not an extended family. The cemetery reflects simple interment unlike the rich family tombs found throughout the land in the Second Temple period. Even accounting for the grave goods—there is no evidence of wealth when the burials are considered in the context of Second Temple burial practices.

D. Material Culture

1. Stone Work. Proponents of a manor house point to the evidence of interior decoration such as geometric tiles, stucco, number of column drums and bases, several vousoirs (stones from an arch or vault), a console (the springing stone of an arch), a frieze fragment (south of locus 34), a cornice, and flagstone and flooring in the opus sectile technique.

The architectural components that are described as indicative of wealth are common components found for the various supra structures. Column bases, columns, flagstones, and stones used in vaulting arches are needed elements for a multi-storied building. Hirschfeld makes an important distinction, when he states, “On the other hand, some indications of wealth, such as frescoes, mosaic pavements, or a bathhouse are lacking at Qumran.”21

2. Pottery. Jodi Magness has analyzed the pottery from Qumran (unofficially), and has noted some major characteristics of the pottery. The first is the absence of imports. Qumran lacks several types found at contemporary sites in Judea (or they are rare). For instance, there is no eastern terra sigillata as is common in other wealthy estates. Qumran’s assemblage is simple tableware of the late Roman period and the most noticeable feature of the assemblage is the scroll jars. The scroll jars are unique to Qumran (one found at Jericho) but they belong to a corpus of storage vessels (bag shaped) that were probably associated with purity (storage and liquid).

3. Glass. The Donceels focused on the glass and used this to define the wealth of the site. Those who hold to a view that Qumran was a wealthy estate and not a sectarian community have noted that de Vaux does not mention glass in his reports; evidence, they say, that de Vaux was biased in his interpretation of the site.22 The Donceels are to be commended for alerting scholars to the presence of glass at Qumran. In their reports they note that there is an abundance of glass. None of the glass is published, but they note that there are 150 fragments.23 This is used as an example of wealth in the Qumran community. Unfortunately, no one provides any model that determines how much glass separates a poor from a rich settlement.

Hirschfeld analyzed a settlement in the hills above ‘En Gedi and concluded that this was a settlement of hermits.24 He notes that “from the finds it is clear that the lifestyle of the site in both periods was a simple one lacking luxuries.”25 The site is a cluster of cells, possibly housing individuals, who worked the cultivated area of the village of ‘En Gedi. Hirschfeld has also proposed that this is the site of the Essenes “located above ‘En Gedi” as the Pliny account states. This site lacking luxuries contained “approximately one hundred fragments of glass, 44 could be identified typologically.” If a small settlement of hermits had 100 fragments, a larger and more extensively excavated site as Qumran with fifty (50) more fragments does not reflect a “richer” assemblage of glass.26

4. Coins. Coins found at the site are also used as a support by proponents of the wealthy estate model. Coin hoards have been found throughout the Levant, and coins are ubiquitous at all sites. The question is, “How many coins do we need to develop a typology between rich and poor?” Proponents of the wealthy estate model use the presence of coins at Qumran as evidence that these were not poor sectarian inhabitants. Archaeologists and historians need to determine at what point is a site considered wealthy, based on the presence or absence of coins. This is an important methodological point that needs to be addressed. Once an appropriate model is developed to determine the amount of coins to habitation and the identification of a site as wealthy, the coins of Qumran can properly be used for a reconstruction of the site. Another issue is that the settlement was almost completely excavated, a methodology that is not utilized by most field projects today. Any comparison between the site of Qumran and other sites needs to take into account that a majority of sites are no longer completely excavated.

Summary of Archaeology

The debate centers on the definition of religious features versus commercial and/or industrial components on the site. Is Qumran a commercial site with religious components (e.g. balsam for the temple) or a religious community with household industry? Those scholars who interpret the archaeological data as evidence of an economic settlement—either as an economic entropot or as a wealthy patrician family capitalizing on the resources of the Dead Sea region—must show that this was the primary function of the site. In actuality all the finds associated with economic activity (agricultural plots and terraces, pottery kiln, metallurgy, etc.) are not the dominant features, but are commonly shared building elements and features found at all settlements. The major features of the settlement are cultic, such as the vast ritual bath system. The debate will continue over the scriptorium, a couple of ink wells, and these strange plastered benches. They are difficult to be used as writing tables, benches, or tables for trincliniums.

Scholars who identify the site as a wealthy aristocratic estate, instead of the “simple” impoverished Essene community, base their interpretation on the presence of glass, architectural components, and luxury ware pottery. Those who want to identify the material culture of Qumran as belonging to a wealthy manor need to provide the comparative analysis between the material culture assemblages of sites such as Jericho or Ramat Hanadiv with Qumran, not simple statements of the presence or absence of items. The supposed architectural components alluding to wealth have now been published (capitals, opus sectile, etc.) and are found to be minor when compared to other sites. The pottery that has been published demonstrates that there is no “smoking gun” of luxury ware that is going to reveal that the inhabitants were wealthy, such as the Herodian mansions excavated in the Jewish Quarter. Even the supposed “imported pottery” and luxury ware mentioned by the Donceels (surprisingly, not published) and the recent excavations by Magen and Peleg (as reported at the Brown conference) are not enough to change the interpretation of the material culture. Archaeologists no longer use the simple equation of the presence or absence of a diagnostic type to define an assemblage. They now look at the entire assemblage and statistical patterning to make inferences about the material culture.

Has anything changed? Will archaeology present a different picture? I would think not. Even with the material culture that has not yet been published, I do not think there will be any shift in the current association of this as a site of a religious community.

Conclusion

While I disagree with Hirschfeld’s identification of Qumran as a villa, he provides an important theoretical approach to the identification of the site. Qumran has always been interpreted within de Vaux’s Sectarian Essene community. While much is made of de Vaux’s catholic and priestly background in the interpretation of the site by recent post-processual critiques, it is fair to reevaluate the Essene-Monastic community hypothesis. Humbert addresses this issue in his introduction to Qumran II, where he notes that Qumran is one of the few archaeological sites that is interpreted by the textual record and not by the archaeological data.27

Hirschfeld does a service by placing the Qumran settlement in the context of other sites, and archaeologists need to evaluate and interpret the site as we do with all other sites: 1) typological and comparative methodology that is based on the material culture, and 2) define the site within its larger settlement context. But as Magness illustrates in her work, even putting Qumran in its context demonstrates that the site is unique. While there are several architectural components (aqueducts, fortifications, layout) that are similar at other sites, notably manor houses, these reflect the common technology and architectural knowledge of the Hasmonean-Early Roman period and not necessarily similar settlement type. Other factors—such as the large cemetery, the scroll caves, the large mikva’ot system, and the communal rooms—suggest a settlement that is more akin to a small communal group rather than a rich patrician house with an extended family.

Qumran is one of the best examples of using text, historical sources, and archaeological evidence to reconstruct the past. While the interpretation has been questioned recently, the consensus remains that this was a sectarian community. One of the problems with the recent debate is the nature of the discussion. Scholars have framed the question as to whether you accept or reject de Vaux’s interpretation of the site. In the larger debate over the association of the site with the Essenes, the question is proposed the same way. The methodology of the discussion should not create an antithesis between text and archaeology, but use each dataset (text, archaeology, historical sources) to reconstruct the past. We conclude with some summary statements regarding past demonstrations and future avenues for investigation.

What Has Archaeology Demonstrated?

- History of the site: Magness, based on the ceramic data, and Humbert, based on the stratigraphic analysis of the development of the site, have shown that there was no gap as de Vaux originally proposed.

- Hasmoneans probably built a fort/settlement here.

- During the Herodian period, the Essenes were able to take possession or occupy the “settlement.” This implies some relationship between Herod and the Essenes.

- As with any religious community, there is always a tension between orthodoxy and orthopraxy. While the community’s writings shed light on their orthodoxy, their beliefs and assumptions about what is correct practice, archaeology provides a glimpse into what they were actually doing.

- The caricature of the Essenes created by the sources ( Josephus and Pliny) and “canonized” by scholars must be changed. This was not a community of celibates, forsaking society, poor vagabonds, but one of many groups. This group was probably a fundamentalist strand that rejected the status quo: Religious authority of the Pharisees and the Hellenization of the Sadducees and Herodians.

Possible Avenues for Future Investigation

Naturally, one of the questions is the identification of Qumran with a sectarian community living in the desert. We do not have any contemporary communities in the early Roman period (63 BC–135 AD). We do have several monastic communities in the Byzantine period to test the material culture of this type of community. Magness refers to this comparison in her discussion on women at the site (Chapter 8). I find it interesting that Hirschfeld, one of the foremost experts on the monastic communities of the Judean Desert, does not provide a comparative analysis of Qumran with late Roman-Byzantine desert settlements. If he did, I am confident that he would find similar architectural and settlement features as well as similar patterns in material culture.

Hirschfeld should have expanded his contextual-archaeology approach and placed Qumran in its regional and sociological context. The Judean Desert has always served as a retreat among cultists. Ever since the Chalcolithic period this region has served religious zealots. In the later period, this region becomes dominated by religious communities, the desert monasteries. Qumran in context demonstrates that the dominant interpretation of the site as a sectarian community is supported by the archaeological record. The desert is a region to escape the world and place your life in total devotion to God.

- R. Donceel and P. Donceel-Voûte, “The Archaeology of Khirbet Qumran,” in Methods of Investigation of the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Khirbet Qumran Site: Present Realities and Future Prospects, ed. Michael O. Wise, et al. Annuals of the New York Academy of Sciences 722 (New York: New York Academy of Sciences, 1994), 1–32. ↩︎

- Neil Asher Silberman, “The Scrolls as Scripture: Qumran and the Popular Religious Imagination in the Late Twentieth Century,” in The Dead Sea Scrolls: Fifty Years After Their Discovery, ed. Lawrence H. Schiffman, et al. ( Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 2000), 925. ↩︎

- Brenda Lesley Segal, “Holding Fiction’s Mirror to the Dead Sea Scrolls,” in The Dead Sea Scrolls: Fifty Years After Their Discovery, ed. Lawrence H. Schiffman, et al. ( Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 2000), 906. ↩︎

- Lester L. Grabbe, “The Current State of the Dead Sea Scrolls: Are There More Answers than Questions?” Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha: Supplement Series 26 (1997): 54. ↩︎

- Charlotte Hempelm, “Qumran Communities: Beyond the Fringes of Second Temple Society,” Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha: Supplement Series 26 (1997): 44–53. ↩︎

- Jean-Baptiste Humbert and Jan Gunneweg, eds., Khirbet Qumrân et ‘Aïn Feshkha. Vol 2: Études d’anthropologie, de physique et de chimie. Novum Testamentum et Orbis Antiquus, Series Archaeologica 3 (Freiburg: Academic Press Fribourg, 2003); Jean-Baptiste Humbert and Alain Chambon, eds., Fouilles de Khirbet Qumrân et de Aïn Feshkha. Vol 1: Album de photographies. Répertoire du fonds photographiques. Synthése des notes de chantier du Pére Roland de Vaux, Novum Testamentum et Orbis Antiquus, Series Archaeologica 1 (Freiburg: Academic Press Fribourg, 2003); Roland de Vaux, Die Ausgrabungen von Qumran und En Feschcha. Die Grabungstagebücher. Deutsche Übersetzung und Informationsaufbereitung durch Ferdinand Rohrhirsch und Bettina Hofmeir, Novum Testamentum et Orbis Antiquus, Series Archaeologica 1A, trans. and suppl. Ferdinand Rohrhirsch and B. Hofmeir (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1996); J.-B. Humbert and A. Chambon, The Excavations of Khirbet Qumrân and Ain Feshkha: Synthesis of Roland de Vaux’s Field Notes, trans. and rev. Stephen J. Pfann, Novum Testamentum et Orbis Antiquus, Series Archaeologica 1B (Freiburg: Academic Press Fribourg, 2003). ↩︎

- Wise, Methods of Investigation of the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Khirbet Qumran Site; and Katharina Galor, Jean-Baptiste Humbert, and Jürgen Zangenberg, eds., Qumran, The Site of the Dead Sea Scrolls, Archaeological Interpretations and Debates: Proceedings of a Conference held at Brown University, November 17–19, 2002, Studies on the Texts of the Desert of Judah 57 (Boston: Brill, 2006). ↩︎

- J. Zangenberg and K. Galor, “Qumran Archaeology in Transition,” Qumran Chronicle

11 (2003): 1–6. ↩︎ - Ian Hodder, The Archaeological Process: An Introduction (Oxford: Blackwell, 1999); Idem, ed., Towards Reflexive Method in Archaeology: The Example at Çatalhöyük (Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2000). ↩︎

- Magen Broshi and Hanan Eshel,“Qumran and the Dead Sea Scrolls: The Contention of Twelve Theories,” in Religion and Society in Roman Palestine: Old Questions, New Approaches, ed. Doug R. Edwards (London: Routledge, 2004), 162–69. ↩︎

- Jodi Magness, The Archaeology of Qumran and the Dead Sea Scrolls (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002). ↩︎

- Yizhar Hirschfeld, Qumran in Context: Reassessing the Archaeological Evidence

(Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2004). ↩︎ - Ibid., 221. ↩︎

- Humbert, Khirbet Qumrân et ‘Aïn Feshkha. ↩︎

- Hirschfeld, Qumran in Context, 242. ↩︎

- Ibid., 93, 100, 143. ↩︎

- Stegemann interprets these rooms as a library reading room with scroll storage. H. Stegemann, The Library of Qumran: On the Essenes, Qumran, John the Baptist, and Jesus (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998), 39–40. ↩︎

- K. Galor, “Plastered Pools: A New Perspective,” in Khirbet Qumrân and ‘Aïn Feshkha,

291–320, ↩︎ - Ibid. 310–13. ↩︎

- Zdzislaw Jan Kapera, “Some Remarks on the Qumran Cemetery,” in Methods of Investigation of the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Khirbet Qumran Site, 97–113; Joseph Zias, “The Cemeteries of Qumran and Celibacy: Confusion Laid to Rest?” Dead Sea Discoveries 7 (2000): 220–53; Idem, “Qumran Archaeology Skeletons with Multiple Personality Disorders and Other Grave Errors,” Revue de Qumran 21 (2003): 83–98; Hanan Eshel, et al., “New Data on the Cemetery East of Khirbet Qumran,” Dead Sea Discoveries 9 (2002): 135–65; Susan Sheridan, “Scholars, Soldiers, Craftsmen, Elites? Analysis of French Collection of Human Remains from Qumran,” Dead Sea Discoveries 9 (2002): 199–248; Joan Taylor, “The Cemeteries of Khirbet Qumran and Women’s Presence at the Site,” Dead Sea Discoveries 6 (1999): 285–323; Jürgen Zangenberg, “Bones of Contention: ‘New’ Bones from Qumran Help Settle Old Questions (and Raise New Ones)—Remarks on Two Recent Conferences,” The Qumran Chronicle 9 (2000): 51–76; Zdzislaw J. Kapera and Jacek Konik, “How Many Tombs in Qumran?” The Qumran Chronicle 9 (2000): 35–49. ↩︎

- Interestingly, the Donceels and Hirschfeld mention opus sectile at the site, but in the excavation report, opus sectile was found only at Ein Feshka. ↩︎

- Donceel and Donceel-Voûte, “The Archaeology of Khirbet Qumran,” in Methods of Investigation of the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Khirbet Qumran Site, 1–32. ↩︎

- Ibid., 24–25. ↩︎

- Yizhar Hirschfeld, “A Settlement of Hermits above ‘En Gedi,” Tel Aviv 27 (2000): 103–55. ↩︎

- Ibid., 13. ↩︎

- The site was excavated by Aharoni in 1956, so the variable of collection strategies and archaeological method is null. ↩︎

- Jean-Baptiste Humbert, “Reconsideration of the Archaeological Interpretation,” in

Khirbet Qumrân et ‘Aïn Feshkha, 419–38. ↩︎