Theology Applied

Southwestern Journal of Theology

Volume 63, No. 1 – Fall 2020

Editor: David S. Dockery

Thankfully, God sees to it that in every generation there are those faithful preachers who have not bowed the knee to culture and choose to preach the Bible. As one who has listened to preaching for more than 55 years, practiced it for 45 years, studied it for more than 35 years, and taught it for more than 30 years, I am always thankful for those who faithfully preach the Word.

Sadly though, some of today’s American pulpit is a hodge-podge of mediocrities, curiosities, and even some atrocities.

I have heard texts eisegeted rather than exegeted. I have seen preachers skirmish cleverly on the outskirts of a text, yet never get to its meaning and thrust. I have witnessed sermonic magic shows where a preacher keeps reaching into an empty hat and extracting a handful of nothing. I have heard texts bludgeoned and battered, twisted and tortured into submission. I have sometimes felt when the preacher completed his sermonic surgery, he failed to rightly divide the Word of truth, and I half hoped that the text would rise up and sue the negligent preacher for exegetical and theological malpractice.

In some churches, the dearth of genuine biblical preaching seems obvious. Theologian J. I. Packer called it “nonpreaching.” Any number of sermonic idols, including entertainment, personal experience, packaged pragmatism, pop psychology, social gospel, self-help therapy, five-ways-to-be-happy, and three-ways-to-love-your-mother kind of preaching displace the Bible on any given Sunday. In Packer’s words:

Not every Discourse that fills the appointed 20- or 30- minute slot in public worship is actual preaching, however much it is called by that name. Sermons (Latin, sermons, “speeches”) are often composed and delivered on wrong principles. Thus, if they fail to open Scripture or they expound it without applying it, or if they are no more than lectures aimed at informing the mind or addresses seeking only to focus the present self-awareness of the listening group, or if they are delivered as statements of the preacher’s opinion rather than as messages from God, or if their lines of thought do not require listeners to change in any way, they fall short of being preaching, just as they would if they were so random and confused that no one could tell what the speaker was saying.1

In the midst of today’s “cancel culture” movement, some preachers’ sermons indicate they are members of the “cancel Scripture” movement. Their sermons contain everything but the Word. Of course, the obligatory text is given lip service at the beginning of a sermon, but quickly falls by the wayside as the preacher straightway departs therefrom.

The absence of biblical preaching results in doctrine being watered down or ignored. Instead of a robust diet, people are fed spiritual junk food. The sheer weightlessness of such preaching is astounding. No wonder so many spiritual teeth are decaying. The sheep look up and are not fed.

Many mainline denominations have abandoned biblical authority. Caught in the cul-de-sac of a post-liberal Barthian bibliology with its never-ceasing erosion of biblical authority,2 the first casualty is the pulpit. The failure of the New Homiletic is a case in point.3 With the publication of Fred Craddock’s As One Without Authority in 1971, the New Homiletic was born. It was quickly followed by “narrative preaching.” Generally speaking, these movements consider the notion of linear thinking to be passé. In the New Homiletic, this concept exhibited itself in the idea that the goal is not so much on hearing the truth as it is on experiencing the truth. Craddock initiated a move away from the so-called “deductive, propositional” approach to preaching to a more inductive approach. The goal is to create an experience in the listener which effects a hearing of the gospel. The sermon becomes a communication event in which the audience along with the preacher co-creates the sermonic experience.4

However, the problem with the New Homiletic is its elevation of the audience over the text, and its privileging of experience over knowledge. Instead of exposition, the sermon proceeds in a narrative form that oftentimes leaves the meaning of the text blurred or undeveloped. This is not to say that the New Homiletic has nothing to teach us about preaching, for indeed it does. However, due to the truncated view of biblical authority of many of its practitioners, the New Homiletic does not take seriously enough the text of Scripture itself as God’s Word to us.

Having determined that traditional propositional preaching was inadequate, practitioners opted for indirect communication as a preaching strategy. Unfortunately, wedded to Barth’s bibliology, their approach has not yielded the anticipated result, and now many within the New Homiletic recognize the need for adjustment.5

Evangelical denominations and churches have not escaped unscathed. Evidence suggests the need to rethink the importance of biblical authority and its concomitant doctrine of inerrancy, coupled with a strong commitment to the sufficiency of Scripture in our preaching. The inerrancy of Scripture is still affirmed in the majority of evangelicalism, but even here there has been significant erosion over the past twenty years.6 While the battle for the inerrancy of Scripture will remain ongoing, today’s evangelicals are engaged in a new battle: the sufficiency of Scripture in preaching. Is the Bible, and the Bible alone, sufficient to change hearts and grow a church? Hundreds of preachers give lip service to inerrancy, but by the conferences they attend and the sermons they preach, they demonstrate that their heart is far from the sufficiency of Scripture.

John Stott insightfully commented that the essential secret of preaching is not “mastering certain techniques, but being mastered by certain convictions.”7 All preaching rests upon certain convictions about the nature of God, the Scriptures, and the gospel. Haddon Robinson is correct when he pointed out: “Expository preaching, therefore, emerges not merely as a type of sermon – one among many – but as the theological outgrowth of a high view of inspiration. Expository preaching then originates as a philosophy rather than a method.”8 All preaching, regardless of the form it takes, should be expositional in nature. The word “homiletics” itself etymologically derives from the Greek word homo meaning “same,” and “legō, meaning “to speak.” Homiletics is the art and science of sermon construction and delivery that says the same thing that the text of Scripture says.9

If the mission of the church is the evangelism of the lost and the equipping of thesaved, then of all things the church does, should not preaching to be at its apex? One will notice the differences between Matthew and Mark in the giving of the Great Commission. Whereas Matthew 28:19 speaks of going into all the world and “making disciples,” Mark 16:15 says “Go into all the world and preach the gospel.” Obviously preaching plays a paramount role in the church’s mandate to fulfill the Great Commission.

I. PREACHING AS FOUNDATIONAL: NATURE AND SOURCE OF SCRIPTURE

There are several reasons why preaching is foundational for the mission of the church. The first reason is theological: the nature and source of Scripture. Scripture is the Word of God. In Scripture, God speaks. From Genesis to Revelation, God is a God who speaks. The Word of God is inscripturated. The Word of God is also incarnated: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God and the Word was God” (John 1:1): “God, having spoken of old in different times and in different ways to the fathers by the prophets, has in these last days spoken to us in His Son” (Hebrews 1:1–2).

God has spoken in Christ and in Scripture. In no other way could we know him. Though the universe declares the glory of God and bears witness to his power, it could never tell us of his love. Though history tells us of the sovereignty of God, it can never fully explain what Christ accomplished on the cross. Though our conscience bears witness to the morality of God, it can never teach us how to live and love rightly. Unless God speaks, we would never know him or his love for us. To us, the universe, history, and conscience are all one great undecipherable hieroglyph until we discover God’s Rosetta Stone—Jesus the living Word and Scripture the written Word.

God is the perfect communicator. Jesus is God’s perfect communication to us. Jesus is God’s ultimate communication because he is God’s perfect representation. Jesus perfectly represents God because he is a member of the Trinity and Scripture perfectly represents Jesus. Jesus is God spelling himself out in language we can understand. Jesus does not reveal something other than himself, nor does he reveal something other than God: “The word became flesh and dwelt among us. We behold his glory, even the glory of the only Son from the Father…No one has ever seen God; the only Son, Jesus, has made him known” (John 1:14, 18). Jesus is the speech of eternity translated into the language of time. The inaudible has become audible. The invisible has become visible. The unapproachable has become accessible. God’s revelation in Jesus is personal, plenary, and permanent, and God’s revelation in the written Word is plenary and permanent.

God’s perfect communication in Christ and in Scripture has as its goal the salvation of all sinners. Therefore, Paul admonished Timothy to “preach the Word” (2 Tim 4:1–2). The first theological foundation for preaching is this fact: God has spoken!

II. PREACHING AS FOUNDATIONAL: DIVINE AUTHORITY

A second reason why preaching is foundational for the church is its divine authority. As the Word of God, Scripture is inspired, inerrant, and sufficient according to 2 Timothy 3:16–17: “All Scripture is God-breathed, and is profitable for doctrine, reproof, correction and instruction in righteousness.” The authority of Scripture is the very authority of God.

Jesus is the living Word and Scripture is God’s written Word. God is the ultimate author of all Scripture according to 2 Timothy 3:16. It is noteworthy how New Testament authors quote the Old Testament. Often, God and Scripture are interchangeable terms via metonymy when quoting the Old Testament. For example, God is viewed as the author when he himself is not the speaker, as in Matthew 19:4-5. On the other hand, “Scripture says” is used when God himself is the direct speaker, as in Romans 9:17, Galatians 3:8 and 22. To J. I. Packer once again: “Scripture is God preaching.”

The Old Testament quote formulae in Hebrews are instructive. Hebrews not only views Jesus as God’s speech to us, but Hebrews views Scripture as the speech of the Trinity (Heb 1:5-13; 2:12-13; 3:7). Jesus links himself to the Old Testament throughout his ministry. In Luke 4:14–30, when Jesus preached, he took a text of Scripture from Isaiah and startled his synagogue hearers by applying it to himself and claiming its fulfillment on that very day (Isa 61:1-2) After his resurrection, while walking with the two disciples on the road to Emmaus, he chided them for their unbelief and laid the fault at the feet of their failure to consider the Scriptures. He then referenced the three sections of the Hebrew Bible—the Law, the Prophets, and the Writings—and asserted that each “testified” concerning himself.

Paul’s method of evangelistic preaching according to Acts 17:2–3 is informative: “As was his custom, Paul went into the synagogue, and on three Sabbath days he reasoned with them from the Scriptures, explaining and proving that the Messiah had to suffer and rise from the dead.” Paul’s New Testament letters to the churches are mostly written sermons. They contain what Paul would have preached to them had he been with them in person. Hebrews is itself a written sermon that develops several Old Testament texts of Scripture, Psalm 110:1 and 4 being primary.

Our authority for preaching comes from God himself and from his word, Scripture. As Haddon Robinson reminds us, “Ultimately the authority behind preaching resides not in the preacher but in the biblical text.”10 As the Second Helvetic Confession states, “The preaching of the word of God is the word of God.”

Thus, to preach, kerussō, is an authoritative public proclamation of Jesus the Word and Scripture as the word of God. First Thessalonians 2:12–13 makes clear that the source and authority for preaching is God himself: “For this reason we also constantly thank God that when you received the word of God which you heard from us, you accepted it not as the word of men, but for what it really is, the word of God, which also performs its work in you who believe.”

III. PREACHING AS FOUNDATIONAL: DIVINE CONTENT

A third reason why preaching is foundational for the mission of the church is its divine content. In 2 Timothy, Paul admonished young Timothy to “preach the word” (2 Tim 4:2). In context, the word is the written Scripture of 2 Timothy 3:16–17. Preaching is the ministry of the word and should be shaped by the nature of the word. The focus here is on preaching to the church, as evidenced by context and the use of “teaching” in the final phrase.

Jesus critiques the misreading of Scripture on five occasions, in each chiding the Jewish leaders: “Have you not read?” Perhaps Jesus critiques our mis-preaching of Scripture. Next to a lack of truth, a sermon’s greatest fault is lack of biblically developed content. Preaching must be “text-driven” and “Christ-centered.” It cannot be the latter unless it is first the former.

Luke records Paul’s approach in his evangelistic preaching in Acts 17:2–3: “And according to Paul’s custom, he went to them, and for three Sabbaths reasoned with them from the Scriptures, explaining and giving evidence that the Christ had to suffer and rise again from the dead.” Perry and Strubhar are correct: “The biblical text must be the foundation of every evangelistic sermon.”11

Since God himself speaks in and through Christ and Scripture, it is incumbent on preachers to expound the meaning of Scripture to their people. In so doing, they are preaching Christ through the very words of God, Christ, and the Holy Spirit in Scripture. To preach the Word is to hear Christ and encounter him.

We are not just preaching sermons; we are preaching texts— inspired texts. The word “text” comes from the Latin word meaning “to weave.” The word figuratively expresses thought in continuous speech or writing. The product of weaving is the textus in Latin. It is a linguistic composition expressed orally or in writing. A text is a cohesive and structured expression of language that intends a specific effect.12

Biblical preaching should be the development of a text of Scripture: its explanation, illustration, and application. Our focus should not only be on what the text says, but as much as is possible, on what the author is trying to do with his text—what linguistics call “pragmatic analysis.”

One of the goals of preaching is to communicate the meaning of the text to an audience in terms and contexts they understand. One way to think about preaching is to view it as a form of translation. We are translating the meaning of our text to our audience. The word “translate” comes from the Latin word meaning “to transfer.” In a sense, we are “transferring” meaning. And meaning is fragile. Freight may be altered or damaged in shipment. We must handle with care.

Many a sermon uses a text of Scripture but is not derived from the text. In such a sermon, the text is not the source of the sermon; rather, it is only a resource. For some preachers, the Bible is something of a happy hunting-ground for texts on which to hang what they want to say to the people. G. Campbell Morgan spoke of one preacher whose habit was to write his sermons and then choose a text as a peg on which to hang them. Morgan went on to say that the study of that preacher’s sermons revealed the peril of the method. At times, a sermon can sound like a marauding horde of undisciplined thoughts or a loose kind of omnium-gatherum of vague generalities. On the other hand, some preachers dazzle us with a blinding flash of swordplay almost too fast to follow. Such preaching may be clever and ingenious, but merely evinces a superficial connection with the text of Scripture. Preaching is not just playing with the subject of your text as one observer said of Lancelot Andrewes’ preaching in the court of King James I: “don’t play with the text; preach the text.” Kent Hughes talks about a kind of preaching he calls “disexposition.” Disexposition occurs when the preacher takes a text but promptly departs therefrom in the sermon. Disexposition occurs when, no matter the text of Scripture, the sermon sounds the same. Disexposition occurs when preaching is “decontexted” (that is, it shows no regard for context). There are few sentences in Hebrews or the first eleven chapters of Romans which can be fully understood without having in mind the entire argument of the Epistle, as John Broadus and others have rightly noted. Disexposition also occurs when a text is “lensed,” as in sermons always focused on pet peeves or themes—domestic, political, ethical, etc., as well as “moralized,” as when Philippians 3:13 is preached as an exhortation in setting personal goals. Luther spoke of an allegorical preaching as an exegetical alchemy that sets out to turn lead into gold but ends up turning gold into lead. You cannot preach the word right until you cut it straight.13 Walter Brueggmann said preachers are scribes who are entrusted with texts. In the same way that the scribes worked meticulously to handle the text, so preachers must meticulously exegete the text to determine its meaning and faithfully represent that meaning to the people.

Genuine expository preaching is text-driven preaching. Text-driven preaching attempts to stay true to the substance, the structure, and the spirit of the text.14 The “substance” of the text is what the text is about or its theme. The “structure” of the text concerns the way in which the author develops the theme via syntax and semantics. A text has not only syntactical structure but also semantic structure, and the latter is what the preacher should be attempting to identify and represent in the sermon.15 The “spirit” of the text concerns the author’s intended “feel” or “emotive tone” of the text which is influenced by the specific textual genre, such as narrative, expository, hortatory, poetic, etc.16

Unfortunately, some preachers subordinate the text to their sermon. This becomes evident when preachers preach sermons filtered through preconceived doctrinal systems that sometimes are imposed upon the text. Other preachers subordinate the text to their application in the sermon. You cannot have legitimate application until you first have exposition of textual meaning that grounds the application. Scripture links exegesis and application. The book of Hebrews is a perfect example. There is a boundary between exegesis and application, but it is a permeable boundary. Truth is unto holiness as my professor, Robert Longacre, used to say.

John Broadus reminds us all that we must delight in the exegetical study of the Bible to succeed in expository preaching; we must love to search out the exact meaning of its paragraphs, sentences, phrases, and words.17 Exegesis of Scripture is the foundation of our exposition of Scripture in preaching. Exegesis is homiletical because preaching is text-based and thus meaning-based. “Faithful engagement with Scripture is a standard by which preaching should be measured, and the normal week-in, week-out practice of preaching should consist of sermons drawn from specific biblical texts.”18

Exegesis must be the first language of the preacher; biblical theology, his second language; and systematic theology, his third language. Most preachers, instead of expounding the text, skirmish cleverly on its outskirts. Much of today’s preaching is pirouetting on trifles rather than expounding the text. Without a text to ground the sermon, the preacher becomes something of a magician who, with conjuring adroitness week after week, keeps producing rabbit after rabbit out of an obviously empty hat.

Text-driven preachers are not just preaching sermons; we are preaching texts in an effort to communicate accurately God’s meaning to the people. The text gets the first word. The text gets the last word. There is a bond between Scripture and sermon. People encounter God not outside the text of Scripture but through the text of Scripture. Our response to the word is our response to Christ. The stream of the sermon will never run clear if the source of the sermon is other than a text of Scripture.

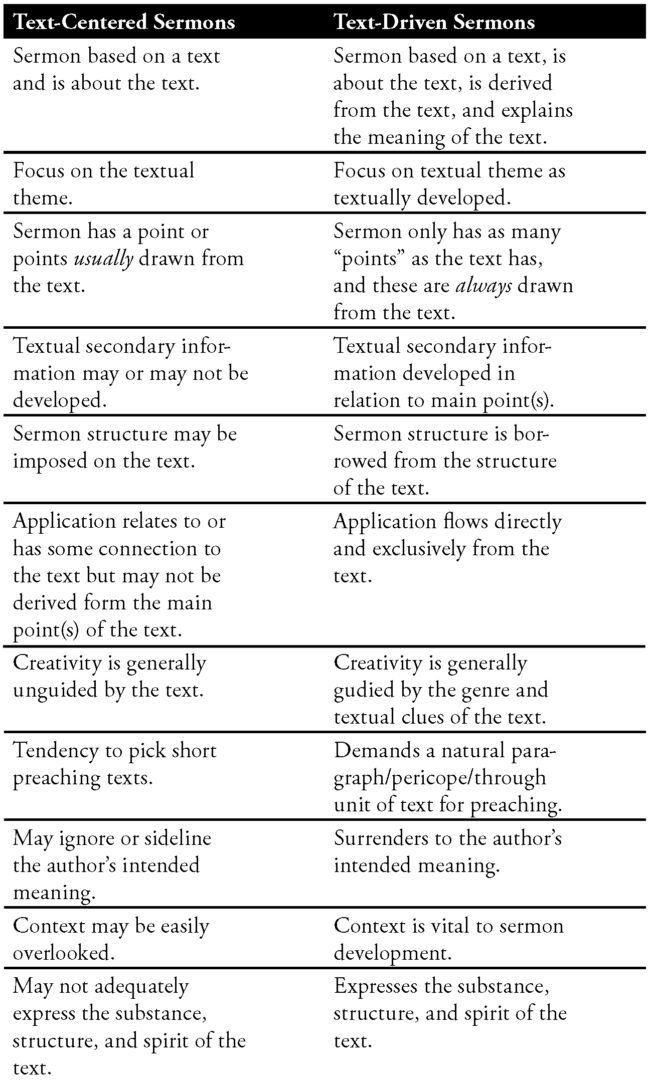

1. Text-centered vs. Text-driven. Many sermons fall under the rubric of “expository” and are thus text-centered, but not necessarily text-driven. What is the difference between a sermon that is “text-centered” and one that is “text-driven”? Perhaps the following chart will be helpful in drawing distinctions.

2. Linguistics and Preaching: Semantic Structure of Texts. It is this foundation for preaching in the mission of the church, the divine content, that ineluctably leads to the necessity of exegesis before sermon preparation. From a linguistic perspective, the importance of the study of the semantic structure of texts is vital to genuine biblical preaching. We must strive to examine not only the form but also the meaning of all levels of a text with the goal of understanding the whole.19

The painstaking work of exegesis is the foundation for text-driven preaching.20 Exegesis precedes theology and theology is derived from careful exegesis. To preach well, it is vital to understand certain basics about the nature of language and meaning. Enter linguistics.

From a linguistic perspective, text-driven preaching should correctly identify the genre of the text. Longacre identified four basic discourse genres which are language universal: narrative, procedural, hortatory and expository.21 All four of these genres, along with subgenres, occur in Scripture. Significant portions of the Old Testament are narrative; the Gospels and Acts are primarily narrative in genre. Procedural discourse can be found in Exodus 25–40 where God gives explicit instructions on how to build the tabernacle. Hortatory genre is found in the prophetic sections of the Old Testament as well as in the epistolary literature of the New Testament, though it is by no means confined to these alone in the Scriptures. Expository genre is clearly seen in the New Testament Epistles, each of which are combinations of expository and hortatory genre.

Semantic analysis of a text looks beyond words and sentences to the whole text. Every biblical text is an aggregate of relations between the four elements of meaning which it conveys: structural, referential, situational, and semantic. Referential meaning is that which is being talked about or the subject matter of a text. Situational meaning is information pertaining to the participants in a communication act (matters of environment, social status, etc.). Structural meaning has to do with the arrangement of the information in the text itself, that is the grammar and syntax of a text. Semantics has to do with the structure of meaning and is in some sense the confluence of referential, situational, and structural meaning.22

Homiletics has focused on the first three of these elements to the exclusion of the semantic. Analyzing a text’s semantic structure allows one to see the communication relations within the text in their full extent. Restricting exegesis to a verse-by-verse process alone often results in the details of the text overshadowing the overall message. It becomes hard to see the forest for the trees, and this oversight is often transferred to the sermon as well.

Linguists now point out the fact that meaning is structured beyond the sentence level. When the preacher restricts the focus to the sentence level and to clauses and phrases in verses, there is much that is missed in the paragraph or larger discourse that contributes to the overall meaning and interpretation of the text. The paragraph unit is best used as the basic unit of meaning in expounding the text of Scripture. Ideally, text-driven preaching should deal with a paragraph (as in the Epistles) at minimum; while in the narrative portions of Scripture, several paragraphs which combine to form the story (pericope) should be treated in a single sermon since the meaning and purpose of the story itself cannot be discerned when it is broken up and presented piecemeal. Text-driven preaching looks beyond words and sentences to the whole text (paragraph level and beyond).

The hierarchy of language is such that words are combined into larger units of meaning. Words combine to form phrases; phrases combine to form clauses; clauses combine to form sentences; sentences combine to form paragraphs; and paragraphs combine to form discourses. When it comes to a text of Scripture, however long or short, the whole is more than just the sum of its parts.

Language makes use of content words and function words. Content words are such parts of speech as nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs. Function words are articles, prepositions, and conjunctions. Content words derive their basic meaning from the lexicon of the language. Function words derive their functional meaning from the grammar and syntax of the language. Of course, lexicon, grammar, and syntax combine to give content words and function words their meaning in a text. It is especially important in text-driven preaching to pay close attention to the function words in a text. For example, the Greek conjunction gar always introduces a sentence or a paragraph that is subordinate to the one preceding it,23 and usually signals that what follows will give the grounds or reason for that which precedes. This is immensely important in exegesis and sermon preparation.

Language employs a verbal structure. Verbs are the load-bearing walls of language. Understanding their function within the text is vital to identifying the correct meaning which the author wants to convey.24 Hence, I recommend the discipline of “verb charting” during the exegesis phase of sermon preparation. In Greek, for example, so much information is encoded in the verb (tense, voice, mood, person, number, and lexical meaning). Identifying the main clauses and subordinate clauses in a text is crucial for identifying the semantic focus of the author.25

Most of us are trained to observe structural meaning; we are intuitively aware of referential meaning and situational meaning, but we often fail to observe the semantic structure of a text. The text-driven preacher will want to analyze carefully each one of these aspects of meaning for a given text.

John 1:1 furnishes an example of the importance of lexical meaning at the semantic level. Notice the threefold use of eimi, “was,” in this verse. Here, a single verb in its three occurrences conveys three different meanings: 1) “In the beginning was the Word,” (in which eimi, “was,” means “to exist”); 2) “and the Word was with God,” (in which eimi followed by the preposition “with” conveys the meaning “to be in a place”); and 3) “and the Word was God,” (in which eimi conveys the meaning “membership in a class: Godhood”).26 Notice also in John 1:1 that logos, “word,” occurs in the predicate position in the first clause, but is in the subject position in the second clause. In the third clause there is again a reversal of the order creating a chiasmus: theos, “God,” is placed before the verb creating emphasis on the deity of the “Word.”27 Lexical meaning is not only inherent in words themselves, but is determined by their relationship to other words in context.

This brings up another important aspect of textual analysis called “pragmatic analysis.” Pragmatic analysis asks the questions “What is the author’s purpose of a text?” and “What does an author desire to accomplish with his text?”28 The text-driven preacher is always attempting to accomplish something with every sermon. All verbal or written communication has at least one of three purposes: 1) to affect the ideas of people, 2) to affect the emotions of people, and 3) to affect the behavior of people. Preaching, like all verbal or written communication, should have all three of these purposes. We should attempt to affect the mind with the truth of Scripture (i.e. doctrine). We should also attempt to affect the emotions of people because emotions are often the gateway to the mind. Finally, we should attempt to affect the behavior of people by moving their will to obey the Word of God.

3. A Practical Example: The Semantic Structure of 1 John 2:15-17. If one were to preach through 1 John paragraph by paragraph, 1 John 2:15-17 constitutes the seventh paragraph in the letter. It contains three sentences in Greek that are usually rendered into English by four sentences. Sentence one contains an imperative (the first one in the letter) and functions semantically as the most dominant information conveyed in the paragraph: “Do not love the world.”

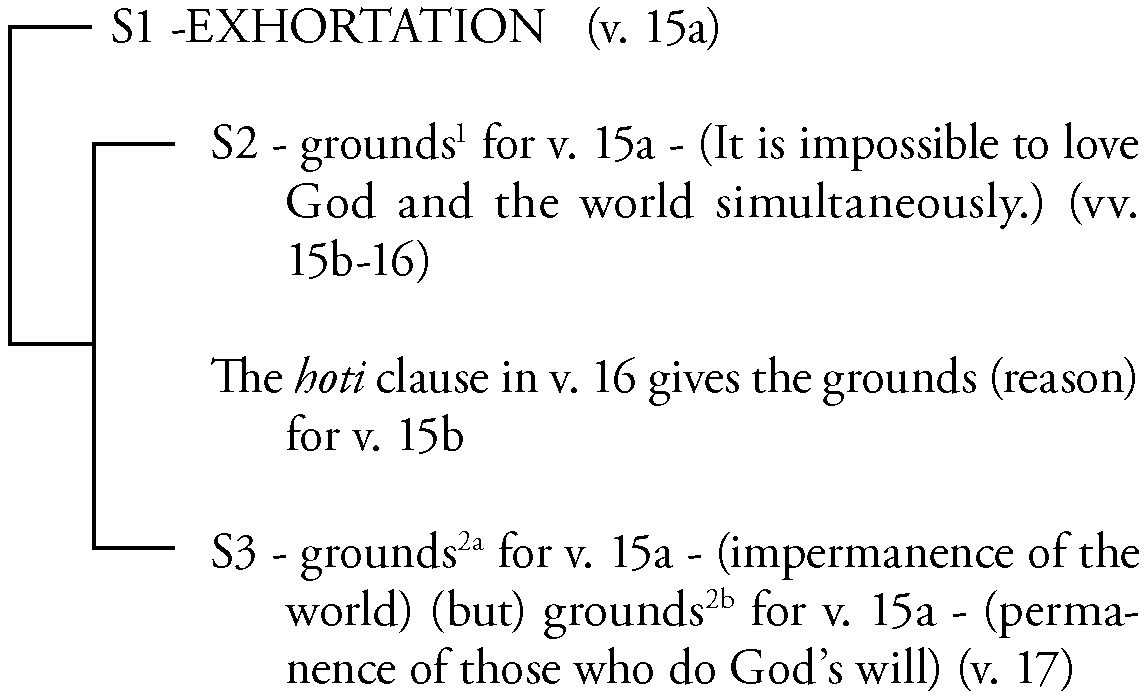

From a semantic standpoint, the structure of 1 John 2:15-17 can be diagrammed this way:

Based on the structure of the text itself, how many main points does 1 John 2:15-17 have? It has one main point, expressed in the imperative in verse 15. How many subpoints does the text have? It has two, each one expressed by the grounds of sentence two and sentence three with sentence three divided into two halves—one negative and one positive—on the basis of the compound structure of the last sentence (v. 17).

From this semantic structure, a text-driven sermon would be outlined or structured accordingly:

I. Don’t love the world … because

A. It is impossible to love God and the world simultaneously

B. The world is impermanent … but the one doing the will of God (that is, being one who does not love the world) is eternally permanent.

Semantically, the text contains one main point and two subpoints. If you preach on this text omitting one or more of these subpoints, then you have not preached the text fully. If you preach this text adding additional main or subpoints beyond these, then you are adding to the meaning of the text. If you make one of the subpoints a main point parallel to v. 15a, then you have mis-preached the text in terms of its focus. If you overemphasize the three parallel prep- ositional phrases in v. 16 and spend most of your time explaining and illustrating them, then you will mis-preach the focus of this text. To omit points, to add points, or to “major” on that which is a “minor” in the text is to fail to preach the text accurately. What you say may be biblical, but it will not be what this text says in the way the text says it.

If we believe in text-driven preaching, then somehow the main and subordinate information which John himself placed in his text must be reflected in the sermon. There may be many creative ways to do this in preaching; however, these elements must be there, or the sermon will be less than truly text-driven.

IV. PREACHING AS FOUNDATIONAL: THE NATURE OF THE CHURCH

A fourth foundation for preaching in the mission of the church is the nature of the church. The nature of the church requires that preaching be paramount in the fulfillment of her mission. The Great Commission as recorded in Mark 16:15 indicates how Jesus viewed preaching as the necessary means for the church to fulfill the Great Commission.

The church was birthed in preaching according to Acts 2. In Acts 6:4, Luke records the Apostles placed a high priority on prayer and preaching as their primary focus: “But we will give ourselves continually to prayer and to the ministry of the word.” Paul says in Romans 10:14 that “faith comes by hearing and hearing by the word of God.” Evangelistic preaching grows the church. Biblical preaching edifies the church. The book of Acts clearly shows this.

In his farewell letter to Timothy, Paul tells him to “preach the Word” (2 Timothy 4:2). You cannot have a church without preaching. You cannot have church growth without preaching. You cannot have church revitalization without preaching. Preaching is fundamental to New Testament ecclesiology. Preaching must be foundational in the mission of the church for theological and pastoral reasons. The church cannot be the church unless she is the preaching church. The classical definitions of pastoral care throughout church history speak of preaching as the primary method of doing pastoral care. For example, Martin Luther said:

If any man would preach let him suppress his own words. Let him make them count in family matters and secular affairs but here in the church he should speak nothing except the Word of the rich Head of the household otherwise it is not the true church… [this] is why a preacher by virtue of this commission and office is administering the household of God and dare say nothing but what God says and commands. And although much talking is done which is outside the Word of God, yet the church is not established by such talk though men were to turn mad in their insistence upon it.

Preaching within the church both equips and challenges the church to fulfill the Great Commission.

V. PREACHING AS FOUNDATIONAL: THE DIVINE MANDATE TO PREACH

The fifth reason why preaching is the foundation of the mission of the church is the divine mandate to preach. The centerpiece and climax of the discourse structure of 2 Timothy is 4:2: “Preach the Word.” This is the only place in Scripture where “Word” (logos) occurs as the direct object of the verb “to preach.” Preaching is God’s method of heralding the gospel to a lost world. Preaching is God’s method of teaching his church doctrinal and ethical truths. We refer to these two aspects as kerygma (heralding the gospel) and didache (teaching). Both words occur in 2 Timothy 4:2–5.

Every time we preach, eternity is at stake. We must realize that, with every sermon, we are not only spiritual surgeons, “rightly dividing the word of truth,” but we are ourselves under the probing knife of the very Word we preach, just as Hebrews 4:12–13 says. Those of us in the pew must hold our pastors accountable to a high standard for preaching God’s Word, all the while remembering that we, too, are being probed by the Word.

The razor-sharp scalpel of the Word penetrates us and becomes a “critic” (kritikos) of our thoughts and intents—including the methods and motives of both preachers and listeners. The author of Hebrews warns in 4:13: “Everything is naked and open before the eyes of him, before whom we must give an account.” Or, to express the Greek wordplay of the author, “He to whom the Word has been given shall one day be required to give a word in return to the One who is himself the Word of God.”

VI. CONCLUSION

I close with J. I. Packer:

The Bible text is the real preacher, and the role of the man in the pulpit or the counseling conversation is simply to let the passages say their piece through him. …For the preacher to reach the point where he no longer hinders and obstructs his text from speaking is harder work than is sometimes realized. However, there can be no disputing that this is the task.29

Since God has spoken in Jesus Christ and in Scripture, there is an answer to our question, a solution to our problem, hope for our future, forgiveness for our sins, and salvation for our soul.

Preach the Word!30

- J. I. Packer, “Introduction, Why Preach?”, The Preacher and Preaching: Reviving the Art in the Twentieth Century (ed. Samuel T. Logan, Jr.; Phillipsburg, NJ: Presbyterian and Reformed, 1986), 4. ↩︎

- Many of the mainline denominations have succumbed to liberalism as evidenced in the writing and preaching of some of their own homileticians. The aptly titled book, What’s the Matter with Preaching Today? edited by Mike Graves (Louisville: Westminster/John Knox, 2004), includes ten chapters by ten homileticians from mainline denominations. The book title is a self-fulfilling prophecy; much of it illustrates what is wrong with preaching today. For example, David Buttrick informs us that the idea that Jesus saves individual human souls is a “Gnostic heresy” and that a gospel of personal salvation is a “heretical gospel” (45–46). Earnest Campbell informs us he believes that while Jesus is the only way for us, he is not necessarily the only way for others. According to Campbell, it is “preposterous” to deny the possibility of salvation to the billions who share this planet with us but do not share our faith (52). ↩︎

- See David L. Allen, “A Tale of Two Roads: Homiletics and Biblical Authority,” JETS 43 (2000): 508–13. ↩︎

- See Stephen Crites, “The Narrative Quality of Experience,” JAAR 39 (1971): 291–311. ↩︎

- Narrative preaching has come under significant critique in recent years, even by those who

were once its ardent supporters. See, for example, Tom Long, “What Happened to Narrative Preaching?” Journal for Preachers 28.2 (2005): 9–14. In 1997, Charles Campbell’s bombshell Preaching Jesus: New Directions for Homiletics in Hans Frei’s Postliberal Theology (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1997), and James Thompson, Preaching Like Paul: Homiletical Wisdom for Today (Louisville/John Knox: Westminster, 2001), both leveled broadsides against the New Homiletic. ↩︎ - See Greg Beale’s The Erosion of Inerrancy in Evangelicalism: Responding to New Challenges to Biblical Authority (Wheaton: Crossway, 2008). ↩︎

- John Stott, Between Two Worlds (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1982), 92. ↩︎

- Haddon Robinson, “Homiletics and Hermeneutics,” in Hermeneutics, Inerrancy, and the Bible

(ed. Earl Radmacher and Robert Preus; Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1984), 803. ↩︎ - James Daane, Preaching with Confidence (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1980), 49. ↩︎

- Haddon Robinson, Biblical Preaching, (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2001), 16. ↩︎

- Lloyd M. Perry and John Strubhar, Evangelistic Preaching, rev. ed. (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2000), 56. ↩︎

- Werner Stenger, Introduction to New Testament Exegesis (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1993), 23. ↩︎

- See 2 Timothy 2:15. ↩︎

- See Steven W. Smith, Recapturing the Voice of God: Shaping Sermons Like Scripture (Nashville:

B&H Academic, 2015), who first used these descriptors several years ago. ↩︎ - From a semantic standpoint, there is a finite set of communication relations that exists for all languages which functions as something of a natural metaphysic of the human mind. See Robert Longacre, The Grammar of Discourse (Topics in Language and Linguistics; New York: Plenum, 1983), xix. These relations are catalogued, explained and illustrated by Longacre and in a more “pastor friendly” way by John Beekman, John Callow and Michael Kopesec, The Semantic

Structure of Written Communication (Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics, 1981), 77–113. ↩︎ - See D. Allen, “Fundamentals of Genre: How Literary Form Affects the Interpretation of Scripture,” in The Art and Craft of Biblical Preaching, 264–67. Scripture employs various genres including narrative, poetry, prophecy and epistles, and good text-driven preaching will reflect this variety as well. There is a broad umbrella of sermon styles and structures that can rightfully be called “text-driven.” For a helpful discussion of this subject, see Dennis Cahill, The Shape of Preaching: Theory and Practice in Sermon Design (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2007). ↩︎

- John A. Broadus, On the Preparation and Delivery of Sermons, (ed. E. C. Dargan; New York: Armstrong, 1903), 118. ↩︎

- Thomas Long, The Witness of Preaching, (2nd ed.; Louisville: WJK, 2005), 5. ↩︎

- Birger Olsson, “A Decade of Text-linguistic Analyses of Biblical Texts at Upsalla,” Studia Theologica 39 (1985), 107, underlined the vital importance of discourse analysis for exegesis when he noted: “A text-linguistic analysis is a basic component of all exegesis. A main task, or the main task of all Biblical scholarship has always been to interpret individual texts or passages of the Bible. … To the words and to the sentences a textual exegesis now adds texts. The text is seen as the primary object of inquiry. To handle texts is as basic for our discipline as to handle words and sentences. Therefore, text-linguistic analyses belong to the fundamental part of Biblical scholarship.” See also the excellent chapter by George Guthrie, “Discourse Analysis,” in Interpreting the New Testament: Essays on Methods and Issues (eds. D. A. Black and David S. Dockery; Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 2001), 253–71. ↩︎

- Among the more recent resources that aid the preacher in exegesis, see Douglas Mangum and Josh Westbury, eds., Linguistics and Biblical Exegesis (Lexham Methods Series; Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2017). For those who use computer software programs in their exegesis of Scripture, see Mark L. Strauss, The Biblical Greek Companion for Bible Software Users (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2016). Consult also Steven E. Runge, Discourse Grammar of the Greek New Testament: A Practical Introduction for Teaching and Exegesis (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2010). ↩︎

- Longacre, Grammar of Discourse, 3. See also Beekman, Callow and Kopesec, The Semantic Structure of Written Communication, 35–40. ↩︎

- Beekman, Callow and Kopesec, The Semantic Structure of Written Communication, 8–13. See also Constantine R. Campbell, Advances in the Study of Greek: New Insights for Reading the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2015). ↩︎

- Timothy Friberg and Barbara Friberg, The Analytical Greek New Testament (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1981), 834. ↩︎

- A helpful work here is Constantine R. Campbell, Basics of Verbal Aspect in Biblical Greek (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2008). ↩︎

- If a New Testament text has a string of verbs in the aorist tense, and then suddenly a perfect verb pops up, there usually is significance to this tense shift. See, for example, Romans 6:1-5 where this very point is illustrated by the use of the perfect tense translated “have been united” in v. 5. In the Abraham and Isaac narrative of Genesis 22, at the climax of the story, there is a sudden onslaught of verbs placed one after another in staccato fashion in the Hebrew text in Genesis 22:9-10. This has the effect of heightening the emotional tone of the story and causes the reader/ listener to sit on the edge of his seat as it were, waiting to find out what happens. In the exegetical process, one should pay close attention to verbals (participles and infinitives) as well, as these often play crucial modification roles. ↩︎

- See Jan Waard and Eugene Nida, From One Language to Another: Functional Equivalence in Bible Translating (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1986), 72. ↩︎

- Waard and Nida, From One Language to Another, 72. ↩︎

- A. Kuruvilla has reminded us of the importance of this aspect of text analysis for preaching in his Privilege the Text! A Theological Hermeneutic for Preaching (Chicago: Moody, 2013). ↩︎

- Packer, “Introduction, Why Preach?,” 17-18. ↩︎

- Much of the material in this article has been adopted from my chpater in Text-Driven Preaching (ed. Daniel Akin, David L. Allen, and Ned L. Mathews; Nashville: B&H, 2010). ↩︎