World Christianity

Southwestern Journal of Theology

Volume 61, No. 2 – Spring 2019

Managing Editor: W. Madison Grace II

Note1

The missions’ enterprise of the Nigerian Baptist Convention (NBC) has faced the rise of Islamic insurgency over the years. The continued missionary activities of the NBC have, therefore, been affected in various ways. While it could be affirmed that the effect has both opportunities and challenges, the challenges are becoming so overwhelming that the opportunities are becoming bleak.

This article establishes the impact of Islam and call for Islamization, through religiopolitical violence, on the glocalization of the Church and the retransmission of the gospel in Nigeria. While religious and political violence predates colonization in the region and informs the situation today, the focus will be upon the development in Nigeria between 1980 and 2020. This period provides two major historical paradigms that inform the context for the changes attending the Church’s self-image, commitment to gospel retransmission, and the glocal impact. The two paradigms, in turn, serve as a springboard into the future of Christianity in Nigeria and beyond.

Historical Survey of Insurgency: 1980–2018

The first season of the impact of religious violence on the Church in Nigeria was between 1980 and 2000 with a series of attacks occurred. Muslims were seeking to satisfy requirements for an Islamic state for Nigeria, which was the end of a long process. Prior to this they were able to enshrine the sharia into the Nigerian Constitution in 1979.2

Opposed to a secular state, which was considered to be Western and therefore inappropriate, they had hoped that sharia would serve as the sole law guiding the nation. Muslims fought for Nigeria to join the Organization of Islamic Countries (OIC) to which the Nigerian delegation was prevued at its beginning in 1969.3 Other requirements for membership beyond operating sharia included payment of membership fees, reduction or eradication of Christianity from the land, ensuring all leadership positions are occupied by Muslims, non-Muslim rights withheld, etc. These have proved difficult to achieve.

Several factors illustrate these difficulties such as dissension by some Muslims from the pursuit of Islamization. These Muslim dissenters were considered infidels and non-Muslims and were targets of violence in the desire to purify Islam. The Christians in Northern Nigeria also endured deprivation and denial of rights.4

Between 1980 and 1999 the second republic rose militarily with a Muslim presidency, thus satisfying an aspect of the requirement of OIC members.5 Prior to the military intervention a religious bill was being considered that would outlaw public preaching;6 it was targeted at the Church. The intervention of the military in the mid 1980s, which happened to be Muslim, facilitated executive fiats of membership to the OIC7 leaving one final and difficult requirement: a ten-year consecutive annual membership fee payment.

From AD 2000 to the present this same pursuit continued and became intensified. The rise of a presidency from the Southern Christian extraction in 1999 brought a renewed effort to Islamization. Twelve of nineteen states of Northern Nigeria declared themselves as sharia states.8 It marked the beginning of a concerted effort to achieving their purposes by applying pressure on the sitting government. Some success was gained during Olusegun Obasanjo’s and Ebele Goodluck Jonathan’s presidencies with a few payments to the OIC being made. Also, during Jonathan’s rule Almajiri schools were built and partnerships with Islamic countries were secured, which led to Islamic banking and loans coming to Nigeria.

In the year AD 2000 several churches were destroyed, especially in Kaduna. The Baptist Theological Seminary was also burnt down. Though this destroyed lives and property, Christianity was not eradicated. Boko Haram came to power after the demise of Musa Yar’Addua and his deputy, a Christian, took his place in 2010. Since then the rate of hostage taking, killings, maiming, and destruction of properties has intensified.9 The current government was ushered in with the promise to solve the problem of the insurgency in 2015, but instead of peace only violence has increased. While no record of OIC membership payments, the government has strengthened Islamic banking and has acquired a sukkuk loan for development. Appointed offices of the Federation were all replaced with Muslim leadership—from security, paramilitary and military, and even in the judiciary. All efforts have been made to ensure the election of Muslims into elected offices.

The Muslim constituencies in the nation do not view this as discrimination. To them, anything less than operating under Islamic law is unacceptable. They see it as seeking equality with the Christians who had enjoyed the secular law which is Christo-western.10 Below is a brief overview of the suffering of the Nigerian Church.

Boko Haram and Its Impact on Nigerian Baptists

The insurgency of Boko Haram (BH) affected Nigerian Baptists in many ways. This section will discuss the impact of the insurgency, the Church’s image, the Church’s response, the transformation of life, gospel retransmission, and, finally, its glocalization.

The Physical Impact of The Insurgency on Nigerian Baptists

The Nigerian Baptist churches have suffered in various ways in the hands of BH. The physical hardships inflicted on Nigeria have led to the destruction of churches, the killing of Christians, and displacement of many people, especially those living in the northeast. Interviews conducted report on various aspects of the suffering of the Baptist churches starting with the challenge of displacement.11 Many Christians abandoned their homes, businesses, and farms due to the attacks. Most of these who were displaced left with the hope to return soon, but ended up having to seek help at refugee camps. They are affected spiritually, physically, psychologically, and economically.12 The displacement “has caused untold hardships on both children and adults in Nigeria.”13

S. Ademola Ishola notes that the indigenous northern Christians have suffered the most. They have no place to go compared to Christians from the south who live in northern Nigeria. These southerners have the option of relocating to their states of origin, which is outside the region affected by the BH insurgency. The challenge facing Christians of northern origin includes the need to re-establish their homes and means of livelihood once the insurgency ends.14

Northern Christians face challenges from Muslims but also from Christians from other parts of the country. They do not readily receive support from their fellow Christians,15 and are even not welcome in some Christian fellowships. This discrimination against northern Christians by Christians from other parts of the country is not easily reported.16 The results of the insurgency compounded the challenges for crop farmers and herdsmen by bringing famine.17 Christian businesses were also destroyed and individuals were maimed or killed.18 These communities used to have several social events that brought it together that cut across religious, ethnic, and regional lines. Since the rise of BH, however, these events are no longer possible because of suspicion, hatred, and fear of volatility arising from such occasions. The memories of the destruction of churches, killings, and displacement caused by a group claiming religious allegiance has weakened opportunities for gospel retransmission.19

Those most affected in the northeastern states of Nigeria were over 200 local Baptist churches and 138 pastors in Adamawa and Bornu. Only two church buildings were still standing at the time of the interview.20 Of 138 pastors in the Conference, only about 10 of them are in the Maiduguri metropolis. The members of all others have either been killed or displaced to other states.21 Those who escaped and dared to return were killed as well. Evangelism came to a standstill. Most churches that still met were simply providing solace for the survivors. Many have resolved not to return to the region because of fear, a threat to life, and being a minority by religions and ethnic affiliation.22

Boko Haram and Image of Nigerian Baptists

A critical observation reveals that Baptist churches in Nigeria basically see themselves as socio-political groups that will fight for their rights. Using socio-political apparatuses, the churches operate as pure social entities in worship. Worship is often entertainment driven and inclined towards marketing.23 The churches also seek to field political offices with members who will be pre-disposed to defending the course of the church. There is a strong drive towards providing political leadership at local, state, and federal levels. The arguments have been, “Christians shying away from political involvement will result in the rule of the ungodly.” The desire for political representation is higher than the desire for missionary engagement.24

The churches are pietistic and seek personal spiritual satisfaction with little concern about non-Christians. Christian commitment is primarily judged by participation in religious (church) activities rather than a transformed life and commitment to the great commission. Spirituality is measured by commitment to prayer activities and philanthropism. The moral impact on society is secondary to the manifestation of the miraculous.25 In short, what one gets from God is more important than seeking to know and obey God’s expectations.

The churches look to government to bring about change in society. They look to the political-legal system to defend religious liberty. They hope for a peaceful community enacted by the political will of national leaders. The preservation of the church seems to be dependent on political power and control, which has motivated many to be politically involved.

Theologically, the churches are not conscious that they are pilgrims on the earth. They see the world and its material gains as a Christian’s right. The churches place their hope in using the “power of being children of God” to defend the church. They believe that if Christians are spiritual then no challenges will come their way. They will pray, command every situation, and all they ask will come to pass. Any suffering is a consequence of individual sin.26 The growth and expansion of God’s kingdom is here in the world. Most of the churches look forward to time here on earth when Christians will be the majority and things will be done the “Christian way.” Thus, there is not much commitment to missions.

The insurgency also brought religious, ethnic, and regional divides both within and outside the church.27 Ethno-linguistic divides and sentiments are expressed in establishing churches, appointing leaders, or even calling pastors to already existing churches. The desire among many to have a church with their isolated cultural identity within pluralistic contexts is a growing phenomenon. Ethnic affinity determines suitability for a given responsibility in the churches rather than God’s leading.28

The Baptists are gradually becoming prosperity driven. The health and wealth gospel is influencing many in their consideration of missions and persecution.29 The expected transformation that will produce the fruit of the Spirit and appropriate self-image is lacking. This also, in turn, affects the retransmission of the gospel.30 Similarly, Zacharia Ako noted that this is the most difficult time in Nigeria regarding the Christian-Muslim relations. Instead of the Church drawing closer to God, the church is getting further away from God. “Persistent attack from the Muslims or BH insurgency” is breathing hatred and encouraging violent responses.31 The BH insurgency is a clarion call for the church to awaken to her responsibility—missions in the face of persecution32 as well as a need to evaluate her theology.

The Church’s Response

Earlier Christian responses (prior to 2000) to religious crises in Nigeria were better than the response today. These crises were understood as persecution, but the Church remained involved in evangelism and Christians apparently lived more exemplary lives.

In those days, in the early 70’s, late 60’s, there were mini-revivals in Nigeria, especially among the youths on campuses. There was hardly any church that I knew of, that did not have a day of evangelism. Three programs were prevalent … bible study … prayer meetings and evangelism.33

It was also noted that Muslim opposition was accepted as an inevitable challenge, which led the churches to continue to evangelize and interact with Muslims.34 Interviews conducted also affirmed this change. During the periods of between 1980 and 2000, Muslims and Christians protected and cared for each other. Here is an experience in Kaduna in 1987:

Certainly, I remember vividly when we had a large-scale religious crisis in 1987 particularly in Kaduna State. Christians then didn’t retaliate. Most of the crisis that erupted, led to the burning down of many churches. But interestingly, the following Sunday after the crisis, believers were seen worshiping on the rubbles of those … churches that were burnt. And, surprisingly, the attendance that particular Sunday in most churches was fuller than usual. … But subsequently, over the years when Christians began to feel the need to retaliate and when that started happening, then it developed a circle of violence that has not been … broken up till this moment.35

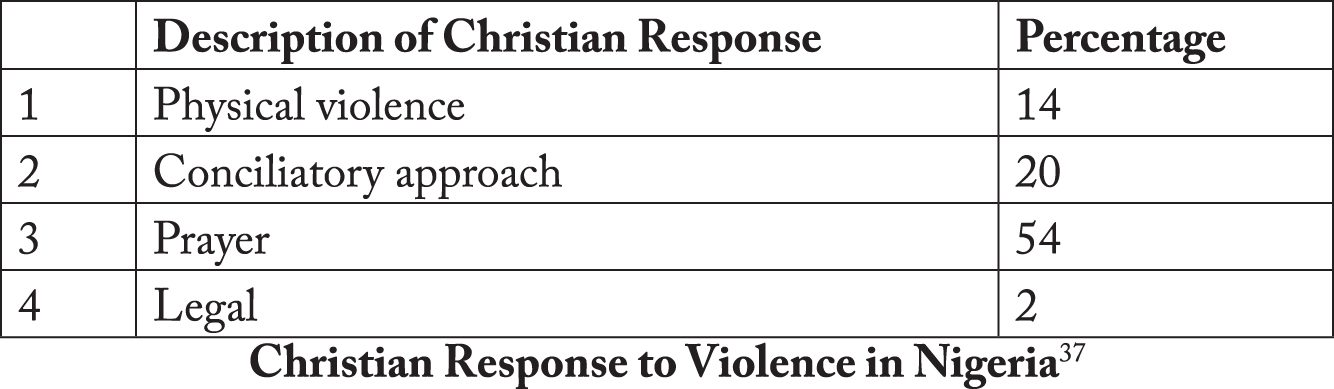

In 2004 John Ade Ajayi noted the growing Islamic violence in Nigeria and warned of the danger for Nigerian Christianity and compared it to similar situations in Egypt. He noted four basic responses of the Nigerian Church at the time to the violence.36

Note37

Ajayi noted that tendency towards violence was growing in Nigeria since 2004.38 There are indications that these statistics have further changed significantly.

Since 2006, Muslims welcomed Christians who were fleeing the insurgency only to hand them over to fellow Muslims. By 2009 previous Christian-Muslim relationships were gone and Christians began growing in violent responses towards Islamic opposition.39 This change of attitude did not go unnoticed even by the Muslims who felt Christians changed from who they used to be.40

Attitudinal change has itself constituted a barrier for reaching Muslims today. One finds an expression of hatred towards Muslims. The trust that once existed has given way to resentment.41 Transformation expected from faith in Christ does not seem to have taken place in the lives of significant numbers of people in the Church today. It is observed that there is a deficiency in evangelization, which is central to the experience of transformation. Most churches no longer have a specified time for evangelism. Regarding trust, Joseph J. Hayab noted, religion and ethnic affinity have become a far higher basis for appointments and support of the masses rather than competence in religious and political spheres in Nigeria.42

Muslims and Islam are seen as the enemy of the church.43 In reaction to this trend S. Ademola Ishola says:

You find (some) among us who feel it must be fire for fire this time around and Christian … (passivism) is no longer tolerated. That we should fold our arms and let them continue to kill our people … For me personally of course, as a denominational leader, I feel boxed – do I command people go ahead and also kill them; destroy their Mosque or properties?44

The statement above indicates that leaders are faced with a dilemma. While a number of Christian leaders know that violence is not appropriate, they are sympathetic, or even willing, to assent to such action. They are in between what they know is right and what they want to see happen.

For Ajayi, the rise of BH is not unconnected to the failure of the Church in serving society. The self-image of the Nigerian Church has dimmed the light of the gospel. While most Nigerian Christians do not see the necessity of evangelizing Muslims, the Muslims also do not see Christian godliness any longer and, thus, are not attracted to the Christian message. Muslims see indecent dress,45 eating of unholy foods,46 insincerity,47 alcoholism,48 exploitation, corruption,49 and sexual morality as prevalent among cultures identified with Christianity in northern Nigeria.50

The situation was compounded by the failure of the church in evangelism, missions, and discipleship which is replaced today with “prosperity; … health and wealth Christianity and actually hero worship.”51 When evangelization does occur it is material centered, business-like, and miracle-centered. Amusa Iyanda Lawuyi noted that one of the factors that gave rise to Islam in Nigeria is nominalism,52 a perspective prevalent on the whole Nigerian society. Missions is redefined as “welfarism” and social service within the church. The spiritual well-being of members no longer occupies a central place in worship. Members are impressed to pray against their enemies rather than “rescue the perishing and disciple them.”53

Attitudinal changes informed by fear, anger, aggression, distrust, hatred have become prominent bringing about a growing tendency for retaliation.54 Spirituality is seen as a personal matter not concerned with fellowship with others. As a result, even church worship is pietistic and selfish merely satisfied with preserving the status quo.55

The Church is responding in many worldly ways. Hayab noted three major responses—situational ethics, self-defense, and an affront against an identified enemy.56 Other responses identified are a misinterpretation of the Bible, violent prayers,57 and commitment to appeasing the masses.

The worldly ways the Church is responding to BH reveals its spiritual state. Some are even returning to African Religion. Babagunda and Hayab state that the insurgency is making “so many Christians go back into African Traditional Religion (ATR) seeking powers so that they could have … immediate protection so to say from those people that take advantage of killing the Christians anyhow.”58 Many in the churches have the impression that they are vulnerable and could secure protection through their old religions; revealing the inadequacy in transformation.59 Domestication of the faith and the return to ATR, a development even Muslims disdain,60 also have taken away the transforming power of the gospel.61 In effect, the Bible is simply added to the existing religion, making Christianity utilitarian and self-centered.

With these challenges there have been some who have researched various approaches to ministry among Muslims, but most of the work is unnoticed and remain only in theological institution libraries.62 There are also publications that provide a biblical response to violence on the Church in Nigeria as a product of academic conferences.63 Pertaining to missions, there is an unwritten policy that a missionary should be indigenous, but this has negatively affected missions because, for the unreached, unengaged groups, there is virtually no one to send and many new believer are given ministerial responsibilities.

The Impact of Insurgency on Gospel Retransmission

Boko Haram has affected gospel retransmission. In contrast to the the 1980s, there is an observable decline in missionary commitment especially to the Muslims and the cultural groups that are predominantly Muslim.64 The relocation of Christians and Muslims has increased the barrier between them. The manner of relocation also made evangelism and mission more challenging. Baptist churches no longer share the gospel, especially with Muslims, compared to the past. Pastors seek to serve outside the northern region of the country, which has also led to a decline in Church membership. A significant percentage of worshipers no longer go to church for worship and engage in evangelism. This inability to gather for worship has further weakened the possibility of doing missions.65 This challenge of accomplishing missions is further complicated by a desire of Christians for justice and vengeance.

Retransmission of the gospel is replaced with a prayer against the Islamic agenda, which is a noticeable change from historic responses to persecution in the Church. While most pastors and non-pastors do not see the need to reach out to Muslims, some of the pastors in the middle of the insurgency are calling on the church to engage the Muslim communities with the gospel more than the pastors outside of it.66 For James Vandiwghya, BH created fear and suspicion in the hearts of those who would desire evangelism. It became difficult to evangelize even the non-Muslims because of BH’s methods.67

It has changed the mood and ministry approaches of the Church from large evangelistic rallies to a total withdrawal from outreach.68 The decline in ministry and worship participation is due to relocation to areas considered more peaceful.69 Prior to the advent of BH, churches organized evangelistic rallies, but this method had to be suspended because BH targeted these gatherings. The existing tension also caused open preaching to cease.

The Glocal Impact of the Nigerian Baptists

The Boko Haram insurgency directly affects the entire nation of Nigeria. However, this research concerns its impact on Nigerian Baptist Convention churches which serves as a case study for the impact on the church in Nigeria.

The Local Nigerian Baptists. There are two aspect to Nigerian Baptists’ impact at home—within and outside the denomination. But more attention will be given to the impact within. The Nigerian Baptist Convention as a denomination has demonstrated great intentionality and commitment to missionary work in northern Nigeria despite limited resources for such ministry. It is among the last few denominations formally to enter northern Nigeria for the purpose of missions. While regional allocation among mission agencies in Nigeria in the nineteenth century is partly the reason for the delayed entry, NBC’s self-established churches have been in northern Nigeria for over a century. Most of these churches were primarily established by lay Yoruba traders for themselves.70

Though not proactive towards reaching the northern indigenous peoples,71 they made some significant impact on what is known today as Baptist work in northern Nigeria.72 Today, the NBC has thirteen (13) conferences out of thirty (30)73 and ten (10) home mission fields74 in northern Nigeria. Four (4) of its eleven (11) theological schools are also in the North. But much has changed since the advent of BH. Previous insurgencies and religiously (Islamic) motivated violence did not devastated the Nigerian Baptists as has BH. Below are some observable changes to the denomination at home.

Churches made of northern indigenous peoples are most affected and feel most abandoned.75 The Nigerian Baptists at local and national levels are not responding effectively to the emotional, physical, material and spiritual needs of the victims. The 2012 shift of the Convention’s venue from Abuja on the advice to not to take the Convention to a war zone was disheartening and discouraging to the churches in the North who also saw no drastic steps taken to stand with those affected by the insurgency. The BH crisis has further divided the church, which was already suffering from ethnic tension.76 This development strengthened the ethnolinguistic, geopolitical, and religious tensions in the convention.77

The crisis has further weakened missions to Muslims in the North. The local church missions in the North, which is primarily focused on the diaspora is dying due to the relocation of target groups. The effort towards the indigenous peoples is also closing due to the relocation of the Christian population and decline in interest. BH has further strained the fragile interethnic relationships with peoples of Islamic background and closed the door to missionary opportunities with them while many mission agencies and denominations are focused on ATR background peoples in northern Nigeria.78 Another way by which mission doors are closing is the changed attitudes among Christians towards Muslims in general, which has aided the accusations of insurgents that Christianity is abominable.

The denominational missionary efforts are also greatly affected. None of the fields targeting indigenous Muslim peoples in the North under the GMB have a missionary and there are no recruitments while the few serving missionaries are discouraged.79

Interdenominationally, the NBC is one of the leading evangelical missionary churches and has the oldest indigenous missions’ board.80 It has contributed in various ways and inspired other mission agencies in Nigeria.81 Its growth impressed all its partners and observers. It has initiated several pioneer missions to unreached, diaspora, and other specialized ministries.82 It is also a member of the Nigerian Evangelical Missions Association (NEMA) and Joint Christian Ministry in West Africa ( JCMWA)—a partnership for the purpose of missions. The NBC is one of the largest evangelical bodies and has an influence on several other denominations within the continent.83

Nigerian Baptists Impacting World Christianity. Samson Ayokunle, the President of the NBC bemoans the neglect of the international Christian community over Nigeria’s fight against BH. His call for assistance was primarily a call to material and human rights support for the Church in Nigeria.84 His expression is indicative of the frustration regarding the best way to respond to the crisis. The desire for justice alongside the growing humanitarian need had seemingly removed the sympathy for the spiritual state of the perpetrators of this violence.

The GMB is involved in missions to Muslim countries in Africa—Chad, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Guinea. What is happening at home will surely affect what happens in those places as well.85 Safety considerations inform the appointments of missionaries. Oluwafemi Adewumi, serving in Mali, expressed the reservation of sending missionaries. He noted, when missionaries are appointed, they face a challenge from those who will persuade them not to go to volatile Muslim areas.86 Several agencies have had to recall their missionaries from places considered as unsafe. In some instances, the indigenous people advise missionaries on safety issues as well.87

From World Christian Studies (WCS) writings also, Nigeria is one of the countries in the southern continent identified as a hub of Christianity. Discussing the place of Nigeria and the Islamic tension Jenkin notes,

The twin experience of Sudan and Egypt explains why African Christians, so uncomfortably close to the scene of action, should be nervous about any extension of Islamic law and political culture. If Muslims insist that their faith demands the establishment of Islamic states, regardless of the existence of religious minorities, then violence is assuredly going to occur. This issue becomes acute in the very important nation of Nigeria which is today about equally divided between Christians and Muslims.88

Furthermore, he noted,

When in 2000 the U.S. intelligence community sketched the major security threats over the next fifteen years, the explosion of religious and ethnic tensions in Nigeria was prominently listed. Depending on international alignments, the religious fate of Nigeria could be a political fact of immense importance in the new century.89

The above is indicative that Nigeria and its developments are being watched globally. Nigeria’s political, economic, and religious developments will provide one form of influence or another, which raises the need for global Christianity to respond.

The Future of World Christianity, 2018 and Beyond

The insurgency has revealed the true state of the Church in Nigeria. The Church is fast losing its glocal character and the power of gospel retransmission. It is becoming nominal and reveals its weakness to confront persecution adequately. The Church is also losing vitality due to the decline in its theology, especially its teaching of the Bible.

Two opposing directions are possible in Nigeria. If the trend towards more violence, a loss of the Church’s image, ineffective glocalization, and the use of worldly responses, then the future of world Christianity is bleak. However, the opposing direction will result in a formidable worldwide faith. When Nigerian Baptists return to teaching and upholding the Bible, a commitment to missions and discipleship, it will build an army that will bring about transformation and growth of the Nigerian Church. This, in turn, will restore the mission and missionary commitments and bring a bright future to the Church.

- This article is an excerpt from my dissertation titled “World Christianity in Crisis: Glocalization, Re-transmission, and Boko Haram’s Challenge to Nigerian Baptists (2000–2012)” (PhD diss., Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, 2016). ↩︎

- Matthew Hassan Kukah, Religion, Politics and Power in Northern Nigeria, (Ibadan: Spectrum, 1999), 115–44. ↩︎

- Jan H. Boer, Christians: Why We Reject Muslim Law, Studies in Christian-Muslim Relations, vol. 7 (Belleville, Ontario: Essence, 2008). See also, Joseph Kenny, “Sharia and Christianity in Nigeria: Islam and a ‘Secular’ State,” Journal of Religion in Africa 26, no. 4 (November 1996): 360–62, http://www.jstor.com/stable/1581837; “Flashback: The Major Players in Nigeria’s OIC Membership,” Nairaland, 2 January 2015, http://tinyurl.com/zkamjtf. ↩︎

- Jan H. Boer, Nigeria’s Decades of Blood. Studies in Christian Muslim Relations, vol. 1 ( Jos: Stream Christian, 2003), 38ff. Zach Warner, “The Sad Rise of Boko Haram,” New Africa (April 2012): 38–39. Kukah, Religion, Politics and Power in Northern Nigeria, 154–56. ↩︎

- “Flashback,” 14, Danjuma Byang, Citing Kabiru Yusuf “Nigeria in OIC.” See also, Bede E. Inekwere, “A History of Religious Violence in Nigeria: Grounds for a Mutual Coexistence between Christians and Muslims” (PhD diss., University of the West, 2015). ↩︎

- Audi, “World Christianity in Crisis,” 334–38. ↩︎

- “Flashback.” ↩︎

- John Oluwafemi Adewumi, “Towards Developing a New Approach to Evangelism in Northern Nigeria” (unpublished essay, The Nigerian Baptist Theological Seminary, 2006), 1. ↩︎

- Daniel Egiegba Agbiboa, “Why Boko Haram Exists: The Relative Deprivation Perspective,” African Conflict & Peacebuilding Review 3, no. 1 (Spring 2013): 1, http://tinyurl.com/npl2d4d. ↩︎

- Jan H. Boer, Muslims: Why the Violence? Studies in Christian Muslim Relations, vol. 2 (Belleville, Ontario: Essence Publishing, 2004), 65, citing, New Nigerian. See Kenny, “Sharia and Christianity in Nigeria,” 357–61. ↩︎

- Information about those interviewed is found in, Audi, “World Christianity in

Crisis,” Appendix 2, 207–08. Nine people were interviewed. (Additional information about each of them is found in the pages containing interview transcripts in the appendixes as follows: Rev. Zacharia Joshua Ako: 210, 217; Rev. Dr. S. Ademola Ishola: 219; Rev. James Vandiwghya: 228; Rev. Saul Anana Danzaria: 235; Rev. Joseph J. Hayab: 246–49; Rev. Thimnu Babagunda: 266; Rev. Prof. John Ade Ajayi: 278–82; Rev. Dr. Oluwafemi Adewumi: 291–92; and, Rev. Dr. Joseph Audu Reni: 299–300). ↩︎ - James Vandiwghya, Interview Transcript, 20 December 2014, 229. ↩︎

- Zacharia Joshua Ako, Interview Transcript, 23 November 2014, 211. ↩︎

- S. Ademola Ishola, Interview Transcript, 23 December 2014, 220–21. ↩︎

- Moses Audi, “The Challenge of Ethno-Linguistic Crisis to Missions Effort in Nigeria,” Missiologue 1 no. 2 (November 2011): 5–6. ↩︎

- Names of persons left out intentionally for reason of security. The pastor who was a victim of this experience shared this with a small group during a Joint Christin Ministry in West Africa ( JCMWA) meeting in Jos, Nigeria on 26 September 2013, at Ekklisiyar Yan’uwa a Nigeria (EYN—Church of the Brethren) Headquarters, Jos. ↩︎

- Vandiwghya, Transcript, 20 December 2014, 229. ↩︎

- Saul Anana Danzaria, Interview Transcript, 20 December 2014, 236. ↩︎

- Vandiwghya, Transcript. ↩︎

- Danzaria, 236–37. Vandiwghya, Transcript. ↩︎

- Danzaria, 236–38, 243–44. S.A. Danzaria, “The Christian Response to Religious Persecution 1 Peter 4:12–19,” Golden Gate Baptist Church: Annual Session of Fellowship Baptist Conference, 21–23 February 2013, 9–11.John Ade Ajayi, Transcript, 283, 285. ↩︎

- Enima Thimnu Babagunda, Interview Transcript, 27 May 2015, 268–69. ↩︎

- Danzaria, Transcript, 243; Ajayi Transcript, 280, 286. ↩︎

- Ground for this assertion is the discussion on the response of the church above. See also, Kukah, Religion, Politics and Power in Northern Nigeria, 7–8; Matthew Hassan Kukah, Democracy and Civil Society in Nigeria (Ibadan: Spectrum, 1999), 97–102. ↩︎

- Ajayi, Transcript, 280; John J. Hayab, Transcript, 254; J. Audu. Reni, Transcript, 303; Babagunda, Transcript, 270. ↩︎

- Audi, The Church as a Pilgrim Community (Kaduna: Soltel, 2015), 21–51. ↩︎

- Online reaction to the arrest of herdsmen with weapons reveals such sentiment. See “Soldiers Arrest 92 Armed Herdsmen in Abuja,” Punch, http://www.punchng.com/soldiers-arrest-92-armed-herdsmen-in-abuja/. ↩︎

- Moses Audi, An Evaluation of the Homogeneous Presupposition in African Mission (Ibadan: O’dua, 2003), 14–29. See Hayab, Transcript, 255–56. ↩︎

- Ajayi, Transcript, 280–81. ↩︎

- See Hayab, Transcript, 255–56. ↩︎

- Ako, Transcript, 216. ↩︎

- Ako, 215–17. ↩︎

- Ajayi, Transcript, 17 July 2015, 280. ↩︎

- Ezekiel A. Bamigboye, History of Baptist Work in Northern Nigeria 1901 to 1975 (Ibadan: Powerhouse, 2000), 56–57. ↩︎

- Reni, Transcript, 24 January 2016, 301–02. ↩︎

- John Ade Ajayi, “Missiological Implications on the North African Christianity for the Nigerian Christians,” (MDiv Thesis, The Nigerian Baptist Theological Seminary Ogbomoso, 2004), 63. ↩︎

- Ajayi. “Missiological Implications,” Tabulated by Moses Audi. It is unclear if the responses provided reflect an overlap from the instrument Ajayi used in data collection, such as the possibility of such a tendency was high, see Ajayi, “Missiological Implications,” 102–04. ↩︎

- Ajayi, “Missiological Implications.” ↩︎

- Vandiwghya, Transcript, 230–31. ↩︎

- Vandiwghya, Transcript, 305; Ako, Transcript, 213, 215; Hayab, Transcript, 257. ↩︎

- This is acknowledged by most of the interviews conducted. See Audi, “World Christianity in Crisis,” Appendix B. ↩︎

- Hayab, Transcript, 248. ↩︎

- Danzaria, Transcript, 238; Ishola, Transcript, 220; Ako, Transcript, 213–14; Hayab, Transcript, 255. ↩︎

- Ishola, Transcript. All those interviewed noted the growing tendency to the violent response to insurgency and toward Muslims in general. See Ako, Transcript, 212. ↩︎

- See, Eunice Adewumi, “The Effect of Islam on Women on Evangelizing Women in Northern Nigeria,” (Essay, Nigerian Baptist Theological Seminary Ogbomoso, 2004), 43; Kukah, Religion, Politics and Power in Northern Nigeria, xi, 39. ↩︎

- Foods considered unholy such as pork, dog meat, cat meat, etc. are associated with those affiliated with Christianity. ↩︎

- In the business world, those who will doubt the cost of commodities from Muslims after asking for the true cost are church affiliates. This makes the Muslims feel they are not sincere since they cannot trust the true cost as demanded. ↩︎

- Simon Heap, “We Think Prohibition Was a Farce: Drinking in the Alcohol Prohibited Zone of Colonial Northern Nigeria,” International Journal of African Historical Studies 31, no. 1 (1998): 23-51, http://www.jstor.org/stable/220883. There are local establishments for drinking alcoholic substances all over the Christian dominated areas of the North. Churches and drinking establishments are side by side. Dowry requirements include alcohol. ↩︎

- When a contract is given to a Muslim, you are likely to get a better bargain than giving it to one affiliated to a Christian. ↩︎

- Most hotel ownership and involvement in prostitution are associated with church people by the Muslims probably by virtue of their names and dressing. It is the reason that part of the targets for the insurgents are drinking establishments. See Heap, “We Think Prohibition Was a Farce.” Muslims may fear the application of Sharia. The Muslim practice of purdah also keeps the women in homes. See Adewumi, “The Effect of Islam on Women on Evangelizing Women in Northern Nigeria.” ↩︎

- Ajayi, Transcript, 280. Ajayi further noted that while Nigerian Pentecostals have borrowed from American televangelists, all other churches, including the Baptists, are adopting such teachings, 284. ↩︎

- Amusa Iyanda Lawuyi, “The Challenges Towards Evangelizing the Hausa Speaking Muslims in Agege Area of Lagos State,” (Essay, Nigerian Baptist Theological Seminary Ogbomoso, 2004), 62. ↩︎

- Ajayi, Transcript, 280. ↩︎

- Reni, Transcript, 301. ↩︎

- The Churches are inward looking. See Danzaria, Transcript. ↩︎

- Hayab, Transcript, 255. ↩︎

- Some examples of violent prayers are also called “warfare prayers” and are reflected in the devotional guide used by the Baptist family. Daily Encounter with God 2015. Ibadan: Sunday School Division, Christian Education Department, NBC, 2015, ( January 1, 11, 18, and 20, 2015). ↩︎

- Babagunda, Transcript, 269; Hayab, Transcript, 251. ↩︎

- Babagunda and Hayab, Transcript, 269. ↩︎

- They disdain AR and equate it with Christianity because they see the practices among groups that claim to be Christian. It is one of the reasons the Muslims see Christianity as western civilization. See Jibrin Ibrahim, “Religion and Political Turbulence in Nigeria,” The Journal of Modern African Studies 29 no. (1991): 115–21, http://www.jstor.org/stable/160995. ↩︎

- Babagunda, Transcript, 269–70, 272. Hayab, Transcript, 251. ↩︎

- Abiodun Sunday Bonibaiyede-David, “Church Planting Strategies in Closed-Door Countries: A Necessity for NBC Missions,” (M. Div. Essay, Nigerian Baptist Theological Seminary, 2002), 39-49b. Audi, “Evangelism among the Fulbe in Nigeria,” 27-31. Adewumi, “The Effects of Islam on Evangelizing Women in Northern Nigeria.” Adewumi. “Towards Developing a New Approach to Evangelism in Northern Nigeria.” ↩︎

- Moses Audi, “Biblical Response to Global Violence” BTSK Insight 15, May 2018. ↩︎

- Reni, Transcript, 303, 306; Ako, Transcript, 216; Vandiwghya, Transcript, 233; Hayab, Transcript, 242. ↩︎

- Danzaria, Transcript, 250, 251–53; Ako, Transcript, 211–12; Vandiwghya, Transcript, 230, 232–33; Danzaria, Transcript, 242–43; Ajayi, Transcript, 280, 282. ↩︎

- Ako, Transcript, 215–16; Danzaria, Transcript, 243–44. ↩︎

- Vandiwghya, Transcript, 230. ↩︎

- David. D. Dagah, Solomon Joseph Munga, and Samuel Shekari, Interviews, Kaduna: Albarka Fellowship Baptist Church, 25 January 2013. ↩︎

- Dauda Danjuma Gata, Bala Haruna Gukut, and D. Madaki Ashere, Interviews, Kaduna: Albarka Fellowship Baptist Church, 25 January 2013. Rev. Musa shared his experience of rejection at worship in Jos by Northern Christians because he was a Pullo at Fulbe National Consultation, Organized by Nigeria Evangelical Mission Association (NEMA), Jos: NEMA Headquarters, 17–20 April 2012. ↩︎

- Ezekiel A. Bamigboye, History of Baptist Work in Northern Nigeria—1901–1975, 59–184; Travis Collins, Baptist Mission of Nigeria (Ibadan: Y-Books, 1993), 42–46; and, S. Ademola Ajayi, Baptist Work in Nigeria—1850–2005 (Ibadan: Book Wright, 2010), 120. ↩︎

- Isaiah Oluwajemiriye Olatoyan, “The Local Church and the Great Commission: A Biblical Perspective on the Practice of Evangelism and Missions among Churches of the Nigerian Baptist Convention” (DMiss diss. Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, 2011), 9–10. ↩︎

- Bamigboye, History of Baptist Work in Northern Nigeria—1901–1975; Collins, Baptist Mission of Nigeria; and, Ajayi, Baptist Work in Nigeria—1850–2005. ↩︎

- See Audi, “World Christianity in Crisis,” Appendix C2. ↩︎

- See Audi, “World Christianity in Crisis,” Appendix C1. ↩︎

- Zacharia Joshua Ako, “The Havoc of Religious Intolerance in Fellowship Baptist Conference,” Paper Presented at Mission Summit of Lagos-East Baptist Conference, March 22, 2014, 11, 12. ↩︎

- See, Audi, An Evaluation of the Homogeneous Presupposition in African Mission. Moses Audi, “Ethnic Plurality and Church Planting in Nigeria,” BETFA 3 (2004): 31–41; Audi, “The Challenge of Ethno-Linguistic Crisis to Missions Effort in Nigeria,” 4–8; Moses Audi, “Heterogeneity and the Nature of the Church: A Biblical and Theological Reflection,” in Contemporary Issues in Systematic Theology: An African Christian Perspective, ed. Moses Audi, Olusayo Oladejo, Emiola Nihinlola, and John Enyinnaya (Ibadan: Sceptre, 2011), 98–112; and, Moses Audi, “Introduction: Heterogeneity of the Kingdom of God” OJOT 12 (2007): 1–4. ↩︎

- Since the early 1980s, the GMB has been appointing people to their ethnic groups as missionaries with very few exceptions on the initiative of the given missionary. ↩︎

- Munga, Interview. ↩︎

- John Femi Adewumi, Interview Transcript, 26 July 2015, 294–96; Danzaria, Transcript, 243–44; Ajayi, Transcript, 286; Babagunda, Transcript, 269. ↩︎

- Adewumi, 295. He noted that the NBC is a leading missionary to the Muslim culture groups in northern Nigeria. ↩︎

- Morgen Morgensen, Fulbe Muslims Encounter Christ: Contextual Communication of the Gospel to Pastoral Fulbe in Northern Nigeria ( Jos: Intercultural Consultancy Services, 2002), acknowledgements. The NBC was a later inclusion for his studies as it was the only denomination that has congregations among the pastoral Fulbe in Nigeria by the time of research. Converts in other denominations are isolated and in integrated congregations. ↩︎

- “Evangelism and Church Growth Development Statistics, 1989–2000,” West Africa/MAP, SUPP. Tables B and D, page 2 of summary analysis. Nigeria is said to have 85–94% of the growth in West Africa. ↩︎

- Most church groups are looking up to Nigeria. The NBC with its eleven theological schools have trained leaders for most of West and Central Africa. The NBC is said to be the second largest denomination outside the United States of America. See “Maisha to Baptist Family: Give Your All to Global Missions,” The Nigerian Baptist, 95 no. 6 ( June 2016): 25. ↩︎

- “Nigerian Baptist leader castigates international community for ignoring terrorism in Nigeria,” Information Service of the Baptist World Alliance, 16 January 2015, http://tinyurl.com/hyg7rgv. ↩︎

- For a list of the international missions points of the GMB/NBC see Audi, “World Christianity in Crisis,” Appendix A. ↩︎

- Adewumi, Transcript, 294–95. ↩︎

- Adewumi, Transcript. ↩︎

- Philip Jenkins, The Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 172–73. ↩︎

- Jenkins, The Next Christendom, 174–75. ↩︎