The Church

Southwestern Journal of Theology

Volume 61, No. 1 – Fall 2018

Editor: W. Madison Grace II

Note1

The present article represents a sort of “detour” from the trail of evidence the present writers followed in previously authoring “Hidden in Plain View: An Overlooked Chiasm in Matt 16:13–18:20.”2 At that point in time, our stated intention for future research was to pursue the ecclesiological implications of additional elegant literary structures we had detected in the portion of the First Gospel after 16:13–18:20 and—to test our ecclesiology-related hypothesis, referred to in the title above as “Matthew’s Proto-Ecclesiology”—in the earlier chapters of Acts.3

To our surprise, though, we found that the first half of Acts contains numerous literary structures remarkably like Matthew 16:13–18:20 (plus others later in the First Gospel).4 More surprising, and even more significant in our minds, was that certain crucial theological emphases in Matthew 16:13–18:20 dovetailed closely with some of the most important theological themes in Acts 1–14.

What were we to make of this quite unexpected phenomenon? That is what this article laying out our “Plan B” research is about: charting and interpreting the meaning and significance of this largely undeveloped Matthean-Lukan theological interface. In doing so, the present writers realize full well that there may be other plausible explanations for the pattern we have observed.5 Up to this point, though, we have been unable to find or hypothesize other views that accord with the evidence as well as what we have chosen to call here “Matthean Theological Priority.”6

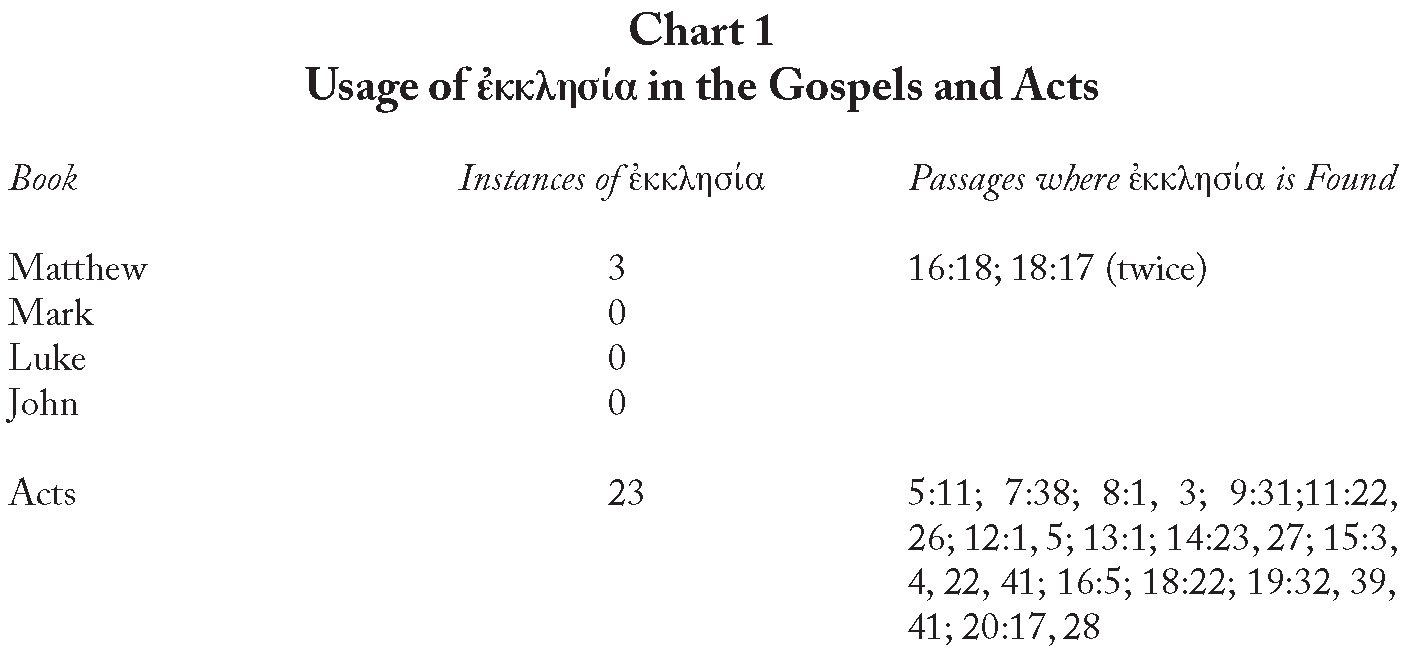

Toward that end, because of space limitations, this presentation will focus only on the usage pattern of ἐκκλησία7 and its significance in the Gospels and Acts 1–14. The study will proceed in the following manner: First, simply laying out the uses of ἐκκλησία in the Gospels and Acts; second, discussing the odd pattern of non-usage of ἐκκλησία in the Third Gospel, then considerable usage in Acts; third, discussing the apparently seamless dovetailing of the Matthean use of ἐκκλησία with that of Acts; and finally, putting an appropriate descriptive name on this data (i.e., in this case, “Matthean Theological Priority”) and briefly previewing its possible viability and impact.

The Presence—and Absence—of ἐκκλησία in the Gospels and Acts

The Greek term ἐκκλησία is used 113 times in the entire New Testament. However, only three of those uses are in Gospels. By contrast, there are 23 inclusions of ἐκκλησία in the Acts of the Apostles,8 19 of which refer to the church.9

As seen in Chart 1, all three uses of ἐκκλησία in the Gospels are found in Matthew. There are no uses of ἐκκλησία in Mark, Luke, or John.

Let that sink in for a moment. Far more than a merely unusual statistical observation from a basic concordance study, the fact that the foundational ecclesiological term used in the New Testament (i.e., ἐκκλησία) is found among the Gospels only in Matthew is nothing less than astounding! After all, at the very least, Matthew is, with relatively little controversy, the most Jewish of the Gospels, which is, at first—or even second or third—glance, a seemingly odd place to find Jesus’s teaching on the church.

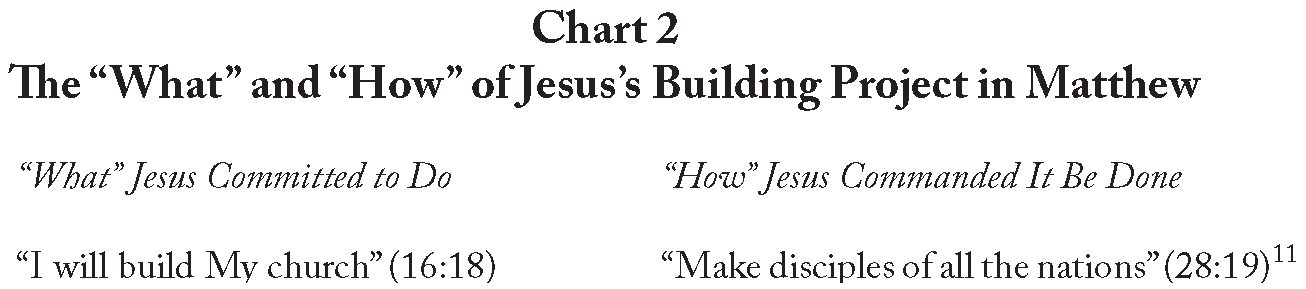

Now, this is not to say that important ecclesiology-related terminology does not occur in the other Gospels. For example, μαθητής (“disciple”) is found frequently in Mark (45 uses), Luke (38 uses) and John (80 times).10 Even then, as seen in Chart 2, it is only in Matthew (which includes 75 uses of μαθητής), that the interchangeability of the plural μαθηταὶ (“disciples”) with ἐκκλησία is reasonably apparent.

Note11

Whether by the explicit inclusions of ἐκκλησία or the indirect presence of disciples (μαθηταὶ), the building blocks of the church,12 Matthew is the only Gospel that clearly points beyond the Death, Resurrection, and Ascension of Jesus to the beginning of Christ’s church. In the chronological succession of New Testament history,13 that, of course, is precisely where the Book of Acts is found.

An Excursus on Richard Bauckham’s Jesus and the Eyewitnesses14

Among the most significant recent volumes to appear dealing with the Gospels is Bauckham’s thorough and lengthy (538 pages) treatment applying the existing cultural concept of “eyewitness” to the Gospels. For the focused purposes of this presentation, Bauckham’s most significant findings/conclusions are: (1) The way in which “eyewitness” testimony was passed on in the New Testament era completely precludes the still common ideas of lengthy oral tradition that changed to a significant degree over that time; and (2) The Gospels were produced either by such meticulous “eyewitnesses” or by those whose research was strongly dependent on just such “eyewitness testimony.”

While these and other conclusions drawn by Bauckham are ground-breaking for wider scholarly study of the Gospels, he, like other broadly evangelical senior British scholars, does not conclude that the Apostle Mat- thew wrote the First Gospel.15 However, that is not the case for most recent significant North American evangelical commentators on Matthew, who do hold that Matthean authorship of the First Gospel is most probable.16

In denying that the Apostle Matthew wrote the Gospel by his name, Bauckham states he is unable to equate the conversion accounts of Matthew (Matt 9:9) and Levi (Mark 2:14; Luke 5:27–28), the common evangelical view. However, besides assuming Levi was an alternate name for Matthew, there is another quite plausible understanding: that the Levi described in Mark 2:14 as “the son of Alphaeus” is the brother of another Apostle, James the son of Alphaeus, who is described as such in all four listing of the Apostles of Jesus (Matt 10:3; Mark 3:18; Luke 6:15; Acts 1:13).

This view is the conclusion of Tal Ilan,17 of which, interestingly, Bauckham says “This may be correct,”18 though he ultimately disagrees without presenting any evidence for why he does so. Also, if James the son of Alphaeus is the same person as Ἰάκωβος ὁ μίκρος (which can be rendered as either “James the less, “James the younger” or “James the small/short” [Mark 15:40]), then this relatively-unknown apostle’s family was quite well-known in early Christianity. For instance:

- James the short’s mother, Mary, followed and helped Jesus while He was ministering in Galilee (Mark 15:41), witnessed Jesus’s death (15:40) burial (15:47);

- This Mary, her daughter Salome, along with Mary Magdalene, witnessed the empty tomb on the first day of the week (16:1–8);

- Yet another son of Mary’s, named Joses—presumably known by the readers—is mentioned in Mark 15:40, 47.

If the family of James the son of Alphaeus indeed was as prominent as these verses suggest, the conversion of Levi, James’s brother, would indeed have been significant enough for Mark (2:14) and Luke (5:27–28) to record. In such a case, the conversion of Matthew should be understood to have occurred alongside Levi’s conversion, on the same occasion. The following celebratory banquet is expressly stated as taking place at Levi’s house (Luke 5:29 [Mark 2:15 says “his house,” clearly speaking of Levi]). Matthew 9:10 simply reads “the house” (τῇ οἰκίᾳ), implying Matthew, though an honored guest, was also one of several tax collectors (Matt 9:10–11) in attendance at the festive occasion at the home of Levi (Mark 2:15–16; Luke 5:29–30).

If Matthew did write the Gospel bearing his name, then he, along with John,19 are “eyewitness” Gospel authors. That assertion stands in contrast to Mark20 and Luke,21 both of whom wrote (in different ways) “researched” Gospels. This important distinction will be returned to later in the paper.

The Head-Scratching ἐκκλησία “Off and On” Switch in Luke-Acts

There is nothing strange in and of itself that Acts contains 19 uses of ἐκκλησία in reference to the church of Jesus Christ, 12 of which occur in chapters 1–14. However, there is something quite strange indeed when one considers that the Gospel of Luke has no inclusions of ἐκκλησία at all.

Given that Acts is the second volume of Luke’s two-volume work on Jesus and the early church,22 where does the theological impulse toward the extensive development of the ἐκκλησία in Acts come from? It is as if there is a light switch that is “Off ” throughout the Gospel of Luke, then is suddenly switched “On” in Acts. In other words, how is it (i.e, on what textual basis) that the church suddenly “shows up” and is spotlighted in Acts when it is not mentioned at all in the Gospel of Luke?

Were it not for the formal prologue to the Third Gospel (Luke 1:1–4), that observation might remain completely mired in speculation. Fortunately, however, Luke, despite the use of technical and rare terminology,23 does describe the careful methodology he utilized in his research clearly enough to answer at least some of the most pointed questions about the relationship between the Third Gospel and Acts regarding ecclesiology, as well as provide seemingly helpful implications concerning other questions.24

Many have undertaken to compile a narrative about the events that have been fulfilled among us, just as the original eyewitnesses and servants of the Word handed them down to us. It also seemed good to me, since I have carefully investigated everything from the very first, to write to you in orderly sequence, most honorable Theophilus, so that you may know the certainty of the things about which you have been instructed (Luke 1:1–4, HCSB).

For the purposes of this presentation, as seen in Chart 3, Luke 1:1–4 can be helpfully broken down25 in the following manner:

Chart 3

Stated Elements of Luke’s Approach to Research and Writing

Abundance of written sources: Many (previously existing) narratives about “the events fulfilled among us” (i.e., centering on Jesus; 1:1).26

Culturally-expected means of transmission: Traditions being “passed on,” “committed” or “handed down” (i.e., to hearers or the next generation; 1:2a).27

Trustworthy human sources: “Eyewitnesses28 and “ministers”/ “servants”29 of the Word “from the beginning”30 (1:2b).

Stated research methodology: Careful investigation31 of everything from the beginning (1:3a).32

Stated writing style: accurately33 and orderly34 (1:3b).

Intended outcome for the audience:35 knowing “the full truthfulness”36 of what Theophilus had previously been taught (i.e., about Jesus and his life and ministry; 1:4).37

The most significant relevant wording found in the preface to the Third Gospel is the terminology Luke utilized for his human sources: αὐτόπτης (“eyewitness”) and ὑπηρέτης (“assistant, servant”). Alexander’s explanation for why Luke uses αὐτόπτης in Luke 1:2, a word found only here in the New Testament, instead of the much more common μάρτυς (“witness”) is: “Luke goes out of his way to avoid explicitly Christian language in the preface.”38 But, could there also be additional considerations for the choice of αὐτόπτης here?

It appears to depend on precisely how the relationship between αὐτόπται and ὑπηρέται is understood. Recent commentators generally agree with Alexander’s view that this term speaks of “[T]wo roles: ‘ministers of the word’ … who have ‘first-hand experience’ of the facts they report.”39 However, Craig Evans states: “‘Eyewitnesses’ refers to the original disciples who became Jesus’s apostles and were eyewitnesses of his life and ministry.”40 If Evans’s understanding is correct, Matthew and John fit into the Lukan category of αὐτόπται (“eyewitnesses”). Certainly, Mark would fit as part of the ὑπηρέται (“assistant, servant”), given that he is expressly referred to as the ὑπηρέτην of Barnabas and Saul in Acts 13:5 and surely later played a similar role with Peter (1 Pet 5:13).

The long-held scholarly consensus of Markan priority assumes that the Gospel of Mark would be a written source for Luke “about the events fulfilled among us” referred to in Luke 1:1.41 The fact that there are no instances of ἐκκλησία in Mark matches with the absence of ἐκκλησία from the Third Gospel. However, the textual reality that ἐκκλησία is entirely absent from the Gospel of Luke, while being on prominent display in Acts, demands an explanation.

Since, as seen above, the Gospel of Matthew includes three uses of ἐκκλησία—which fit hand in glove with the uses of ἐκκλησία in Acts—the most obvious explanation seems to be that the First Gospel is Luke’s source for his ecclesiological content in Acts. Is that plausible?

Yes. Until around AD 1800, virtually no extant writing expressed any other view than that the reason why Matthew is placed first in the order of the Gospels is because it was written first.42 However, while it is not the purpose of this presentation to argue for Matthean Priority, based on the observation that Luke apparently drew upon the First Gospel in writing Acts, it also seems reasonable to hypothesize that the Gospel of Matthew was available—in some form, at least—when Luke conducted his research toward writing both the Third Gospel and Acts.

What is meant here by “in some form” is that Luke apparently did not get his Matthean-oriented understanding of the ἐκκλησία that is played out in Acts 1–14 from a theoretical “Q” source. Had he done so, Luke certainly would have included material like Matthew 16:18 and 18:17 in the Third Gospel. It is possible, though, as Papias’s phraseology has been taken by not a few over the centuries, that the initial published version of Matthew was written in Hebrew or Aramaic and may have predated the Gospel of Mark.43

If it is the case, though, that Luke drew from the Gospel of Matthew in writing Acts, again, how can the absence of ἐκκλησία in the Third Gospel best be explained? A less likely possibility exists to explain the ἐκκλησία–related silence in the Gospel of Luke: The Gospel of Matthew could have appeared during the time between the publication of the Third Gospel and the Book of Acts. If so, Matthew would have made available to Luke to inform the inclusions of ἐκκλησία in Acts 1–14. However, since it is common for scholars to date the authorship of the Gospel of Luke and the Book of Acts no more than three years apart, and Matthew and Luke may well have been in distant parts of the Roman Empire when they were writing, the time window is probably too narrow to allow for the copying and spread/ availability of the First Gospel to wherever Luke may have been as he was preparing to write Acts.

Thus, the more likely thesis is that the Gospel of Matthew—in some form—existed and was accessed for Luke’s researching toward writing the Third Gospel (and Acts). However, Luke still apparently, for some reason, chose not to utilize the ecclesiology-related material in Matthew until he wrote Acts.

Evans is correct when he, in his discussion of the authorship of the Gospel of Matthew, observes that, “until the nineteenth century,” Matthew was not only considered to be the earliest of the Gospels, but also the most appreciated.44 And, if, as noted above, Matthew fits into Luke’s category of “eyewitnesses” and Mark was in the “assistant/servant” category (Luke 1:2), the First Gospel naturally would have been held in at least somewhat higher esteem than the Second Gospel by Luke in his research. Could just such a sense of comparative theological importance be an important clue as to why the Gospel of Luke does not include anything remotely like the ἐκκλησία material in the Gospel of Matthew?

The Head-Scratching ἐκκλησία “On” Switch

Moving from Matthew to Acts

As discussed above, bringing the First Gospel into play at this point unquestionably brings light to bear on the issue at hand. Analogically, the Gospel of Matthew is like a light previously switched “On” regarding the material having to do with the life and ministry of Jesus that continues to cast light on the material in the Book of Acts. The fact that the “church” material is found in a Gospel (Matthew) that is not part of the matched pair of books written by Luke, usually called Luke-Acts, is, of course, where the rub lies.

However this Matthew feeding into Acts phenomenon initially strikes the reader, it is unquestionable that it exists. Substantial backing for this claim is found in Chart 4:

Chart 4

Clear Echoes of Matthew’s Proto-Ecclesiology in Acts 1–14

- Flowing from Jesus’s assertion “I will build My church” (Matt 16:18) are the development of local churches in: (1) Jerusalem (see the uses of ἐκκλησία in Acts 5:11; 8:1, 3; 11:22; and 12:1, 5); (2) Judea, Galilee, and Samaria (9:31); (3) Syrian Antioch (11:26; 13:1; 14:27); and (4) Derbe, Lystra, Iconium, and Pisidian Antioch (14:23).

- Matthew 16:18 says Jesus “will build” (future tense of οἰκοδομέω), stating that Jesus’s church-building project would begin at some point in the future) and, in Acts 9:31, Luke says the building process (again οἰκοδομέω) is in progress “throughout all Judea, Galilee and Samaria” (HCSB);

- Matthew 16:18–19 envisions a unique leadership role for Simon Peter in the church Jesus would build, which certainly is fulfilled in what is seen of Peter’s ministry in Acts 2–12;

- As mentioned above, the Gospel of Matthew strongly implies that the method by which Jesus’s church would be built would be through the carrying out of the Matthean Great Commission to “make disciples.” Not coincidentally, the only other place in the New Testament in which the verb μαθητεύω (to “make disciples”) is found besides in Matthew (13:52: 27:57; 28:19) is in Acts 14:21;

- Further identifying Jesus’s intended church-building process as making disciples is seen in the interchangeability of ἐκκλησία and the plural μαθηταὶ(“disciples”) in the following five pairings of verses in Acts 1–14:

- 5:11 and 6:1 (in Jerusalem);

- 8:1 and 9:1 (in Jerusalem and disciples from Jerusalem fleeing to Damascus);

- 3. 11:26 (in Syrian Antioch, before the first missionary journey [Note that “Christians” is also interchangeable with ἐκκλησία and μαθηταὶ here]);

- 14:22, 23 (Derbe, Lystra, Iconium, Pisidian Antioch);

- 14:27, 28 (Syrian Antioch, at the end of the first missionary journey).

In each pairing, ἐκκλησία views the believers corporately and μαθηταὶ views them as a group of individuals. It can be memorably—but accurately— said that, in Acts, the “church” is the disciples gathered (often in worship) and the “disciples” are the church scattered (to do ministry as they live day-by-day).45

In summary, it certainly must be admitted that other explanations for the phenomena treated in this paper may be possible. Yet, if the Apostle Matthew did write the Gospel that goes by his name, which removes Bauckham’s misgivings about giving any serious consideration of the author of the First Gospel as an “eyewitness,”46 then the best alternative as to why Luke echoes the Proto-Ecclesiology of the Gospel of Matthew in Acts 1–14, but does not cite the First Gospel in the Gospel of Luke is out of respect for Matthew’s “eyewitness”/apostolic role: not wanting to duplicate the highly-respected predictive ecclesiology of the Gospel of Matthew.

Although this statement may, on initial reaction, seem to contradict Luke’s stated research methodology in Luke 1:1–4, there is no wording in his preface that requires that Luke record everything in the Third Gospel that he found in his research. As seen in Chart 3 (above), all that Luke claims to be doing is:

- to “give close attention” (παρακολουθέω; 1:3) to what his sources (including αὐτόπται and ὑπηρέται; 1:2) said, starting “from the beginning” (ἀπ’ ἀρχῆς and ἄνωθεν;1:2, 3);

- to be able to present an “accurate” (ἀκριβῶς; 1:3), “orderly” (καθεξῆς; 1:3) and “fully truthful” (ἀσφάλειαν; 1:4) account of the life and ministry of Jesus to Theophilus (1:3).

Thus, by his own stated standards, Luke did his job in writing the Third Gospel exceedingly well. That is the case even though Luke did not choose, in his Gospel, to reproduce the proto-ecclesiology found in Matthew’s Gospel, confident that his readers would hear—or had already heard—of Jesus’s stated intent to build His ἐκκλησία (Matt 16:18) and the Matthean Great Commission (28:19–20) through the First Gospel before they read the Book of Acts. Though speculative as to why Luke might have made that choice, it is plausible he decided to construct the Third Gospel to substantially complement47 the content already available in Matthew (and Mark) with much he found in his research (Luke 1:1–4) about the life and ministry of Jesus, then develop the fulfilling of the Matthean proto-Ecclesiology in his second volume about the early church: Acts.

Conclusion: Is “Matthean Theological Priority” a Viable View?

The case for “Matthean Theological Priority” presented here is not intended to argue directly for Matthean priority in the sense that Matthew was the first Gospel to have been written.48 That highly complex issue was far too broad to undertake in such limited space.

Does this presentation answer all the questions about the Matthean Theological Priority it concludes does exist, though? Hardly, and each reader must make up his or her own mind concerning what has been said. Indeed, what has been laid out here will undoubtedly raise many more questions that need to be addressed, including numerous implications yet to be noticed, much less carefully considered.

It is worth saying in closing, however, that, despite the long and often insightful history of the study of the Synoptic Gospels, it is high time to recognize that the Gospel of Matthew has, to a large extent, often been treated with somewhat less theological respect—or at least hesitantly—by those holding to, and playing off, their presupposition of Markan priority and its implications.49 By contrast, what has been argued in this paper is the idea that significant evidence exists, not just in the virtually unanimous viewpoint of the earlier centuries of church history, but also clustering around the non-use of ἐκκλησία in the Third Gospel, that suggests Luke considered the Gospel of Matthew to be: (1) more significant than Mark as a source for the theological content that informed his extensive ecclesiological references in Acts; and (2) worth respecting/honoring by choosing not to repeat what he knew regarding Matthew’s proto-ecclesiology in authoring the Third Gospel, but instead built upon it in the Book of Acts.

The court of theological appeals will weigh in on the new view set forth here in due time. As that takes place, no matter the wider response, it is sincerely hoped that the concern expressed here for a stronger, and thus healthier and more balanced, perspective on the theological contribution of Matthew’s Gospel will be the result. Even if nothing else were to come about from this initial framing and presentation of Matthean Theological Priority, the present writers would be most grateful for that worthy outcome.

- By “Matthean Proto-Ecclesiology” is meant the ecclesiological-related material that exists between the chiastic structuring of Matt 16:13-18:20 the present writers expounded in “Hidden in Plain View” (see footnote 2) and the generally understood beginning point of the Church of Jesus Christ in Acts (or perhaps the first inclusion of ekklēsia in Acts in 5:11). ↩︎

- A. Boyd Luter and Nicholas A. Dodson “Hidden in Plain View: An Overlooked Chiasm in Matt 16:13–18:20,” Filologia Neotestamentaria XXVIII (2016): 23–37. ↩︎

- Filologia Neotestamentaria XXVIII 2016, 36. ↩︎

- Which we hope to publish, Deo volente, as time allows in our busy schedules. ↩︎

- It is our sincere hope that other scholars would come alongside the research/conclusions we lay out here and offer what might prove to be yet more compelling arguments or alternate solutions. ↩︎

- As will be explained, our coined title—which we settled on simply for lack of a more accurate way to describe what we mean—should not be confused with the well-known (i.e., from the history of interpretation of the Gospels, at least) concept of Matthean Priority (i.e., as opposed to Markan Priority). ↩︎

- In several cases, other important evidence for this view beyond the usage of ekklēsia or related issues will be treated summarily in footnotes. ↩︎

- W.F. Moulton, A.S. Geden, and H.K. Moulton, A Concordance to the Greek Testament, 5th ed. (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1978), 316. ↩︎

- Acts 7:38 refers to the worshipping community of Israel in the wilderness—in keeping with common LXX usage—and Acts 19:32, 39, 41 refer to a chaotic secular “assembly” in Ephesus—in keeping with wider secular usage of the era. ↩︎

- Moulton, et al., A Concordance to the Greek Testament, 608–11. ↩︎

- Nicholas Dodson and A. Boyd Luter, “Mathētaical Ecclesiology: An Exegetical Examination of Disciples as the Church,” unpublished paper presented at the 2015 Everyday Theology Conference, Liberty University. See also Luter and Dodson, “Matured Discipleship: Leadership in the Synoptics and Acts,” Chapter 22 in Biblical Leadership: Theology for the Everyday Leader, Benjamin Forrest and Chet Roden, eds. (Grand Rapids: Kregel, 2017) 334– 48; and Luter and Dodson, “Hidden in Plain View.” ↩︎

- As will be explained below, this concept of the disciples being the building blocks of the church, implied strongly in Matthew, is clearly seen in Acts in five different passages in chapters 1-14. ↩︎

- This is not a naïve claim that all the Gospels were written before the Book of Acts, just an affirmation that the events recorded in the Gospels focus on the life and ministry of Jesus, which historically precedes the events recorded in Acts. ↩︎

- Richard Bauckham, Jesus and the Eyewitnesses: The Gospels as Eyewitness Testimony (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2006). ↩︎

- Bauckham, c 108–12. See the similar conclusions related to the authorship of the Gospel of Matthew by e.g., John Nolland, The Gospel of Matthew NIGTC (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2005); and R.T. France, The Gospel of Matthew NICNT (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2007). ↩︎

- E.g., Michael J. Wilkins, Matthew NIVAC (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2004), 22; David L. Turner, Matthew BECNT (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2008), 11–13; Grant R. Osborne, Matthew, Zondervan Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2010), 33–35; and Craig A. Evans, Matthew New Cambridge Bible Commentary (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 3. Evans goes so far as to say that, until the nineteenth century AD, “[T]here is not a hint that anyone claimed someone else as the author of Matthew” (3). ↩︎

- Tal Ilan, Lexicon of Jewish Names in Late Antiquity: Part I: Palestine 330 BCE–200 CE (Tubingen: Mohr, 2002). ↩︎

- Bauckham, Jesus and the Eyewitnesses, 87. ↩︎

- It is assumed here that the Apostle John wrote the Fourth Gospel at a point in time considerably later in the first century AD, the majority evangelical view. ↩︎

- It is assumed that Mark wrote the Second Gospel, drawing largely on the teaching and eyewitness memory of Simon Peter, a common evangelical view. ↩︎

- Luke’s research and writing methodology laid out in Luke 1:1–4 is assumed here, with particular emphasis on his use of αὐτόπται (“eyewitnesses”) and ὑπηρέται (“assistants, servants”) in 1:2. See also the discussion in the next section of this presentation. ↩︎

- Acts 1:1a clearly states “I did the first narrative” (i.e., the Gospel of Luke, translation ours; italics ours). ↩︎

- See the discussion just below for evidence for this claim. ↩︎

- In her influential study, The Preface to Luke’s Gospel: Literary convention and social context in Luke 1.1.4 and Acts 1.1 SNTSMS 78 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), Loveday Alexander discusses at some length the rare—at least biblically—terms. ↩︎

- More in-depth significant discussions of Luke 1:1-4 are, e.g., Alexander, 102-142; and Bauckham, 116-124. ↩︎

- BAGD, “διήγησις,” 195. This term is a hapax legomenon. ↩︎

- BAGD, “παραδίδομι,” meaning 3, 615. ↩︎

- BAGD, “αὐτόπτης,” 122. This term is also a hapax legomenon, though its meaning is

well-attested in extrabiblical usage (e.g., Alexander, The Preface to Luke’s Gospel, 120–23). ↩︎ - BAGD, “ὑπηρέτης,” 842. ↩︎

- Rendering the phrase ἀπ’ ἀρχῆς, this wording in Luke 1:2 is clearly parallel in thought to ἄνωθεν in 1:3. ↩︎

- BAGD, “παρακολουθέω,” meaning 3, 619. ↩︎

- Though a different Greek term is used (ἄνωθεν), the idea of “from the beginning” is purposefully repeated from Acts 1:2 (see footnote 28 above). ↩︎

- BAGD, “ἀκριβῶς,” 33. ↩︎

- BAGD, “καθεξῆς,” 388. ↩︎

- The original reader was “most excellent Theophilus” (Acts 1:3c), but also all later audiences of Scripture (2 Tim 3:16; see 1 Tim 5:18, in which Paul equates a statement from the Gospel of Luke [10:7] with a quotation from Deut 25:4 as both being “Scripture”). ↩︎

- BAGD, “ἀσφάλεια,” meaning 1.b., 118. ↩︎

- A very thorough treatment of this passage and what it entails is found in Alexander, The Preface to Luke’s Gospel, 102–42. ↩︎

- Alexander, The Preface to Luke’s Gospel, 124. ↩︎

- The Preface to Luke’s Gospel, 123. See, e.g., Darrell L. Bock, Luke NIVAC (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1996), 42, who renders ὑπηρέται as “servants” (of the word). ↩︎

- Craig A. Evans, Luke New International Bible Commentary (Peabody: Hendrickson, 1990), 20. ↩︎

- It is almost as common for scholars to believe that Luke also utilized the hypothetical document “Q.” ↩︎

- And, that is a possible implication of the widely-known words of Papias, one of the apostolic fathers, who is cited by the early church historian, Eusebius. Currently, the most accessible translation of the various fragments of Papias’s greatest work, Exposition of the Logia of the Lord, is in J.B. Lightfoot, H.R. Harmer, and M.W. Holmes, The Apostolic Fathers (Leicester: Apollos, 1990), 307–29. ↩︎

- See the extended discussion of Papias’s wording in Bauckham, Jesus and the Eyewitnesses, 202–39. ↩︎

- Evans, Matthew, 3. His word is “favorite.” ↩︎

- See Dodson and Luter, “Mathetaical Ecclesiology;” Luter and Dodson, “Leadership as Matured Discipleship;” and Luter and Dodson, “Hidden in Plain View.” ↩︎

- Even given Bauckham’s rejection of Matthean authorship of the First Gospel, there is still surprisingly little having to do with the authorship of Matthew—or even the Gospel by his name—in his “Index of Scriptures and Other Ancient Writings” at the end of Jesus and the Eyewitnesses, particularly when compared with the large number of instances in which he handles the Gospels of Mark, Luke, and John (526–31). While it is perhaps too strong to characterize Bauckham’s apparent hesitancy to cite the First Gospel as anti-Matthean bias, at least statistically speaking, it certainly appears to be “Matthean minimizing.” ↩︎

- It is generally agreed that the percentage of material unique to the Gospel of Luke (i.e., among the Gospels) is roughly 60%. ↩︎

- A treatment defending Matthean priority in a fresh manner is D.A. Black, Why Four Gospels: The Historical Origins of the Gospels (Grand Rapids: Kregel, 2001). The updated and revised version of this work is D.A. Black, Why Four Gospels: The Historical Origins of the Gospels rev. ed. (Gonzalez, FL: Energion, 2011). ↩︎

- Note, e.g., Bauckham’s wording: “So, assuming the priority of Mark’s Gospel to Matthew’s…” Bauckham, Jesus and the Eyewitnesses, 110, (italics ours). ↩︎