Discipleship

Southwestern Journal of Theology

Volume 50, No. 2 - Spring 2008

Managing Editor: Malcolm B. Yarnell III

In Revolution: Finding Vibrant Faith Beyond the Walls of theSanctuary, George Barna identifies what he calls a transformation in the process by which millions of believers are growing in Christ. According to Barna, many of these “revolutionaries” are leaving the local church in an effort to experience purposeful spiritual growth outside the structure and authority of what they consider to be an ineffective model for achieving God’s purposes in contemporary society. Barna points out, and rightly so, that local churches are not achieving stellar results in transforming the lives and worldviews of their members.He endorses a self-serving discipleship process in which believers piece “together spiritual elements they deem worthwhile, constituting millions of personalized ‘church’ models.”1 However, Barna’s solution to the problem is to disregard a biblical understanding of the local church and disregard the role of the church in the disciple-making process.2 He also predicts that by 2025, the local church will be rendered irrelevant, as millions of born-again Christians sever their institutional and denominational ties in favor of “alternative faith-based communities” and ministries focusing on media, arts, and culture.3

My intent is not to argue with Barna regarding the integrity of his research, or to disregard the existence of these so-called “revolutionary” Christians. There may or may not be, as Barna concludes, over 20 million believers who are bypassing the local church in their efforts to achieve significant spiritual growth.4 What I would argue, however, is that the local church is a biblically-ordained and relevant vehicle for transformational discipleship. Additionally, I would suggest that the church was given the primary responsibility for making disciples. Therefore, relegating the task to individual choice, para-church organizations, or “faith-based communities” is a dereliction of our mission. Jesus commissioned those who would become the formative core of the early church to make disciples.5 If that mandate is not being carried out effectively in the context of the local church, the solution is not to abandon the mission, but to strengthen our efforts at accomplishing the charge.

The purpose for this article is to call the local church to renew her commitment to growing authentic disciples, and to reform a discipleship process that we have been using for too long with lackluster results. In many churches, where discipleship is seen as just a component of its mission, the process takes the form of programs for motivated learners or an elective track for the truly committed. What I propose is an integrative model for discipleship in the local church. In this model, discipleship is not just one component of the church, but a guiding value that permeates every ministry area. The model begins by envisioning a biblical paradigm for the result of the process that answers the question, “Who is a disciple?” The second element of the model presents the functions of the church as disciple-making tools, answering the question, “What is discipleship?” The third element includes the options for delivering spiritual growth experiences, and answers the question, “How do we make disciples?” When these three elements are merged, both philosophically and pragmatically, the result should be transformed disciples and healthy churches.

Before a more detailed explanation of the model, I will define three important terms in light of their relevance to the meaning and functioning of the model. These words are disciple, discipleship, and church.

Disciple

The word “disciple” occurs at least 230 times in the Gospels and 28 times in Acts.6 Literally, disciple means learner; the Greek word mathetes is the root of our word mathematics, which means “thought accompanied by endeavor.”7 Disciples think and learn, but they also move beyond learning to doing—the endeavor. Even in Jesus’ time, disciples were those who were more than pupils in school, they were apprentices in the work of their master.8

The essence of the word disciple changed from the first time it is used in Matthew 5:1 to the last mention in Acts 21:16. In the gospels, disciple already had a meaning before Jesus used the word. In the first century, the cultural understanding of a disciple was one who was more than just a learner; the disciple was also a “follower” (once again we see the connection between thinking and doing).9 Throughout the Greco-Roman world, great teachers were making disciples. Philosophers like Socrates had devoted followers who were trained under the guidance of an exemplary life. Disciples spent time with their master and became learning sponges, soaking up the teaching and example of the one from whom they were learning. Rabbis like Hillel and Shammai had disciples who learned how to interpret the Scriptures and relate them to life. The Bible also tells us that there were disciples of the traditions of Moses ( John 9:28) and that John the Baptist had disciples (Matt 9:14, 11:7, 14:2), some of whom joined Jesus’ mission.10

Initially, all of Jesus’ followers were referred to as disciples; but what we generally think of as the “disciples” today are the twelve men whom Jesus chose to train and send out for His kingdom work. This group was the seedbed of the incipient church. Before Jesus ascended to the Father, He gave His disciples—now apostles—the responsibility to go and make disciples as He had done. The qualifications for true disciples were: (1) Belief in Jesus as messiah ( John 2:11, 6:68–69); (2) Commitment to identify with Him through baptism; (3) Obedience to his teaching and submission to his Lordship (Matt 19:23–30, Luke 14:25–33).11

In the book of Acts, Luke uses the term disciple to describe all followers of Jesus Christ.12 He also mentions that these believers were first called Christians at Antioch, but this is one of only two times he uses this word, and in both occasions the term is used by outsiders.13 In addition, these disciples are usually mentioned in light of their relationship to a particular city, implying their association with a local group of believers.14 Consequently, we can assume that, in the New Testament church, followers of Jesus Christ considered themselves to be a part of a local body of believers—the church—and they understood their role within that body to be as a disciple.

There is an “identity crisis” in contemporary Christianity that is forestalling spiritual growth in the lives of believers and is eroding the health of the local church. This is not a contemporary crisis; Bonhoeffer warned that the church had “evolved a fatal conception of the double standard—a maximum and minimum standard of Christian obedience.”15 Hull describes the problem that lingers even today:

16The common teaching is that a Christian is someone who by faith accepts Jesus as Savior, receives eternal life, and is safe and secure in the family of God; a disciple is a more serious Christian active in the practice of the spiritual disciplines and engaged in evangelizing and training others. But I must be blunt: I find no biblical evidence for the separation of Christian from disciple.

Although there is only anecdotal evidence to substantiate Hull’s claim, the proof is in the lack of power in the lives of most believers and the general effectiveness of the church in making an impact on society and accomplishing the Great Commission. The longer that we perpetuate the myth that disciple is a secondary identity reserved for the elite, the more we will continue to produce “bar-code Christians” who are following after a “non-discipleship Christianity.”17 Everyone who expresses faith in Jesus Christ as Lord and Savior becomes a disciple and, by implication, begins a lifelong, Spirit-led journey of growth and formation in the likeness of the One whom they follow.

Discipleship

Disciples of Jesus Christ fulfill their calling through discipleship: “the process of following Jesus”.18 Although the word discipleship does not appear in the New Testament, the concept is implied through Jesus’ command in the Great Commission to make disciples. The suffix “ship” is derived from the Old English “scipe,” meaning “the state of,” “contained in,” or “condition”. Discipleship is the state of being a disciple; we are always in the condition of being disciples—loving Christ and obeying our Master. Another idea expressed through this suffix is “an art, skill, or craft.”19 Discipleship is not only an internal condition of believers, but also involves the active manifestation of their relationship with Jesus Christ.

Another common word derived from the suffix “scipe” is “shape,” which means to create or form.20 In Galatians 4:19, Paul writes: “My dear children for whom I am again in the pains of childbirth until Christ is formed in you, how I wish I could be with you now.” Here, Paul expresses a longing to see spiritual formation occur in the lives of the Galatian disciples—that their discipleship would produce changed lives and provide evidence that transformation was occurring. Spiritual formation is the sanctification or transformation that happens during the process of intentional discipleship. While some would argue that spiritual formation is the process of growth in Christ, or that it is a systematic inculcation of disciplines, I would suggest that formation is the result of discipleship.21 Through discipleship, followers of Jesus Christ are formed into an ever-clearer image of him.

Church

In article VI of the Baptist Faith and Message (2000), the nature of the church is described:

A New Testament church of the Lord Jesus Christ is an autonomous local congregation of baptized believers, associated by covenant in the faith and fellowship of the gospel; observing the two ordinances of Christ, governed by His laws, exercising the gifts, rights, and privileges invested in them by His Word, and seeking to extend the gospel to the ends of the earth.22

The local autonomous church is the model that is affirmed in Scripture. According to Hobbs, “the word ‘church’ never refers to organized Christianity or a group of churches” but to either the local body of Christ or the church universal.23 The above statement also affirms the mission of the local church: “to extend the gospel to the ends of the earth.” Acts 1:8 is the force behind the evangelistic thrust of the church and Mattew 28:18– 20 describes the work that is to be done by the church in the fulfillment of her mission: making disciples.

The local church is composed of disciples who should be investing themselves in the lives of other disciples. The process of following Jesus— discipleship—is the curriculum of this Christ-focused school for making disciples. In Acts 2:42–47, we see a glimpse of the way in which the early church practiced the disciple-making task: “add[ing] to their number . . . teaching . . . fellowship . . . praising God . . . [giving] to anyone as he had need.” This passage serves as a curricular outline for the priorities of both the local body and the individual disciple after baptism (Acts 2:41): continuing evangelism, teaching, fellowship, worship, and ministry.

Instead of consigning discipleship to a program of the church, we should be magnifying its missional role. The health and strength of a local church hinges on her effectiveness in making disciples. Unfortunately, according to Ogden, there are some who believe that the church is irrelevant to the discipleship process.24 However, unless local churches make committed disciples, all the evangelism, teaching, fellowship, worship, and ministry will be empty and powerless.

An Integrative Model

Raising up successive generations of committed disciples is the responsibility of the local church. While this maxim may be obvious, the reality is that far too many churches have abandoned intentional discipleship. Instead, the church must reclaim her role as disciple-maker. Wilhoit clearly defines the local church’s assignment:

Spiritual formation is the task of the church. Period. It represents neither an interesting, optional pursuit by the church nor an insignificant category in the job description of the body. Spiritual formation is at the heart of its whole purpose for existence. The church was formed to form. Our charge, given by Jesus himself, is to make disciples, baptize them, and teach these new disciples to obey his commands. The witness, worship, teaching, and compassion that the church is to practice all require that Christians be spiritually formed. [t]he fact remains that spiritual formation has not been the priority in the North American church that it should be.25

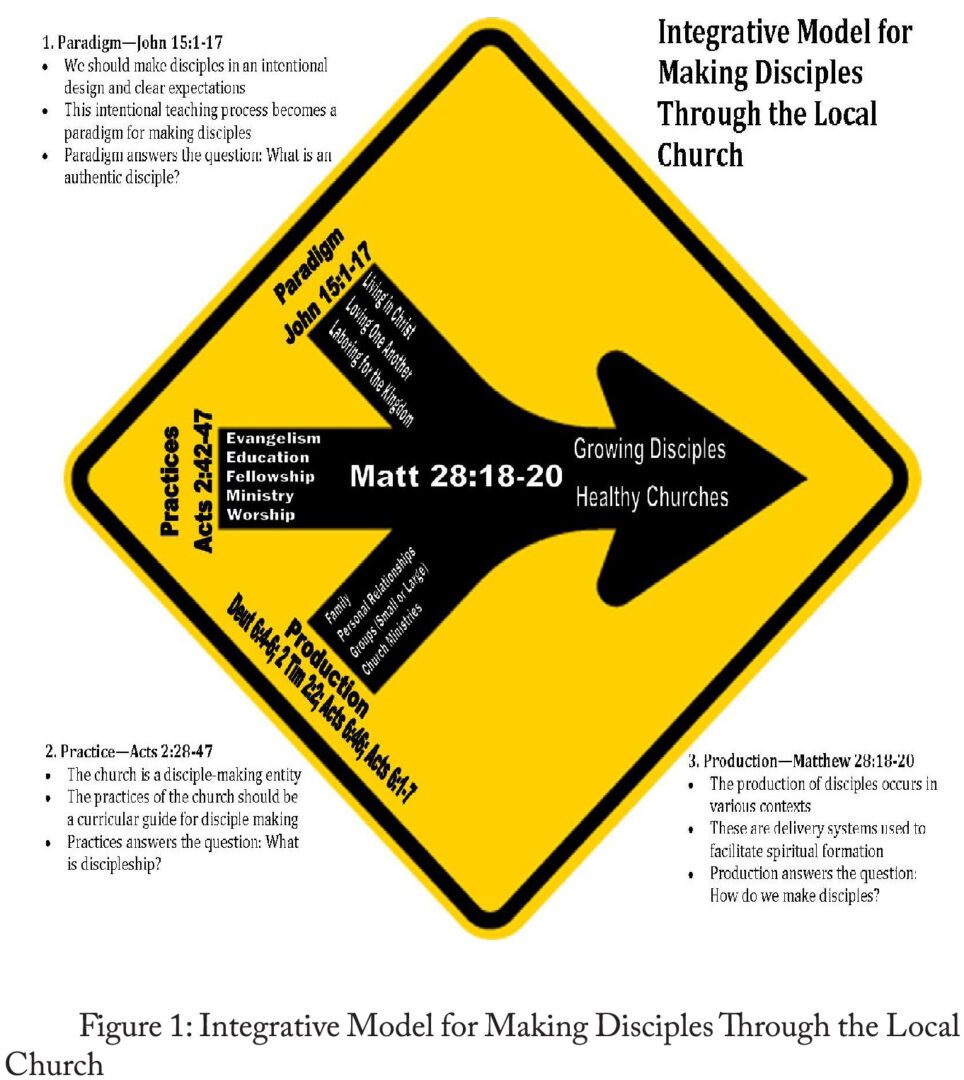

In order to establish once again the primacy of formative discipleship in the local church, I would propose an integrative model for church-based discipleship.26 It is integrative in the sense that it joins together three essential elements in the formation process: a paradigm for the authentic disciple, the practices of the local church, and the production systems used to make disciples in the local church context (see Fig. 1). Within this model there is an assumption that churches would use it as a philosophical and theological guide for decision-making and evaluation.

Paradigm

Creation begins with an end in mind. When God created the world, He knew what He would be creating before He spoke it into existence.27 When Jesus chose his disciples, he already had the final product in mind. He focused his ministry efforts on shaping these disciples into an ever-clearer representation of himself.28 Likewise, the local church should begin the process of making disciples by starting with the end in mind: a paradigm of an authentic disciple, a vision of what it means to be a committed follower of Jesus Christ.

Throughout his ministry, Jesus taught his followers concerning the character and convictions of a true disciple, and Scripture records his teaching on this subject in numerous places within the Gospels.29 However, John 15:1–17 serves as a representative passage that I believe most fully develops the essential attributes of a disciple: living in Christ, loving one another, and laboring for the kingdom.30

Living in Christ. In John 15:4, Jesus calls his disciples to abide in Him. Pentecost explains the meaning of abide as “drawing from something that sustains life.”31 In this case, the disciple’s relationship with Jesus is what maintains spiritual health and vitality. This essential relationship is the first priority of a growing disciple. Jesus states that spiritual formation is dependent upon this sustaining relationship, one in which the disciple receives a constant flow of spiritual nourishment from the divine source. Without this nourishment, the disciple is incapable of any growth and devoid of spiritual power.32

Living in Christ describes the relational priority of the disciple’s life. It is in this relationship that he is formed from the inside out. Disciples develop an abundant life in Christ as they worship—corporately and personally—and as they spend time reading, meditating upon, and memorizing the Word of God. The discipline of prayer enriches the intimacy of the disciple’s relationship with Christ and attunes his heart to the will of the Father. These and other formative disciplines change the inner man and develop Christ-like character within the heart of the disciple. The evidence of growth is the presence of Spirit-produced fruit that characterizes the one who lives in Christ. Authentic disciples cultivate their love for God, though Christ, and then express that deepening love for Him through love for others in the body and by being on mission for Him in the church and in the world.

Loving One Another. A distinctive proof of one’s status as a disciple is love expressed toward others in the body. Twice in John chapter 15, Jesus commands his disciples to love one another.33 This love was not to be based on subjective feelings for one another, but on their mutual identity as members in the body of Christ. Previously, Jesus had demonstrated the extent of his love for them by taking on the role of servant.34 This act of humble service was an object lesson about the love that Jesus desired for his disciples to express towards each other. He would go on to “lay down his life” at the cross for these friends, and thereby fulfill the symbolism of his servant act in John 13. These two expressions of love serve as literal and figurative standards of the way in which Jesus’ disciples should relate to one another. The authentic disciple builds loving relationships within the body of Christ and expresses that love through a willingness to deny self-interest in deference to the needs of fellow disciples.35

In order to develop the type of love that Jesus commanded us to have for one another, disciples must be willing to share in the experience of spiritual community. Implied within the description of the early church is a life of koinonia, through which the disciples shared common expressions of love for other believers, including those in close proximity and those far away.36 Consequently, the paradigm for an authentic disciple must refer to the desire one has to share in the communal life of the body, as well as the love he expresses to other disciples, including unselfish acts of fellowship, devotion, and ministry.

Laboring for the Kingdom. In John 15:16, Jesus explains the purpose of the spiritual fruit that adorns the life of a devoted disciple. Pursuant to the fact that the fruit is associated with a mission—together with an official appointment and a directive to “go”—Jesus sends out those he has chosen to accomplish his kingdom purpose. Their fruit would be evidenced both internally and externally. The presence of the fruit of His Spirit would be the proof of internal transformation and of their relationship with Him.37 Their external fruit—reproducing themselves through evangelism, teaching, and ministry—would offer practical testimony to the outworking of their faith in Christ. Authentic disciples labor for the kingdom through the active and ongoing witness of their faith in Jesus Christ and by using their Spirit-given gifts in service and ministry to His body.

To be a laborer in the kingdom requires that disciples understand their role within the church as full-fledged ministers of the gospel. It is through the church, and with the church, that followers of Christ accomplish the work of the kingdom; each member of the body is responsible for using the aforementioned grace gifts to build up the church in cooperation with other members.38 In addition, every disciple is responsible for living with a missional perspective: seeing every aspect of life as an opportunity to expand the kingdom of God through evangelistic zeal and personal disciple-making.

Practices

In Acts 2:42–47 we find a model that most would agree contains the essential functions of the church. The practices outlined in this passage include evangelism, teaching, fellowship, ministry, and worship.39 While some would use the term discipleship to describe the teaching practice, I would argue, from the biblical perspective outlined earlier in this article, that discipleship is not a function of the church, but is its principal mission.40 The local church is, or should be, a disciple-making entity. It should be through the efforts and ministry of the church—the gathered body of Christ—that disciples come to know Christ and then make Him known.

Discipleship is the process through which we make authentic disciples; the tasks of the church form the curriculum. Each task represents a body of knowledge and praxis. Each task alone is insufficient to shape authentic disciples; however, the tasks in concert provide a synergism that creates a productive environment for discipleship. As the church fulfills each of these tasks, authentic disciples are nurtured and the health of the church is enhanced.41

Evangelism. Evangelism is the starting point for discipleship.42 Churches are called to “share the gospel of Jesus Christ with others through words, deeds, and lifestyle of church members . . . [and] call people to repentance and faith both locally and throughout the world.”43 Evangelism includes the strategy of missions, which is an organized outgrowth of a kingdom perspective on evangelism. Churches should teach about missions, support missions, and provide opportunities for disciples to experience missions locally and internationally.44

The practice of evangelism, as a component of discipleship, also provides a starting point for making authentic disciples. When a person makes a commitment to follow Christ, he begins a lifelong relationship of living in Christ; at the time of conversion, the Holy Spirit indwells the believer with His presence and the potential for greater growth in Christ occurs. The disciple now has the responsibility to identify with Christ in His church through baptism and then to share the gospel with a lost world and make new disciples. Compassion for the lost should grow as his love for Christ and others increases. Evangelism also offers the disciple an opportunity to labor for the kingdom by testifying to others about God’s work in his life.

Worship. “Worship is acknowledging God in experiences that deepen a Christian’s faith and strengthen a Christian’s service. This function is a response to God’s presence in adoration, celebration, and praise; in confession of sin and repentance; and in thanksgiving and service.”45 Worship is experienced in a disciple’s life in three ways: corporate worship, personal worship, and life stewardship. The local church provides corporate worship as the body gathers regularly to proclaim God’s worth, through preaching the Word and celebrating the ordinances of baptism and the Lord’s Supper.46 As an extension of corporate worship, the disciple should practice regular private worship through Scripture reading and meditation, prayer, fasting, and other disciplines. Worship is also the act of stewarding one’s life to God’s honor, including the dedication of time, talents, and finances for His purposes.

Worship is a vital element in the growth and development of the authentic disciple. The act of worship is a personal manifestation of love for Christ and an expression of the living reality of His presence in the lives of His followers.47 The disciple’s love for other believers increases as they encourage one another in worship and express their corporate unity.48 Worship also provides disciples opportunities to labor for the kingdom by using their spiritual gifts and by offering financial gifts that will be used to continue the ongoing kingdom work of the church.49

Teaching. “The church has responsibility to teach, exhort, and encourage, rebuke and discipline one another.”50 The task of teaching disciples in the church occurs on two levels: scripturally and experientially. “Teaching the Bible to believers . . . provides the foundation for making disciples and for nurturing them.”51 The church also provides “experiences that nourish, influence, and develop individuals within the fellowship of a church.” Teaching provides the disciple with a foundation for a biblical worldview through both formal and informal experiences, through both study and application.

Essential characteristics of the authentic disciple are developed through the task of teaching. There is nothing more important to the development of one’s life in Christ than consistent study of and obedience to the Word of God. The Baptist Faith and Message affirms that “all Scripture is a testimony to Christ, who is Himself the focus of divine revelation.”52 The Bible guides our relationship with Him and instructs us in how we are to live out our faith in Him. Similarly, the Bible informs the proper conduct of our relationships with one another. We learn about the meaning of love and its application through scriptural instruction. The Bible also teaches us about our kingdom responsibilities, our ministry gifts, and the work God has planned and prepared for his disciples.

Ministry. The task of ministry is defined as “a loving response in Jesus’ name to the needs” of all persons, and “involves the church in specific actions to meet human needs in the name of Christ.”53 The importance of ministry in the discipleship process cannot be understated; this is the practical expression of the disciple’s obedience to Christ’s commands and an imitation of his example. The New Testament example of church-based ministry accentuates the effectiveness of corporate efforts as well as the role of the church in providing ministry opportunities to growing disciples.54

Ministry is an outgrowth of two of the characteristics of the authentic disciple and an expression of the third. Love for Christ is perfected by the intentional development of one’s life “in” Christ. That love flows into mutual relationships in the body and into the disciple’s relationships with those outside the church. The kingdom labor of ministry is born at the nexus of love for Christ, obedience to His commands, and compassion for people.

Fellowship. The discipline of fellowship is difficult to define because it describes a Spirit-created bond within the body. Disciples cannot “do” fellowship, as one does ministry, evangelism, worship, or learning. Instead, fellowship is a manner of life and attitude in the church; we live “in” fellowship with one another. “Fellowship is the intimate spiritual relationship that Christians share with God and other believers through their relationship with Jesus Christ.”55 This relationship is expressed through corporate and individual actions that maintain the unity that the church experiences as result of their common relationship in Christ. Primary among the expressions of fellowship in Christ is the meaningful celebration of the Lord’s Supper (1 Cor 10:16–17).

Fellowship is established in the disciple’s relationship with Christ. Although growth in Christ nurtures one’s personal desire to live in unity with other disciples, the effect of corporate growth is much more conducive to sustained fellowship. This points to the need for a discipleship process in the local church that emphasizes gathering in varying sizes of relational groups: mentoring relationships, small groups or classes, ministry teams, and congregational assemblies. It is within these settings that disciples learn how to love one another and are offered opportunities to express that love through action.56 These manifestations of fellowship are usually offered in the form of ministry to the church. Authentic disciples labor for the kingdom when they contribute to the health and well-being of the body by maintaining fellowship through their acts of mutual ministry.

Production

The production of disciples in the local church is facilitated through various formats or delivery systems, including the family, personal relationships, small or large groups and church ministries. Each of these formats is biblically-based and provides a context for spiritual growth using different methodologies and distinctive goals. While some would argue concerning the effectiveness of one system over another, I would submit that churches that provide experiences in each of these contexts will create a more comprehensive environment for making disciples. McDonald observes:

Churches that are “in the Spirit” simply spend most of their time working, planning, and praying over relationships. It is their recurring experience that their most cherished goals are met as they help their members . . . enter and sustain a relationship with a spiritual mentor; teach another person the basics of the Christian life; listen for God’s voice in the context of a small group; and step out of their comfort zone in the realm of mission.57

Family. The family was the first classroom for religious instruction ordained by God. He commissioned parents with the responsibility of teaching their children and passing along from one generation to another not only the truth of God’s word, but also an all-encompassing love for Him and desire to serve Him alone.58 Although parents have given over the lion’s share of this responsibility to church leaders, God’s intention has not changed. The family is still the most effective context for evangelism and spiritual development.59 Discipleship through the family includes:

- Equipping parents to disciple their children

- Promoting spiritual growth opportunities in the home

- Strengthening marriage relationships

Home-based discipleship not only targets the efforts of the church where it can be most effective, but it also strengthens relationships in the family and forges a church “partnership” with parents, wherein the ministry of the church serves to support rather than to supply spiritual training for children. However, the emphasis on family discipleship will not be as applicable to single adults, older adults, or childless couples. This emphasizes the need for options and balance in discipleship delivery systems.60

Personal Relationships. The need for personal investment in discipleship is confirmed through scriptural examples including Paul’s relationship with Timothy and Titus, as well as Jesus’ unique relationship with Peter.61 Para-church organizations, such as Campus Crusade for Christ and the Navigators, specialize in these mentoring relationships between mature disciples and new or growing converts.62 The institutional church, perhaps because of the emphasis on programs and gatherings, has often appeared less effective in nurturing these relationships within the local body. The elements of this discipleship format include:

- One-on-one relationships

- Mentoring and coaching

- New or growing converts learning from mature disciples

This format benefits the disciple by providing a context for two people to experience life together, as the new or growing believer receives a significant investment from the disciple maker. In addition, discipleship can be individualized according to the maturity, needs, and capabilities of the disciple. From the disciple-maker’s perspective, personal relationships provide for greater accountability and more accurate assessment of spiritual growth.

Groups. Group experiences constitute the most common process for discipleship in the local church. The purpose of a group will dictate its size and focus. Large group experiences are useful in communicating a large amount of information in a classroom setting, using a presenter with expertise in a particular area. These include conferences, workshops, and Bible study programs. Small group options include Sunday School classes, home groups, accountability groups, gender groups, and special interest groups. The Sunday School class is the most common group model; these groups deliver discipleship through Bible teaching and fellowship experiences.The “university model”—a schedule of specialty courses related to spiritual growth—is another typical group approach that churches use as a part of a discipleship process. These small group strategies, meeting at either the church site or in homes include common elements:

- Shared leadership approach

- Focus on systematic discipleship or targeted learning

- Emphasis on “building community” and accountability

Groups are a pragmatic approach to discipleship because they provide a context for spiritual formation that is routinely efficient. The larger the group becomes, however, the more difficult it is to establish accountability and assess genuine growth. Balancing the need for building relationships with an instructional agenda can also be problematic. Both factors are important in the discipleship process, but one or the other usually receives the greater emphasis. However, groups remain the most common vehicle for discipleship; creating a process that uses a variety of delivery systems will help to mitigate the weaknesses of any singular approach.

Church Ministries. One of my criticisms of a compartmentalized discipleship approach—presenting discipleship as a church program rather than a church process—is that important church ministries are neglected in the evaluation of discipleship strategies. Ministries that play an essential role in spiritual formation include:

- worship services, formed around the proclamation of the Word and the celebration of the ordinances

- deacon ministry

- mission teams

- evangelism programs

- community outreach

Every ministry program of the local church provides growth experiences that should be included an integrative discipleship process. By doing so, discipleship can be delivered through the normal “rhythm” of church life rather than creating new programs. In addition, leaders begin to see the discipleship potential in their ministries and can use that understanding to plan in conjunction with other leaders. As a result, church health improves along with individual growth.

Using the Integrative Model

The integrative model for discipleship in the local church is designed to be descriptive and prescriptive; in other words, the usefulness of the model lies in its ability to serve as an evaluative tool for assessing the current state of discipleship in the local church, as well as its value in planning, improving, and implementing an intentional discipleship process.

The model uses a modified “merging traffic” symbol to illustrate Matthew 28:18–20. The arrow points to the goal of making authentic disciples who are growing in Christlikeness and reproducing themselves. Simultaneously, the same process is improving the health of the local church; healthy churches are composed of growing disciples. Three distinct paths flow towards this goal: a paradigm for the authentic disciple, the practices of the local church, and the contexts used for the production of disciples.

The paradigm path describes the characteristics of a disciple who is developing in an upward relationship of devotion to God through Christ, an inward relationship of love for the body, and an outward relationship of compassion for the lost world. This description includes the markers for assessing the development of disciples in the local church and provides the objectives for discipleship planning.

The path of practices focuses on the fundamental tasks of the local church and describes a healthy, kingdom-focused agenda. The role of these practices in this discipleship model is, first, to acknowledge the importance of the church in making disciples and, second, to provide an outline for comprehensive discipleship. Assessing or planning the content for a discipleship process should take into account the thematic balance inherent in the church practices.

The production path presents a list of options for delivering discipleship through the local church. Although not an exhaustive list, the options represent the most common approaches for making disciples. The purpose of the production path is to emphasize the importance of using a multifaceted approach to content delivery. Disciples are developed in a variety of contexts: learning in classrooms, sharing with fellow disciples, worshipping in the congregation, working on the mission field, serving in ministry, relating to mature role models, and maturing in a family setting.

The integrative aspect of this model begins at the point at which these roads converge. Comprehensive discipleship planning begins with an end in mind. What kind of disciple are we seeking to make? With a paradigm in place, we can address content decisions. How do the practices of the church guide our process for making authentic disciples? With our concept and content established, we can provide a context for growth.

What formats can we use to produce authentic disciples? By asking these questions in conjunction with the principles in this integrative model, church leaders have the tools they may use to maintain a comprehensive discipleship process and reclaim the biblical mandate to make disciples and establish healthy and kingdom-focused churches.

- George Barna, Revolution: Finding Vibrant Faith Beyond the Walls of the Sanctuary

(Carol Stream, IL: Tyndale House, 2005), 64. ↩︎ - Albert Mohler, “A Revolution in the Making?,” February 13, 2006, http://www. crosswalk.com/blogs/mohler/1378183/ (Accessed 25 March 2008). ↩︎

- Barna, Revolution, 48. ↩︎

- Ibid., 13. ↩︎

- Matt 28:18–20; Unless otherwise indicated, all Scripture references are from the Holy Bible, New American Standard Bible (NASB). ↩︎

- Michael J. Wilkins, Following the Master: The Biblical Theology of Discipleship (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1992), 40. ↩︎

- Gary C. Newton, Growing Toward Spiritual Maturity (Wheaton, IL: Evangelical Training Association, 1999), 15. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Wilkins, Following the Master, 41. ↩︎

- Bill Hull, The Complete Book of Discipleship: On Being and Making Followers of Christ

(Colorado Springs: NavPress, 2006), 53–61. ↩︎ - Wilkins, Following the Master, 105–18. ↩︎

- Bill Hull, The Disciple Making Church (Grand Rapids: Fleming H. Revell, 1990), 18.

Luke also uses brothers, Christians, people, and believers to refer to followers of Christ. ↩︎ - John B. Polhill, Acts, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman, 1992), 273. Although the label is used in Acts 11:26 and 26:28, Polhill asserts that its early use outside the church may reflect (1) the establishment of a Christian identity outside Judaism, and (2) a common way that Gentiles would refer to other Gentiles who became Christ followers. ↩︎

- Acts 6:7; 9:26; 11:26; 14:21–22, 26–28; 18:23, 27; 19:1; 21:3–6. ↩︎

- Dietrich Bonhoeffer, The Cost of Discipleship (New York: Touchstone, 1959), 47. ↩︎

- Hull, The Complete Book of Discipleship, 33. ↩︎

- Ibid., 41–44. ↩︎

- Ibid., 35. ↩︎

- American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 4th ed., s.v. “-ship.” http:// dictionary.reference.com/browse/-ship (Accessed 24 March 2008). ↩︎

- Dictionary.com Unabridged, 1.1st ed., s.v. “-ship.”, http://dictionary.referece.com/ browse/-ship/ (Accessed 24 March 2008). ↩︎

- Hull, The Complete Book of Discipleship, 35. ↩︎

- Baptist Faith and Message 2000, Article VI. ↩︎

- Herschel W. Hobbs, The Baptist Faith and Message: Revised Edition (Nashville: LifeWay, 1996), 69. ↩︎

- Greg Ogden, Transforming Discipleship: Making Disciples a Few at a Time (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 2003), 31. ↩︎

- James C. Wilhoit, Spiritual Formation as if the Church Mattered: Growing in Christ through Community (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2008), 15–16. ↩︎

- Wilkins, Following the Master, 346. The author calls for a more “integrative understanding” of discipleship in which process, rather than programs, is the focus. ↩︎

- Gen 1:1 ↩︎

- John 17:26 ↩︎

- Luke 9:62, 14:26–33, John 8:31, 13:35 are a few examples of Jesus’ requirements of his disciples, stated both in negative and positive terms. ↩︎

- Wilkins, Following the Master, 357–58. Although Wilkins does not use these particular phrases, he uses the idea of three marks of a disciple: abiding in Jesus’ word, loving one another, and bearing fruit. I have used these ideas in their relationship to John 15. ↩︎

- J. Dwight Pentecost, Design for Discipleship (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1977),

52. Pentecost uses the examples of plants abiding in the ground, fish abiding in the sea, and birds abiding in the air. These examples illustrate a symbiotic relationship in which a living entity relies upon its environment for life. In the same way, the disciple’s abiding relationship with Christ is that nurturing environment. ↩︎ - John 15:5–8. ↩︎

- John 15:12, 17. ↩︎

- John 13:1–17. ↩︎

- This is the “same love” that Paul describes in Philippians 2:1–11, where he exhorts the disciples to imitate the self-sacrificing attitude of Christ in their relationships with one another. ↩︎

- Paul’s collection for the saints in Jerusalem (Rom 15:26, 1 Cor 16:1–3) was an opportunity for the wider body of Christ to express their love for a sister church. ↩︎

- Gal 5:22–23. ↩︎

- 1 Cor 12:7. ↩︎

- Morlee Maynard, We’re Here for the Churches: The Southern Baptist Convention Entities Working Together (Nashville: LifeWay, 2001) 9–14. Maynard lists the basic functions of the church as worship, evangelism, missions, ministry, discipleship, and fellowship. I am using Maynard’s descriptions of these functions, although I will use a slightly different nomenclature in this article. ↩︎

- Hull agrees: “Discipleship is not just one of the things the church does; it is what the church does.” Hull, Complete Book of Discipleship, 24. Likewise, Wilkins states that “discipleship is the ministry of the church.” Wilkins, Following the Master, 345. ↩︎

- Hull, Disciple Making Church, 64. Authentic spiritual formation, according to Hull, depends on consistently practicing the spirit of the functions outlined in Acts 2:42–47. He presents these practices in the form of five “commitments”: commitment to Scripture, one another, prayer, praise/worship, and outreach. ↩︎

- Harold S. Bender, These Are My People: The Nature of the Church and its Discipleship According to the New Testament (Scottsdale, PA: Herald Press, 1962), 76. Bender cites Acts 14:21 as evidence that making disciples begins with “a response to the preaching of the Gospel.” ↩︎

- Maynard, We’re Here For the Churches, 10. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Rom 12:1–2. ↩︎

- Heb 10:25–26. ↩︎

- 1 Cor 14:26; Ps. 116:17–18. ↩︎

- Maynard, We’re Here For the Churches, 12. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Baptist Faith and Message 2000, Article I. ↩︎

- Maynard, We’re Here For the Churches, 11. ↩︎

- Acts 6:1–7. ↩︎

- Maynard, We’re Here For the Churches, 13. ↩︎

- Glenn McDonald, The Disciple Making Church: From Dry Bones to Spiritual Vitality

(Grand Haven, MI: FaithWalk, 2004), 98. ↩︎ - Ibid., 16. ↩︎

- Deut 6:4–9. ↩︎

- Wilkins, Following the Master, 345. ↩︎

- Ibid. Wilkins believes that both the home and the church have been given the responsibility for the disciple making process. In Matthew 12:46–40, Jesus affirmed the identity of a new “spiritual family” that would become the role of the church. ↩︎

- Matt 16:15–19; John 21:15–17; 2 Tim 1:2–6; Titus 1:4. ↩︎

- Hull, Disciple Making Church, 30–31. According to Hull, these organizations use a “Christocentric” model of disciple making that focuses on the accumulation of knowledge and development of ministry skills in groups of “like-minded, gifted, task-oriented people.” He recommends a “churchocentric” approach and recognizes a broader mission and “a multiplicity of beliefs about church priorities.” ↩︎