Liberty of Conscience

Southwestern Journal of Theology

Volume 67, No. 1 - Fall 2024

Editor: Malcolm B. Yarnell III

B. R. White, Isaac Backus, and Baptist History

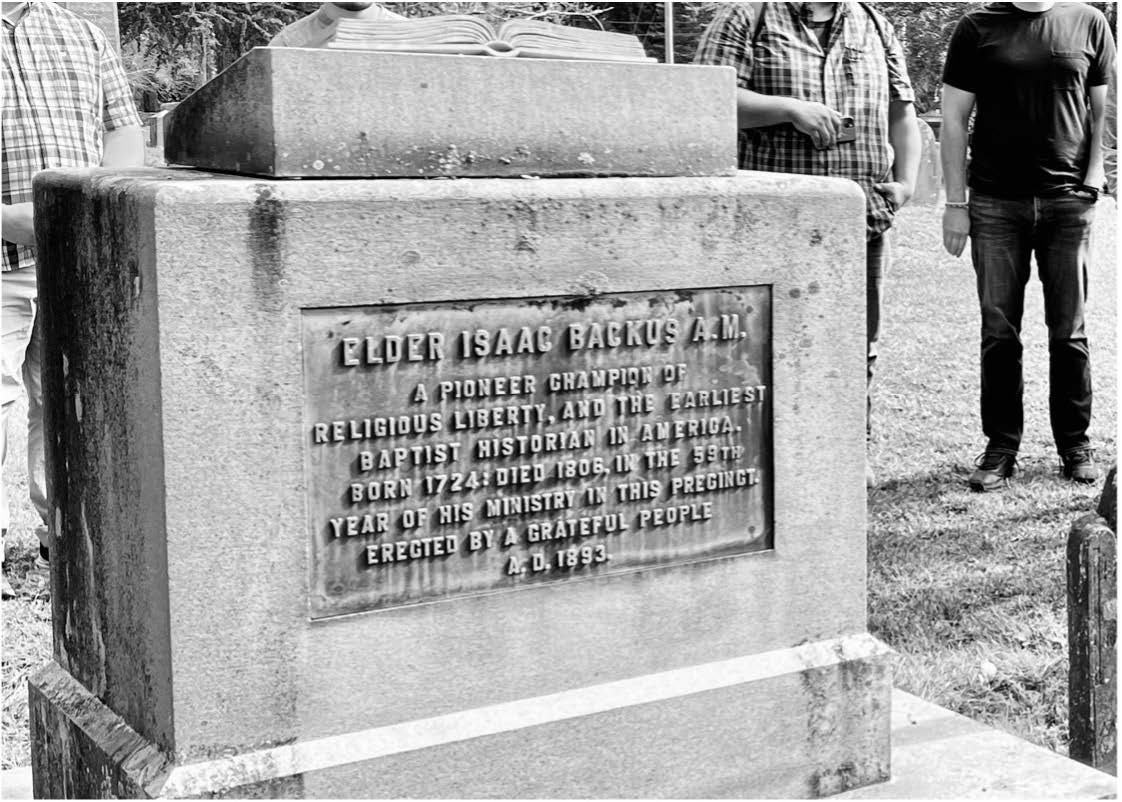

Perhaps there is no historical artifact more biased than the tombstone. The inscriptions used, though brief and, likely, because of the required brevity, tell only the best about a life, or, at least, shed the best light possible. The grave of Isaac Backus (1724-1806), erected years after his death to memorialize him, summarizes his life, in part, as “a pioneer champion of religious liberty.” As this year marks the three-hundredth anniversary of his birth, I aim to ask whether this perspective, though biased, is accurate. And I’d like to think I do so in good company.

At an address given at the annual meeting of the Historical Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention in April 1969, the British Baptist historian, Barrington Raymond White (1934-2016), started his opening address by asking the question, “Why bother with history?” Therein, he sought to raise questions about the study of Baptist history in comparison to other types of history.1 Positing that Baptist historians should “ask questions about the bias and interests of the Baptist Historians who are our forerunners,” White noted the errors he encountered while researching the source work of the first English Baptist historian, Thomas Crosby (1683- 1752). Questioning why earlier Baptist historians used the sources they used, told the stories they told or did not tell, is the type of bias analysis, White relayed, “where considerable fresh work is needed.”2 Indeed, White shared, this is how he arrived at the subject for his concluding address to the Historical Commission. Just as he analyzed the biases of the first English Baptist historian, he intended to do the same with the first Baptist historian in America, Isaac Backus.3

In that address, “Isaac Backus and Baptist History,” White, with some irony, gave a sympathetic and biased portrayal of Backus as, himself, a sympathetic and biased Baptist historian.4 Isaac Backus wrote his four volume A History of New England with Particular Reference to the … Baptists throughout the course of his public ministry (1777-1804) and during the time at which America formed as a nation following revolution. As he recounted the events that led to the new nation’s freedom, Backus also wrote with the survival and freedom of Baptist churches in mind. White summarized, “Backus was no armchair historian: his was crusading history, passionate history, a record of past events made by a man whose eyes were firmly fixed on the necessity of setting that record straight for the sake of the future.”5 As we will note, Backus’s History of New England served to complement Backus’s larger cultural engagement project while upholding the legitimate existence of Baptist churches. Indeed, this forward-looking approach of America’s first Baptist historian, White concluded, “helped to give the denomination, which had been virtually reborn through the Great Awakening, a sense of corporate identity.”6

Therefore, if B. R. White concluded that Backus was a biased, but faithful Baptist historian, what do we make of the claim that Backus was a “pioneer champion of religious liberty?” As this session marks the three-hundredth anniversary of Backus’s birth, it is easy to survey and show how Baptist historians have, for 300 years, concurred with this assessment. In that time, Backus is universally regarded by Baptist historians, in biographies and textbooks, for the formative role he played in the disestablishment of state religion.7 However, his name does not appear in American history textbooks that are not Baptist or Christian.8 Given that comparison, are Baptist historians, who laud him as a pioneer champion of religious liberty, biased toward one of their forerunners or accurate in their assessment, or both? Rather than survey the history of historians, my aim is to return to the source to ascertain from Backus’s own writings the degree to which he was a pioneer champion of religious liberty. Given the constraints of this essay, what follows is a brief assessment of Backus in eight works.

A Brief Assessment of Eight Works on Religious Liberty

A DISCOURSE SHOWING THE NATURE AND NECESSITY OF AN INTERNAL CALL TO PREACH THE EVERLASTING GOSPEL, 1754

Serving as pastor of new Congregational church since 1748, Backus and his church wrestled with their practice of infant baptism. Since his conversion came due to the influence of the Great Awakening, Backus grew in his convictions that internally churches should be pure in their membership in order to ensure that their clergy were converted and the gospel message proclaimed in faithfulness. Thus, the baptized infants as members prior to their conversion only added to the impurity. Externally, Backus maintained that only God should determine who should be called as ministers of the church, not ruling councils nor the state. His congregationalism extended toward the resistance, in Massachusetts, to pay taxes to the established church, an action for which his mother and brother paid with a prison sentence.

Thus, in his work, Internal Call, written at the end of 1753, Backus, now a Baptist, writes largely to defend his understanding of a biblical call to ministry as well as to warn against the dangers of unconverted ministers. In this passage, Backus is responding to a query and upholds that it is the role of the church alone to recognize the internal call of their minister. This idea of a sola ecclesia, if you will, is rooted, for Backus, in the Reformation and is carried forward through the likes of the Separatist John Robinson (1575-1625) and the arguments of Jonathan Edwards (1703-1758). As O’Brien notes, Backus’s “arguments became sharper and clearer over time” as they developed into his advocacy for religious liberty, but we can see here how his understanding of the doctrine is rooted in his understanding of the church.9 Here are Backus’s thoughts as of 1754:

This text [2 Tim 2:2] proves clearly, that Gospel-Ministers should be ordained and publicly set apart in the Church, and I have no where denied it. … They are called of God and made faithful in his work before they can be rightly received and ordained officers in his Church. … A man’s being internally called of God is one thing, and his being openly received and set apart in the Church is quite another. And I defy all men under Heaven to prove from Scripture that God has any more left it in the hands of any mortal men whatsoever to say who shall be his ministers and who not than he has to say who shall be his children and who not. The argument that is raised from the Scriptures being complete is as good in one case as the other. For it is no more recorded in the Bible that this or that man is, or shall be, called to preach the Gospel. We have plain marks given us whereby we may know them that the Lord has called into the kingdom of his grace, and so we have also rules whereby we may know them that He has called to be his messengers.10

A FISH CAUGHT IN HIS OWN NET, 1768

As Backus’s views continued to develop, he and others formed a Baptist church in Middleborough in 1756. Pastoring in the 1750s and 1760s brought criticism also from the established church due to the fact that following the Awakening, many people were leaving those churches to join the Separates. One frequent interlocutor that appears in a few of Backus’s writings in this era is Joseph Fish (1706-1781). The pastor of the Congregational church in Stonington, Connecticut, since 1732, Fish published a volume of nine sermons on what he considered the errors of the Separates, like Backus. In September 1767, Backus noted that many of his “friends desired me to answer,” and in 1768, he did with the clever title A Fish Caught in His Own Net.11 Therein, he debated Fish’s understanding of “Standing churches” who exist due to their “union declared with the civil authority.” In this line of thinking the civil authorities preserve the churches and restrain them from acting upon their own preferences without consulting other churches in order to uphold “the order and rule of the Gospel.”12 This selection shows Backus’s thinking about religious liberty in 1768, and we can see why William McLoughlin said, “here Backus finally came to grips both theoretically and pragmatically with the definition of his basic principles for a doctrine of separation of church and state.”13

[A]s civil rulers ought to be men fearing God, and hating covetousness, and to be terrors to evil doers, and a praise to them who do well; and as ministers ought to pray for their rulers, and to teach the people to be subject to them; so there may and ought to be a sweet harmony between them; yet as there is a great difference between the nature of their work, they ought never to have such union together as was described above.

1. For, The Holy Ghost calls the orders and laws of civil states ordinances of man, 1 Pet. ii, 13. But all the rules and orders of divine worship are ordinances of God, and it defiles the earth under its inhabitants when these laws are transgressed and ordinances changed, Isai. xxiv, 5. …

2. The civil magistrate’s work is to promote order and peace among men in their moral behavior towards each other so that every person among all denominations who doth that which is good may have praise of the same, and that all contrary behavior may be restrained or forcibly punished. And as all sorts of men are members of civil society and partake of the benefits of such government therefore they ought to be subject and pay tribute to rulers, Rom. xiii, 1-6. But the work of Gospel Ministers is to labor to open men’s eyes and to turn them from darkness unto light, and from the power of Satan unto God, Acts xxvi, 18. …

3. Another difference between civil and ecclesiastical government is that civil states, if large, have various degrees of offices one above another who receive their authority through many hands, down from the head and that often, more according to estate or favor than of merit. But ’tis the reserve in Christ’s kingdom; he forbid the first notions of this in his disciples and expressly told them that it should not be so among them as it was in earthly states, Mark x, 43; Luke xxii, 26. An obvious reason of this difference is that an earthly king cannot in person see to but little that is done in his kingdom and therefore must trust others to manage affairs for him in his absence; but Zion’s King is present everywhere and sees to all that is done and tells every church, I know thy works, and he takes care that the faithful are supported and rewarded and that the unfaithful are corrected or punished.14

A SEASONABLE PLEA FOR LIBERTY OF CONSCIENCE, 1770

In the summer of 1770, Isaac Backus was preaching in the town of Berwick, Maine, when he encountered the experience of a couple in the Congregational church who were excommunicated in recent years following their joining a Baptist church. As the town continued to require the Baptist couple to pay taxes to fund the Congregational church, Backus wrote A Seasonable Plea to take up their cause.15 This action is representative of Backus’s beginning to advocate for other Baptists beyond his own congregation, a ministry of public service that will continue for the rest of his life.16 At the start of A Seasonable Plea, Backus explains that, “what had the greatest weight in my mind was the consideration that many who are filling the nation with the cry of liberty, and against oppressors, are at the same time themselves violating that dearest of all rights, liberty of conscience.”17

At issue was the concept of “liberty of conscience,” about which Backus and the leaders of the Congregational church had differing definitions. The leaders of the church in Berwick stated that, “Liberty of conscience we claim ourselves and allow others, as a darling point, and therefore must not be forced to anything contrary to our consciences.”18 Thus, Backus encountered a church not opposed to religious liberty, but rather liberty as defined by the church’s conscience, not the consciences of those who were dissenting based on their understanding of Scripture. To this Backus asked, “Why truly their members are forced either to believe as the church believes, or be dealt with as public offenders! … If it is only the church that is to judge, then where is their allowance of liberty to others as a darling point!”19

Backus continued to bolster his plea with an appeal to the shared cause of Revolution. In this quotation from his work, we see Backus making his case on a theme to which he will return as he continued to advocate for Baptists in the public square.20

Some would accuse us of being enemies to our country because we move in these things now. Though if regard to our country had not prevailed above our private interests, possibly the court of Great-Britain would have heard our complaints before this time. However, let our accusers turn the tables. Let them hear their oppressors exclaiming from year to year against being taxed without their own consent, and against the scheme of imposing episcopacy upon them. While the same persons impose cruelly upon their neighbors, and force large sums from them to uphold a worship which they conscientiously dissent from, and then see if they will sit still until their oppressors have got fully established in their power, before they seek deliverance from their yoke, for this is truly our case.21

A CIRCULAR LETTER TO THE CHURCHES OF THE WARREN BAPTIST ASSOCIATION, 1773

During the 1760s Baptist churches in New England worked together to form a more cohesive presence as an ecclesial minority, and Backus emerged as a clear leader. Working with pastor James Manning (1738-1791), Backus helped to form the College of Rhode Island where Manning would serve as president. Following the increased strength of the Philadelphia Baptist Association of churches, Manning also led in the formation of the Warren Baptist Association (1767), an advisory council for churches.22 This new Association sought to advocate for Baptist churches and religious liberty in view of the civil authorities, but from the onset, claimed no superiority or infallibility over the churches who “profess the Scriptures to be the only rule of faith and practice in religious matters.”23

By 1769 the Warren Baptist Association formed a Grievance Committee to receive accounts of persecution by Baptists and to advance their cause and the cause of religious liberty. As one of the founding members of that committee, Backus used this platform as a chief means by which he engaged establishment oppression.24 This selection gives an example of one of the circular letters Backus sent to Baptist churches in May 1773.

[W]hen we received accounts that several of our friends at Mendon have lately had their goods forcibly taken from them, for ministerial rates, and that three more of them at Chelmsford, [were] carried prisoners to Concord jail; so that liberty of conscience, the greatest and most important article of all liberty, is evidently not allowed, as it ought to be in this country, not even by the very men who are now making loud complaints of encroachments upon their own liberties. And as it appears to us clear that the root of all these difficulties, … is civil rulers assuming a power to make any laws to govern ecclesiastical affairs, or to use any force to support ministers; therefore, these are to desire you to consider whether it is not our duty to strike so directly at this root, as to refuse any conformity to their laws about such affairs, even so much as giving any certificates to their assessors. We are fully persuaded that if we were all united in bearing what others of our friends might, for a little while, suffer on this account, a less sum than has already been expended with lawyers and courts, on such accounts, would carry us through the trial, and, if we should be enabled to treat our oppressors with a Christian temper, would make straining upon others, under pretence of supporting religion, appear so odious that they could not get along with it. We desire you would consider of these matters, and send in your mind to the assembly of our churches.25

AN APPEAL TO THE PUBLIC FOR RELIGIOUS LIBERTY, 1773

Following the responses received to Backus’s circular letter and the work of the Grievance Committee, later that year the Association voted to publish a document Backus wrote as an appeal to the public that Baptists should not accept the exemption certificates offered to them by the state. These certificates allowed for Baptists to avoid paying taxes to support the established church, but the issue for the Warren Association remained that by accepting them they were conceding that the state had the power to grant them, and what they wanted was absolute and total freedom from this kind of state power over religion.26 Thus, Backus’s document called for the Baptists to refuse the certificates. While this would, no doubt, bring persecution, Backus believed it would make their case to the public and, thereby, have a lasting effect.27

To aid in this strategy, the Warren Association sent Backus and Manning, along with copies of An Appeal, to the 1774 Continental Congress meeting in Philadelphia. Samuel and John Adams, elected by Massachusetts to represent their state, were not convinced by their argument for disestablishment, citing that establishment in Massachusetts was “slender” and that the Baptists had “no cause to complain.”28 Nonetheless, Backus persisted, and while not gaining much ground in 1774, his efforts would persevere. In this selection, Backus articulates his argument for religious liberty.

The great importance of a general union through this country in order to the preservation of our liberties has often been pleaded for with propriety, but how can such a union be expected so long as that dearest of all rights, equal liberty of conscience, is not allowed? Yea, how can any reasonably expect that He who has the hearts of kings in his hand will turn the heart of our earthly sovereign to hear the pleas for liberty of those who will not hear the cries of their fellow subjects under their oppression? … You have lately been accused with being disorderly and rebellious by men in power who profess a great regard for order and the public good. And why don’t you believe them and rest easy under their administrations? You tell us you cannot because you are taxed where you are not represented. And is it not really so with us? …

Thus we have laid before the public a brief view of our sentiments concerning liberty of conscience and a little sketch of our sufferings on that account. If any can show us that we have made any mistakes either about principles or facts, we should lie open to conviction. But we hope none will violate that forecited article of faith so much as to require us to yield a blind obedience to them or to expect that spoiling of goods or imprisonment can move us to betray the cause of true liberty.29

GOVERNMENT AND LIBERTY DESCRIBED, 1778

After the country declared independence in 1776, Baptists, as Todd notes, “believed that the Revolution in America would give way to an actual reformation of the church, a refining of any traces of civil authority from the kingdom of God.”30 For Baptists in Massachusetts, their hope centered on a new state constitution. Yet the version that appeared in 1778 made no mention of religious liberty. In part, no change followed the standing assumption that, in New England, the church and state achieved separation with the removal of Anglican rule even though all citizens still paid tax to support established churches.

When that constitution failed to achieve ratification, Backus and the Warren Association published Government and Liberty Described to stir up support for the inclusion of complete freedom of religion. In this selection, Backus elevates his argument that Baptists are paying a tax without representation and makes, what McLoughlin calls, “the best piece that Backus ever wrote as a lobbyist for the Baptists.”31

1. Consider what our civil liberties will be if these men can have their wills. I need not inform you that all America are in areas against being taxed where they are not represented. But is it not more certain that we are not represented in the British Parliament than it is, that our civil rulers are not our representatives in religious affairs. Yet ministers have long prevailed with them to impose religious taxes entirely out of their jurisdiction. And they have now been defied to preserve order in the state if they should drop that practice. …

2. How can liberty of conscience be rightly enjoyed till this inquiry is removed? … They often declare that they allow us liberty of conscience and also complain of injury if we recite the former and latter acts of their part to prove the contrary. Just so [they say], “Should a general tax be laid upon the country and thereby a sum be raised sufficient for that purpose, I believe such a tax would not amount to more than four pence in one hundred pounds, and this would be no mighty hardship upon the country. …” [T]here lies the difficulty. It is not the pence but the power that alarms us. And since the legislature of this State passed an act no longer ago than last September to continue a tax of four pence a year upon the Baptists in every parish where they live as an acknowledgment of the power that they have long assumed over us in religious affairs … how can we be blamed for refusing to pay that acknowledgment; especially when it is considered that it is evident that God never allowed any civil state upon earth to impose religious taxes?32

POLICY AS WELL AS HONESTY, 1779

Backus’s Government and Liberty Described instigated a high-profile debate via the exchange of newspaper responses that served to advance the cause of the Baptists and keep the liberty of conscience a topic of conversation.33 When new delegates were elected to write another version of the Massachusetts constitution in 1779, Backus, acting on behalf of Baptists and in an effort to influence the delegates, published another tract challenging religious taxation and reasserting many of his arguments from his newspaper articles.34 In this selection from Policy As Well As Honesty Forbids the Use of Secular Force in Religious Affairs, Backus displayed both his rhetorical skills.

As no man can have a right to judge for others in soul affairs, so they never could convey such a right to their representatives. Therefore all the taxes to support religious worship and judgments in such cases that have been among us were a taxing of us where we were not represented and imposing judges upon us who were interested against us. … Although the comfortable support of religious ministers is most expressly required both in the Old and New Testaments, yet the use of force to collect it, and against those who have testified against that practice, has produced such effects in all ages as none have been willing to own. But the Judge cannot be deceived by their deceitful coverings and tells us all what will become of those who allow of such deeds against the plain light to the contrary.35

Rulers, ministers, and people have now a fair opportunity given to them to turn from and quit themselves of those evils, and I cannot but hope they will improve it. … Therefore we have joined as heartily in the general defense of our country as any denomination therein, and I have a better opinion of my countrymen than to think the majority of them will now agree to deny us liberty of conscience.36

A DECLARATION OF THE RIGHTS, 1779

A fellow Baptist pastor and a friend of Backus, Noah Alden, served as one of the delegates to the Massachusetts Constitutional Convention in 1779. Prior to his joining the convention, he wrote to ask Backus for a “Bill of Rights” that outline the “natural civil and religious rights of the people.”37 Backus used the 1776 Bill of Rights included in the Virginia constitution as a foundation but amended it to fit the New England circumstances and context.38 In the short term, Backus’s optimistic efforts as an agent of the Baptists advocating since 1778 for the inclusion of religious liberty and, now also, a Bill of Rights failed. The 1780 Massachusetts constitution included neither and, what is more, used Backus’s efforts dating back to his 1774 visit with the Adamses in Philadelphia to malign him, question the truthfulness of his work, and accuse Baptists of disloyalty to the Patriot cause.39 In the long term, Backus’s labors proved influential and led to disestablishment in Massachusetts. This selection shows Backus’s mature thought on religious liberty.

1. All men are born equally free and independent, and have certain natural, inherent and unalienable rights, among high are the enjoying and defending life and liberty, acquiring, possessing, and protecting property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.

2. As God is the only worthy object of all religious worship, and nothing can be true religion but a voluntary obedience until his revealed will, of which each rational soul has an equal right to judge for itself, every person has an unalienable right to act in all religious affairs according to the full persuasion of his own mind, where others are not injured thereby. And civil rulers … that their power ought to be extorted to protect all persons and societies, within their jurisdiction from being injured or interrupted in the free enjoyment of this right, under any pretense whatsoever.40

Following the adoption of the state constitution in Massachusetts, Backus continued to serve the Warren Baptist Association to take up the defense of Baptists in hopes of seeing disestablishment in his lifetime. Meanwhile, the nation as a whole considered a new constitution. As Massachusetts elected delegates to consider whether their state should ratify this constitution, Backus agreed to serve and used his influence to support ratification. For Backus, again, saw a window of hope for religious liberty. Indeed, when given the opportunity to speak to his delegate peers in Massachusetts, he said he saw the constitution as a door “now opened, for the establishment of righteous government, and for the securing of equal liberty, as never was before opened to any people upon earth.”41 Following the full ratification by all the states in 1791, the United States Constitution included a Bill of Rights with a first amendment that established the free exercise of religion at the national level.

A Pioneer Champion?

Just as B. R. White concluded that Backus’s History of New England served to galvanize a denomination seeking its freedom from state religion, this brief assessment of eight of his works on religious liberty reveals Backus’s influence on more than just laying a foundation for state and national debate. In the decades following Backus’s death, both Connecticut and his own Massachusetts would disestablish their state churches joining every other state in the nation. In his writings, letters, and his advocacy in meetings on behalf of the Warren Association, he, indeed, was a pioneer of religious liberty. But, as a pastor and one who represented pastors, it is right to stress that Backus was “a” pioneer, one among several leaders, and one on behalf of many churches.

As his efforts contributed to, first, the ratification of the Constitution, and then to the First Amendment and the Bill of Rights, it is right to see Backus also as a champion of religious liberty. While not recognized today in standard U. S. history textbooks, his influence on the people and events mentioned in those textbooks as they recount the new nation’s commitment to religious freedom is clear. Given Backus was a Baptist pastor who achieved this influence, is it biased for Baptist historians to laud him as a pioneer champion of religious liberty when most historians fail to mention him? Perhaps it is, but as B. R. White instructed, the evidence of such bias does not mean it is false. Indeed, this kind of fair, yet “passionate history” (to use White’s description) may yet still serve to promote the value of Backus to students of history regardless of whether they know (or care) that he was a Baptist. Even more, recognizing Backus as a person worth retrieving from history could also serve to perpetuate the Backus ideals, whether or not Backus is mentioned by name, so that this nation might persist and celebrate true freedom of religion for its citizens for centuries to come.

A Grateful People

When one travels to Middleborough, Massachusetts, today, it is easy to imagine what it looked like 300 years ago. While nearby are several major New England metro areas, Middleborough is not exactly on the way to any of them and maintains the rural roadways and markers that Backus would still find familiar. Thus, in recent months when traveling in search of Backus’s grave with three vans full of graduate students, just in case we could not find it, I held on to alternative plans for lecturing in any field “near where Backus lived and died” instead of the grave itself. While Backus’s grave is hard to miss when you are in the right place, it is not documented well in New England guidebooks.

On the western edge of the Titicut Parish Cemetery, next to the North Congregationalist Church, where Backus pastored before he became a Baptist, Backus’s grave sits near the parking lot. The grave is designed as a stone pulpit, with a large open Bible on top. On the side, a plaque, now green with age memorializes Backus, as we have discussed, as “a pioneer champion of religious liberty, and the earliest Baptist historian in America.” Further, it notes that the monument was “erected by a grateful people.” Who were these grateful people? While Backus’s first grave marker was placed at his death, nearly 70 years later, when the Old Colony Baptist Association had their anniversary meeting in Middleborough, they concluded that the small, original marker was not a fitting memorial.42 They returned almost twenty years after their meeting, and almost a century after Backus’s passing, to dedicate the large pulpit marker that remains today to express their gratitude for Backus’s legacy.43 Regardless of whether or not Backus’s name appears in standard U.S. history textbooks today, the fact that a century after his death, Baptists saw fit to reset his grave as an expression of gratitude for his life and ministry, conveys something significant about his lasting value.

We did find Backus’s grave on that trip with the graduate students. As I think of that group gathered around to listen to the stories of Backus and the struggle for religious liberty, it occurs to me that many heard then of Backus, a forefather to whom they were indebted, for the first time. Yet, I think that might be a picture of what Backus and his Baptist peers intended for this country—the idea that for centuries to come, new generations would grow up with widespread religious freedom to the degree that they could not imagine the world in any other way. Those eighteenth-century forerunners would, no doubt, be delighted to know that these students lived with religious freedom much like a young fish lives in an ocean of water—it had not occurred to them to think before of what life would be like without it, and much less, what it cost to secure it. The freedom of worship citizens in this country enjoy—a freedom of religion that comes without having to pay taxes toward an established church or fear of imprisonment, is a remarkable freedom. Therefore, during this year that marks the three-hundredth anniversary of the birth of Isaac Backus, may studies like this propel us to be the kind of “passionate historians” that B. R. White identified so that future generations might continue to learn of and appreciate Backus and his pioneering spirit, so that they, too, will mark themselves also as “a grateful people,” equipped to do their part to ensure that religious liberty remains a remarkable freedom for future generations and for the glory of God.

Photo: Isaac Backus grave, Titicut Parish Cemetery, Middleborough, Massachusetts © Jason G. Duesing (2023)

- B. R. White, “Why Bother with History?” Baptist History & Heritage 4:2 (July 1969): 77-88. White’s original address was titled, “Why Bother about History?” See “Annual Meeting Sound Recording,” Southern Baptist Historical Society (1969 April 23-25), Southern Baptist Historical Library and Archives [SBHLA], Nashville, Tennessee. ↩︎

- White, “Why Bother with History?” 80-81. ↩︎

- White, “Why Bother with History?” 80n6. ↩︎

- B. R. White, “Isaac Backus and Baptist History,” Baptist History & Heritage 5:1 (Jan 1970): 13-23. White’s original address was titled, “Isaac Backus, Classic Baptist Historian,” and served as the seventh and final session of the annual meeting. See “Annual Meeting Sound Recording,” [SBHLA]. ↩︎

- White, “Isaac Backus and Baptist History,” 14. White also notes that Backus’s work “was immeasurably superior to Crosby’s.” White, “Isaac Backus and Baptist History,” 15. ↩︎

- White, “Isaac Backus and Baptist History,” 23. ↩︎

- Representative examples include Alvah Hovey, A Memoir of the Life and Times of the Rev. Isaac Backus (1859), https://archive.org/details/memoiroflifetime01hove/page/n5/mode/2up; A. H. Newman, A History of Baptist Churches in the United States (1894); T. B. Maston, Isaac Backus: Pioneer of Religious Liberty (1962); William G. McLoughlin, Isaac Backus and the American Pietistic Tradition (1967); Stanley J. Grenz, Isaac Backus—Puritan and Baptist: His Place in History, His Thought, and Their Implications for Modern Baptist Theology (1983); H. Leon McBeth, The Baptist Heritage (1987); James Leo Garrett, Jr., Baptist Theology (2009); Nathan A. Finn, Anthony Chute, and Michael A. G. Haykin, The Baptist Story (2015); Thomas S. Kidd and Barry Hankins, Baptists in America (2015); Brandon J. O’Brien’s two works, “The Edwardsean Isaac Backus: The Significance of Jonathan Edwards in Backus’s Theology, History, and Defense of Religious Liberty” (PhD diss., 2013) and Demanding Liberty: An Untold Story of American Religious Freedom (2018); and Matthew W. Thomas, “Snares on Every Hand: Isaac Backus’s Theology of Liberty” (PhD diss., 2022). ↩︎

- A search of several of the textbooks that meet the College Board’s Advanced Placement curricular requirements of AP US history reveals no mention of Isaac Backus. The related name mentioned with regularity is Roger Williams. See “Example Textbook List,” https://apcentral.collegeboard.org/courses/ap-united-states-history/course-audit. ↩︎

- Brandon J. O’Brien, “Isaac Backus,” in Baptist Political Theology, ed. Thomas S. Kidd, Paul D. Miller, and Andrew T. Walker (Nashville: B&H Academic, 2023), 183. See also Thomas, “Snares on Every Hand.” ↩︎

- Isaac Backus, A Discourse Showing the Nature and Necessity of an Internal Call to Preach the Everlasting Gospel (Boston, 1754) in Issac Backus on Church, State, and Calvinism: Pamphlets 1754-1789, ed. William G. McLoughlin (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1968), 100; hereafter abbreviated Pamphlets. ↩︎

- Isaac Backus, The Diary of Isaac Backus, ed. William G. McLoughlin (Providence, RI: Brown University Press, 1979), 2:672. The debates with Fish would continue throughout the 1770s. ↩︎

- Isaac Backus, A Fish Caught in His Own Net, (Boston, 1768), in Pamphlets, 187-189. ↩︎

- William G. McLoughlin, Pamphlets, 169. While not the primary focus, Backus also addressed the matter of slavery in this era in A Fish Caught in His Own Net. Backus critiques the Anglican Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts before whom the Bishop of Gloucester preached a sermon decrying dissenters like Backus as fanatics and advocating for the established church, thus limiting religious freedom. The bishop acknowledged that “the infamous traffic of slaves directly infringes both divine and human law,” yet he did not call for the Society to “set all these slaves at liberty as fast as they could.” Instead, Backus notes the inconsistency of those whose mission is to take the gospel to the heathen, yet “they have a great a hand in the slave trade as any.” Backus, A Fish Caught, in Pamphlets, 176-178. This would appear to put Backus, as a white Baptist, further ahead than most in this era who “spoke reverentially of the Revolution’s significance for universal liberty, but they avoided the Revolution’s (or the gospel’s) implications for slavery.” Kidd and Hankins, Baptists in America, 99. That said, as Obbie Tyler Todd notes, despite his statements, Backus and his Baptist peers likely were “much more concerned with their own quest for liberty” than advocating for abolitionism. Obbie Tyler Todd, Let Men Be Free: Baptist Politics in the Early United States, 1776-1835 (Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications, 2022), 103. Todd does note, 106, that in 1788 Backus, in a speech to the Massachusetts delegates considering the ratification of the national constitution, does express hope that one day slavery in the new nation will come to an end, but does not advocate for the inclusion of abolition in the constitution. Backus, Diary, 3:1220. ↩︎

- Backus, A Fish Caught, in Pamphlets, 190-195. ↩︎

- Backus, Diary, 2:764. ↩︎

- O’Brien notes that it “is helpful to think of Backus’s work in two major phases: (1) from 1754 to 1770, during which time Backus wrote almost exclusively for local ecclesiastical audiences and (2) from 1771 to 1805, during which time his work took on more public and sometimes national dimensions.” Brandon J. O’Brien, “Isaac Backus,” in Baptist Political Theology, ed. Thomas S. Kidd, Paul D. Miller, and Andrew T. Walker (Brentwood, TN: B&H Academic, 2023), 182. ↩︎

- Isaac Backus, A Seasonable Plea for Liberty of Conscience (Boston, 1770), 3. ↩︎

- Backus, A Seasonable Plea, 4. ↩︎

- Backus, A Seasonable Plea, 5. ↩︎

- For more on the ecclesiological implications of A Seasonable Plea, see O’Brien, “The Edwardsean Isaac Backus,” 101-108. ↩︎

- Backus, A Seasonable Plea, 14. ↩︎

- Kidd and Hankins, Baptists in America, 42-43. See also Isaac Backus, A History of New England (1784; repr., Newton, MA: Backus Historical Society, 1871) 2:154-155. ↩︎

- The Sentiments and Plan of the Warren Association (Germantown, 1769). ↩︎

- Backus would serve as the leader of this committee for ten years starting in 1772. ↩︎

- Isaac Backus, “Circular Letter,” May 5, 1773, in Hovey, Memoir of Backus, 188-190. ↩︎

- Backus records, “It is absolutely a point of conscience with me; for I cannot give in the certificates they require, without implicitly acknowledging that power in man which I believe belongs only to God.” Backus, Diary, 2:917. ↩︎

- For further analysis of this strategy, see O’Brien, “The Edwardsean Isaac Backus,” 110. ↩︎

- Backus, Diary 2:916-917. Backus also recorded that John Adams said, “We might as well expect a change in the solar system, as to expect they would give up their establishment.” ↩︎

- Isaac Backus, An Appeal to the Public (Boston, 1773), in Pamphlets, 338-339, 342. ↩︎

- Todd, Let Men Be Free, 27. ↩︎

- McLoughlin, Pamphlets, 346-347. ↩︎

- Isaac Backus, Government and Liberty Described (Boston, 1778), in Pamphlets, 357-359. ↩︎

- McLoughlin, Pamphlets, 368. ↩︎

- Backus, Diary, 2:1025. ↩︎

- See Matthew 23:29-33 and Luke 11:46-52. ↩︎

- Isaac Backus, Policy as Well as Honesty (Boston, 1779), in Pamphlets, 381-383. ↩︎

- Noah Alden to Isaac Backus, August 8, 1779, in Pamphlets, 487. ↩︎

- Backus, Diary 3:1605. ↩︎

- O’Brien, Demanding Liberty, 148-149; Backus, Diary 3:1611-1612. ↩︎

- Isaac Backus, A Declaration of the Rights of the Inhabitants of the State of Massachusetts-Bay, in New-England (n.p., 1779), in Pamphlets, 487-488. ↩︎

- Backus, Diary 3:1220. ↩︎

- The original marker was removed to the Baptist church, now First Baptist North Middleborough. ↩︎

- Thomas Weston, History of the Town of Middleboro, Massachusetts (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1906), 405. ↩︎