World Christianity

Southwestern Journal of Theology

Volume 61, No. 2 – Spring 2019

Managing Editor: W. Madison Grace II

Introduction

One of the most fascinating stories in the history of Christian expansion is being composed in contemporary sub-Saharan Africa. The last century has witnessed phenomenal growth as traditional Africans are embracing a new faith. In many areas this expansion appears to be unstoppable with some estimates citing nearly a half a billion Africans have converted to Christianity since 1900.1 This numerical growth, along with the subsequent development of indigenous churches, has generated considerable interest of both African and Western scholarship.2

Religious change is known in the northern region of sub-Saharan Africa. At one time, the area was exclusively animistic. Today the Sahel is decidedly Islamic. Most are Malikite Sunni’s who have embraced strong Sufi traditions.3 Despite accommodation to traditional religious belief structures, this form of Islam has proven to be resistant to Christian influence. Christians are indeed present, but conversions in any significant numbers are absent. Thus, for the moment, the dominant Muslim presence seems to present a formidable barrier to the northward expansion of African Christianity.

The modern discipline of World Christian Studies seeks to document, describe, and explain the expansion of Christianity around the world. This discipline examines the condition of Christianity in indigenous contexts and seeks to understand these realities in non-western constructs. Those from an Evangelical perspective seek to do more than just to comprehend—they seek to apply that understanding to support, encourage, and even engage these Christian movements. For African scholars, numerous questions abide in the quest to understand Christian expansion into the Sahel. Particularly, are there historical precedents for religious change in the region? If so, are there lessons from the past that can influence Christian missional strategies in the present? This article will seek to demonstrate that migration leads to globalization, and that globalization leads to an increased receptivity to religious change.

Migration: Global to Local—Glocalization

The catalysts for the Islamization of sub-Saharan West Africa came from the North. They were immigrant Islamic merchants in search of gold. Their presence had a globalizing effect upon the indigenous population. Unfortunately, the term globalization has become so popular and is so widely defined that Jehu Hanciles laments that it can mean “all things to all people.” For this discussion, I will use globalization to describe “the process whereby individuals and their communities become connected to and affected by the rest of the world.”4 Glocalization then is a subset of globalization in that it describes a process whereby the global invades the local and leads to the adoption of new ideas and the establishment of new cultural norms.5 This was the history of the Middle Niger of West Africa and can be demonstrated in the following review of her history.

Islamization of West Africa

Because of the cultural depth of traditional religion in the Middle Niger, the full shift to Islam would take more than a millennium. David Robinson describes the Islamization of sub-Saharan Africa in three phases.

The first presence came from merchants involved in the Transsaharan trade. These entrepreneurs and their families lived principally in the towns, often in quarters that were labeled “Muslim.” They lived as minorities within “pagan” or non-Muslim majorities. This phase is often called “minority” or “quarantine” Islam. The second phase often goes by the name “court” Islam, because it features the adoption of Islam by the rulers and members of the ruling classes of states, in addition to the merchants. No significant effort was made to change the local religious practices, especially outside of the towns. The third phase can be called “majority” Islam, whereby the faith spread beyond the merchants and ruling classes to the countryside where most people were living.6

Each of these three stages represents a progression of both the quantity and the quality of Islam in much of sub-Saharan Africa. Islamic merchants introduced their faith to indigenous commerçants. As trade became valuable for both profit and power, political leaders of each major kingdom adopted Islam. At times, they would impose the religion on the masses. Ultimately however, it would be the European colonialists who would create the conditions necessary for the Islamization of the Middle Niger.

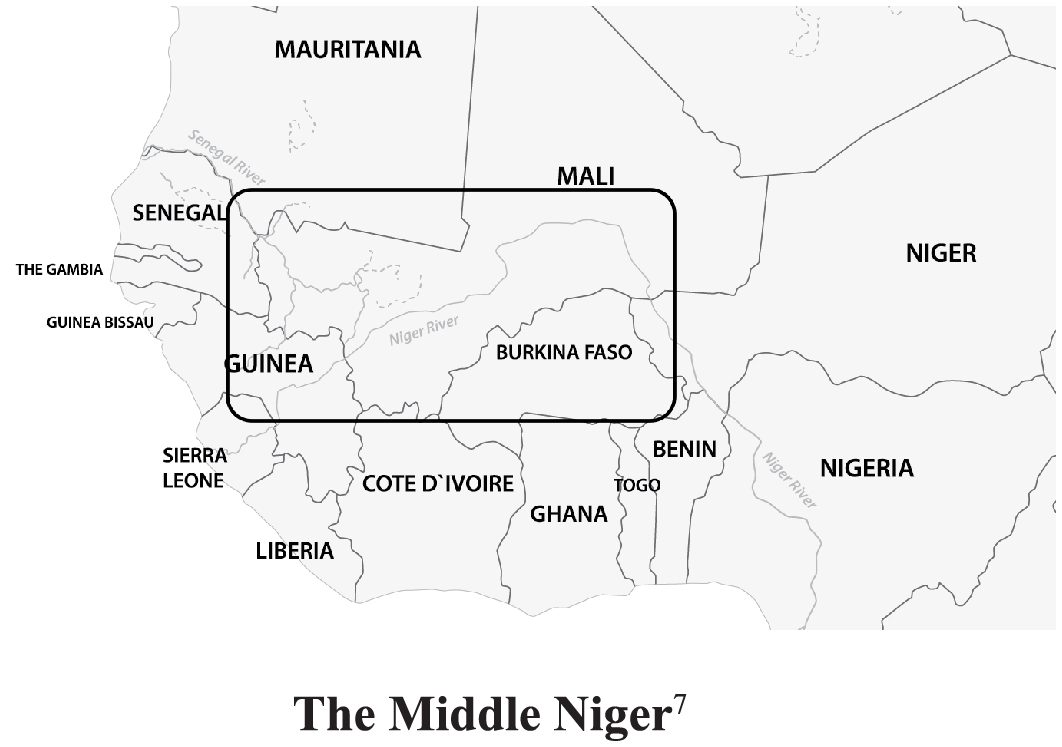

Note7

Wagadu (300–500). The Middle Niger of antiquity was geographically isolated.8 Movements of people were blocked to the North by the Sahara Desert, to the West by the Atlantic Ocean and to the South by nearly impenetrable and disease-ridden jungles. People could move to the East, but there were few reasons for doing so. Shepherds and merchants may have traveled within the region, but emigration was neither reasonable nor practical. Consequently, the people were predominantly sedentary.

External influence on the region came in stages. The introduction of the camel in the fifth century allowed for productive trade from the North. The first to make contact were Islamic merchants, who were willing to take significant risk to trade desert salt for the gold mined at the headwaters of the Niger. As they returned to their homelands bringing word of the wealth of the region, others would follow.

A written history of the Middle Niger did not begin until around 850 AD with the arrival of Muslim historians.9 They describe a region known as Wagadu to the northwest.10 The inhabitants were animist Soninke.11 Like much of sub-Saharan Africa traditional religion was central to their everyday lives and played a role in their sedentary nature. Kwabena Asamoah-Gyadu states,

African religious life was generally (and still is) bound to particular locations, sacred shrines, rivers, mountains, and caves, huts, and cattle kraals. The graves of the ancestors, the place where one’s umbilical cord was buried, and the family rural home in general, form the religious center for many Africans even if they have become modernized and live away from their traditional homes.12

In a real sense, traditional beliefs required that the people stay close to home. All their spiritual intermediaries were local. The further one would go from the graves of the ancestors, the less connected they would be. Since everything rested on the favor of these intermediaries, few things were worth upsetting the balance. This historic time and circumstance of Wagadu provide a starting point in our understanding of the western Sahel and the processes of religious change. The people would have likely remained sedentary animists for many generations were it not for the outside influence that was yet to come.

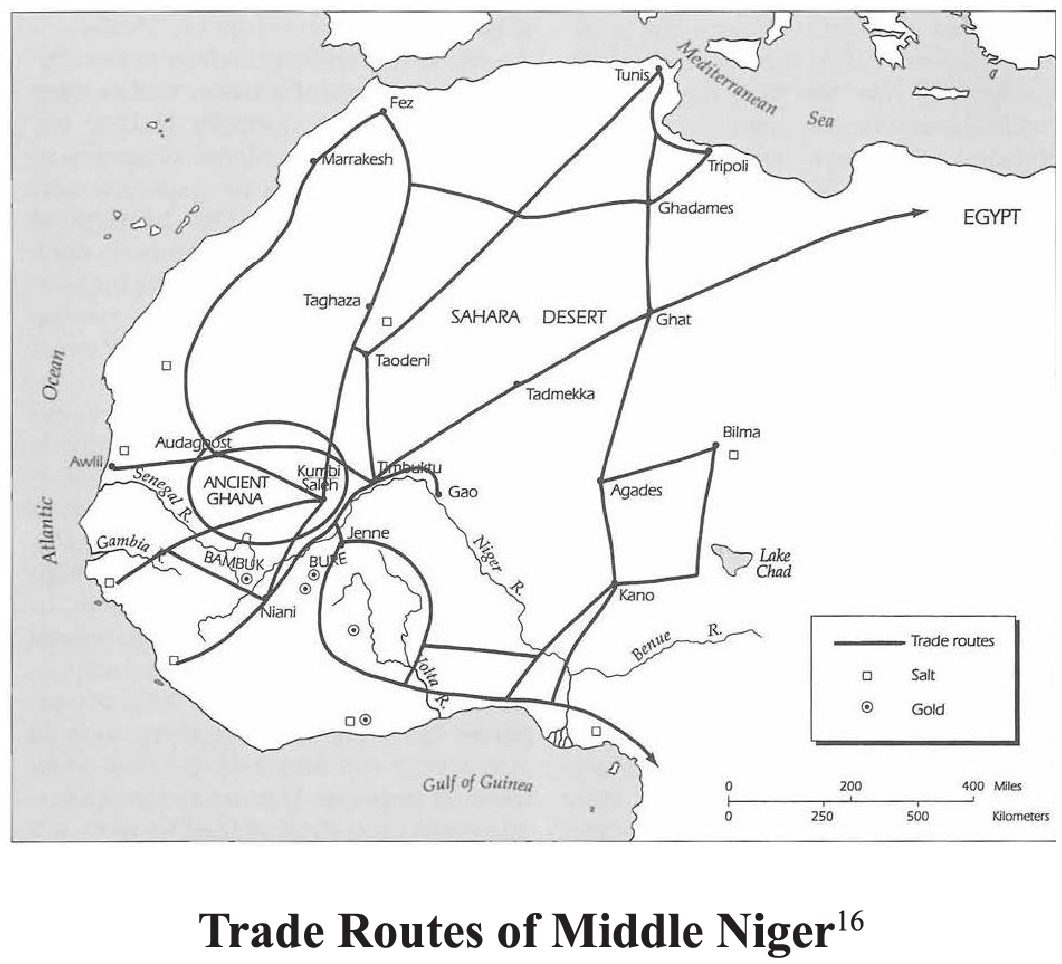

Ghana (500–1200). As noted above, developing trade was the initial conduit of religious and political change for the Middle Niger. Evolving market conditions allowed for the organization of the people of Wagadu into the Kingdom of Ghana. Vast gold reserves in the southern highlands created strong economic incentives for engagement by peoples north of the Sahara.13 Roman influence on North Africa followed by Islamic mercantile trade created a hunger for the gold of the Sudan. South of the Sahara, salt was a rare commodity except along the coast. Access to this salt in volume from the mines in the North provided excellent opportunities to establish lucrative market relationships.14

The formation of trading routes through the desert accompanied these relationships with new central routes in place as early as 1,000 AD.15 These trade routes would forever change the region. Soninke villages merged into civil societies and people clustered together around the markets for common purposes.

Note16

Thus, the kingdom of Ghana formed as these economic trading centers coalesced into unified trading blocks and political states. Because much of the commerce from the North crossed the strongly Islamic regions of the Maghreb, they also brought the influence and infusion of this new religion to the Middle Niger. For the animistic people of the Western Sudan, accommodation to religious change became an attractive, if not a necessary factor in business.

As such, the leaders and merchants of these Soninke states would become some of the first converts to Islam. Since the Animism of the populace was traditional, and the practice of Islam was foreign, adoption by the broader society would not be immediate. However, gradually it found a home among the educated elite and the economically advantaged. Thus, using Robinson’s model, Ghana entered into the Minority Stage of Islamization.17

Mali (1200–1600). In time, the kingdom of Ghana would begin to decline due to economic division and military pressures from the North.18 Other interests would rise to seek control of the gateways to the trans-Saharan trade routes. In the South, the Manden peoples populated the gold fields of the Fouta Djallon of the Sudan.19 These fields made their people very wealthy and positioned them to rise to power. They resented their Soninke overlords who had served as “middlemen” in the gold trade. Capitalizing on the weakened state of the North, their economic position enabled them to establish and then preside over a new empire that would become known as the Kingdom of Mali. The former kingdom of Ghana had been organized around city-states. In the new order, political systems would evolve around a king and associated nobility. Their centralized wealth brought the capacity to conscript an army that could secure the new kingdom.

One of their kings was particularly noteworthy. Keita (Mansa) Musa (1280–1337) expanded imperial control of the kingdom of Mali over most all the Middle Niger. By 1325 he had conquered the cities of Timbuktu and Gao to the far north and east. His broad power unified the control of trade and gave him immense power and wealth. By some accounts, he was the wealthiest person to have ever lived.20 Most notably, Musa adopted Islam and anchored Islam into the political systems of the day. As a Muslim, he made the pilgrimage to Mecca twice and in 1324 did so with great fanfare.21 His show of wealth became known throughout the Islamic world and consequently opened new and fresh markets for trade.22 The journey also exposed him to a global world and most certainly influenced his perspective of Islam.23 On his return, he brought scholars from the East to establish Islamic training centers in both Timbuktu and Gao.24

In Robinson’s model, the Kingdom of Mali represents the establishment of the “court” phase of Islamization in the Middle Niger. During this period, Islam became the dominant religion among the ruling classes, the educated and the merchants. External commercial forces exerted tremendous influence through these relationships. Even so, Mansa Musa did not impose Islam upon the people. Had he done so, there would have been a revolt. After his death in 1337, the kingdom weakened without his strong leadership and steadily declined. This weakness created opportunities for the northern states to gradually regain independent control of the valuable trading routes and commercial markets.

Songhai (1400–1600). The Songhai (Songhay) peoples along the northern bend of the Niger River capitalized on the decline of Mali and used their military prowess to control surrounding territories.25 In 1464, Sunni ‘Ali (Ber) began a broad conquest along the Niger River and ultimately established his capital in Gao, on the far eastern edge of the kingdom. Like those before him, he embraced Islam to maintain external trade and to satisfy the Soninke traders within the kingdom. When he died in 1492, one of his generals, Askia Muhammad Toure, became king.26 Under his strong rule, the Songhai Empire expanded significantly to the West and ultimately controlled the Senegal River valley from the Atlantic to its headwaters, the Hausa region of modern-day northern Nigeria and as far east as Chad.

Like Mansa Musa of the previous kingdom of Mali, Askia continued to propagate Islam, particularly among the ruling classes.27 In so doing, he maintained an environment that facilitated Islamic growth among the population. He built schools for the study and spread of Islam. He dedicated resources to strengthen the great learning center of Islamic scholars at the Sankore University in Timbuktu.28 These efforts helped him to maintain close ties with the Islamic traders on the desert side and led to the adoption of Islam by significant numbers of Songhai society.

Askia died in 1528. He was a dynamic leader and had a profound influence on the establishment of Islam among the northern ethnic groups of the Middle Niger. This, along with the strength of the Soninke merchants, the Fulani shepherds, and the Toucouleur peoples to the West, would significantly influence the spread of Islam further south. At the time, however, the lack of a suitable successor to Askia created a leadership vacuum, and the Songhai Kingdom joined the remains of the Kingdom of Mali in complete decline.

The Mali and Songhai kingdoms represent the full transition from the “Minority Stage” to the “Court Stage” of the Islamization of the Middle Niger. During this period, Islamic belief and practice had become established among the aristocracy of the courts of the two kingdoms. However, Islam had not thoroughly infiltrated into the people. This was particularly true in the South where traditional religion remained strong. They were predominantly sedentary farmers with little need for foreign merchants or their religion.

As the vast unified empires dissolved, individual kingdom-states would arise and once again assert their influence and power. Many small kingdoms would come and go, but two great movements emerged in the Middle Niger. On the one hand, the Bambara from the south would take control of the Niger River delta in the region of Segou. They fiercely rejected Islam and sought to control the region and associated trade by force. The Fulani, on the other hand, migrated away from the Futa Toro in the Northwest and spread across much of West Africa. They were committed Muslims and sought to spread Islam across the region, by compulsion if necessary. Thus, the stage was set for the ensuing conflict.

Fulani Caliphates (1600–1865). The Fulani peoples possibly descended from Morocco and settled on the western fringes of Wagadu. They formed the state of Tekruur in the ninth century and ultimately became a part of the larger empire of Ghana.29 Strategically located in the Futa Toro of the Senegal River, their region became an active trading center for the gold from the Bambuk region to the South, salt from the Awlil region to the North, and grain from the Sahel to the East.30

As allies of the Berbers and Tuaregs of the North, the people of Tekruur were positioned well and enjoyed prosperity regardless of the status of either Wagadu or Ghana. The Kingdom of Mali had risen to control the central trans-Saharan trade routes as later would the Songhai Kingdom, thereby diluting their lucrative trade market. Despite the financial decline, their location along the western corridors allowed the Fulani/Toucouleur people to retain strong trading connections with Islamic influences of the Maghreb.31

The Islamization of the Futa Toro region would follow roughly the same pattern as in the central Niger. Formal Islam in the Futa Toro was in the court stage, confined to the ruling classes, the educated, and the economically advantaged. The Arabic required to study, understand, and teach Islam was simply beyond the capacity of the common man. Thus, for Islam to truly move from the court to the majority stage, it would have to be delivered in a modified form. Those changes came with the introduction of the spiritual elements of Sufism.32

Emerging out of Sunnism in the late seventh century, Sufism was a mystical-ascetic aspect of Islam that placed greater emphasis upon esoteric divine revelation than upon typical religious forms, even the Qur’an. This form of Sufism would become synonymous with Islam as it was adopted in the Middle Niger and it would become well established by the sixteenth century. The attraction of Sufism, as it developed in the southwest Maghreb, was that it drew from the mystical elements of the traditional religious base of the populace and it allowed non-Arabic speakers to lead and practice Islam with authenticity and authority. Thus, it came in a form that could enjoy popularity among the people. Unexpectedly, however, as the spiritual devotion of the common people grew, the disparity between the basic tenants of Islamic faith and the practice of the court became evident.33 This incongruity would ultimately lead to efforts of reform.

By all accounts, Islamic reform in the Middle Niger began in the deserts of southwest Mauritania in the seventeenth century. A Muslim cleric named Nāsir al-Din called for an Islamic revival that would unite the community into a new system of governance. He sought to establish a caliphate that would stand above the desert tribal divisions in Mauritania and the political divisions of the Wolof and Futa Toro states to the south.34 While unsuccessful in creating an Islamic political center, he did spark a revival that would lead to five separate jihads among the Tukulor and Fulani.35

These Tukulor/Fulani jihads became efforts to establish regional caliphates, to ensure leaders conformed to the demands of the Islamic faith and to bring the population into proper practice. Much of the Middle Niger was still in the court stage of Islamization. The migratory Fulani sought to bring Islamic practice upon a much larger segment of the population of the southern Middle Niger, particularly in the animistic groups. These efforts represent the beginnings of the third level of Islamization suggested by Roberts, or “Majority” Islam.36

The initial methodology of the reformers was to indoctrinate local populations in Islam through charismatic teaching. Where there was resistance, such as in Bambara controlled regions, they would enforce acceptance through military prowess. Drawing from their ethnically diverse religious base, they found that they could quickly raise an army from their followers. These Fulani jihadists were successful in almost every area of engagement. Were it not for the incursion of French colonial forces in the late nineteenth century, the military power of the Fulani hegemonies would likely have fully imposed Islam upon the entire region by force. Even so, the seeds had already been sown across much of the region.

Colonial Occupation (1450–1960). European encroachment would have a significant impact on the inhabitants of the Middle Niger, their migratory patterns, and their religious practice.37 French presence equated to French control. Colonial policy gave no concern to the ongoing Fulani religious expansion in the nineteenth century, except to constrain their militant activities and seek to maintain peace. Although colonial presence prevented further jihads, it created the conditions that allowed Islam to reach the majority stage in the Middle Niger.

First, colonial rule sought to unify the people of the region by imposing French as the language of government. The Bambara people had been resistant to Islamic incursion and were willing to aid the French against the Fulani. In recognition of their assistance, the Bambara language was encouraged to become the language of commerce.38 By enforcing the use of these two languages, bridges were built across ethnic groups that would ultimately benefit Islamic expansion.

Second, colonial rule transitioned the culture from a system that was sedentary and predominantly agricultural to a cash economy. Trade, and even more importantly, taxes resulted in a need to possess French currency. The necessity of earning a wage would encourage many to migrate away from home in search of work. This separation reinforced circular migratory patterns. In so doing, isolated areas became exposed to Islamic teachings.

Finally, colonial rule created an environment that allowed the movements of itinerate, Muslim clerics. As such, they could teach the populace and encourage conversion. Islamic expansion could now follow the subtler routes into the culture without the additional baggage of political control. Given time, Islam would be adopted by the majority of the people of the Middle Niger.

Thus, as in the Middle Niger, one can readily see that glocalization, the influence of the global upon the local, can definitively effect religious change on a region or a people. It took nearly a thousand years for the region to transition from traditional religion to the minority and then the court stages of Islamization. Then, the movement to majority stage happened quickly. The population of Mali has grown from 1.3 million people in 1900 to over 19 million people today. In 1912, only 3% of the Bambara and 30% of the people in Mali were Muslim. By 2015, 95% of the Bambara and 87% of the total population had adopted Islam.39

Migration: Local to Global—Globalization

I have proposed that it was immigration that led to the glocalization and ultimately the Islamization of the Middle Niger. The region experienced religious change because of the influence of the global immigrant upon the local resident. In the modern age of globalization, I believe it will not be the immigrant who continues to effect transition, but rather the emigrant. I suggest that it will be those that leave, become exposed to a global world, and then return who will precipitate the most significant changes to their people and cultures.

Clearly, globalization is facilitated by migration. Although modernity has created diverse delivery systems of global information in the last century, it is still the human carrier that has the most profound influence upon local change. In the past, it was immigrants who came to Africa from other places. Today, the tides have turned, and emigration is the norm. Migrants leave the Middle Niger with a dream of finding a better life and hope to return to their homeland to share the spoils of their success. Many are traveling into Christianized regions and are becoming exposed to the gospel. When they return, they bring their new-found faith with them.

Migration is a Reality in Mali Today

Mali serves as an excellent example of a modern, sub-Saharan country on the move. Out of nineteen million people, more than four million of her citizens live abroad.40 Most are economic emigrants in search of a better life for their families. The majority remain in Africa, but an estimated 120,000 Malians are living in France.41 They are drawn to places like Paris, utilizing long established village or religious networks. Although the route of passage may be indeterminate, these emigrants leave with established systems of support in both their places of origin and their places of destination. If they can survive the journey, they typically have a place to land.

Those without such networks also make the journey independently, often leaving their Malian families destitute. These European immigrants, motivated by a desire to survive, follow the dangerous northern routes across the desert and the Mediterranean. Many will become the victims of human trafficking and many will either die along the journey or become enslaved in North Africa.42 Some will make it to Europe; some will be arrested and sent back.

Of those who do make it, most will join the ranks of irregular immigrants from across Africa and the Middle East. They live in refugee centers with basic supports. Each day brings a fear that they will be repatriated. Even if they can find work, they are typically abused and underpaid as they engage in the most menial of labor. It can be a very difficult life that was not expected when they left, and impossible to explain to their family back home.

By comparison to their counterparts in Mali, labor migrants are wealthy and are held in very high esteem by their home communities. Remittances by Malians abroad equates to nearly 6.5% of Mali’s Gross Domestic Product.43 For many Malian families, these resources provide their primary means of support, creating intense pressure on the migrants to secure and send funds. The sense of responsibility can be overwhelming. One Malian interviewed spoke of his family and related, “If they live, it is me that made them live. If they die, it is me that made them die.”44

The reality of migration in Mali encompasses more than just international emigrants. The internal displacement of Malians is nearly epidemic. In the past, drought-induced food insecurities were a primary cause of such movements. In 2012–13, internal conflict displaced more than a half a million people from the North. Some took refuge in surrounding countries, but many moved to the populated regions of the South.45 These rural to urban movements have led to rapid urbanization. The majority became squatters, inhabiting available vacant buildings in cities like Bamako. Poverty among this group is rampant, with many resorting to la mendiante, or begging on the streets.

As with emigration, forced displacements tend to be circular. Most of those driven out by the northern conflict in 2013 have returned to their homes.46 Even so, they maintain their citizenship in both Bamako and their local region. They do so for both security and economic interests. They seek to maintain relationships so they have a place to go if things get dangerous again. And, they continue to cultivate their economic ties as they maximize their earning potential.

Exposure to a Global World Effects Cultural Change

The impact of globalization on Malian migrants is evident. The movement from village to regional center, capital city and perhaps another country creates exposure to an increasingly broader world. Priorities expand and hesitations diminish as one is immersed in new cultures and communities. These shifts have been observed at four levels.

First, globalization introduces individualism into a collective worldview.47 Native Malians are typically born into a highly collective culture. Decision making occurs at group levels, and family hierarchies dominate most all choices. These processes extend into the most personal of affairs including religion, marriage, employment, finances and even the use of time. Emigrants pressed into new environments discover freedom from this collective control and the associated individualism is often embraced.

Second, globalization brings a changed perception of wealth.48 Mali culture holds a strong expectation that each person is responsible for contributing to the financial security of the whole. In the local worldview, the needs of the group supersede the needs of the individual. This conviction motivates most emigrants, and it remains an obligation for many. The necessity to provide for their personal needs accentuates the individualism associated with migration, and the temptation to prioritize resources for personal benefit can be intense.

Third, globalization brings an acceptance of non-traditional thoughts and activities.49 In Mali, there is a fierce tenacity to maintain religious belief and cultural practice. Gender and class roles can be quite rigid. Islamic conventions are generally inflexible. Most find that maintaining these beliefs and practices can be difficult while on migratory pathways. The necessity to engage the community in their host city can often lead to accommodation. Migrants can become adept in the art of role shifting, doing whatever is necessary to meet their daily needs.50 Yet in distant urban contexts, they very well may soften their historic convictions and adopt new systems of belief.51

Fourth, globalization brings an increased awareness of other religions.52 Most Malians are tolerant of other forms of religious practice, but they have not ever been personally exposed to anything beyond their cultural Islam. On the migratory pathway, however, things change. Some become exposed to more orthodox versions of Islam, leading to a stricter form of practice. Others become immersed in secular contexts, and their religious commitments weaken over time. Still others become exposed to Christianity and ultimately come to faith in Christ.

Many are Exposed to Christianity, Some Come to Faith

For those migrants who come to faith in Christ, the process is typically not a singular event, but rather a series of events.53 At its essence, conversion requires change at cognitive, affective, and volitional levels. One must come to a specific place in what they know about the gospel, and they must also come to a specific place in how they feel about becoming a follower of Christ.54 Interviews with Malian migrants who have come to faith indicates that the above processes of globalization were a vital component of these cognitive and affective shifts.

An excellent example of this process can be found with Abdoulaye.55 He was raised in a village in northern Mali that held to strict Islamic and cultural norms. Seeking to find food for his family, he began to travel as a young teenager. He spent four years in Senegal and Mauritania looking for work before returning home. Along the way, he heard occasional stories about Christianity. These stories did little more than catch his attention as he held to his Islamic convictions. Afterward, he traveled to France to work for his uncle on an illegally obtained visa. It was there that he became fully introduced to the gospel.

This exposure came through a chance encounter with a childhood friend named Bacary. Having left home about the same time as Abdoulaye, Bacary had spent time in the Middle East and was now working in Paris. Along his journey, he had become a follower of Christ. Their renewed relationship led to a cognitive awareness of the gospel and a dramatically changed attitude about Christianity. The message was coming from someone he understood and trusted. Over time, Abdoulaye also put his faith in Christ. He was successful in Paris and could return to Mali with the admiration of the local community. He sought out other believers around his village and was soon baptized at an evangelical mission. Abdoulaye has now spent the last three decades living his Christian faith in the village. Because of his position in the community, he carries a level of credibility and influence that has allowed him to see others come to faith.

A young pastor named Mussa is another example. When fighting erupted in northern Mali in 2012, he was one of the thousands who were displaced from his city. He fled to Bamako and began to minister to those who were discouraged and destitute. He held weekly services for the displaced believers. Within a few short weeks, the attendance had grown to eighteen families of five to ten members each. Of particular interest was one family that was not Christian, but Muslim. Their affinity with other refugees was stronger than their religious inhibitions and their displacement allowed for an increased receptivity to Christianity. Such would have never occurred in their local contexts. During his time in Bamako, both churches and mission organizations served these refugees with food, clothing, and shelter. Nearly all have now returned to their homes in the North, and the remaining believers were assimilated into local Bamako churches. For those went back, they carried their experience and exposure to Christianity home with them.56

Returning Migrants Carry Influence

Within these two short testimonies, it becomes evident that emigrants can carry significant influence in their local culture. Those who provide funds through their remittances are considered heroes among their family and community. Even from a distance, they carry a voice that can speak across cultural and religious divides. Their immersion into a global context effects change, and they then become global conduits of that change back home. Those who return to Mali will live somewhere in the minority/court stage of expression in their community. Like their Muslim counterparts of old, these emigrants return to occupy influential positions in society. Those who are believers will often find the freedom to live their faith without serious consequence. Some will occupy positions that will allow them to introduce new ideas, including the gospel.

There was once a day when the religion of the Middle Niger was animistic. Over the course of a thousand years, Islam made its way into the culture through the influence of immigrant merchants. At first, only a minority of the people adopted this new religion. In time, it was embraced by the courts of the economically privileged and the political elite. However, it was the influence of these indigenous leaders that allowed the full adoption of Islam by the people during the 20th century.

Today, Christianity is beginning to make inroads into the region and is using the same pathways as ancient Islam. In the past, it was the immigrant strangers that carried the seeds of a new religion. The global came to the local and influenced the culture. Today, religious change is coming to the Sahel through the hearts and voices of their emigrant brothers. The local is going into the global and people are being changed. They return with what they have found and it is being embraced by others. While Christianity is currently in the minority stage today, it stands poised to soon enter the court stage. Given time, it may overcome the Islamic barriers and be embraced by the majority of the people.

Conclusion

Today, globalization and urbanization have changed the complexion of the modern mission field. Over 55% of the world now lives in large urban contexts and will increase to 68% by 2050.57 Additionally, nearly one billion people, one-seventh of the world’s population can be found on migratory pathways.58 Most are making their way towards these urban centers. Many of these migrants represent ethnic groups that are considered unreached and unengaged. Fortunately, expressions of Christianity can be found in most of these urban environments, and the opportunities for these isolated peoples to become exposed to the gospel is growing. As globalized migrants, they are more open to the influence of the gospel than ever before. If they were to come to faith, most would return to places modern missionaries could not ever go with an influence they could never attain.

Throughout Christian history, the church has sought to be found obedient to the commission of Christ to “go and make disciples of all the nations.”59 She has embraced the missional process delivered to the disciples. “but you will receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you; and you shall be My witnesses both in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and even to the remotest part of the earth (Acts 1:8).” She has been faithful to offer a Spirit-empowered witness at home and abroad. The moment each of these missionaries left their Jerusalem, they also became migrants. As such, their pathways took them to familiar places like Judea, foreign places like Judea, and at times, faraway places that were completely unknown.

There was once a day when going to the unknown was critically necessary. If the missionary did not go, the people that lived there would never hear. That day has changed. Today, unreached people from the remotest parts of the earth are on the move. They are migrants, and as such share a common connection to the missionary migrants that they meet along the way. Together they walk similar pathways and experience similar challenges. It is at these intersections, this middle ground of Judea and Samaria where those who were once far away and inaccessible are now close and open to conversation. They can now step beyond their cultural and religious restrictions and into a place to truly hear and respond to the message of Christ. In the end, it may well be these migrants who will become missionaries to their fellow migrants and their community back home.

- Philip Jenkins, The Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity, 3rd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 3. Between 1900 and 2010, Christianity in Africa grew from 10 million to 493 million believers. By 2050, the number is estimated to be over one billion. ↩︎

- Numerous scholars have written prolifically on the expansion of Christianity in Africa. The literature includes World Christian Studies (WCS) authors such as Andrew Walls, Philip Jenkins, Afe Adogame, and Jehu Hanciles. ↩︎

- David Robinson, Muslim Societies in African History, New Approaches to African History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 95. ↩︎

- M. Augustus Hamilton, “Analysis of the Dynamic Relationship between Globalization and the Transmission of the Gospel: A Case Study of Soninke Transmigrants in Africa and Europe” (Ph.D. diss., Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, 2017), 183. ↩︎

- See Roland Robertson, Globalization: Social Theory and Global Culture, Theory, Culture & Society (London: Sage, 1992), 173–74. See also Os Guinness and David Wells, “Global Gospel, Global Era: Christian Discipleship and Mission in the Age of Globalization,” (2010), 5/12. ↩︎

- Robinson, Globalization, 28. ↩︎

- Map of the Middle Niger by Ben Hamilton. Used by permission. ↩︎

- The Middle Niger of today includes portions of Mauritania, Senegal, Mali, Algeria, Niger, Libya, Chad, and Sudan. The region encompasses over 45 million people and more than 215 people groups. See “Desert Peoples: Reaching the Unreached,” Commission Stories, International Mission Board, 2013, accessed 1 December 2014, http://www.commissionstories.com/africa/interactives/view/of-the-215-people-groups-on-the-southern-edge-of-the-sahara-desert-more-tha. ↩︎

- Timothy Geysbeek, “History from the Musadu Epic: The Formation of Manding Power on the Southern Frontier of the Mali Empire” (Ph.D. diss., Michigan State University, 2002), 17–18. ↩︎

- For a fuller examination of the history of the Middle Niger, see Dorothea Elisabeth Schulz, Culture and Customs of Mali, Culture and Customs of Africa (Santa Barbara, CA.: Greenwood, 2012), 4. See also, Patrick R. McNaughton, “The Bamana Blacksmiths: A Study of Sculptors and Their Art” (Ph.D. diss., Yale University, 1977), 4. ↩︎

- Eric Pollet and Grace Winter, La Société Soninké (Dyahunu, Mali), ÉTudes Ethnologiques (Bruxelles: Éditions de l’Institut de Sociologie, 1972). The Soninke are a distinct ethnic group in the Middle Niger today. They are the descendants of the peoples who populated the historic region of Wagadou. ↩︎

- Frieder Ludwig and J. Kwabena Asamoah-Gyadu, African Christian Presence in the West: New Immigrant Congregations and Transnational Networks in North America and Europe (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 2011), 336. ↩︎

- Claude Meillassoux, Urbanization of an African Community: Voluntary Associations in Bamako, American Ethnological Society Monograph (Seattle,: University of Washington Press, 1968), 76. ↩︎

- See François Manchuelle, “Background to Black African Immigration to France: The Labor Migrations of the Soninke 1848–1987” (University of California, 1987), 32. ↩︎

- See Ade Ajayi and Michael Crowder, History of West Africa, 2 vols. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1972), 1:139–40. See also Philip Koslow, Ancient Ghana: The Land of Gold, Kingdoms of Africa (New York: Chelsea House, 1995), 27. ↩︎

- Philip Koslow, Songhay: The Empire Builders, The Kingdoms of Africa (Philadelphia: Chelsea House Publishers, 1995), 34. ↩︎

- Robinson, Globalization, 28. ↩︎

- See Ajayi and Crowder, 1, 128–30. And Pascal James Imperato and Gavin H. Imperato, Historical Dictionary of Mali, 4th ed., Historical Dictionaries of Africa (Lanham: Scarecrow, 2008), 2. ↩︎

- For an excellent discussion on the region, see Ajayi and Crowder, History of West Africa, 1:119. ↩︎

- “The 25 Richest People Who Ever Lived—Inflation Adjusted,” Celebrity Net Worth, 2014, accessed 1 October 2018, https://www.celebritynetworth.com/articles/entertainment-articles/25-richest-people-lived-inflation-adjusted/. ↩︎

- Djibril Tamsir Niane, “Sundiata and Mansa Musa: Architects of Mali’s Golden Empire,” The UNESCO Courier, August-September (1979). ↩︎

- Nubia Kai, Kuma Malinke Historiography: Sundiata Keita to Almamy Samori Toure (1972), 251. See also John Coleman De Graft-Johnson, African Glory: The Story of Vanished Negro Civilizations (New York: Walker, 1966), 97. By today’s standards, Mansa Musa may have been the wealthiest person to have ever lived. On this one Hajj, he led a caravan of over 6000 porters of gold, and its length exceeded 40 miles. It is reported that he distributed so much gold in Cairo that it depressed the gold market there for years to come. His show of wealth placed the Kingdom of Mali at the center of all Islam and trade in sub-Saharan Africa. ↩︎

- J. Spencer Trimingham, A History of Islam in West Africa, University of Glasgow Publications (London: Oxford, 1970), 71. See also, Lamin O. Sanneh, “The Origins of Clericalism in West African Islam,” The Journal of African History, 17, no. 1 (1976): 51. ↩︎

- Hammadou Boly, “La Soufisme Au Mali Du Xixeme Siecle a Nos Jours” (Ph.D. diss., Universite de Strasbourg, 2013), 32. These scholars would play a significant role in the Islamization of the northern sector of the Middle Niger. The infusion of this Eastern Islamic tradition upon the local culture (glocalization) was instrumental. These religious leaders indoctrinated their students, who would then carry Islam into the smaller towns and villages. ↩︎

- There are multiple people groups in the region. The Soninke were to the West, Manden were to the South, and Songhai were to the East in the region of Timbuktu. ↩︎

- Ajayi and Crowder, History of West Africa, 1:228. See also Imperato and Imperato, 21. The Askia’s were a dynasty of eleven kings, who ruled over much of the Songhai Empire in the 16th century. ↩︎

- See Philip Koslow, Songhay: The Empire Builders, The Kingdoms of Africa (Philadelphia: Chelsea House Publishers, 1995), 24. See also Pat McKissack and Fredrick McKissack, The Royal Kingdoms of Ghana, Mali, and Songhay: Life in Medieval Africa, 1st ed. (New York: H. Holt, 1994), 96–99. This marked a significant change. Formerly, the adoption of Islam was for economic and political purposes. Now it would appear that the adoption was much more solidified. ↩︎

- McKissack, The Royal Kingdoms of Ghana, Mali, and Songhay, 100. ↩︎

- See also John H. Hanson, Migration, Jihad, and Muslim Authority in West Africa: The Futanke Colonies in Karta (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1996), 25; and also, B.O. Oloruntimehin, The Segu Tukulor Empire, Ibadan History Series (London: Longman, 1972), 7–8. The Fulani (Peul or Fulbe) are predominantly a nomadic pastoral people. Early settlements were established in this region due to the availability of water. Once there, a segment joined with the local population and became sedentary, establishing a culture of agriculture and fishing. They became known as the Toucouleur. The nomadic non-Toucouleur Fulani continued to migrate extensively across the Middle Niger, managing their livestock and engaging in trade. ↩︎

- Philip Koslow, The Lords of the Savannah: The Bambara, Fulani, Igbo, Mossi, and Nupe, The Kingdoms of Africa (Philadelphia: Chelsea House, 1997), 20. ↩︎

- William J. Foltz, From French West Africa to the Mali Federation, Yale Studies in Political Science (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1965), 5. ↩︎

- For an excellent discussion of Sufism in the Futa Toro, see Robinson, Globalization, 27. ↩︎

- This is not to imply that the leaders were not Sufi. It is intended to highlight the differences between court Islam and majority Islam. Court Islam utilized Islamic practice for political and economic purposes. Since the populace had access to neither, they would adopt Islam for religious purposes, and thus grew weary of the hypocrisy of their leaders. It would be this frustration that would fuel the popular reform movements. ↩︎

- Philip Curtin, “Jihad in West Africa: Early Phasis and Inter-Relations in Mauritania and Senegal,” The Journal of African History 12, no. 1 (171): 14–16. ↩︎

- Curtin, “Jihad in West Africa,” 15. Jihad should not be interpreted to mean warfare against conflicting ideologies. It is a struggle for something, such as reform. It would only be in the late periods that the jihads were characterized by warfare and destruction. ↩︎

- Robinson, Globalization, 28. ↩︎

- Efraim Karsh, Islamic Imperialism: A History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), 69–70. ↩︎

- Sundiata A. Djata, “Fanga: The Bamana in the Middle Niger 1830–1910” (Ph.D. diss., University of Illinois, 1994), 302. ↩︎

- Ira M. Lapidus, A History of Islamic Societies (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 736. See also, Todd M. Johnson and Gina A. Zurlo, “World Christian Database” (Boston: Brill, 2007). ↩︎

- Diana Cartier, “Mali Crisis: A Migration Perspective,” (Geneva: International Organization for Migration, 2013), 6. ↩︎

- “Qui Sont Les Maliens De France?,” Lemonde, 2013, accessed 1 October 2018, https://www.lemonde.fr/societe/article/2013/01/18/qui-sont-les-maliens-de-france_1818961_3224.html. ↩︎

- Amélie Gatoux, “Mmc West Africa August 2018: Monthly Trends Analysis,” (Dakar: Mixed Migration Center, 2018). ↩︎

- 3“World Bank Mali Country Profile,” World Bank, 2018, accessed 1 October 2018, https://data.worldbank.org/country/mali. ↩︎

- Hamilton, “Analysis,” 292–93. ↩︎

- Cartier, “Mali Crisis: A Migration Perspective.” ↩︎

- “Rapport Sur Les Mouvements De Populations,” (Bamako: International Organization For Migration, 2018). ↩︎

- Hamilton, “Analysis,” 200. ↩︎

- Hamilton, “Analysis,” 202. ↩︎

- Hamilton, “Analysis,” 203. ↩︎

- Zain Abdullah, Black Mecca: The African Muslims of Harlem (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 13. ↩︎

- Guvnor Jónsson, “Migration Aspirations and Immobility in a Malian Soninke Village” (Oxford: International Migration Institute, 2008), 17. ↩︎

- Guinness and Wells, “Global Gospel, Global Era,” 221–22. ↩︎

- Reinhold Straehler, “Coming to Faith in Christ: Case Studies of Muslims in Kenya” (D.Th. diss., University of South Africa, 2009), 54. ↩︎

- “Coming to Faith in Christ: Case Studies of Muslims in Kenya” (University of South Africa, 2009). ↩︎

- Hamilton, “Analysis,” 337. The story of Abdoulaye was recorded as a focused oral interview. For security purposes, the material was de-identified. Abdoulaye is not his real name, and he was referenced as PP in the study. ↩︎

- Interview with Dr. Mohammad Yattara, Bamako, 26 September 2018. ↩︎

- “World Urbanization Prospects: 2018 Revision,” United Nations, 2018, accessed 4 October 2018, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.URB.TOTL.IN.ZS?end=2017&start=1960. ↩︎

- Marie McAuliff and Martin Ruhs, “World Migration Report 2018,” ed. Marie McAuliff and Martin Ruhs (Geneva: International Organization for Migration, 2018). ↩︎

- Matthew 28:19, Unless noted otherwise, all Scripture references are from the New American Standard Version. ↩︎