Christ and Culture Revisited

Southwestern Journal of Theology

Volume 64, No. 2 – Spring 2022

Editor: David S. Dockery

What does it mean to be a godly Christian citizen today? Does this differ for a Christian living in a republic like the United States, a Muslim-majority country like Iran, a Communist dictatorship like Cuba, or any of sixteen different types of governments1 in 197 different countries?2 Does the New Testament address Christian citizenship, and is it still relevant to twenty-first-century Christians?

The word “citizen” is rare in the NT: the noun form of the “citizen/commonwealth” cognate group appears only once in the NT (politeuma in Phil 3:20) and the verbal form appears only twice (politeuomai in Acts 23:1 and Phil 1:27). Yet, the NT teachings on this important issue are relevant to twenty-first-century Christians. This article will demonstrate Christian citizenship is best understood as dual citizenship of concentric kingdoms. After establishing the model based on the primary NT teachings,3 there will be six NT applications: (1) using courts, (2) taking an oath in court, (3) serving as a soldier or peace officer, (4) voting, (5) holding office, and (6) participating in civil disobedience or revolution.

I. CONCENTRIC KINGDOMS

All NT writers wrote and lived in the first-century AD Roman Empire.Yet, they addressed three different geopolitical areas. For instance, the Christian recipients of Paul’s letter to the Romans were in a much different political situation than the Christian “sojourners”4 (parepidēmois, 1 Pet. 1:1) in Asia Minor to whom Peter wrote 1 Peter. First, Jesus ministered in Palestine, and Syria/Palestine had been under Roman control since 63 BC. It had few Roman citizens, and Rome considered most inhabitants to be peregrini (“aliens”).5 Rome usually allowed Jews freedom to exercise their religion as Rome typically did in conquered areas. The early church enjoyed this same freedom for a while because outsiders considered them a Jewish sect at first. In addition, there was indirect Roman rule through the local, provincial rule of Herod Antipas, tetrarch of Galilee and Perea. There was direct Roman rule through Pontius Pilate, procurator of Judea and Samaria—appointed directly by Tiberius since AD 26. In addition, the Jewish Sanhedrin and the high priest, Caiaphas, retained limited religious power. Second, Paul wrote to Christians in Rome. It had a much higher percentage of Roman citizens than the rest of the empire. Yet, there were so many slaves in Rome that they may have been the majority population in this huge metropolis. Third, Paul, Peter, and John wrote to Christians in Mediterranean cities which ranged from provincial cities with many Roman citizens, such as Ephesus and Philippi, to cities with few Roman citizens, such as the island of Crete and the Galatian province.

This study will first examine Jesus’s teachings about God’s kingdom and earthly kingdoms. These passages are foundational for all subsequent NT passages on the subject. Then it will investigate the other relevant NT passages in canonical order.

1. Render to Caesar (Matt 22:15–22; Mark12:13–17; Luke 20:20–26). Understanding Jesus’s statement on taxation is key to comprehending how his followers should relate to the state. Although he addressed only taxation, the principle behind it is likely connected with other major NT teachings on the state.6 The Jews found Roman occupation taxing—literally! They hated paying what they considered oppressive taxes to the occupying power and thought tax collectors to be terrible sinners.7 The tax Jesus addressed in this passage was the tribute tax (poll tax) that the inhabitants of Roman colonies paid in denarii.8 These Roman coins bore a picture of the Roman Emperor, and Jews considered all images idolatrous based on the fourth commandment (Exod 20:4).

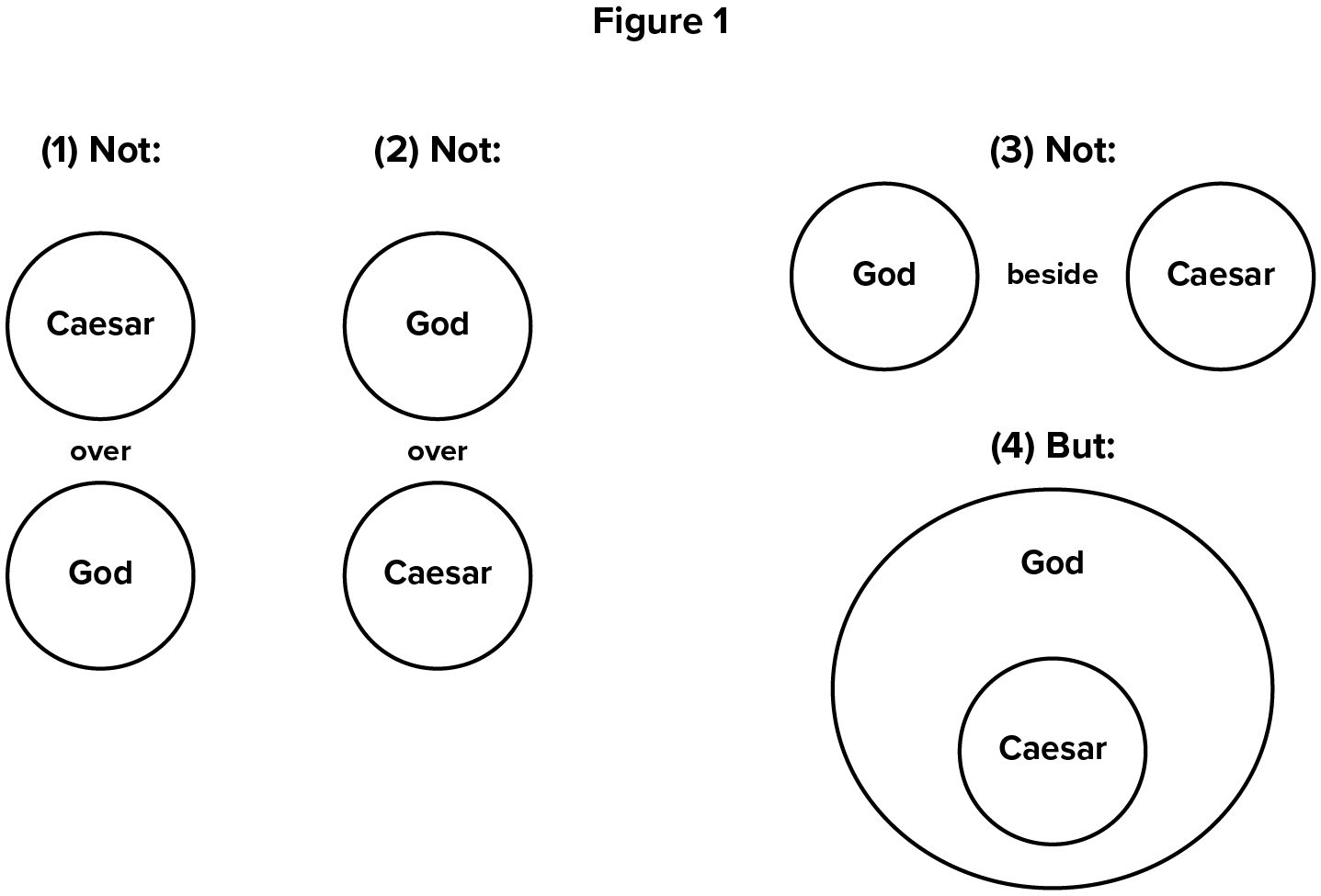

On Tuesday of the Passion week in Jerusalem, Pharisees and Herodians, who frequently opposed each other, joined to present a theological conun- drum to trap Jesus. They assumed Jesus would be in trouble regardless of how he answered the question: to whom does one owe tax? He would favor either Caesar or God and be branded a collaborator or a revolutionary. However, Jesus saw their “wickedness” (ponērian) and realized they were testing him (Matt 22:18). His surprising response was that people should give to Caesar what is his and to God what is his (v. 21). In this answer, Jesus said the two realms of authority do not necessarily contradict.9 Although Jesus addressed only taxes in his answer, the relationship he described between God’s rule and Caesar’s rule helps clarify other matters about citizenship. God’s realm is everywhere and includes everything, yet he gives limited authority to earthly rulers. This concept fits what Jesus told Pontius Pilate three days later: “You have no authority over me except what has been given to you from above” (John 19:11). Thus, the situation is not: (1) Caesar over God or (2) God over Caesar—the only two choices the questioners expected. Nor is it (3) two separate realms of God and Caesar, but it is (4) God gives Caesar limited authority within God’s greater realm. Thus, one can “be both a dutiful citizen and a loyal servant of God.”10

Thus, Caesar has limited authority, given to him by God.11

By asking for a denarius to use as an object lesson, Jesus emphasized that the Jews were enjoying the benefits of Roman rule. They were to “give back” (apodote) what was essentially already Caesar’s.12 This verb implies a moral obligation to the state. The questioners “marveled” (ethaumasan) at Jesus’s answer (Matt 22:22). They were not expecting him to be able to answer the question without turning either the Jews or the Romans against him.

2. Simon’s statēr (Matt 17:24–27). An earlier statement by Jesus in Capernaum addressed a different tax on the Jews: the annual half-shekel temple tax on every Jewish male over the age of twenty. Jewish leaders based this religious tax on Exod 30:13; 38:25–26. In this event, Jesus and his disciples passed through Galilee on their way to Jerusalem. In Capernaum, some tax collectors asked Simon Peter if Jesus did not pay the “double drachma [tax]” (v. 24), which was an amount roughly equivalent to a half shekel. Although it was a religious tax, the state provided tax collectors outside of Jerusalem.13

In a subsequent conversation with Peter, Jesus said he and his followers were exempt from this tax, no doubt because they were doing God’s business. However, so as not to give offense, Jesus told Peter to cast a line into the sea and a fish would have a statēr in its mouth.14 This coin was close in value to a shekel, and it would pay the half-shekel temple tax for Jesus and Peter. Since Matthew recorded this event, one ought to assume Peter obeyed Jesus and caught a statēr-bearing fish.15

Many scholars dismiss this passage as a distorted report or unlikely miracle,16 but there is no compelling reason to doubt such a minor miracle occurred. However, it concerned a religious tax about the temple which Jesus was about to make obsolete. So, the applicable lesson for today is simply not to offend others.

3. Acts incidents. The disciples discovered soon after Jesus’s ascension that blind obedience to all civil and religious leaders was untenable. On two occasions, the Sanhedrin—the highest religious authority in Judaism— firmly forbade the disciples from speaking about Jesus (Acts 4:17–18; 5:28). The second warning included flogging (v. 40). Yet, on both occasions, the disciples refused to obey the order—invoking the higher authority of God. At the second encounter, they said, “we must obey God rather than people” (5:29). Thus, they interpreted Jesus’s teachings about relating to government to include disobeying directives by officials that violated God’s commands. It was ironic that the first persecution of Christians came from religious authorities, the Jewish Sanhedrin; however, Jesus had predicted this would happen (John 16:1–2).

Luke was careful in Acts to show neither Paul nor other Christians disobeyed the Roman government. Civil authorities jailed Paul and Silas without cause in Philippi (Acts 16:37), Caesarea Maritima (Acts 24:12–16), and Rome (Acts 26:31–32). Paul never bribed procurators Felix (Acts 24:26–27) and Festus.17 Presumably, he bribed no one else. Paul was declared innocent by commander Claudius Lysias (Acts 23:26–29), procurator Festus (Acts 26:31–32; 28:18), and King Agrippa II (Acts 26:32).

Christians usually did not ask the state for help when others wronged them. Yet, in circumstances which the state had to settle, Paul did not hesitate to call upon its help and protection. Several times Paul insisted on the benefits of his rights as a Roman citizen (Acts 16:35–39; 21:39; 22:23–30). He accepted the protection of Roman soldiers (Acts 21:31–40; 22:23–30; 23:10–35). He informed a Roman officer of the plot for his death to foil would-be assassins (Acts 23:11–22). Trying to ensure his rightful acquittal, he appealed to the emperor (Acts 25:10–12, 21, 25; 26:32; 28:19). Evidently, Paul expected justice from the state. According to church tradition, he was obedient even to the point of his own martyrdom.18

4. Subjection to the state (Rom 13:1–7). Romans 13:1–7 contains Paul’s longest and most important teaching about government. Yet, Gorman says it is “among the most difficult, potentially disturbing, and even possibly dangerous of all Pauline texts…[used to] support the divine right of kings, blind nationalism, and unquestioned loyalty to rulers—even tyrants.”19 Indeed, some German churches used this text to justify their support of Adolf Hitler.

This passage appears in the application section of Romans, chapters 12–15. It sits between a section about Christians’ relationships with insiders and outsiders (12:3–21) and Christians loving others (13:8–10).20 Rather than a non-Pauline interpolation, 13:1–7 continues the theme of relating to outsiders.21 The Roman church receiving this letter was likely composed of house churches—some consisting mainly of Gentile Christians and others mainly of Jewish Christians. Oakes describes Christian attitudes to Rome in the mid-AD 50s as “awe, appreciation, resentment, contempt, denial of ultimate authority, expectation of overthrow.”22 There are many theories as to the impetus behind Paul’s exhortation in this passage to Roman Christians.23 Likely there were disagreements over whether to pay taxes and how much a Christian should obey governing authorities.24 So, Paul addressed these issues. One must interpret this biblical text in its most natural sense. For instance, there is no reason to see it as a subversive call to rebel against Roman authority.25 There are five key phrases in this passage. First, who are the “governing authorities” (exousiais hyperechousais, v. 1)? Cullmann argues for both rulers of this world as well as the invisible, demonic powers behind them.26 Yet, the present pagan governments specifically, and earthly governments generally, best fit the context of verses 1–7.27 Second, how are they “appointed (or ordered) by God” (tetagmenai eisin, v. 1)? The positivistic view says God providentially establishes each government; the normative view believes God establishes the principle of government, and he brings individual governments in line to his purpose; and the orderly view says God simply brings governments into order.28 Third, what does it mean “to be subject to” (hypotassesthō, v. 1) these authorities?29 Does it denote more of a recognition of authority rather than an unquestioning obedience? Kruse says “submit” here means to submit “willingly, but not uncritically”—for there will be times government commands contradict God’s rules.30 Fourth, how are authorities “a minister of God” (twice in v. 4) and “servants of God” (v. 6) in a pagan or evil government?31 They are ministers of God when they keep law and order and punish evil doers as they “bear the sword” and “bring wrath” (v. 4) upon them. Thus, the propagation of the gospel can continue. Fifth, what kind of “sword” (machairan) does the state bear? It is just a small dagger the Roman police used to keep the peace,32 or does it include capital punishment? The latter seems more likely since this term appears elsewhere in the NT in connection with violent death (i.e., Acts 12:2; Heb 11:34, 37).33

Romans 13:7 lists the need to pay direct tax (phoron) and indirect tax (telos). The former included poll tax and land tax, and it may relate to imperial subjugation of conquered lands.34 The latter contained toll taxes and customs duties, taxes on goods and services. Roman citizens were not exempt from indirect taxes.35 Yet, Paul addresses much more than just paying taxes. This verse also says to give authorities the intangible obligations of “respect” (phobon)36 and “honor” (timēn). Interestingly, Roman law also punished people who were ungrateful for benefaction.37

Was Paul too simplistic about government in this passage? It is untenable that Paul naively considered governments as only benevolent. First, it is highly likely he knew of the abuses by Herod Antipas, Pontius Pilate, Tiberius, Caligula, Nero, and others. Second, he was beaten without cause and jailed by authorities in Philippi (Acts 16:23). When Paul wrote this passage, most government officials were pagans. Yet, the religion of the authorities is not the point of the passage. Nor did Paul say leaders would never abuse their authority. Rather, they are God’s appointed leaders. This passage is still applicable today regardless of what kind of government one lives under. James Leo Garrett aptly summarized this passage: “Obedient submission to the governing authorities of the civil state is a Christian duty because civil authority is ordained by God.”38

5. More on subjection (1 Tim 2:1–2; Titus 3:1–2). Two of the last three epistles Paul wrote reflect his basic thought in Rom 13:1–7. He urged Timothy (and the church at Ephesus) to make “entreaties, prayers, intercessory prayers, and thanksgivings” for all people and specifically for “all who are in authority” (1 Tim 2:1–2).39 It is significant that prayers and thanksgivings were to be offered for the current Neronian government with persecution so imminent.40 Prayers could be for their salvation, for God’s guidance for them, for conditions conducive for evangelism, and thanksgiving to God (which Paul mentioned). The goal of a “quiet and peaceful life” in 1 Tim 2:2 fits Paul’s stated purpose of government in Rom 13 of keeping law and order. Paul told Titus to remind Cretan Christians “to be subject to” (hypotassesthai) “rulers and authorities” (including local authorities) and “to obey” (peitharchein)41 them (Titus 3:1)—the latter term being a new addition to his teaching. “Obey” is not problematic if it is understood to apply only when government does not contradict God’s laws.

Elsewhere Paul referred to the temporary nature of civil governments and even religious rulers, such as the Sanhedrin, and their tendency toward injustice in 1 Cor 2:6–8. He described a Christian’s ultimate submis- sion to God since one’s true citizenship is in heaven (Phil 3:20). Thus, every Christian is a citizen of God’s kingdom and a citizen or resident of an earthly kingdom—concentric kingdoms as Jesus taught. Paul also described “the restrainer” in 2 Thess 2:6–7. If “to katechon…ho katechōn” refer to the state or general world order as the restrainer of the man of lawlessness, this would be Paul’s earliest mention of the law-and-order purpose of the state. However, if the restrainer is the Holy Spirit, as this writer contends, Paul did not mention the state in this passage.

6. Peter’s perspective. Assuming Petrine authorship, this writer dates 1 Peter ca. AD 63, just prior to Nero’s orchestrated persecution of Christians. Peter says to “submit yourselves” to “every human institution,” including kings and “governors” (hēgemosin, 1 Pet 2:14)—a statement like Rom 13:3–4. Christians should be “those who do good” (v. 14): obeying the laws and doing deeds for the betterment of society.”42 Is this a naïve expectation that government will always be benevolent? No. First Peter 4:12–17 addressed strengthening the Christians in Asia Minor for both present and coming persecution. The “burning ordeal” (v. 12) included present persecution from unbelieving Jews and local officials as well as coming persecution from the Roman government.43

Peter’s exhortations reflect some of Paul’s same themes of subjection to and the purposes for government. Yet, he wrote his epistle later than Paul’s letters and more clearly reflected the darker, abusive side of the state. Peter’s attitude to the state is a good link between the earlier and the later apostolic age.

7. The evil empire in Revelation: A game changer? Except for the persecutions of Christians under Nero (mid-to-late 60s) and Domitian (early-to-mid 90s), the attitude of the Roman Empire towards Christians in the first century AD was mostly benign. However, Revelation shows a stark difference with the evil empire starting in chapter 6 and reaching a crescendo in chapters 17–18. Does this make obsolete the earlier NT statements about Christians and government? Does this new situation break the paradigm?

Most scholars agree Revelation was written during the Neronian or Domitian persecution. This writer believes it also describes a future government that will be worse than the present one under Domitian: one that will be evil, anti-God, and anti-Christian.44 Here is a government doing the opposite of its God-given tasks of punishing evildoers, keeping order, and praising people who do good. For instance, there will be much Christian martyrdom during this time (Rev 6:9–10). Although it depicts a time when there will be many more situations of needing to obey God rather than government, Revelation does not contradict nor negate earlier NT teachings concerning Christian citizenship.

Thus, the NT model is dual citizenship of concentric kingdoms, and this includes paying taxes and obeying laws that do not contradict God’s laws. However, the NT has more to say about Christian citizenship. Here is a brief examination of six applications of Christian citizenship.

II. NEW TESTAMENT APPLICATIONS OF CITIZENSHIP

1. Using courts. Did Paul tell the Corinthian Christians not to go to courts of law in 1 Cor 6:1–8? If so, is such teaching normative for all Christians? This passage is often misapplied because of a failure to understand the context. Paul was not forbidding Christians from going to law courts. Paul himself used the courts or law representatives when appropriate, appealing to a Roman commander (Acts 22:25–29), two Judean governors (24:10–21; 25:8–9), and the emperor (25:10–12). The context of 1 Cor 6:1–8 is civil law, not criminal law. Paul said a Christian must not take another Christian to court, so this refers to civil matters. The church should arbitrate in such matters.45 Sadly, in Corinth some Christians were taking other believers to court over trivial matters and letting unbelievers make decisions a believer was better equipped to make than a pagan judge or jury was (1 Cor 6:1, 7–8).

Paul did not address criminal matters in this passage. In a criminal matter, it is the city, state, or federal government rather than an individual that brings the accused to court. So, 1 Cor 6:1–8 has no application in criminal matters such as child abuse, spouse abuse, robbery, or other crimes against the state. A Christian has a duty to report a crime to the authorities. Keeping society safe by punishing evildoers is one of the main God-given functions of government (Rom 13:3–4). God’s purpose for government prohibits vigilante justice. Matters of punishment must be left to government action rather than to an individual or self-appointed group.

2. Taking an oath in court. In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus said not “to swear/take an oath” (Matt 5:34). Instead, one should say, “Yes, yes; no, no” (v. 37). James wrote something similar in Jas 5:12. In the Passion week, Jesus rebuked the Pharisees and scribes for their deceptive system of oath giving (Matt 23:16–22). So, giving deceptive oaths is wrong, but Jesus said not to make any oath. Rather, one should be such a person of integrity that people accept your word at face value and do not require you to take an oath for verification.

Some Christians use Matt 5:33–37 to refuse signing a pledge card for a church budget or building program even though they have no problem signing a commitment to pay their monthly mortgage, cell phone, and electric bills.46 Are these valid applications? It seems not. They are not making oaths; they are making commitments. It is not biblically wrong to make a commitment, but it is wrong to break a commitment.47 Others cite this passage and refuse to take an oath in a court of law. Yet, this application also seems invalid. Taking an oath in a court of law is necessary because it is in front of people who do not know you and need some validation of your testimony, and Jesus was likely not referring to such action but addressing conversations with people who know you.

3. Serving as a soldier or peace officer. Did Jesus promote pacifism? Is war ever justifiable? May a Christian serve as a peace officer or in the military? There are two passages some Christians cite to claim Jesus promoted pacifism. First, in the Sermon on the Mount Jesus said to “turn to him also the other [cheek]” (Matt 5:39). Was this a prohibition against all fighting? No. Using one’s right hand (presumably) against the right cheek of another person is not a fight. Rather, Jesus referred to a backhanded slap of the right hand: an insult. So, allow people to insult you all day long. Second, in the same sermon Jesus said to “love your enemies” (5:44). Does loving one’s enemy forbid Christians from serving in the military or as a peace officer?

Five NT passages preclude pacifism and give insight to this issue. First, as forerunner to the Messiah, John the Baptist preached consistently what Jesus taught later. John told soldiers how to show true repentance, and it did not involve quitting their occupation (Luke 3:14). Second, Jesus did not explicitly address if his followers should serve in the military or as peace officers, but he implicitly affirmed it. He healed a centurion’s servant and praised the great faith of the centurion (Matt 8:10, 13), whom Jewish elders highly regarded (Luke 7:4–5). Jesus mentioned nothing about that occupation being inherently sinful. Third, the first conversion of a large group of Gentiles came through Peter’s preaching at the home of a centurion named Cornelius—a devout God fearer (Acts 10:1–2, 22, 30–32, 35). Fourth, another affirmation of these occupations being fit for Christians occurs in Paul’s description of the God-given mandate for government to “bear the sword” (Rom 13:4), which presumably involves keeping the peace domestically through peace officers and soldiers as well as protecting the state from outside threats through soldiers. Fifth, Paul used a trifold metaphor for Christian discipleship: soldier, athlete, and farmer (2 Tim 2:3–6). He likely would not have used a sinful occupation in these examples, such as being a hard-working thief!

What about the bad actions of soldiers and guards in the NT? For example, (1) soldiers scourged Jesus, put mock royal attire on him, and beat him (John 19:1–3), (2) soldiers crucified him (vv. 17–18), (3) they pierced his side with a spear (v. 34), (4) the temple guard thrice arrested Peter and John at the temple (Acts 4:1–3; 5:17–18, 26–27) and flogged them after the third arrest (v. 40), (5) soldiers illegally beat Paul and Silas at Philippi (Acts 16:22–23),48 (6) soldiers wanted to kill all prisoners when Paul’s prisoner ship wrecked near Malta (Acts 27:42), and (7) soldiers will gather to fight for the Antichrist in the future (Rev 19:19). Yet, examples of wrongdoing do not invalidate these occupations; rather, people in these jobs sometimes make wrong decisions, which can occur in any occupation.

4. Voting. If Jesus lived in the United States, how would Jesus vote? Would Jesus vote? Would he vote if there were two ungodly candidates? If the choice is between bad and very bad, is it right to choose the bad? Of course, if not voting causes the very bad candidate to win, that option is untenable. In addition, there are other options, too, such as running for office yourself or supporting a third candidate. Does the NT give guidance for voting in government elections?

Since God establishes governments (Rom 13:1), does it matter if a person votes in a democracy or republic? Here are two perspectives. First, that passage may mean God set up government but not particular governments, so Christians should work to set up the best government possible. Second, if that passage refers to particular governments, one must understand how God works throughout history: it is through people. God gave Canaan to the Jewish people, but he did not drop it into their laps. They had to work to conquer it. God desires that we live in godly marriages, but a good marriage takes hard work. It does not instantly happen. Nor does a good government suddenly appear—it takes hard work.49

An extension to rendering unto Caesar would be participating in government practices that do not go against God’s Word. So, if a government allows its citizens to vote, they ought to do so. Former US Solicitor General Ken Starr calls for Christians to vote their faith as well as to run for office—from local school boards and city councils to positions at the state and federal level to make a positive difference in their communities.50

5. Holding office and civil service. Should a Christian hold public office or work in civil service? Here are two NT examples. First, Sergius Paulus, proconsul of Cyprus, was the first named convert on Paul’s first missionary journey (Acts 13:7, 12). He was “an intelligent man” (andri synetō) who presumably held office after his conversion. Sergius possibly sent helpful letters of commendation with Barnabus and Saul as they went to the mainland.51 Second, in the subscription in Romans, Paul mentioned Erastus, “the city treasurer” (ho oikonomos tēs poleōs) who sent greetings (Rom 16:23). This name helps locate Corinth as the city from which Paul wrote Romans. An extant pavement stone just northeast of the theater ruins at Corinth clearly displays the carved name “Erastus.” He paid for this stone and it dates to the middle of the first century. One would assume from what Paul wrote that Erastus was a Christian public servant.

A Christian should live a godly life, exhibit the fruit of the Spirit, and do good works to others in every legal occupation. Not everyone is called to civil service or to hold public office. However, Christians who do serve in those jobs are able to help many people. This can be part of the doing “good” that government should “praise” (1 Pet 2:14).

6. Participating in civil disobedience or revolution. What should a Christian do who lives in an evil empire? The first-century Roman government was pagan, but it was mostly benevolent to Christians except during the reigns of emperors Nero and Domitian. However, it was nothing like the terrible one to come in Revelation. Regardless of one’s interpretive view of Revelation, all must agree that the government in Revelation is evil and works against God. What must Christians do in those situations? Does the NT condone civil disobedience or revolution?

There are NT examples of civil disobedience. Peter, John, and other apostles refused to obey the Sanhedrin’s demand to stop sharing about Jesus (Acts 4:19–20; 5:29–32). No doubt the future persecution of Christians in Revelation (6:9; 12:11; 16:5–6; 17:6; 18:24; 19:2) is from similar situations. Thus, a Christian must disobey an immoral law and be willing to accept the consequences.52 There are no NT examples about revolution; rather, there is a passive acceptance of persecution. Nowhere does the NT explicitly address revolt.53 So, is revolution ever biblically justifiable? A separate study is needed to fully answer this question. Mott posits an interesting view in his requirements for a “just revolution”: (1) there is a just cause, (2) the last resort is revolution, (3) the implementation is by a lawful public authority: a parallel government, (4) there is a sufficient possibility of victory, (5) the probable good outweighs the resulting evil, and (6) it is conducted through proper means, such as excluding torture and terrorist violence against civilians.54

The Christian’s responsibility to work for justice and peace in the world to better spread the gospel message must be balanced with the example one may be called upon to give through nonretaliation and joyful personal suffering under an oppressive government. Yet, there may be times for disobedience and even revolt to protect the lives of others.

III. CONCLUSION

It is fitting that the only appearance in the NT of the noun “citizenship” (Phil 3:20) provides a capstone for what the rest of the NT says about this subject. Paul wrote “our citizenship is in heaven,” referring both to himself, his coworker Timothy, and the Christians at Philippi. Of course, this concept applies to all Christians. Although Paul, and likely some recipients in this garrison city, were Roman citizens, others were not. Yet, they were all were subject to their governing authorities. At the same time, all these believers were citizens of heaven (v. 20).

Every Christian relates to two kingdoms: heavenly and earthly. One must always obey God. His realm is the higher one and it includes everything. One must also obey terrestrial authorities if doing so does not contradict what God says. In citizenship issues not specifically addressed in the NT, such as volunteering at the local library, one should apply the principles of promoting the greater good in society (1 Pet 2:12, 14) and taking every opportunity to be salt and light for Christ in the community (Matt 5:13–16).

One might think it is easy to decide when a government’s practice or law goes against God. Sometimes it is. For instance, any law against Christian evangelism or against a person converting to Christ is wrong, and these are common laws in current Muslim governments. Abortion is the taking of a human life and is wrong. Yet, some current issues divide Christians in the United States—federal immigration policies, actions (or inaction) along the southern border, gun ownership, climate change, federal minimum wage, and a host of other divisive issues.55 One must approach each issue biblically, humbly, carefully, and prayerfully.

- “16 Government Types,” Infographic Facts, accessed November 1, 2021, https://infographicfacts. com/16-government-types/. ↩︎

- “Countries & Areas,” U.S. Department of State, accessed December 1, 2021, https://www.state. gov/countries-areas/. ↩︎

- Although there is much scholarly debate on the matter, this writer assumes the traditional author- ship of the NT. ↩︎

- All NT translations are the author’s own. ↩︎

- Edwin M. Yamauchi and Marvin R. Wilson, Dictionary of Daily Life in Biblical and Post-Biblical

Antiquity (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2017), s.v. “Citizens & Aliens.” ↩︎ - Longenecker says this saying by Jesus may be behind what was later written in Rom 13:7; 1 Pet

2:13–14; and Titus 3:1–2. However, his assertion that it was from a “sayings of Jesus” or “Q collection” is unwarranted. Richard N. Longenecker, The Epistle to the Romans: A Commentary on the Greek Text, NIGTC (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2016), 967–68. See also R. T. France, The Gospel of Matthew, NICNT (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2007), 830–31. ↩︎ - The phrase “tax collectors and sinners” appears nine times in the Gospels—singling out this despised occupation (Matt 9:10–11; 11:19; Mark 2:15–16; Luke 5:30; 7:34; 15:1; 7:34). ↩︎

- Richard Bauckham, The Bible in Politics: How to Read the Bible Politically (Louisville: WJK, 2011), 79. A denarius had the value of one day’s wage for a common day laborer. ↩︎

- Thus, an empire-critical reading that in his answer Jesus promoted rebellion against Rome and giving nothing to Caesar is unwarranted. Contra Richard A. Horsley, “Jesus and Empire,” in In the Shadow of Empire, ed. Richard A. Horsley (Louisville: WJK, 2008), 89, 90, 95. ↩︎

- France, Matthew, 830. ↩︎

- Figure 1 is an adaptation of a helpful illustration by my friend Curtis Broyles, who does not remember the source from many years ago. However, Lenski gives a similar description. “This ‘and’ [v. 21] connects a small field with the whole field…. Our obligations to God are the whole of life, those to the state one part of this whole.” R. C. H. Lenski, The Interpretation of St. Matthew’s Gospel (Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1943), 867. See also Floyd V. Filson, The Gospel According to St. Matthew, BNTC (London: Black, 1960), 235. ↩︎

- It is unwarranted to call the Pharisees and Herodians hypocrites for carrying a denarius on temple property. Nowhere does the biblical text say it was their denarius. They “brought” it to Jesus. Contra France, Matthew, 830. They could have secured a coin from a passerby or from someone outside the temple. However, they were hypocrites in their legalism and for testing Jesus (Matt 22:18). ↩︎

- Josephus mentions this tax in J.W 7.6.6 and Ant. 18.9.1. Interestingly, after the destruction of the Temple in AD 70, Rome continued collecting this religious tax for Jupiter Capitolinus. Early Christians probably also had to pay it since many were Jewish. ↩︎

- Most English Bible translations incorrectly use the term “shekel” to translate the Greek word statēr. ↩︎

- Contra Craig L. Blomberg, Matthew, New American Commentary 22 (Nashville: Broadman, 1992), 271. ↩︎

- See J. Duncan M. Derrett, “Peter’s Penny: Fresh Light on Matthew XVII 24–7,” NovT 6 (1963): 1. ↩︎

- One may assume Paul did not bribe Festus because Paul would have been released had he done so. ↩︎

- F. F. Bruce, Paul: Apostle of the Heart Set Free (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1977), 441–45. Bruce examines the extant extrabiblical material about Paul’s last days and martyrdom. ↩︎

- Michael J. Gorman, Romans: A Theological & Pastoral Commentary (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2022), 252. ↩︎

- Gorman believes “love” in 13:8–10 “supports Christian opposition to many laws and practices” in the US, but he is practicing eisegesis here. Gorman, Romans, 259. ↩︎

- Contra James Kallas, “Romans XIII.1–7: An Interpolation,” NTS 11 (1965): 374. Käsemann is correct in concluding Pauline authorship of this passage by both external and internal proofs. Ernst Käsemann, Commentary on Romans, trans. and ed. Geoffrey W. Bromiley (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1980), 350–52. ↩︎

- Peter Oakes, Empire, Economics, and the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2020), 166. ↩︎

- See Colin G. Kruse, Paul’s Epistle to the Romans, PNTC (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2012), 491–92. ↩︎

- Tacitus wrote about many complaints about Roman indirect taxes (portoria), ad valorem taxes such as custom taxes, in AD 58 (Ann. 13.50). Likely, this anger simmered for years before it came to a head. ↩︎

- Contra Neil Elliott, “The Apostle Paul and Empire,” in In the Shadow of Empire, ed. Richard A. Horsley (Louisville: WJK, 2008), 110. Elliott says this is a puzzling passage and may have an undercurrent of defiance and dissent in his empire-critical interpretation of the text. He rejects using this passage to discern a Christian’s relationship to the state, but his skepticism is unwarranted. This passage fits well with what Paul wrote in 1 Tim 2:1–2 and Titus 3:1–2. ↩︎

- See Oscar Cullman, The State in the New Testament (New York: Scribner’s Sons, 1956), 94-114, where he defends this interpretation against his critics on grounds of philology, Judaistic concepts, and Pauline and early Christian theology. ↩︎

- See Longenecker, Romans, 956-69. ↩︎

- John Howard Yoder, The Politics of Jesus: Vicit Agnus Noster, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans,

1994), 199–202. He describes the views but advocates for the third one. Each view has strengths

and weaknesses. ↩︎ - See the same word for this subject in Titus 3:1 and 1 Pet 2:13. Paul also used this word for

Christians to “submit” to each other in the context of the church (Eph 5:21–22) and for wives

“submit” to their husbands (Col 3:18; Titus 2:5). ↩︎ - Kruse, Romans, 492. ↩︎

- Consider also how God used pagan Assyrians to judge Israel and pagan Babylonians, Medo-

Persians, Greeks, and Romans (in succession) to judge Judah. Yet, here Paul addressed how a government acted toward its citizens. ↩︎ - Robert Jewett, Romans, Hermeneia (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2007), 795. ↩︎

- Kruse, Romans, 496–7; See also James D. G. Dunn, Romans 9–16, WBC 38 (Dallas: Word,

1988), 764. ↩︎ - Thomas M. Coleman, “Binding Obligations in Romans 13:7: A Semantic Field and Social

Context,” TynBul 48.2 (1997): 310. ↩︎ - BDAG, s.v. “telos.” ↩︎

- BDAG, s.v. “phobos.” ↩︎

- Coleman, “Binding Obligations,” 318–27. ↩︎

- James Leo Garrett Jr., “The Dialectic of Romans 13:1–7 and Revelation 13: Part One,” Journal of Church and State 18 (1976): 441. ↩︎

- Although there are some nuanced differences in the first three nouns, Paul was likely “collecting synonyms that effectively communicate the importance of prayer.” Thomas D. Lea, “1 Timothy,” in 1, 2 Timothy, Titus, NAC 34 (Nashville: B & H, 1992), 81. One might argue these epistles are irrelevant to this study because Paul wrote them to individuals. However, there is evidence Paul intended them for the church also. For instance, neither Timothy nor Titus needed to be reminded Paul was “an apostle of Jesus Christ” (1 Tim 1:1; 2 Tim 1:1; Titus 1:1) or that they were converts under Paul’s ministry—the likely meaning of being Paul’s “true child in the faith” (1 Tim 1:2; Titus 1:4). Yet, those local churches did need this information. ↩︎

- See early mention of prayer for rulers in Ezra 7:25–28; 9:5–9; Josephus, Ant. 13.5.8; and Justin, 1 Apol. 17. ↩︎

- This word appears only four times in the NT and only once in Paul’s letters. The more common word for “obey” is hypakouō, appearing twenty-one times in the NT (eleven times in Paul). Hendriksen weds these terms well: Christians must outwardly subject themselves and inwardly have willful obedience. He adds that this applies if the commands do not conflict with obedience to God. William Hendriksen, 1–2 Timothy, and Titus (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1979), 386. ↩︎

- Karen H. Jobes, 1 Peter, BECNT (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2005), 175–76. ↩︎

- Wayne A. Grudem, I Peter, TNTC (Downers Grove: IVP, 1988), 184. ↩︎

- The two dominant views are Idealist and Futurist. Idealists say no specific government is in view

and these are symbols of ongoing struggles. Most Futurists, such as this writer, believe there will be a specific future evil empire. ↩︎ - Christians are competent to judge civil matters. In some way Christians will be used in the final judgment of the world (1 Cor 6:2), which will include judging angels (6:3). These must be fallen angels, demons (see Rev 19:19–20; 20:10). ↩︎

- This writer has heard these examples from fellow Christians many times through the years. ↩︎

- One might object to signing a church pledge card for personal reasons, but citing Jesus’s prohibition of oath giving is not a biblical reason. ↩︎

- This was illegal because Paul was a Roman citizen. Paul had them apologize the next day for doing this—probably to make it clear he and Silas did not break any Roman law (Acts 16:37–39). ↩︎

- See Robert Tracy McKenzie, We the Fallen People: The Founders and Future of American

Democracy (Downers Grove: IVP, 2021). ↩︎ - Ken Starr, Religious Liberty in Crisis: Exercising Your Faith in an Age of Uncertainty (New York: Encounter, 2021), 171. He focuses on what he calls the Great Principles of liberty and equality under the law that “form the foundation of so much of our legal system” (35) and are principles within our constitution that are founded on Scripture. See also p. 70. He mentions additional Great Principles of “church autonomy, freedom of conscience, accommodation of religious belief and practice, and the primacy of history and tradition triumphing over [judge-made] doctrine” (146). ↩︎

- Davis proposes this scenario. Thomas W. Davis, “The Destination of Paul’s First Journey: Asia Minor or Africa?” Pharos Journal of Theology 97 (2016): 3. ↩︎

- See Mott’s five criteria to follow for civil disobedience to lead to social change. Stephen Charles Mott, Biblical Ethics and Social Change, 2nd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 138–41. ↩︎

- This is contrary to empire-critical studies which claim many NT passages give a coded message to revolt against the evil Roman Empire. For instance, Horsley says Jesus’s exorcisms are symbols for the expulsion of the Roman occupying forces. Horsley, “Jesus and Empire,” 86. ↩︎

- Mott, Biblical Ethics and Social Change, 160–62. ↩︎

- For a somewhat balanced treatment of these issues, see Daniel K. Williams, The Politics of the Cross: A Christian Alternative to Partisanship (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2021). ↩︎