Christian Higher Education in the Baptist Tradition

Southwestern Journal of Theology

Volume 62, No. 2 – Spring 2020

Editor: David S. Dockery

Baptist higher education in the twenty-first century must continue to carry out the essential task commissioned by the risen Christ (Matt 28:19–20). Baptist education in North America, and particularly among Southern Baptists since the middle of the nineteenth century, has attempted to be academically sound, Christ-centered, grounded in the Scriptures, and connected to and with the churches. Throughout these years, one can observe both continuities and discontinuities as Baptist educators have simultaneously demonstrated both the courage to lead and a listening ear to respond to the churches, for Baptist higher education is indeed a two-way street.1

Our look at Baptist higher education in this article will include both the work of colleges and universities, as well as theological seminaries. We will provide a brief reminder and overview of Christian higher education prior to the nineteenth century before taking a more focused view of education in Baptist life. Doing so will help us be able to observe markers of continuity prior to the modern period.

I. CONTINUITIES IN CHRISTIAN EDUCATION: FROM THE APOSTLES TO THE BEGINNING OF NORTH AMERICAN EDUCATION

1. Apostolic and Postapostolic Period. The student of history can discern little difference between the theological preparation provided for church members and that designed for church leaders in the apostolic and postapostolic periods.2 People were called to ongoing study (2 Tim 2:15) in order to provide oversight for the ministry of the Word of God in the midst of worship services, as well as to mentor and disciple new converts (2 Tim 2:2; Titus 1:9).

The apostle Paul, writing to the church at Thessalonica, urged followers of Jesus Christ to “stand firm and hold to the traditions you were taught” (2 Thess 2:15). Similarly, the apostle exhorted Timothy, his apostolic legate, to “hold on to the pattern of sound teaching” (2 Tim 1:13). The history of Christian education is best understood as a chain of memory with succeeding generations building on that which has gone before them.3

Wherever the Christian faith has been found, there has been close association with the written Word of God, with books, education, and learning. Studying and interpreting the Bible became a pattern for members of the early Christian community, having inherited the practice from late Judaism.4 The tradition that would eventually shape more formal approaches to both Christian higher education and to theological education locates its roots in the interpretation of Holy Scripture.

Beginning in the second century, the serious study of the Bible started to inform the early stages of theological education in the church, which was shaped by a shared faith in the uniqueness and significance of Jesus of Nazareth. Formal training by the time of the second century, during the time of Justin Martyr (100–165), Irenaeus (125–202), and Tertullian (150–225), tended to focus on areas of philosophy and rhetoric.5 The authority of the church, affirmations regarding the biblical canon, and efforts toward theological formation had reached new heights by the beginning of the third century, which saw the rise of schools, intertwined with classical learning, science, philosophy, and centers of art. Steps toward serious educational engagement began to develop and mature in the schools of Alexandria and Antioch.6

Athanasius (296–371), more than anyone else during the fourth century, shaped the church’s understanding of the expanding rule of faith, which became the framework for theological understanding and catechesis. The consistent articulation of the church’s orthodox faith, coupled with pastoral concerns for the edification of the faithful, provided norms for the shaping and advancement of the work of educational instruction.7

2. Augustine and the Medieval Period. The most important and influential shaper of theology and education during the first thousand years of church history was Augustine (351–430), who paved the way for future theologians and educators. Some have even suggested that the past fifteen hundred years are best understood as a footnote to the work of Augustine.8

Justo Gonzalez has noted that during this time the practice also arose of employing monastic life as an opportunity to study. The monastic schools began to occupy a central place in European intellectual life as well as for those preparing for ministry. While serious educational advances took place during this time, we must recognize that there were still no formal academic institutions. Personal mentoring, guidance, and teaching from pastors and bishops, including Augustine himself, remained the primary model for theological education.9 During the medieval period, educational efforts were expanded and strengthened through the efforts of Anselm (1033–1109), Bernard of Clairvaux (1090–1153), and Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274).10

The students of these outstanding thinkers for the most part became pastors, but these teachers of the church did not perceive of their role as primarily preparing people for ministry. In seeking to prioritize and advance the Christian intellectual tradition, they helped provide a prominent place for the developing universities birthed during these years. While early Christian education emphasized catechetical purposes, medieval universities were largely shaped for the purposes of professional education, with some general education for the elite. Of the seventy-nine universities in existence in Europe during this time, Salerno was best known for medicine, Bologna for law, and Paris for theology.11 Thus the aim of most medieval universities was not focused on ministerial education so much as philosophical and contemplative inquiries.12

Nowhere was this kind of serious Christian engagement better seen in the medieval context than in the work of Thomas Aquinas. He and other medieval thinkers flourished in a context in which the Christian faith provided illumination for the intellectual landscape and the central mission of the university generally focused on inquiry in pursuit of truth. Faith in the context of medieval Christendom was understood to be an ally, not an enemy, of reason and intellectual exploration. Since the medieval period, Christian universities, which arose ex corde ecclesiae or “from the heart of the church,” have been one of the primary places where the Christian faith has been advanced and from which formal ministerial education began to take shape.13

3. Renaissance and Reformation. The Renaissance envisioned the revival of Greek and Roman literature while newer subjects were developing during the medieval periods such as arithmetic, geometry, and music. The Reformation period placed education within the context of a Christian worldview. While Martin Luther (1483–1546) is widely recognized as the father of the Reformation, in reality he, in many ways, carried forward the work of Peter Waldo (1140–1218), John Wycliffe (1330–1384), Jon Hus (1373–1415), Girolamo Savonarola (1452–1498), and even Desiderius Erasmus (1466–1536). All of these prioritized the Scriptures in bold ways, but Erasmus (even more so than Luther), through the influence of John Colet (1466–1519), rediscovered the priority of the historical sense of biblical interpretation.14 As significant and innovative as the work of Erasmus was, the pivotal and shaping figures of the Reformation were Martin Luther and John Calvin (1509–1564).

Luther, reclaiming the key aspects of the Augustinian tradition, also insisted that the human intellect adjust itself to the teachings of Holy Scripture. Luther’s bold advances have influenced Christian thinkers and the works of theological education for five centuries, yet John Calvin in a sense “Out-Luthered” Luther to shape aspects of the Christian intellectual tradition that have developed since the sixteenth century.15 John Calvin was the finest interpreter of Scripture and the most precise Christian thinker of this period.16 Yet, it was Philip Melanchthon (1497–1560) more than anyone else during the Reformation period who advanced important educational initiatives. Melanchthon’s Loci Communes (1521), the first systematic expression of Lutheran ideas, gained widespread influence due to its clear and irenic approach. He helped to reform eight universities and to found four others, while penning numerous textbooks for use in various schools, acade- mies, and institutions. These things earned him the title of “Preceptor of Germany.”

Luther’s colleague proposed a new theological curriculum from which came the threefold shape of theological education: (1) the study of the Bible and its interpretation, (2) the study of doctrinal theology, and (3) the application of these subjects with special attention to the practical administration of churches, preaching, worshipping, and ministry. Formal theological education became a requirement for ministerial ordination during the sixteenth century, a practice that has continued to be the expectation in many traditions up to the present day.17

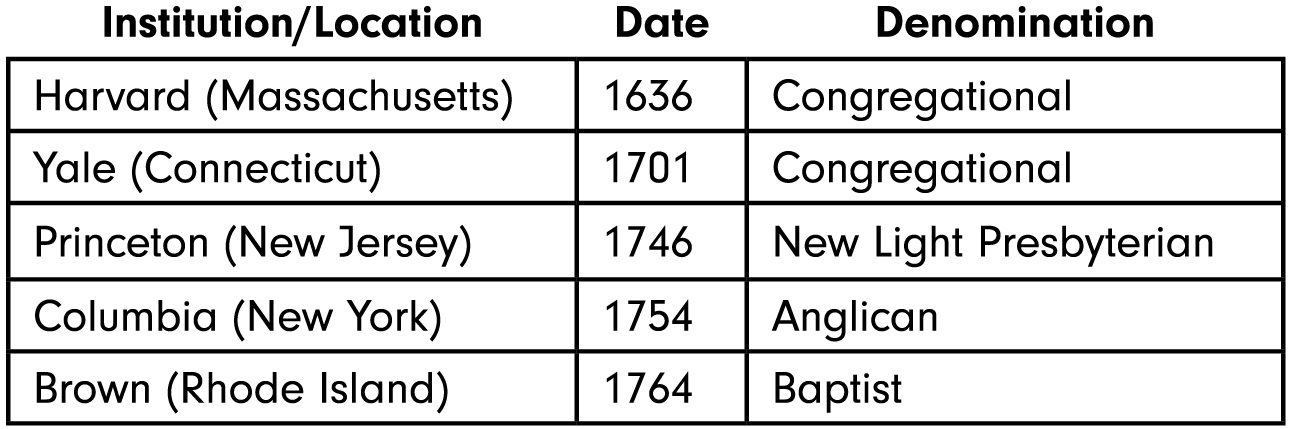

By the seventeenth century, these streams proliferated, resulting in both fragmentation and greater variety of the expressions of the Christian movement.18 Many aspects of this expansion were good and helpful as the Christian message began to circle the globe. It was during this time that early American colleges were formed, governed by trustees from related Christian denominations. These institutions provided education within the context of faith and were grounded in the pursuit of truth for Christ and his church. Some of these schools included:

Rhode Island was the ideal place to launch a Baptist institution in the middle of the eighteenth century, for this American colony had more Baptists than any other. While these early Baptists were not necessarily zealous for the cause of education, even for the preparation of their ministers, they still wanted their own institution rather than sending their best and brightest to Harvard or Yale. For as Leon McBeth observed, experience had taught them that “you could send a Baptist to Harvard, but you could not get one out.”19 Donald Schmeltekopf and Dianna Vitanza have provided us with a detailed look at the history of Baptist higher education in this country in their volume on The Future of Baptist Higher Education.20

At this point, we will turn our attention to an exploration of continuities and discontinuities in Baptist higher education, with a focus on Southern Baptist higher education, realizing that the streams that influenced the practice and shape of Christian education during the church’s initial eighteen centuries provided the framework for education in Baptist life. We will seek to conclude with a look at hopeful trajectories related to this movement.

II. DISCONTINUITIES IN BAPTIST HIGHER EDUCATION

Baptists have been involved in higher education in America for more than 250 years. Brown University, the first Baptist institution established in this country, is now one of the premier Ivy League institutions. Brown rarely thinks of itself as having a Baptist identity or heritage, and unfortunately, this story can be told over and over again. The second Baptist institution in this country was Colby College (1813), a very fine institution in Maine for many years. Today, Colby is recognized as one of the top liberal arts colleges in the United States, but it no longer identifies itself as connected to Baptist life. Colgate was an institution founded in the state of New York by the Baptist Society of Education in 1819, but hardly anything at Colgate University still resembles a connection to its Baptist heritage. Understanding these developments provides contemporary distinctive Baptist institutions with a sober warning about the need to carry on a distinctive Baptist mission in a faithful manner. The list of former Baptist institutions who are no longer connected to Baptist life, sadly, is quite long. We must ask, how has this change taken place? At least three major factors can be identified.

1. Enlightenment and Post-Enlightenment Thought. The first of these is the influence of Enlightenment and post-Enlightenment thought, which challenged the very heart of the Christian faith by raising questions about authority, tradition, and the role of reason. The Enlightenment, which blossomed in the eighteenth century, was a watershed in the history of Western civilization. The Christian consensus that had existed from the fourth through the seventeenth centuries was hampered, if not broken, by a radical secular spirit. Enlightenment philosophy could be characterized by its stress on the primacy of nature and reason over special revelation. Along with this elevated view of reason, the movement reflected a low view of sin, an anti-supernatural bias, and an ongoing questioning of the place of authority and tradition.21

Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768–1834) led the way with his efforts to attempt to synthesize the Christian faith with Enlightenment ideas. His work, best seen in On Religion: Speeches to Its Cultured Despisers (1799) and Brief Outline of Theological Studies (1811), transformed the Christian faith into something quite different, evidencing observable discontinuity with Luther, Melanchthon, and Calvin. Schleiermacher initiated a trajectory that emphasized critical studies, which, contrary to Schleiermacher’s intention, tended to separate the study of the Bible and theology from the life of the church and create tensions between the head and heart, as well as between academy and congregations.

2. Academic Specialization. A second contributing factor involved the rise of academic specializations in all aspects of higher education. Christian higher education was not exempt from this development, particularly the implications of this shift in higher education offerings, which began around 1870 and greatly expanded throughout the twentieth century. At the heart of faithful Christian higher education can be found the belief that all knowledge, all truth, and all wisdom have their source in God. From this commitment, Christian educators have insisted on the unity of knowledge. Disciplinary specialization not only emphasized one academic discipline above others but suggested that a particular way of knowing was also distinctive to each discipline. This disciplinary specialization, when recognized as the dominant metanarrative for higher education, began to dismantle the coherence of the curriculum while disconnecting the presuppositional connection between the Christian faith and academic knowledge that had previously existed on both public and private cam- puses. Built on the framework of a Christian worldview, Christian higher education maintained a unity of knowledge from subject to subject. As James Turner has observed:

This assumption flowed from the elemental Christian beliefs: a single Omnipotent and all-wise God had created the universe, including human beings, who shared to some extent in the rationality behind creation. Given this creation story, it followed that knowledge, too, comprised a single whole, even if finite and fallible human beings could not perceive the connections clearly or immediately. And Christianity generated an intellectual aspiration, even imposed a duty, to grasp the connections, to understand how the parts of creation fitted together and related to divine intention.22

Together with the loss of the capstone course in moral philosophy, which had been characteristically taught by theologian-presidents such as Timothy Dwight at Yale, and the rise of philological historicism, which bracketed the pursuit of knowledge and truth in the humanities, combined with the influence of methodological naturalism in the sciences, the rise of disciplinary specialization severed the coherent approach to knowledge that had shaped so much of higher education in North America in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.23 Unfortunately, most of these changes unknowingly took place on Baptist college campuses because Baptist higher education largely focused on providing education within a healthy moral context without a full-orbed philosophy of education,24 thus separating faith and learning into two separate spheres. Academic offerings, without the anchors of Christian worldview commitments, soon appeared quite similar to the subject matter taught in more secular contexts.

3. Loss of Relationship with the Churches. The third contributing factor in this overall development had to do with the loss of connection with the churches. The disconnect from the churches also included an accompanying separation from the Christian intellectual tradition and the church’s confessional heritage as well. A piece of this complex issue involved the disassociation of free-standing seminaries from the colleges and universities, opening the door for the dynamics associated with secularization, implications not intended by those who helped to birth Southern Seminary out of the Furman University community (and the same could be said for B. H. Carroll and the launch of Southwestern Seminary from within the context of Baylor University). One cannot overstate that Baptist colleges and universities are decidedly not churches, yet they must remain connected with the churches to carry out their mission in a faithful manner over the long term.25

James Burtchaell, in his massive study The Dying of the Light, surveyed dozens of institutions from various traditions, including the Baptist tradition. His important work brings to the forefront the reality of how many institutions from various traditions have seen the light of the Christian faith die out on their campuses. Burtchaell may well have been wrong about some of the particulars in his research, but his big picture thesis generally holds true across the various traditions and across the decades. The moment an institution begins to lose its connection with the churches is the day the light starts to disappear on the campus. Baptist institutions, while not churches, are an extension of the churches, the academic arm of the kingdom of God. High quality teaching and scholarship can be done and must be done without neglecting the relationship with the churches.26

Today, the landscape of Baptist higher education institutions presents a varied picture, not only because of these major shifts in the world of Baptist higher education, which must be understood within the big picture of higher education in general in North America, but also due to the different Baptist traditions that influenced aspects of Baptist higher education. Many Baptist historians talk about these various shaping traditions, whether “the Charleston tradition,” “the Sandy Creek tradition,” “the Landmarkist tradition,” or the “frontier tradition.”27 It is the Charleston tradition in which we find the strongest commitment to education and a corresponding commitment to serious scholarship informed by a confessional heritage.

Beyond these various geographical trajectories, a number of other elements have influenced the varied shape of Baptist higher education as we know it today. The influence of Princeton Seminary in the nineteenth century cannot be discounted. It was at Princeton that James Boyce and Basil Manly Jr., who influenced both Furman University and the founding of Southern Seminary, were educated. The pietistic revivalism of the frontier influenced Texas institutions, particularly Baylor University and Southwestern Seminary. The Particular Baptist and General Baptist differences, including emphases on the importance of a theological confessional framework and the place of religious experiences, have also contributed to the diversity of perspectives. Over the past 75 years, questions concerning headways into Southern Baptist life by liberal European theology on the one hand and the influence of North American evangelicalism on the other have pulled Baptists in two different directions, while the presence of an anti-intellectual fundamentalism has tended to raise suspicion about all aspects of the Baptist education project. All of these things, to one degree or another, have influenced at least an aspect of Southern Baptist life in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries and the works of Baptist higher education in particular. In so many ways, Southern Baptist-related higher education reflects the synergistic confluence of these factors.28

4. Understanding Baptist Distinctives. Southern Baptists share many similarities with other North American Christians. We can identify at least four: (1) the Baptist heritage is formed by orthodox Christian convictions; (2) Baptists are influenced by the larger evangelical tradition; (3) Baptists are heirs of the sixteenth-century Reformation (with influence also from the “radical reformers”); and (4) Baptists share connections with the great historic Christian confessions. With these four overarching markers, Baptists relate to other Christians and Christian traditions.29

Distinctive Baptist markers include: (1) believer’s baptism instead of infant baptism; (2) voluntary ecclesiology based on a regenerate church membership instead of an inherited/parish ecclesiology; (3) local organization of church life instead of state control, with its implications for religious liberty; (4) biblical authority as priority over tradition; (5) populist biblical interpretation growing out of shared belief in the priesthood of all believers rather than the authoritative teaching of bishops; (6) Christian ordinances of baptism and the Lord’s Supper practiced primarily as matters of obedience rather than as a means of salvific grace; and (7) a commitment to religious liberty.30

These influences and distinctive markers have shaped Southern Baptist education. From these influences have also arisen challenges to Southern Baptist higher education, some of which have helped to push Baptist institutions away from their relationship with the churches. Matters such as localism, Landmarkism, an a-theological pietism, populism, as well as the presence of theological liberalism on the one hand and fundamentalism on the other, have tended to stifle sanctified intellectual development, or at least have made it nearly impossible to claim a shared consensus. In addition, these trajectories have failed to appreciate the importance and breadth of the Christian intellectual tradition, thus often disconnecting Baptist educational efforts from the continuity and sense of catholicity found in the first eighteen centuries.

Those seeking to carry forward faithful Baptist higher education will need to be aware of these potential pitfalls, learning from history while strengthening and renewing foundational confessional commitments. Our Baptist forbearers recognized the importance of such commitments. In 1905, when E. Y. Mullins (1860–1928) and A. T. Robertson (1863–1934) led Baptists on both sides of the Atlantic to come together with Baptists from other parts of the world to think globally and confessionally about Baptist work, they acknowledged that the starting place for doing so was with a common confessional commitment as they stood together as one to recite in unison the Apostles’ Creed.31 It must be acknowledged, however, that W. O. Carver (1868-1954), professor of world religions and missions at Southern Seminary, W. L. Poteat (1856-1938), president and professor of biology at Wake Forest, Samuel Brooks (1863-1931), president at Baylor, and other important Baptist thinkers and leaders of the twentieth century were less than excited about such confessional commitments, particularly with application to Baptist higher education at the time when Southern Baptists led by Mullins and L. R. Scarborough (1870-1945) adopted their first convention-wide confession of faith at the annual convention in Memphis in 1925.32

As we think about moving beyond the various continuities and discontinuities of the past with a view toward a renewed vision for Baptist higher education, we believe that a confessional foundation will serve well to advance such a distinctive approach. We can begin with the Apostles’ Creed, and from there we can begin to cultivate a holistic orthodoxy based on a high view of Scripture that is congruent with the great affirmations of the Early Church regarding Jesus Christ and the Holy Trinity. By reconnecting with the great consensus fidei, the great confessional tradition of the church, we can seek to avoid the errors of fundamentalist reductionism on the one hand and liberal revisionism on the other.

III. TOWARD A RENEWED VISION AND HOPEFUL TRAJECTORIES FOR BAPTIST HIGHER EDUCATION

Baptist higher education blossomed in the middle of the twentieth century as new institutions were established and other more mature enti- ties moved into phases of expansion and growth. Important for these efforts was the work of the Education Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention, which existed in various forms from 1917 to 1996. Leadership for this effort was carried out by Charles Johnson, R. L. Brantley, Orin Cornett, Ben Fisher, and Arthur Walker, among others.

In 1928, the purpose of the Commission was clearly articulated as follows:

The duties of the Commission shall be to stimulate and nurture interest in Christian education, to create educa- tional convictions, and to strive for the development of an educational conscience among Baptist people. In short, this Commission shall be both eyes and mouth for Southern Baptists in all matters pertaining to education.33

For a number of reasons, the Education Commission came to an end in 1996 during the restructuring of the SBC in the mid-1990s. The closing of the Commission brought closure to the organizational consensus among Baptist educators and Baptist educational entities, though it must be acknowledged that there existed minimal consensus regarding the essence and overall purpose of Baptist higher education.34 In the final section of this article, we would like to propose a vision for the renewal of Baptist higher education as we move together into the middle decades of the twenty-first century.

1. Toward a New Consensus. Baptist educational leaders have been entrusted with the Christian faith, the body of truth once for all delivered to the saints (Titus 1:9; Jude 3). We recognize that the Christian faith is not merely some personal, subjective, amorphous feeling. While personal faith in Christ and genuine piety are essential, an understanding of the Christian faith must include what H. E. W. Turner (1907–1995) called “the pattern of Christian truth.”35 One of the first building blocks in the shaping of a new consensus will include shared affirmations regarding the Trinitarian God (Father, Son, and Holy Spirit), Scripture, humanity, sin, salvation, the Christian life, the church, the kingdom of God, eternal life, as well as important commitments in the area of Christian ethics. Such an approach recognizes that Baptist higher education is best done in, with, and for the church.

In 1996, William Hull (1930–2013), who at the time served as provost at Samford University, noted in his Hester Lecture that:

clearly this is a critical time to redefine the meaning and mission of Christian higher education, and to understand the distinctive reason for our existence. … Our need now is not for a general philosophy of education, but for an explicit theology of education rooted in the imperatives of the Christian gospel. In a time of spiritual confusion and moral anarchy, Baptists have been driven back to the Bible and to their core confessions of faith, which is where the church always goes when under furious attack.36

In many ways this proposal extends my own personal engagement with Provost Hull, who passed away in 2013.37 In the midst of what Hull referred to as this “secular and empty age,” we offer a proposal that seeks to describe the heart of distinctive Baptist higher education.

A look around the globe points to a shift among the nations that will influence the world for decades to come. We must keep our eyes on cultural and global trends since our work never takes place in a vacuum, and this observation does not begin to address the changes in higher education itself in terms of focus, funding, philosophy, methodology, and delivery systems, much less the changes that will be forthcoming in our post-COVID context.

2. A Theological and Confessional Framework. Baptist higher education involves a distinctive way of thinking about teaching, learning, scholarship, subject matter, student life, administration, and governance that is grounded in the orthodox Christian faith. The Christian faith not only influences our devotional lives and our understanding of piety and spirituality, as important as these things are, but it shapes and informs what we believe, how we think, how we teach, how we learn, how we write, how we lead, how we govern, and how we treat one another.38 As Hull noted, we need an explicit theological vision to sustain Baptist higher education as we move forward. One thing that has led to the discontinuities within Baptist higher education and loss of distinctive Baptist institutions has been the lack of a theological vision to sustain them and to serve as an anchor and compass for the work.39

While at some of these institutions one can still find remnants of a theology or religion department, there is often confusion as to whether these programs belong to the areas of history or philosophy or with some other program such as sociology or the fine arts.40 Stanley Hauerwas, the longtime professor at Duke Divinity School, has sadly observed that the loss of theological vision at these places and others means that few Christian institutions will leave behind “ruins,” the kind of material evidence of a vibrant Christian academic culture that glorified God, served the church, and influenced generation after generation of students.41 It is our hope that a more full-orbed understanding of a theologically shaped vision for Baptist higher education will help us to engage the culture and to prepare a generation of leaders who can effectively serve both church and society.

We believe that an understanding of the self-revealing God who created humans in his image provides a beginning point for this vision. We believe that students created in the image of God are designed to discover truth and that the exploration of truth is possible because the universe, as created by the Trinitarian God, is intelligible. These beliefs are held together by our understanding that the unity of knowledge is grounded in Jesus Christ, in whom all things hold together (Col 1:17). The Christian faith then provides the lenses to see the world, recognizing that faith seeks to understand every dimension of life under the lordship of Christ.

The richness of the Christian tradition can provide guidance for the complex challenges facing Christian higher education at this time. At the heart of this work is the need to prepare a generation of Christians to think Christianly, to engage the academy and the culture, to serve society, and to renew the connection with the churches and their mission. To do so, the breadth and the depth of the Christian tradition must be reclaimed, revitalized, and revived for the good of Baptist higher education.42

When we contend that Baptist higher education must be intentionally Christ-centered education, we are in effect confessing that Jesus Christ, who was eternally the second person of the Trinity and shared all the divine attributes, became fully human.43 To think of Christ-centeredness only in terms of piety or activism will not be enough to respond to the challenges of today’s academy and culture.

A healthy future for Christian higher education must return to the past with the full affirmation that we see the whole man Jesus and confess that he is God when we point to Jesus. This is the great mystery of godliness—God manifested in the flesh (1 Tim 3:16). Any attempt to envision a faithful Baptist higher education for the days ahead that is not tightly tethered to the great confessional tradition will likely result in an educational model without a compass.44 The only way to counter the secular assumptions45 that shape so many sectors of higher education today is to confess that the exalted Christ, who spoke the world into being by his powerful word, is the providential sustainer of all of life (Col 1:15-17; Heb 1:2).46

As we seek to bring the Christian faith to bear on the teaching and learning process in the work of Baptist higher education, our approach must involve bringing these truths about Jesus Christ to bear on the great ideas of history as well as on the cultural and educational issues of our day.47 In doing so, our aim will be to adjust the cultural assumptions of our post-Christian context in light of God’s eternal truth. We therefore want to call for the future work of higher education to take place through the lenses of the confessional tradition that affirms a belief in the Holy Trinity, but also recognizes the transcendent, creating, sustaining, and self-disclosing Trinitarian God who has made humans in his image.48

3. Relationship to the Churches. A renewed vision for Baptist higher education must not only connect with the best of the Christian intellectual tradition and our confessional heritage but must also seek a purposeful connection with faithful Baptist congregations. We must once again connect Baptist institutions with the heart of the church. One aspect of this commitment will involve rethinking the primary focus of our theological efforts. It is important that we engage in both academic theology and public theology. At the same time, we acknowledge that our primary focus must recapture a commitment to doing theology for the church.49 Our dream calls for Baptist colleges, universities, and seminaries to be not only Christ-centered and confessionally focused, but also church-connected. This multi-faceted awareness will help us avoid confusing what is merely a momentary expression from that which is of enduring importance for the sake of the churches, enabling us to avoid the tyranny of immediatism.

4. The Place of Academic Freedom. The places of dissent and religious liberty have been significant markers for Baptists over the past 400 years. What do these distinctives have to do with academic freedom in the context of Baptist higher education? One way of sorting through these issues will be to navigate our understanding of primary, secondary, and tertiary matters. In the essentials of the Christian faith, there is no place for compromise. Faith and truth are primary issues, and we stand firm in those areas. Sometimes, however, Baptists have confused issues of primary and secondary importance. In secondary and tertiary matters, we need love and grace as we learn to disagree agreeably. We want to learn to love one another despite differences and to learn from those with whom we differ.

In essentials, faith and truth are primary, and we may not appeal to love or grace as an excuse to deny any essential aspect of the Christian faith.50 When we center the work of Baptist higher education on the person and work of the Lord Jesus Christ, we will build on the ultimate foundation. As we have previously noted, we also need to connect with the great Christian intellectual tradition of the church, which can provide illumination, insight, and guidance regarding these issues.

Our challenge is to preserve and pass on the Christian tradition while encouraging serious and honest intellectual inquiry. There is no place for anti-intellectualism on Baptist campuses. Baptist higher education should be academically rigorous and grounded in the confessional tradition while seeking to understand the great ideas of history and the pressing issues of our day. We pray that Baptist institutions will be places where serious reflection will take place about how to advance these essential Christian commitments while engaging the challenging issues of the twenty-first century.51

Therefore, we recognize the place of academic freedom within a confessional context.52 We encourage exploration across the disciplines while recognizing that some things may not be advocated within the commitments that bind us together as Baptist educational communities. Let us encourage genuine exploration and serious research while acknowledging that free inquiry, untethered from tradition or from the church, often results in the unbelieving skepticism that characterizes so much of higher education today. The directionless state that can be seen as we look across so much of higher education is often found among many former church-related institutions that have become disconnected from the churches and their heritage. We need a renewed vision for Baptist higher education that will help us develop unifying principles for Christian thinking, founded on the tenet that all truth and all knowledge have their source in God, our Creator and Redeemer.53

As we do so, we will continue to struggle with many issues because there are numerous matters that remain ambiguous, matters on which we still see through a glass darkly. Some questions may have to remain unanswered for the short term as we continue to wrestle and struggle together. Yet, we envision a distinctive approach for Baptist higher education, an approach significantly different from the large majority of higher education institutions in North America.

5. Taking the Next Steps. We thus dream of Baptist campuses that are faithful to the lordship of Jesus Christ, that exemplify the Great Commandment, that seek justice, mercy, and love, that demonstrate responsible freedom, and that prioritize worship and service as central to all pursuits in life.54 These institutions must seek to build grace-filled communities that emphasize love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control55 as virtues needed to create a faithful and caring Christian context in which undergraduate and graduate education, grounded in the conviction that all truth has its source in God, can be offered. In sum, we trust for a new generation of leaders for Baptist higher education institutions who will promote confessional convictions, academic excellence, and character development that honors Christ and serves both church and society.

A commitment to rigorous and quality academics is best demonstrated by God-called faculty. While research should be encouraged in all fields, classroom teaching must be prioritized and emphasized. Faculty in all disciplines should be encouraged to explore how the truth of the Christian faith bears on all subject matter. Thus, Baptist higher education institutions cannot be content merely to display their Christian commitments with chapel services, mission trips, and required Bible classes, as important as these activities may be. We desire to see students move toward a mature reflection of what the Christian faith means for every field of study. In doing so, we will see the development of grace-filled, convictional communities of learning.

Because we can think, relate, and communicate in understandable ways, since we are created in the image of God, we can creatively teach, learn, explore, and carry on research. We want to encourage a complementary, and even necessary, place for both teaching and scholarship. A Baptist institution, in common with other institutions of higher learning, must surely subordinate all other endeavors to the improvement of the mind in pursuit of truth. Yet, a focus on the mind and the mastery of content, though primary, is not enough. We believe that character and faith development are equally important, in addition to guidance in professional competencies. Furthermore, we maintain that the pursuit of truth is best undertaken within a community of learning that includes colleagues of the present and voices from the past, the communion of saints, and that also attends to the moral, spiritual, physical, and social development of its students following the pattern of Jesus, who himself increased in wisdom and stature and in favor with God and humankind (Luke 2:52).

As we envision faithful Christian academic communities, we dream of promoting genuine Christian community and unity on our campuses. We appeal for a oneness that is founded on the person and work of Jesus Christ and the common salvation we share in him. One of the ways that we authenticate the message of the gospel and our shared and collaborative work in Christian higher education is the way Christians love each other and live and serve together in harmony. It is this witness that our Lord wants and expects from us in the world so that the world may believe that the Father has sent the Son to be the Savior of the world.

We pray that our twenty-first century context will once again recognize the importance of serious Christian thinking as necessary and appropriate for the well-being of Baptist academic communities. We believe that efforts to reconnect with the best of the Christian intellectual tradition, aspects of which are reflected in the continuities described in the first part of this article, will serve Baptist higher education well in the days ahead as a guide to truth, to that which is imaginatively compelling, emotionally engaging, aesthetically enhancing, and personally liberating. We believe that the Christian faith, informed by scriptural interpretation, theology, philosophy, and history, has bearing on every subject and academic discipline. While at times the Christian’s research in any field might follow similar paths and methods as secular scholars, we believe that doxology at both the beginning and ending of one’s teaching and research distinguishes the works of believers from that of secularists.56

The pursuit of the greater glory of God remains rooted in a Christian worldview in which God can be encountered in the search for truth in every discipline, a frame of reference affirming the importance of the unity of knowledge.57 The application of the great Christian tradition will encourage members of Baptist higher education communities to see their teaching, research study, student formation, administrative service, and trustee oversight within the framework of the gospel of Jesus Christ. In those contexts, faithful Christian scholars will view their teaching and their scholarship as contributing to the advancement of a distinctive mission. Faculty, staff, and students will work together to enhance a love for learning that encourages a life of worship and service. We trust that this proposal will help Baptist educators better see the relationship between the Christian faith and the role of reason, while encouraging Christ-followers to seek truth and engage the culture, with a view toward strengthening the church and advancing the kingdom of God.58

We believe the time is right to reconsider afresh this vision because of the challenges and disorder across the academic spectrum. The reality of the fallen world in which we live is magnified for us in day-to-day life through global pandemics, broken families, sexual confusion, conflicts between nations, social injustices, and the racial and ethnic prejudice we observe all around us.59

This proposal is rooted in the conviction that God, the source of all truth, has revealed himself fully in Jesus Christ (John 1:14,18), and it is in our belief in the union of the divine and human in Jesus Christ that the unity of truth will ultimately be seen. What is needed is a renewed understanding and appreciation of the depth and breadth of the Christian intellectual tradition, with its commitments to the church’s historic confession of the Trinitarian God, and a recognition of the world and all subject matter as fully understandable only in relation to this Trinitarian God.60 While this approach to Baptist higher education values and prioritizes the life of the mind, it is also a holistic call for the engagement of head, heart, and hands.

We offer this proposal forty years on the other side of the beginning of “the controversy” in Southern Baptist life known as the Conservative Resurgence. Much has changed in Baptist life over the past four decades. People reading this article will, without doubt, have different responses to these changes. Many remain saddened by these developments, now seeing the Southern Baptist world, which they once called “home,” as a rather different place. Others will give genuine thanks for many of the changes, particularly the recovery of a clear understanding of the gospel message and renewed commitment to the truthfulness of Scripture. Still, those serving across the broad spectrum of Baptist-related higher education contexts must recognize that in the midst of these changes we all have been formed, shaped, and influenced by the larger Baptist story.61 We share a common history and heritage from 1609 to 1979, particularly from 1814 to 1979. Most of the Baptist institutions that we serve and at which we studied were formed within this larger story.

Yet, the reality is that a number of those institutions no longer seek to relate to the Southern Baptist Convention in any way. Some of those institutions, like Baylor University, have recommitted themselves afresh to their “Baptist and Christian character.”62 Other institutions have sadly drifted in a direction that more mirrors the discontinuities reflected at Brown, Colby, Colgate, and others in previous generations. And still others have attempted to maintain their church-related identity, adopting a two-sphere approach to higher education that primarily emphasizes the Christian atmosphere or context of the institution.

6. Hopeful Trajectories. As we move toward the third decade of the twenty-first century, all six of the Southern Baptist seminaries have made renewed commitments to Southern Baptist life, to their identity as Southern Baptist institutions, to the full truthfulness of Holy Scripture, and to the transformational power of the gospel.63 Nearly two dozen Baptist colleges and universities remain intentional about their distinctive missional commitments as well as their Baptist identity. Part of our responsibility seems to involve attempting to help the next generation develop a framework for interpreting and relating to Southern Baptist life in a constructive and hopeful manner in the days ahead.

The proposal in the latter part of this article attempts to connect this vision for Baptist higher education with continuities found in the first eighteen centuries of the Christian tradition described in the first section of this article, while clearly recognizing the diversity within that tradition. The proposal is grounded in the inspired prophetic-apostolic witness of Holy Scripture, in the best of the Christian intellectual tradition, in a Christian worldview that affirms the importance of a commitment to the unity of knowledge, in an understanding that all knowledge, truth, and wisdom find their source in God, and in the importance of church connectedness.

In the midst of the confused cultural ethos of our day, we need commitments that are firm but loving, clear but gracious, encouraging the people of God to be ready to respond to the numerous issues and challenges that will come our way, without getting drawn into every intramural squabble in the church or in the culture.64 Let us pray that we will relate to one another in love and humility, bringing new life to our shared efforts in Christian higher education. We pray not only for renewed confessional convictions but also for a genuine orthopraxy that can be seen before a watching world, a world particularly in the Western Hemisphere that seemingly stands on the verge of giving up on the Christian faith.65 We trust that our collaborative efforts to advance distinctive Baptist higher education in the days to come will bring forth fruit, will strengthen partnerships, alliances, and networks, and that our shared work will be used of God to extend his kingdom.

Let us ask God to renew our shared commitments to academic excellence in our teaching, our learning, our research, our scholarship, and our service, as well as our whole life discipleship and churchmanship. We gladly join hands together with those within the larger Baptist story who desire to walk with us on this journey, seeking the good of all concerned as we serve together for the glory of our great God and the advancement of Baptist higher education in service to church and society.66

- See David S. Dockery, “Ministry and Seminary in a New Century,” Southern Seminary Magazine 62:2 (1994): 20–22; Dockery, “A Theology for the Church,” Midwestern Journal of Theology 1:1 (2003): 10–20. ↩︎

- For more detailed histories of this period, see: George M. Marsden, The Soul of the American University: From Protestant Establishment to Established Nonbelief (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994); Michael Reeves, Theologians You Should Know. An Introduction:

From the Apostolic Period to the 21st Century (Wheaton: Crossway, 2016); Gregg R. Allison, Historical Theology: An Introduction to Christian Doctrine (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2011); John Rogerson, Christopher Rowland, and Barnabas Lindars, The History of Christian Theology (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1988); Justo L. Gonzalez, The History of Theological Education (Nashville: Abingdon, 2015); Thomas A. Howard, Protestant Theology and the Making of the Modern German University (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006); and Glenn T. Miller, Piety and Intellect: The Aims and Purpose of Ante-Bellum Theological Education (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1990). ↩︎ - See David S. Dockery and Timothy George, The Great Tradition of Christian Thinking (Wheaton: Crossway, 2012). ↩︎

- See Virginia Stem Owen, “Fiction and the Bible,” Reformed Journal 38 (July 1988): 12–13; Richard N. Longenecker, Biblical Exegesis in the Apostolic Period (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1975); Karlfried Froehlich, Biblical Interpretation: Past and Present (Downers Grove: IVP, 1996). ↩︎

- See J. N. D. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines (San Francisco: Harper and Row, 1978); Robert M. Grant, Greek Apologists of the Second Century (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1988). ↩︎

- See R. V. Sellers, Two Ancient Christologies: A Study in the Christological Thought of the Schools of Alexandria and Antioch in the Early History of Christian Doctrine (London: SPCK, 1954). ↩︎

- See Craig A. Blaising, Athanasius (Lanham, MD: University Press, 1992). ↩︎

- See James K. A. Smith, On the Road with Saint Augustine (Grand Rapids: Brazos, 2019);

Matthew Levering, The Theology of Augustine of Hippo: A Biography (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013); and Beryl Smalley, The Study of the Bible in the Early Middle Ages, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Blackwell, 1952). ↩︎ - Gonzalez, History of Theological Education, 19–23. ↩︎

- See William C. Placher, A History of Christian Theology (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1983), 146. ↩︎

- See Jonathan Hill, The History of Christian Thought (Downers Grove: IVP, 2003), 131–60. ↩︎

- Mark A. Noll, “Reconsidering Christendom,” in The Future of Christian Learning (ed. Thomas A. Howard; Grand Rapids: Brazos, 2008), 23–70; Alister McGrath, The Intellectual Origins of

the European Reformation (Oxford: Blackwell, 2004), 11–117. ↩︎ - See John J. Piderit, “The University at the Heart of the Church,” First Things 94 (June/July

1999): 22–25; David Steinmetz, “The Superiority of Pre-critical Exegesis,” Theology Today 27 (1980): 31–32; E. Gilson, The Christian Philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas, trans. L. K. Shook (London: Victor Gollancz, 1957). ↩︎ - See David S. Dockery, “The History of Pre-critical Interpretation,” Faith and Mission 10 (1992): 3–33; and Dockery, “Foundations for Reformation Hermeneutics: A Fresh Look at Erasmus,” in Evangelical Hermeneutics (ed. M. Bauman and D. Hall; Camp Hill, PA: Christian Publications, 1995), 53–76. ↩︎

- See David S. Dockery, “Martin Luther’s Christological Principle: Implications for Biblical Authority and Biblical Interpretation,” in The Reformation and the Irrepressible Word of God, ed. Scott M. Manetsch (Downers Grove: IVP, 2019), 40–62. ↩︎

- See Timothy George, Theology of the Reformers (Nashville: B&H, 2013), 171–265. ↩︎

- See Gregory B. Graybill, The Honeycomb Scroll: Philip Melanchthon and the Dawn of the

Reformation (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2015), 145–337; Gonzalez, History of Theological Education, 70–77; Howard, Protestant Theology and the Making of the Modern University, 60–79. Also see Julie Reuben, The Making of the Modern University: Intellectual Transformation and the Marginalization of Morality (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1996). ↩︎ - See David S. Dockery, “Denominationalism: Historical Developments, Contemporary Challenges, and Global Opportunities,” in Why We Belong: Evangelical Unity and Denominational Diversity (ed. Anthony L. Chute, Christopher W. Morgan, and Robert A. Peterson; Wheaton: Crossway, 2013), 177–209. ↩︎

- H. Leon McBeth, The Baptist Heritage (Nashville: Broadman, 1987), 235. ↩︎

- See Donald D. Schmeltekopf and Dianna M. Vitanza, “Baptist Identity and Christian Higher

Education,” in The Future of Baptist Higher Education (ed. Donald D. Schmeltekopf and Dianna M. Vitanza; Waco: Baylor University Press, 2006), 3–21. ↩︎ - See Colin Brown, Christianity and Western Thought: A History of Philosophers, Ideas, and Movements (Downers Grove: IVP, 1990), 173–340; G. R. Evans, History of Heresy (London: Blackwell, 2003). ↩︎

- John H. Roberts and James Turner, The Sacred and Secular University (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000), 90. Even David Damrosch raised serious concerns about the impact of disciplinary specialization in his important work called We Scholars: Changing the Culture of

the University (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995). ↩︎ - The entire volume by Roberts and Turner addresses these developments over the decades. Also

see Reuben, The Making of the Modern University. ↩︎ - See the insightful discussion by Donald D. Schmeltekopf in “A Christian University in the

Baptist Tradition: History of a Vision” in The Baptist and Christian Character of Baylor (ed. Donald. D. Schmeltekopf and Dianna M. Vitanza with Bradley J. B. Toben; Waco: Baylor University Press, 2003), 1–20. ↩︎ - See the discussion by John F. Wilson in his “Introduction” to The Sacred and the Secular University, 3–16. ↩︎

- See James T. Burtchaell, The Dying of the Light: The Disengagement of Colleges and Universities from Their Christian Churches (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998). ↩︎

- See Walter B. Shurden, “The Southern Baptist Synthesis,” Baptist History and Heritage 16 (April 1981): 2–10. ↩︎

- See Timothy George and David S. Dockery, Baptist Theologians (Nashville: B&H, 1990); Bill J. Leonard, Baptists in America (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005); as well as James Leo Garrett Jr., Baptist Theology: A Four-Century Study (Macon, GA: Mercer, 2009), 713–26. ↩︎

- Leon McBeth was most likely correct when he observed that Baptists have often used confessions not only to proclaim Baptist distinctives but also to show how Baptists were similar to other orthodox Christians. See The Baptist Heritage, 66–69. ↩︎

- See Timothy George and David S. Dockery, Theologians of the Baptist Tradition (Nashville: B&H, 2001), 1–10; also, Keith Harper, ed., Through a Glass Darkly: Contested Notions of Baptist Identity (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2012). ↩︎

- McBeth, Baptist Heritage, 496. ↩︎

- See David S. Dockery, Southern Baptist Consensus and Renewal (Nashville: B&H, 2008),

134-67, 180-220. Material from this section has been adapted from the Norton Lectures given on the campus of Southern Seminary in March of 2018 and the Hester Lectures given at the annual meeting of the International Association of Baptist Colleges and Universities in June of 2018. ↩︎ - R. Orin Cornett, “Education Commission,” in Encyclopedia of Southern Baptists, vol. 1, ed. Clifton J. Allen and Norman Wade Cox (Nashville: Broadman, 1958), 392–94. ↩︎

- See the collection of diverse perspectives included in the compendium edited by Arthur L. Walker Jr., Integrating Faith and Academic Discipline (Nashville: SBC Education Commission, 1992). ↩︎

- See H. E. W. Turner, The Pattern of Christian Truth: A Study in the Relations between Orthodoxy and Heresy in the Early Church (1954; Reprint, Eugene, OR: Wipf And Stock, 2004); also see Timothy George, “The Pattern of Christian Truth,” First Things 154 (June/July 2005): 21–25. ↩︎

- William E. Hull, “Southern Baptist Higher Education: Retrospect and Prospect,” Unpublished Hester Lecture given at the annual meeting of the Association of Southern Baptist Colleges and Schools, 1996. ↩︎

- Provost Hull responded to earlier aspects of this vision by suggesting that the Baptist educational vision being proposed by people like David Dockery and Robert Sloan was too heavily influenced by northern evangelicals. See Hull, “Where are the Baptists in the Higher Education Dialogue?” in Gladly Learn and Gladly Teach (ed. John M. Dunaway; Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2005). ↩︎

- See David S. Dockery, Renewing Minds (Nashville: B&H, 2008), 1–46. ↩︎

- See David S. Dockery, “Toward a Theology of Higher Education,” Journal of the Evangelical

Theological Society 62:1 (2019): 5–22. ↩︎ - See Denise Lardner Carmody, Organizing a Christian Mind: A Theology of Higher Education

(Valley Forge: Trinity Press International, 1996), 1–65; Nathan Finn, “Knowing and Loving God: Toward a Theology of Christian Higher Education,” in Christian Higher Education: Faith, Teaching, and Learning in the Evangelical Tradition (ed. David S. Dockery and Christopher Morgan; Wheaton: Crossway, 2018), 39–58. Also, Bradley J. Gundlach, “Foundations of Christian Higher Education: Learning from Church History,” in Christian Higher Education, 121–38. ↩︎ - Stanley Hauerwas, The State of the University: Academic Knowledges and the Knowledge of God (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2007), 33–34. ↩︎

- See the fifteen-volume series Reclaiming the Christian Intellectual Tradition (ed. David S. Dockery; Wheaton: Crossway, 2012-2019); Matthew Y. Emerson, Christopher W. Morgan, and R. Lucas Stamps, eds., Baptists and the Christian Tradition: Toward an Evangelical Baptist Catholicity (Nashville: B&H, 2020). ↩︎

- See Donald E. Bloesch, Jesus Christ: Savior and Lord (Downers Grove: IVP, 1997). ↩︎

- See J. I. Packer and Thomas C. Oden, One Faith: The Evangelical Consensus (Downers Grove:

IVP, 1995); Albert Mohler, The Apostles’ Creed (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2019); and Timothy George, ed., Evangelicals and the Nicene Faith (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2011). Two recent volumes addressing this important subject will serve as helpful guides for those seeking to prioritize these commitments at their institutions. Please see Gavin Ortlund, Finding the Right Hills to Die On: The Case for Theological Triage (Wheaton: Crossway, 2020), and Rhyne Putman, When Doctrine Divides the People of God: An Evangelical Approach to Theological Diversity (Wheaton: Crossway, 2020). ↩︎ - See Charles Taylor, A Secular Age (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University

Press, 2007); James K. A. Smith, How (Not) to Be Secular: Reading Charles Taylor (Grand

Rapids: Eerdmans, 2014). ↩︎ - See Duane Litfin, Conceiving the Christian College (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2004); and

Mark A. Noll, Jesus Christ and the Life of the Mind (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2011). ↩︎ - See Dockery and Morgan, Christian Higher Education; David S. Dockery, ed., Faith and

Learning: A Handbook for Christian Higher Education (Nashville: B&H, 2012); and David S. Dockery, The Thoughtful Christian (Christ on Campus, ed. D. A. Carson and Scott Manetsch; Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, forthcoming). ↩︎ - See Malcolm B. Yarnell III, God the Trinity (Nashville: B&H, 2016). ↩︎

- See David S. Dockery, ed., Theology, Church, and Ministry: A Handbook for Theological Education (Nashville: B&H, 2017). ↩︎

- See David S. Dockery, “Blending Baptist with Orthodox in the Christian University,” in The Future of Baptist Higher Education, 83–100; also, Dockery, Renewing Minds, 78–90; 141–64. ↩︎

- See C. Stephen Evans, “The Christian University and the Connectedness of Knowledge,” in The Baptist and Christian Character of Baylor, 21–40. ↩︎

- See Anthony J. Diekema, Academic Freedom and Christian Scholarship (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2000). ↩︎

- See Evans, “The Christian University and the Connectedness of Knowledge.” ↩︎

- Dockery, Renewing Minds, 1–22. ↩︎

- See David S. Dockery, “Fruit of the Spirit,” in Dictionary of Paul and His Letters, ed. Gerald F.

Hawthorne, Ralph P. Martin, and Daniel E. Reid (Downers Grove: IVP, 1993), 316–19. ↩︎ - See Mark Noll, Jesus Christ and the Life of the Mind. ↩︎

- See Dockery, Renewing Minds, 35–51. ↩︎

- See Philip W. Eaton, Engaging the Culture, Changing the World: The Christian University in a

Post-Christian World (Downers Grove: IVP, 2011). ↩︎ - See Peter Cha, “The Importance of Intercultural and International Approaches in Christian

Higher Education,” in Christian Higher Education, 505–24; Bruce Riley Ashford, “Mission, the Global Church, and Christian Higher Education,” in Christian Higher Education, 525–43. ↩︎ - See Kevin J. Vanhoozer and Daniel J. Treier, Theology and the Mirror of Scripture: A Mere Evangelical Account (Downers Grove: IVP, 2015). ↩︎

- See Anthony Chute, Nathan Finn, and Michael A. G. Haykin, The Baptist Story: From English Sect to Global Movement (Nashville: B&H, 2015); Thomas S. Kidd and Barry Hankins, Baptists in America: A History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015); Bill J. Leonard, Baptist Ways: A History (Valley Forge, PA: Judson, 2003). ↩︎

- See Schmeltekopf and Vitanza, The Baptist and Christian Character of Baylor. Robert Sloan deserves much credit for this reality and for his overall framing of the “Baylor 2012” vision. ↩︎

- See David S. Dockery, ed., Southern Baptist Identity: An Evangelical Denomination Faces the Future (Wheaton: Crossway, 2009); Jason K. Allen, ed., The SBC and the 21st Century: Reflection, Renewal, and Recommitment (Nashville: B&H, revised 2019). ↩︎

- See Dockery, Southern Baptist Consensus and Renewal, 206–18. ↩︎

- See Timothy George and John Woodbridge, The Mark of Jesus: Loving in a Way the World

Can See (Chicago: Moody, 2005); Francis A. Schaeffer, The Church at the End of the Twentieth Century: Including the Church Before the Watching World (Wheaton: Crossway, 1985). ↩︎ - Some of the material in this article has been adapted from David S. Dockery and Christopher Morgan, eds., Christian Higher Education: Faith, Teaching, and Learning in the Evangelical Tradition (Wheaton: Crossway, 2018); David S. Dockery, ed., Theology, Church and Ministry: A Handbook for Theological Education (Nashville: B&H, 2017); David S. Dockery and Timothy George, The Great Tradition of Christian Thinking: A Student’s Guide (Wheaton: Crossway, 2012); David S. Dockery, Renewing Minds: Serving Church and Society through Christian Higher Education (Nashville: B&H, 2008); and David S. Dockery, Southern Baptist Consensus and Renewal (Nashville: B&H, 2008). I am genuinely grateful to Keith Harper and to the University of Tennessee Press for permission to adapt portions of this article from a chapter on Southern Baptist education in the forthcoming volume, edited by Keith Harper, Southern Baptists Observed and Revisited (Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, forthcoming). ↩︎