Sacred music both shapes and reflects beliefs. Significantly, both lyrics and musical style contribute to this process. As Scott Aniol notes, “Aesthetic form shapes propositional content . . . doctrinal facts take the shape of the aesthetic form in which they are carried.”1 While discussing contemporary hymn arrangements, Joshua Busman argues that changes in musical style, form, and climax can color or even alter the meaning of a song, even when the text remains identical to the original.2 As Greg Scheer summarizes, “Repertoire Is Theology.”3 Unpacking this theology requires consideration of the text, music, and their interaction.4

This study examines expressions of the vertical and horizontal dimensions of the Christian life as expressed in recordings by American singer-songwriter Chris Tomlin. In particular, it considers those songs in which a change in point of view in the lyrics is paired with a significant formal, melodic, or textural event in the music, resulting in a heightened awareness of the worshipper’s relation to God and to other people, especially fellow believers. While Tomlin is far from the only worship artist to include lyrics with such grammatical shifts, he nevertheless provides a valuable case study because of his dominance in Contemporary Worship Music (CWM). His accolades include numerous Dove Awards from the Gospel Music Association and a Grammy for Best Contemporary Christian Album (And if Our God Is for Us . . .).5 Tens of thousands of college students have been introduced to his music through Passion Conferences, with which Tomlin has been involved since its founding in 1997.6 Perhaps most important, however, is the fact that Tomlin’s songs are widely sung in church services, as evidenced by their regular appearance in the Top 25 and Top 100 lists maintained by Christian Copyright Licensing International (CCLI).7

The relationship between CWM and the perceived value of worshiping in the context of a Christian congregation is complex. In unpacking connections, the three sections of this article move from general context towards specific case studies focused on Tomlin’s music. Part I considers the significance of point of view in CWM in light of past congregational music and ethnographies of current musical practice. Part II analyzes a corpus of one hundred three songs drawn from ten of Tomlin’s albums, highlighting patterns in lyrics and musical structure typical of his writing and arranging. Part III identifies three types of interactions between lyrical shifts and musical form, closely analyzing representatives of each type drawn from the larger corpus. Interestingly, over half of Tomlin’s songs in this study include an internal change in speaker or audience. Shifts in point of view coupled with musical expression can heighten awareness of both the vertical relation between a worshiper and God and also the horizontal relation among Christians.

Part I: Pronouns, Congregational Music, and “Really Worshiping”

Christian worship invokes a network of relationships. The act of worship by definition involves the vertical relationship between a worshiper and God. However, worship—including worship through song—also places a person in a horizontal relation to other believers. Indeed, both the vertical and the horizontal appear in Jesus’s summary of the law: “Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart and with all thy soul and with all thy mind. This is the first and great commandment. And the second is like it, Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself.”8 In practice, both dimensions impact relationships both within and outside the church. Monique M. Ingalls demonstrates the role CWM plays in shaping four interrelated types of evangelical congregations: churches, conferences, concerts, and audiovisual materials.9 Consideration of the relative emphases of the vertical and horizontal dimensions surface in discourse about the lyrics of worship music in general and of CWM in particular. For instance, in a podcast hosted by Chris Tomlin, Christian singer-songwriter Christy Nockels describes the rise of CWM as “the church . . .shift[ing] from singing songs about God to singing songs to God.”10 This idea can be traced back at least as far as John and Carol Wimber of the charismatic Vineyard Movement.11 While demonstrably false in the narrow sense, this bold claim underscores the importance of point of view, word choice, and value of congregation to studies of CWM.

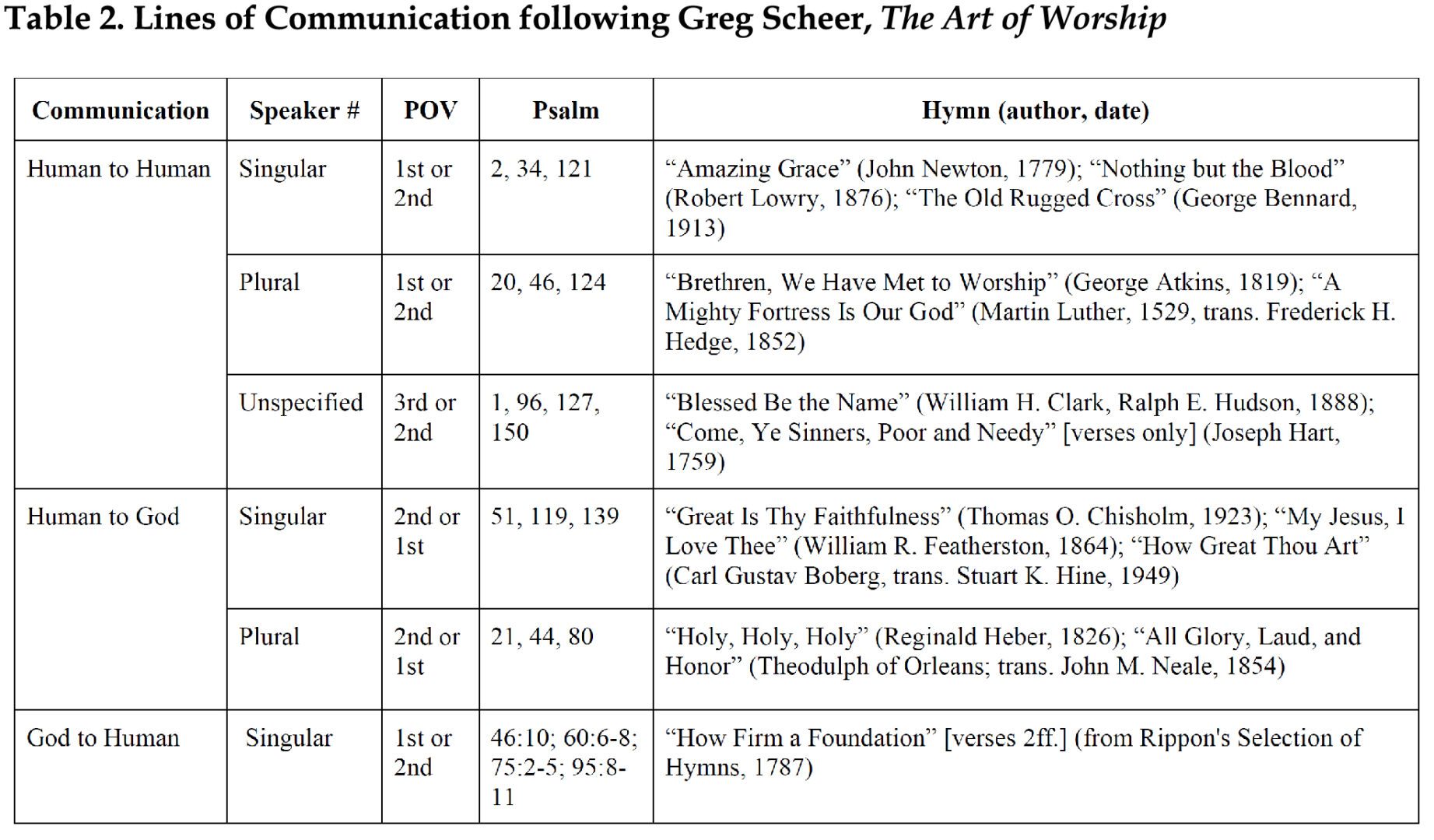

The “lines of communication” Scheer identifies in Christian lyrics provide a useful starting place for considering point of view in both traditional and modern worship music. He emphasizes three of these as primary: human to human, human to God, and God to human.12 A human speaker is usually presumed to be a Christian, though the real or imagined human hearers may be fellow believers, non-Christians, or a mixture of the two. While in a theological sense all quotations from the Bible can be interpreted as communications from God, lyrics that specify God as the speaker in a dramatic sense appear only sparingly. This might be due in part to the tension such lyrics create between the understood speaker and the reality of a human singer. Each line has the potential to interact with more than one of the grammatical points of view listed in table 1. In particular, each category can be expressed in first person, second person, or a fluid mixture of the two. Lyrics in first person tend to emphasize the experience and attributes of the speaker(s), while lyrics in second person emphasize the same for the recipient(s). Third person, when used, most often surfaces in lyrics in the human to human line that focus on ideas rather than the nature of the speaker.

Christian lyrics have used a variety of points of view for centuries. This is evident even when confining attention to English- speaking churches. The Old Testament book of Psalms—the only texts even permitted to be sung in many Protestant churches in the early days of the American colonies—includes both statements to God and to people.13 Likewise, hymnals explore multiple points of view.

Table 1. Grammatical Points of View

| Singular | Plural | |

| 1st | I am | We are |

| 2nd | You are | You (all) are |

| 3rd | It is/He is/She is | They are |

Table 2 illustrates this variety, providing representatives for each of Scheer’s lines.14 The examples of both the human to human and the human to God categories are subdivided based on whether the lyrics specify a single speaker, indicate a group, or sidestep the question through avoidance of personal pronouns. The third column indicates possibilities for point of view, listing the most likely option first. Confession and testimony tend toward first person, while praise and supplication gravitate toward second person. The third line, God to human, is the least common, often only appearing in part of a song’s lyrics. Examples of the first two lines abound in these older repertoires. While congregational music with lyrics addressed directly to God originated long before the advent of the pop-rock style of modern praise bands, CWM tends to emphasize second person singular.15 Third person, perhaps the option most closely associated with “singing about God,” is less common in this repertoire.

CWM departs from the formal tone of many older settings of psalms and hymns in favor of the current vernacular. Specifically, CWM embraces modern pronouns (You/Your) over the antiquated pronouns of many older hymns (Ye/Thou/Thee/Thy/Thine).16 In comparison to the shift from singing in Latin to singing in German that took place under Martin Luther in the early days of the Reformation, this change might seem unremarkable.17 However, some at- tach deeper theological significance to the issue, claiming that the older language stresses God’s transcendence while modern everyday language emphasizes God’s immanence.18 Marva J. Dawn advocates striving for balance, noting the dangers of elevating one attribute over the other: “Worship that focuses on God’s transcendence with- out God’s immanence becomes austere and inaccessible; worship that stresses God’s immanence without God’s transcendence leads to irreverent coziness.”19

Hymns and CWM also differ in means and amount of internal repetition. On one hand, congregational hymns tend to be strophic while most CWM uses more complex structures involving verses, choruses, and contrasting bridges. On the other, CWM tends to use a smaller harmonic vocabulary than hymns, often employing only four or five chords from the same diatonic set. The most pronounced difference, though, involves the repetitions of words. Ruth attributes this to a change in tone: “CWS [contemporary worship songs] come before divinity in worship in terms of bold address to God, eagerly, and repeatedly, whereas EH [evangelical hymns] tend to praise in indirect ways.”20 As Scheer notes, “hymns typically develop one idea, whereas Praise & Worship songs repeat an idea . . . verbatim or with slight variations.”21 In fact, CWM often repeats individual words or phrases enough to merit the nickname “7–11 songs” (i.e., seven words sung eleven times).22

Additionally, CWM lyrics are often colloquial and even intimate, a fact not lost on critics pejoratively referring to this genre as “Jesus-is-my-boyfriend (or girlfriend) music.”23 Such “overt emphasis on the love relationship between God and the worshipper” reflects the influence of Vineyard’s writings and music.24 Evidence of the ubiquity of this trait includes the unabashed title Lovin’ on Jesus, a book by Swee Hong Lim and Lester Ruth on the history of contemporary worship.25 Jenell Williams Paris identifies twenty-seven of the seventy-seven songs that occupied CCLI’s Top 25 song lists from 1989 to 2005 as “romantic,” and Keith Drury explores both positive and negative reactions to this trend.26 More generally, Scott Aniol notes increased emphasis on “themes such as human freedom, personal experience, and decision to change one’s self more than on theocentric worship.”27

Cautions against self-centeredness surface even in charitable commentaries on CWM. Chris Tomlin writes:

Our increasingly me-centered culture has even influenced a lot of our worship songs. There’s so much “me,” “mine,” “I,” and “Lord, do this for me.” I’m not saying it’s wrong or theologically incorrect to word a song like this. (If that were so, we would have to throw many of the Psalms out as well. David cries out to God about himself all through his songs.) It’s just that we must be careful not to keep all the attention on us. But our flesh, our sinful selves, can confuse us. Confuse us into thinking that the world revolves around us, that somehow our desires should be at the center of our response to God.28

Such lyrics encourage some worshipers to downplay the importance or even the presence of the congregation in the midst of a corporate worship service. In his study of a church in Canada, Gordon Adnams discusses the irony in comments by one worshiper in particular:

Eyes are closed to shut out all of the other singers who are necessary for the occasion of singing in a worship service. But at some point in time, they apparently become a distraction for a really worshipping member whose goal appears to be a private, inner awareness of communicating to God the personalized feelings named in the communally sung words. . . . For one who is really worshipping, a song becomes “personal truth.”29

The emphasis on the need for an individual to worship God is not surprising in light of evangelical theology, which teaches the need for each individual “to be transformed through a ‘born-again’ experience and a lifelong process of following Jesus.”30 What is more surprising is the ambivalent attitude towards fellow-worshipers during the act of worshiping through music, even in the midst of a live worship service.31

The differences in lyrics between traditional psalm settings and hymns on one hand and most CWM on the other are multifaceted. While psalms and older hymns employ a wide range of points of view, CWM favors second person singular. Containing a higher degree of repetition than older styles, CWM lyrics emphasize simple wording and intimate imagery. Sometimes in the act of “singing to God” with CWM, the emphasis on the experience of individuals can eclipse the value of fellow worshipers. As Drury notes, “the church could use more lyrics expressing the love relationship between Jesus and the collective church, replacing ‘I, my, and mine’ with ‘we, our, and ours.’”32 In light of these trends, CWM songs that employ shifts in speaker, audience, and point of view might heighten rather than suppress awareness of the corporate dimension of congregational singing.

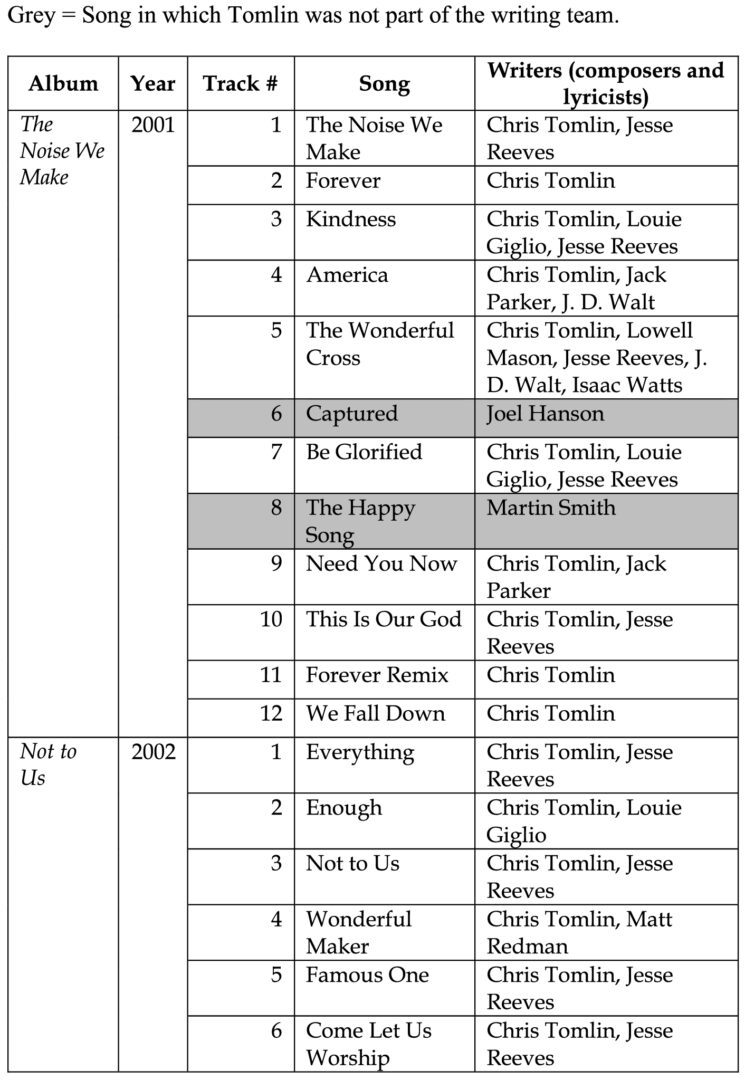

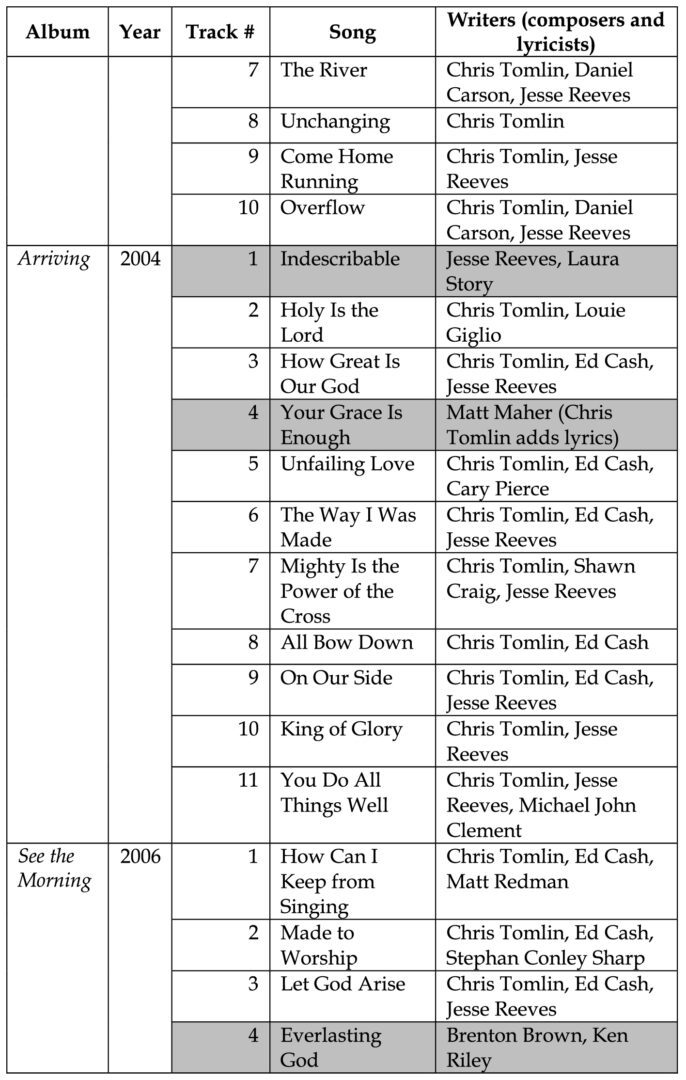

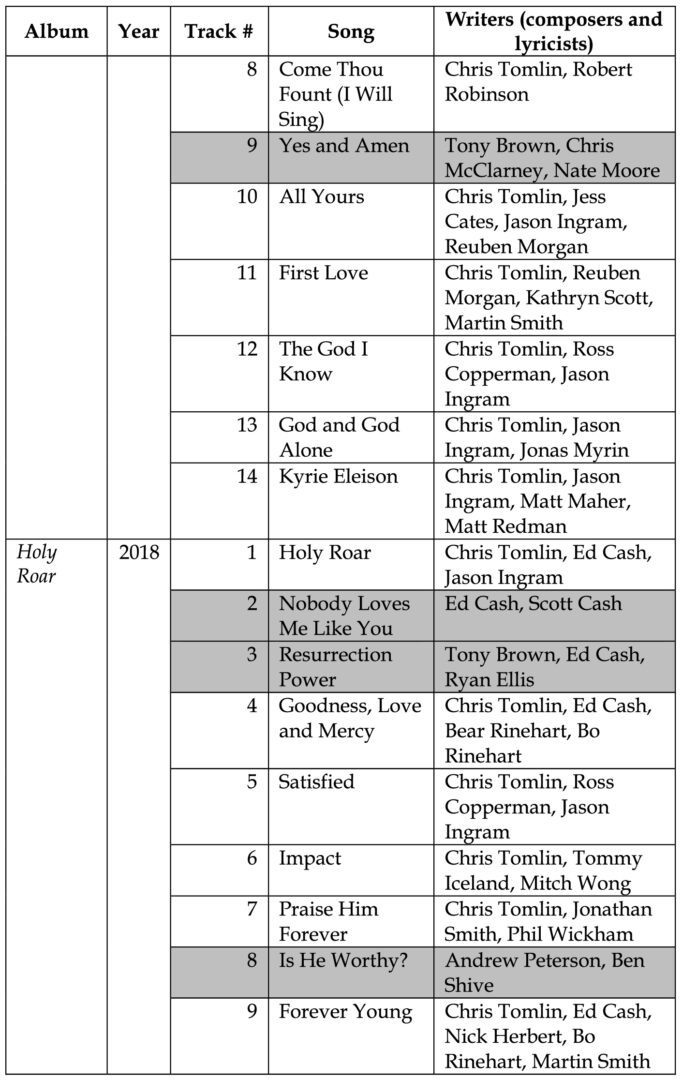

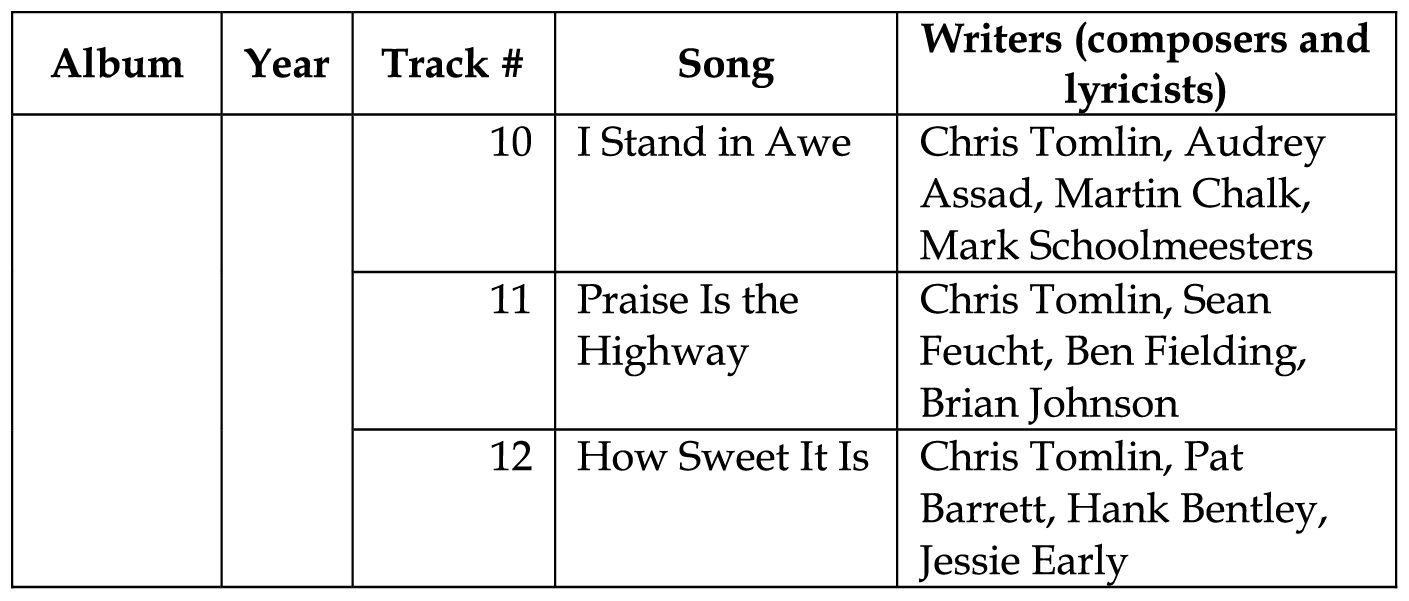

Part II: Characteristics of Tomlin’s Studio Albums

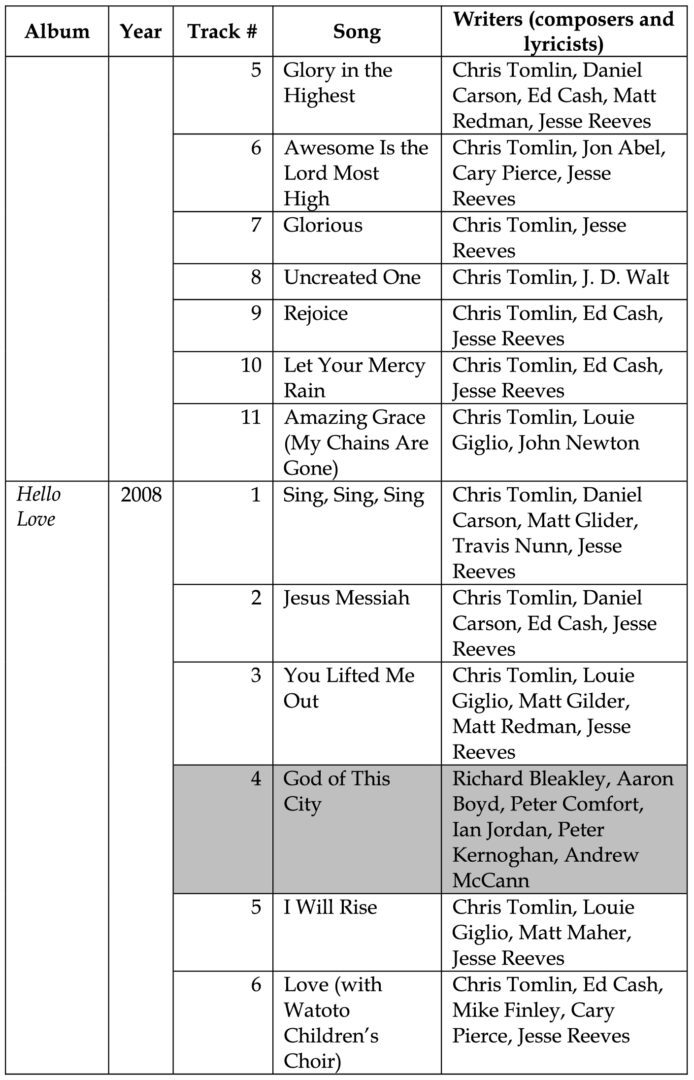

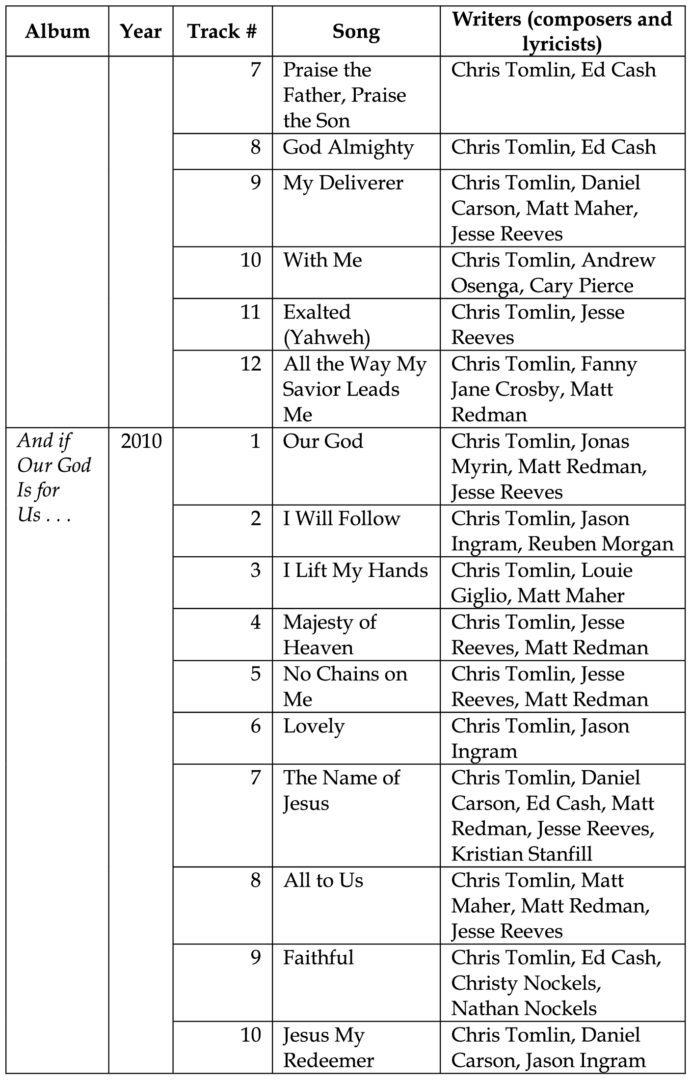

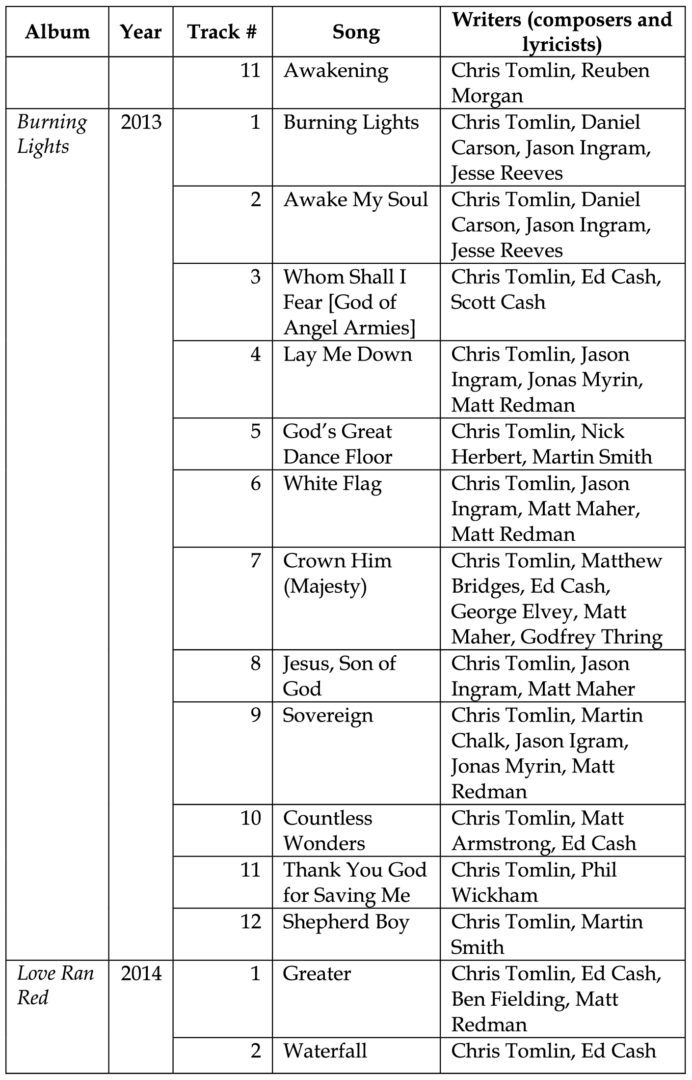

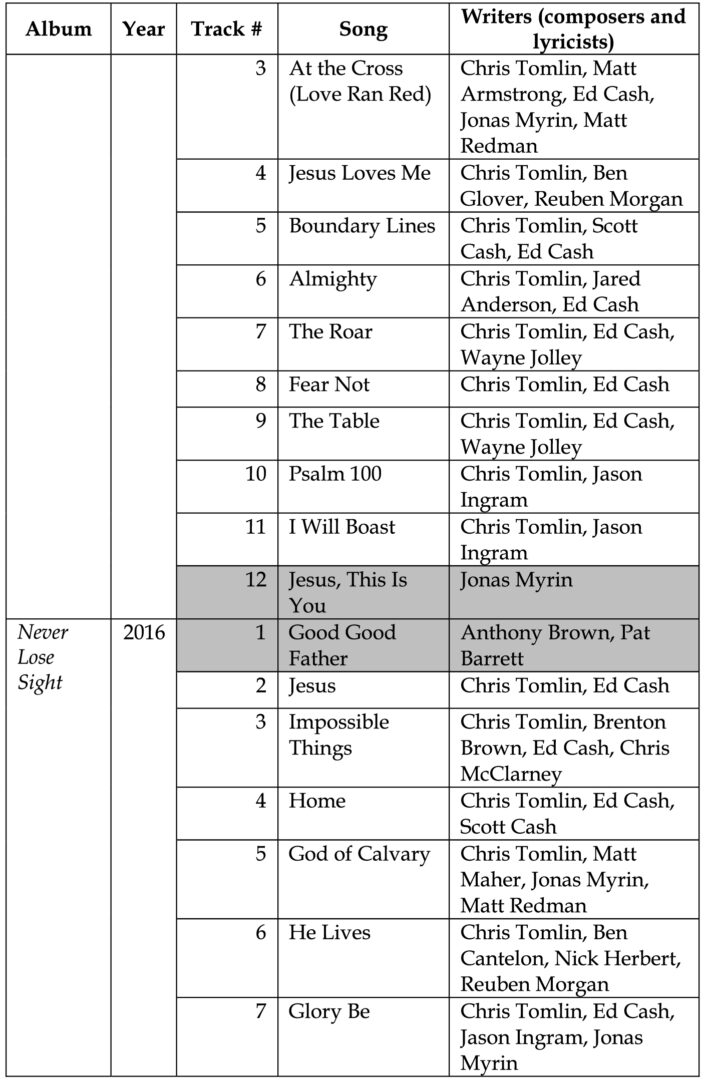

The ten albums listed in figure 1 provide the main source material for this study.33 These include Tomlin’s solo studio albums released from 2001 to 2018 that are not compilations and are not associated with a specific event or a season (such as Christmas). The analysis that follows focuses on these particular recordings, consulting published transcriptions and other recordings as secondary sources.34 As with much CWM, most of the songs Tomlin has recorded involved co-authorship of the lyrics, music, or both. The Appendix lists the contents of all ten albums, specifying authorship for each of the one hundred seventeen tracks. The remainder of this study excludes only thirteen of these: the twelve in which Tomlin is not credited as a songwriter (indicated in grey), and the titular track of Burning Lights, which essentially functions as an introduction to the album. While both the long and shortened versions of “Forever” are mentioned below, the general statistics count only the long version. Despite the influence of a variety of pastors, producers, and performers, the remaining one hundred three songs constitute a cohesive corpus. Surveying patterns in the music and lyrics of Tomlin’s output provides necessary context for close analysis of individual songs.

The Noise We Make (2001)

Not to Us (2002)

Arriving (2004)

See the Morning (2006)

Hello Love (2008)

And if Our God Is for Us . . . (2010)

Burning Lights (2013)

Love Ran Red (2014)

Never Lose Sight, deluxe ed. (2016)

Holy Roar (2018)

Each issues as a compact disc by sixsteprecords/Sparrow Records

Figure 1. Chris Tomlin Discography

The vast majority of Tomlin’s songs follow some variation of verse-chorus-bridge form.35 The basic pattern includes an instrumental introduction (I), two iterations of a verse-chorus pair (V, C), a contrasting bridge (B), a return to the chorus (C), and a concluding tag (T) or instrumental passage (I). In some of Tomlin’s songs, a sung introduction (N) replaces the instrumental introduction or the introduction is minimized or omitted. Possible additions to the basic scheme include one or more reiterations of the chorus, internal instrumental breaks, a prechorus (P), or an additional verse. Patterns emerge when grouping songs by the number of verses containing distinct words. Table 3 shows the form of the eleven songs with only a single distinctive verse, which usually appears twice as part of a verse-chorus pair. Table 4 shows two distinct verses in sixty-five songs, nearly two-thirds of the corpus. The only change from the first category is here each distinct verse typically appears only once in a verse-chorus pair. Songs with three different verses take a slightly different approach, as shown in the twenty-six songs in table 5. Here, the first and second verses are usually grouped together before the first chorus, which is followed by the third verse and its attendant chorus. These songs thus move from an emphasis on the verses at the beginning of the song to an emphasis on the chorus by the end. The single remaining song in the corpus, “Amazing Grace (My Chains Are Gone)” is anomalous in comparison to Tomlin’s other songs (including his other hymn arrangements) for including four distinct verses, the last of which concludes the song (I V1 V2 C V3 C C V4 T).

Table 3. Form of Tomlin’s Songs with One Verse

| Song (11 with 1 verse = 11%) | Form |

| Be Glorified | V I V C I V C I B C T |

| Boundary Lines | T V I C I V I T C T T/C I |

| Exalted (Yahweh) | V C1 V C1 C1 I B C2 C2 I B |

| Goodness, Love and Mercy | V C V C I B C I |

| Holy Is the Lord | I V P C V P C B P C I T |

| Kyrie Eleison | I V C C B C I |

| Let Your Mercy Rain | I V C1 V C1 C2 B C1 C2 C2 I |

| Need You Now | I V C V C B I C C I |

| Sovereign | I V C V C B C T I |

| The Noise We Make | I V C I V C B C I B I |

| We Fall Down | I V C V C C C T |

Table 4. Form of Tomlin’s Songs with Two Verses

| Song (65 with 2 verses = 63%) | Form |

| All the Way My Savior Leads Me | V1 C V2 C C T |

| All Yours | I V1 C V2 C B C C T |

| Almighty | I V1 C1 V2 C B C T I |

| America | I B V1 C I V2 C I B C T |

| At the Cross (Love Ran Red) | I V1 C V2 C B C T |

| Awake My Soul | I V1 C I V2 C I C C T |

| Awakening | I V1 C V2 C C I B I B I T |

| Awesome Is the Lord Most High | I V1 C V2 C B C C C T |

| Come Let Us Worship | I V1 C1 V2 C1 I C2 I |

| Countless Wonders | V1 C V2 C B C C C T |

| Crown Him (Majesty) | I V1 C V2 C B C C T |

| Enough | C I V1 C I V2 C B C T |

| Everything | I V1 C1 V2 C1 C2 B T |

| Famous One | I C I V1 C I V2 C C I C |

| Fear Not | C1 V1 C1 V2 C1 C2 I B C1 C2 |

| Song (65 with 2 verses = 63%) | Form |

| Glorious | I V1 C V2 C C B C C C I |

| Glory Be | I V1 V2 C I V2 C B I C I |

| Glory in the Highest | I V1 C1 V2 C1 B C2 C2 C2 I |

| God Almighty | I V1 C I V2 C I B C I |

| God and God Alone | I V1 C V2 C B C C B T |

| God of Calvary | I V1 C1 I V2 C1 B C2 I |

| God’s Great Dance Floor | I V1 P I V2 P C1 I P C1 I C2 I C2 C2 I |

| Greater | I V1 C V2 C B C C T I |

| He Lives | I V1 C V2 C B C C |

| Holy Roar | V1 C V2 C B C C T |

| How Can I Keep from Singing | I V1 C V2 C B C T |

| How Great Is Our God | I V1 C V2 C B C C C |

| I Lift My Hands | I V1 C I V2 C C B C C T |

| I Stand in Awe | V1 C V2 C B C C T |

| I Will Follow | N V1 C V2 C B C C |

| I Will Rise | I V1 P C V2 P C B I C T |

| Impact | I V1 P C V2 C I B C B |

| Impossible Things | I V1 C I V2 C B1 C C B2 I V1 T |

| Jesus Loves Me | I V1 C V2 C B C T |

| Jesus Messiah | I V1 C V2 C B C T |

| Kindness | I V1 V1 C I V2 C C I V1 |

| King of Glory | I V1 C V2 C B T |

| Lay Me Down | I V1 C I V2 C I B C T I |

| Let God Arise | I V1 C I V2 C I B C T |

| Lovely | I V1 C1 V2 C1 B C2 C1 T |

| Made to Worship | I V1 C V2 C B C C T I |

| Mighty Is the Power of the Cross | I V1 C V2 C B C C T |

| My Deliverer | I V1 P C V2 P C C B C T I |

| No Chains on Me | I V1 C I V2 C I B C T |

| Not to Us | I V1 C V2 C B T |

| On Our Side | I V1 C V2 C I C C T |

| Song (65 with 2 verses = 63%) | Form |

| Our God | I V1 V2 C I V2 C C I B C C B |

| Overflow | V1 C V2 C I B T |

| Praise Him Forever | I V1 C I V2 C B C T |

| Psalm 100 | I V1 C I V2 C B I C I |

| Rejoice | I V1 C I V2 C C B C C I |

| Satisfied | C V1 C V2 C B1 B2 C B1 |

| Shepherd Boy | I V1 C1 V2 C1 I C2 C2 T |

| Sing, Sing, Sing | I C V1 V2 C V1 C I C C I |

| Thank You God for Saving Me | I V1 C V2 C I B1 B2 C |

| The God I Know | I V1 C V2 C I B C B C F |

| The River | V1 C1 V2 C1 C2 B T |

| The Roar | V1 C1 V2 C1 B C1 C2 |

| The Way I Was Made | I V1 C V2 C B C T |

| Unfailing Love | I V1 C V2 C B C C T |

| Waterfall | I V1 C I V2 C I B C T |

| White Flag | I V1 C V2 C I B C C B I |

| With Me | I V1 P C V2 P C I V1 C T |

| You Do All Things Well | I V1 C V2 C B C C I |

| You Lifted Me Out | I V1 C I V2 C I B C I |

Table 5. Form of Tomlin’s Songs with Three Verses

| Song (26 with 3 verses = 25%) | Form |

| All Bow Down | I V1 V2 C V3 C B C C I |

| All to Us | I V1 V1 C I V2 C C B I V3 T |

| Come Home Running | I V1 V2 C V3 C C T |

| Come Thou Fount (I Will Sing) | I V1 V2 C I V3 C C V3b |

| Faithful | I V1 V2 C V3 C B C |

| First Love | I V1 V2 P C V3 P C C I |

| Forever | I V1 P V2 P C1 I V3 P C1 C1 B P C2 C2 C2 C2 |

| Forever Young | I V1 V2 C V3 C C T |

| Song (26 with 3 verses = 25%) | Form |

| Home | I V1 V2 C I V3 C B C T |

| How Sweet It Is | V1 C V2 C B V3 C C |

| I Will Boast | I V1 V2 C I V3 C C T I |

| Jesus | V1 V2 C1 V3 C1 B C2 C2 T |

| Jesus My Redeemer | I V1 V2 C I V3 C I B I C I T |

| Jesus, Son of God | I V1 V2 C V3 V3 C B C |

| Love (with Watoto Children’s Choir) | N V1 V2 C V3 B I C T |

| Majesty of Heaven | I V1 V2 C V3 C I B C T |

| Praise Is the Highway | I V1 V2 C V3 C B I C I T |

| Praise the Father, Praise the Son | I V1 V2 C V3 C C B C |

| The Name of Jesus | V1 V2 P C V3 P C I B P C T |

| The Table | V1 V1 C V2 V3 C B C T |

| The Wonderful Cross | I V1 V2 C V3 C C I V3 I C C |

| This Is Our God | I V1 V2 C1 V3 C1 C2 T |

| Unchanging | I V1 V2 C V3 C I B C C C I |

| Uncreated One | I V1 C I V2 C I V3 C I |

| Whom Shall I Fear [God of Angel Armies] | I V1 V2 C V3 C B C C T |

| Wonderful Maker | I V1 V2 P C V3 P C B C I |

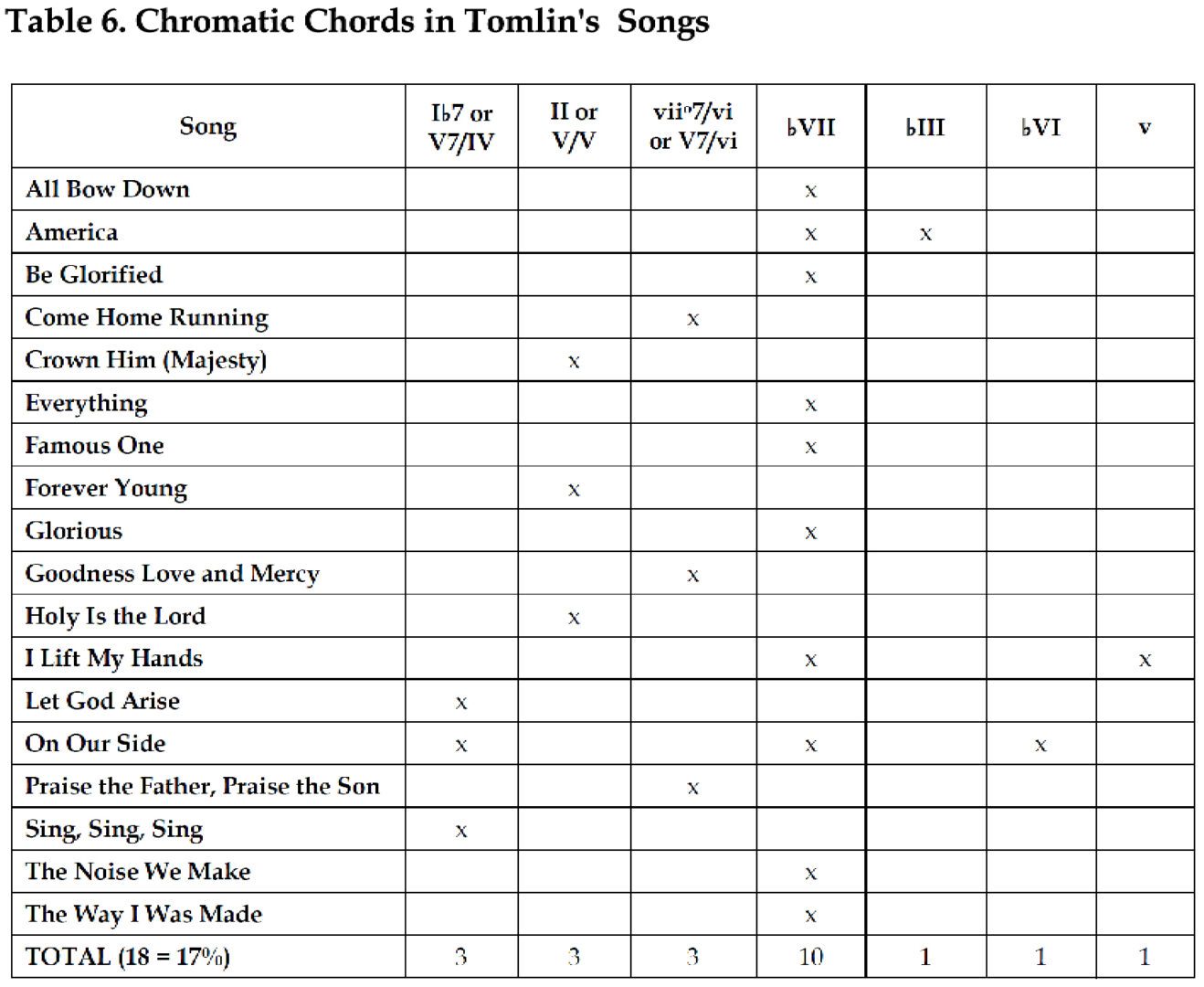

Like much of CWM, the harmony, texture, and melodic con- tour of Tomlin’s repertoire adheres to the norms of secular poprock.36 The vast majority include only triads, sevenths, and sus chords diatonic in major. Only eighteen songs (about 17%) contain applied chords or mixture harmonies. These are listed in table 6, which shows ♭VII to be the chromatic chord appearing most frequently. Loops of two to four chords are common.

Examples include the openings of “Let Your Mercy Rain” (IV–I) and “Unchanging” (I–V–IV over a tonic pedal). Verses often avoid tonal closure, instead generating tension for the arrival of a tonic chord at the start of the chorus. Such is the case in “Holy Roar.” Verses tend to feature a relatively low vocal register and thin texture, while choruses tend to reach into a higher vocal register supported with thicker texture. For example, “Whom Shall I Fear [God of Angel Armies]” rises in vocal tessitura and dynamic level with section changes. The melody of the verse spans the pitches C3–C4, mainly accompanied by guitars. In contrast, the chorus and bridge rise to A3–F4, noticeably increasing dynamics with synthesizer and more prominent percussion.

Tomlin’s lyrics often combine quotation, paraphrase, and original description on the given theme. Some songs focus on a single passage from the Bible: “Goodness, Love and Mercy” paraphrases Psalm 23, and “We Fall Down” draws from Revelation 4.37 Others touch on elements drawn from more than one passage of Scripture. “Holy Is the Lord” combines Isaiah 6:3 with Nehemiah 8:6.38 Others incorporate phrases from sacred music of previous eras. For instance, “Kyrie Eleison” incorporates the opening words of the traditional mass ordinary, and “Glory Be” sets the lesser doxology. Several songs simply intersperse a new chorus into verses of a traditional hymn: examples include “Amazing Grace (My Chains Are Gone),” “Come Thou Fount (I Will Sing),” “Crown Him (Majesty),” and “The Wonderful Cross.” Other songs include more subtle references to hymns. “Thank You God for Saving Me” includes phrases from two familiar hymns: “my hope is built on nothing less” comes from the opening of “The Solid Rock,” and “great is Your faithfulness” changes only one word from the opening of “Great Is Thy Faithfulness.” Such connections to older traditions are deliberate.39 Tomlin writes: “Young people these days don’t want a faith that’s just the latest thing. They’re excited to know that we stand in a long line of worshipers—a huge cloud of witnesses—who have gone before.”40 Thus, changes in the use of pronouns or lines of communication are not due to the source materials themselves, which remain centered on the Bible and traditional texts.

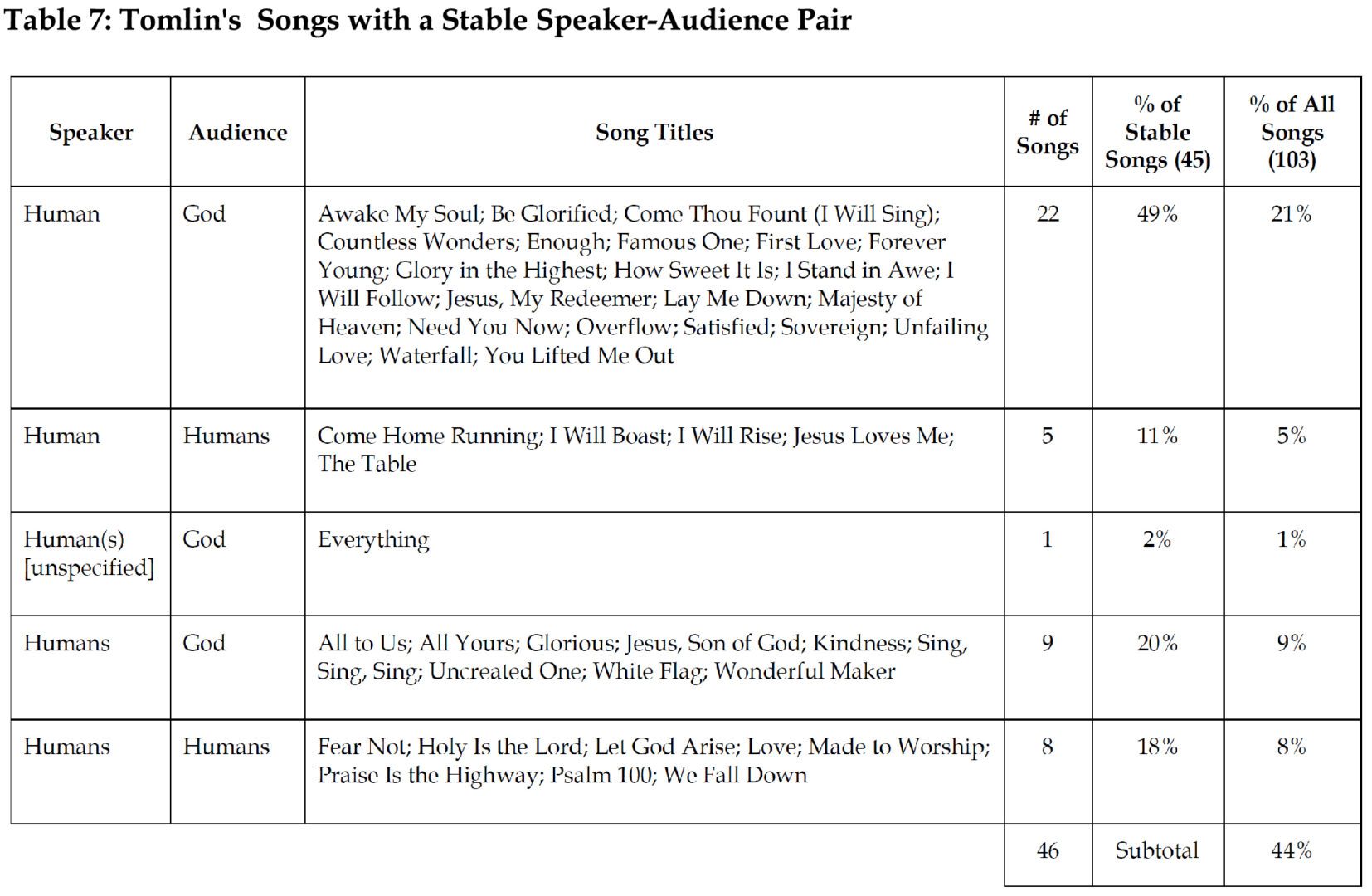

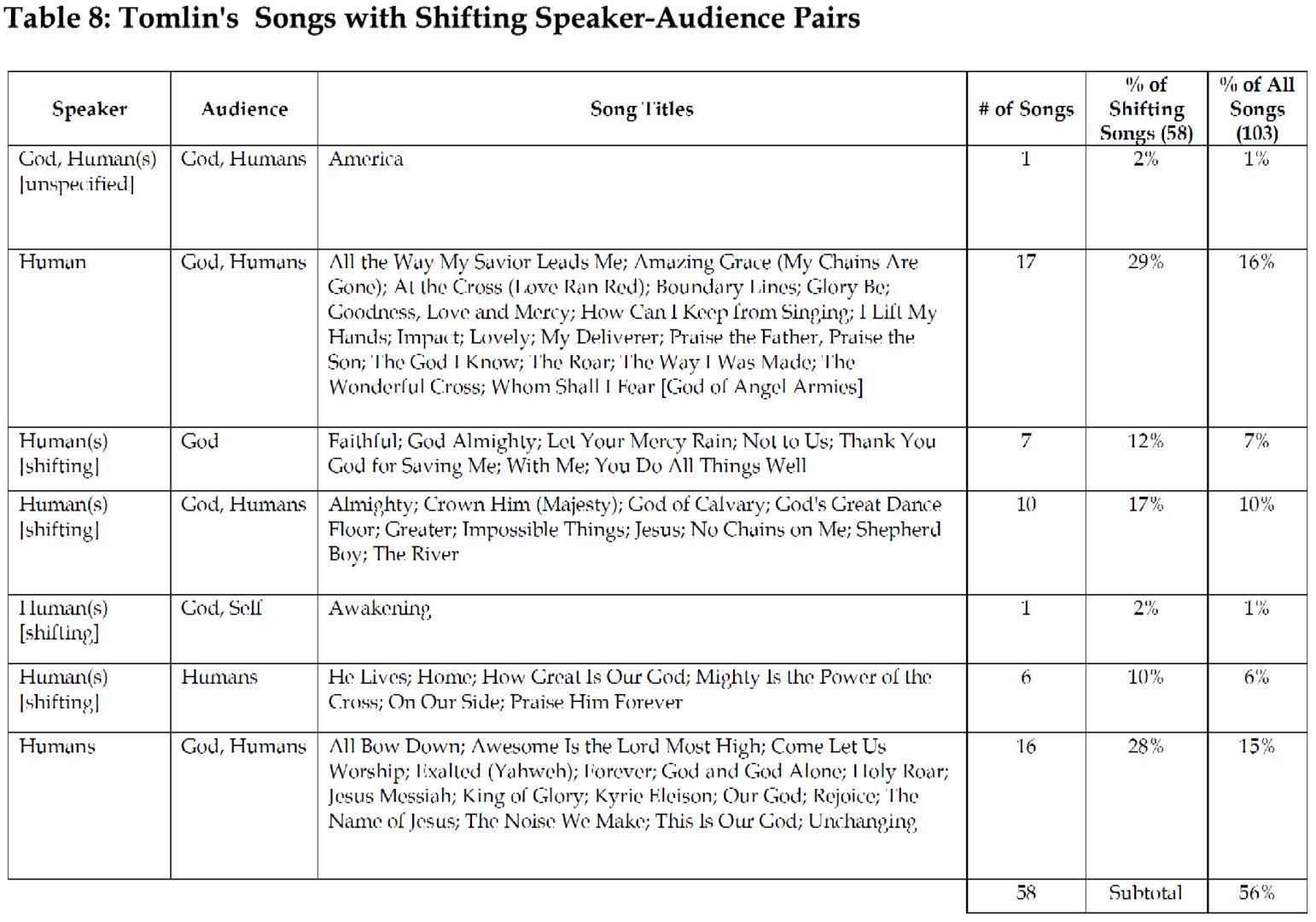

Nevertheless, Tomlin’s songs do explore multiple possible pairings of speaker and audience. While in some sense God is always the “audience” of songs sung in worship, here the term refers to the recipient implied by a close reading of the text, which most often is either God or other humans. Table 7 provides an overview of songs with a stable pairing of a speaker with an audience. Specifically, these are songs in which pronouns referring to the speaker are either all singular or all plural, and the entirety of the song is addressed either to God or to other humans. As the subtotal shows, such songs constitute slightly less than half of the corpus. Most interestingly, songs in which an individual person sings exclusively to God with no acknowledgement of other people comprise only about one-fifth of the corpus, a lower proportion than stereotypes of CWM might suggest. Table 8 shows the remaining songs, namely those that contain changes in speaker, audience, or both. The two largest groups include one human dividing attention between God and other humans, and several humans likewise dividing attention between God and humans. Together, these two groups comprise about one third of the corpus. Four of the other groups feature shifts between singular and plural pronouns in reference to the speaker, sometimes voicing the words of an individual and sometimes voicing the words of a congregation. The subtype in which the speaker number changes but the audience remains God alone is remarkable in that it acknowledges both the horizontal connection of an individual to fellow believers while still focusing on the vertical connection to God.

This survey of one hundred three of Tomlin’s songs summarizes general patterns in the music and lyrics. The vast majority are in verse-chorus-bridge form, mostly varying only the number of verses and instrumental breaks present. Harmony mostly entails only diatonic chords. Vocal range and density of instrumentation contribute far more to the creation of energy and tension in these songs. Lyrics tend to be infused with quotations, paraphrases, and concepts from the Bible, sometimes also referencing lyrics and even tunes from older sacred music. The corpus employs various lines of communication, exploring more than one pairing of speaker and audience in over half of the songs. This summary provides a necessary backdrop for the close analyses below.

Part III: Analyses

Two main features inform analysis of a worship song that contains shifts in speaker, audience, point of view, or some combination thereof. The first involves the main dimension emphasized in the song, which may or may not change from start to finish. For instance, a song might open with lyrics addressed to God and end with lyrics addressed to people, thus moving from vertical worship to horizontal testimony or exhortation. The reverse is also possible, emphasizing the horizontal at the beginning and the vertical at the end. Alter- natively, the start and end might have a similar emphasis, bookending changes that occur only in the middle of the text. The second main feature, which helps to shape the first, is the location of each shift in the context of the song’s form. As the analyses of Tomlin’s songs below demonstrate, these include three possible strategies. The first aligns each shift with a boundary between formal sections, thus using the song form to underscore major changes in the lyrics. The second entails shifting within a formal section, often exploring the interaction of the vertical and horizontal dimensions. The third involves altering the words to the chorus, often changing from a general statement of truth to a personal expression in the altered version. The subsequent analyses of Tomlin’s songs explore each strategy in turn, demonstrating the overall trajectories idiomatic to each.

Changes between Sections

Table 9 lists Tomlin’s twenty-seven songs that change speaker, audience, and/or point of view only at a major formal boundary. This strategy pairs common musical changes between sections (verse, chorus, bridge, etc.) with less common changes in the text’s perspective, fostering coherence of the latter. Placing changes between sections is the most flexible of the three main strategies, allowing for a wide variety of narratives exploring vertical and horizontal dimensions. The case studies below sample three possibilities.

Table 9: Tomlin’s Songs with Shifts between Sections

| Song (27/58 = 47%) | Speaker | Audience | POV |

| America | God, Human(s) [unspecified] | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd |

| All the Way My Savior Leads Me | Human | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd |

| Glory Be | Human | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd |

| Goodness, Love and Mercy | Human | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd |

| How Can I Keep from Singing | Human | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd |

| Impact | Human | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd |

| Lovely | Human | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd |

| My Deliverer | Human | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd |

| Praise the Father, Praise the Son | Human | God, Humans | 2nd |

| The God I Know | Human | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd |

| The Way I Was Made | Human | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd |

| Whom Shall I Fear [God of Angel Armies] | Human | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd |

| Faithful | Human(s) [shifting] | God | 2nd |

| God Almighty | Human(s) [shifting] | God | 2nd |

| Not to Us | Human(s) [shifting] | God | 2nd |

| Song (27/58 = 47%) | Speaker | Audience | POV |

| Thank You God for Saving Me | Human(s) [shifting] | God | 2nd |

| With Me | Human(s) [shifting] | God | 2nd |

| You Do All Things Well | Human(s) [shifting] | God | 2nd, 3rd |

| Almighty | Human(s) [shifting] | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd |

| The River | Human(s) [shifting] | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd |

| He Lives | Human(s) [shifting] | Humans | 1st, 3rd |

| God and God Alone | Humans | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd |

| Holy Roar | Humans | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd, 3rd |

| Jesus Messiah | Humans | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd, 3rd |

| King of Glory | Humans | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd, 3rd |

| The Noise We Make | Humans | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd |

| Unchanging | Humans | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd |

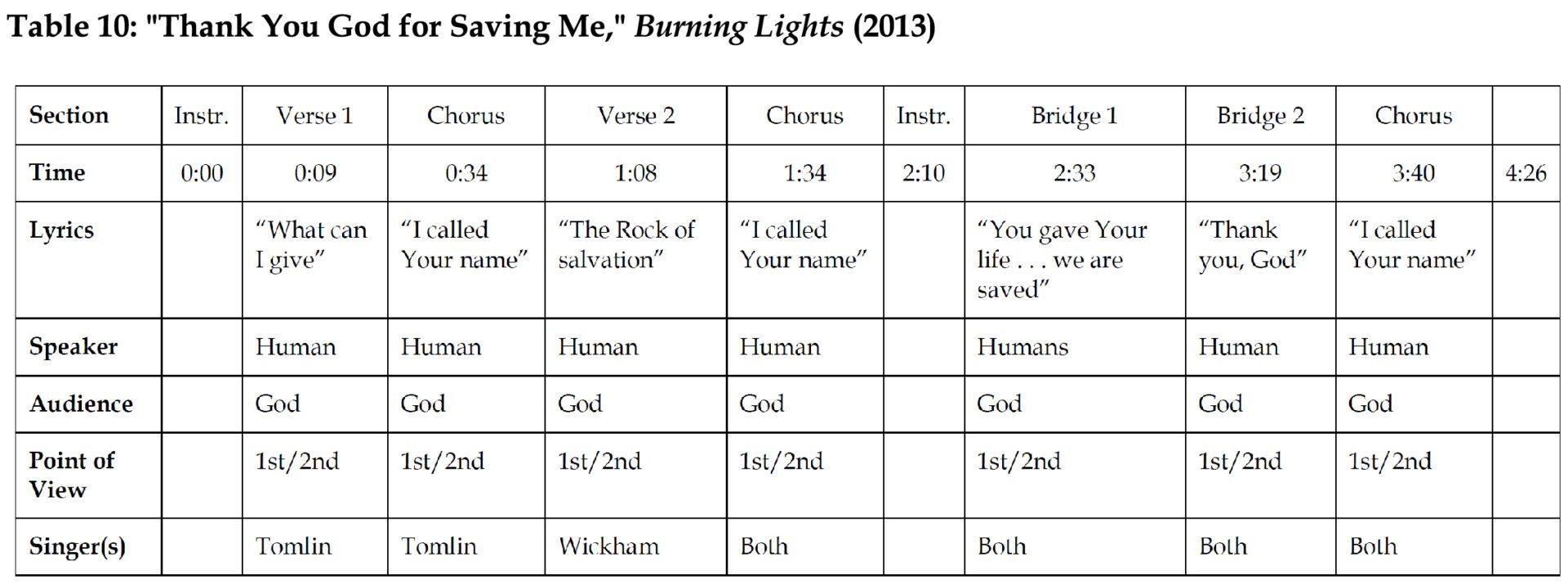

“Thank You God for Saving Me” from Burning Lights (2013) adds a horizonal dimension to the main vertical dimension through both a temporary shift from singular to plural pronouns and judicious use of two singers, Chris Tomlin and Phil Wickham. The text contains the flexible mixture of first and second person common in intimate lyrics. As the title implies and as table 10 summarizes, most of the song depicts a single believer thanking God for salvation. The single exception is the first bridge. Two elements of the text mark this passage as the song’s climax. First, the bridge contains the most detailed account of the basis of salvation, describing the substitutionary atonement made possible through Jesus’s death on the cross and victorious resurrection. Second, the switch to plural pronouns situates the individual believer in the community of believers, further accentuating the wonder of salvation. The bridge’s shift in speaker number was foreshadowed earlier in this duet between Tomlin and Wickham. As shown in figure 11, each verse features only a single singer. They do not sing simultaneously until the second iteration of the cho- rus, shortly before the first bridge. Both the chorus and first bridge feature homorhythm and mostly parallel motion between the singers. The lyrics of the second bridge switch back to singular pronouns, and the singers reflect this by replacing their rhythmic unison with call-and-response, stressing individual voices. While this song starts and ends with a single believer thanking God for the salvation received individually, the climactic bridge uses text and orchestration to highlight the grandeur of salvation and the resulting body of believers.

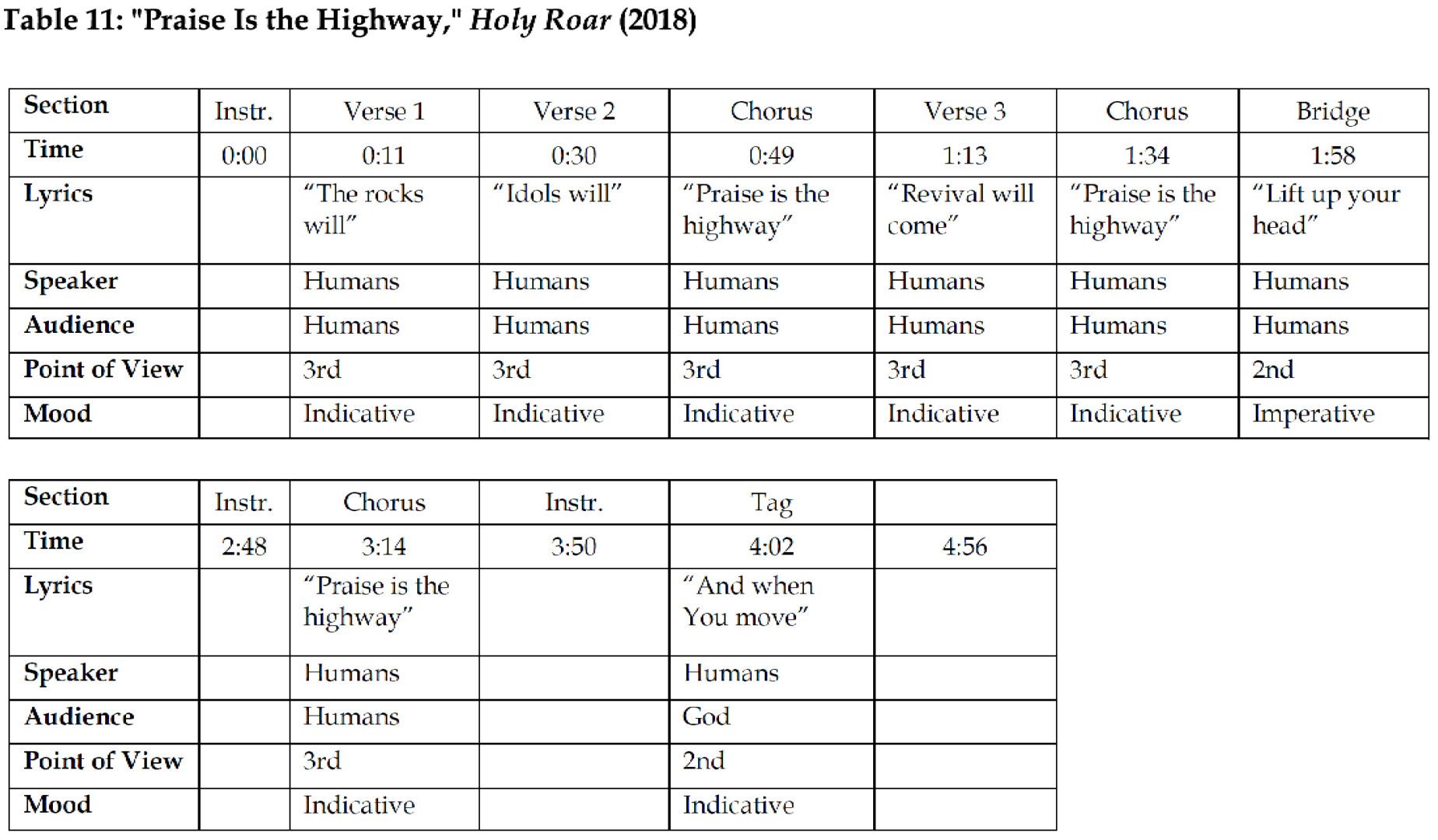

While the previous example changes only speaker number, “Praise Is the Highway” from Holy Roar (2018) maintains the speaker number while changing audience and point of view. As shown in table 11, most of this song features humans speaking to other humans. The chorus and verses emphasize third person and the indicative mood. These sections minimize personal pronouns, thus focusing the audience’s attention on external states and actions rather than internal experience. The bridge interrupts the act of observation with a series of commands in second person. The indicative leads to the imperative; God’s character and power and relationship to his people demand their response in praise. As with the previous example, the musical contrast of the bridge highlights the most important idea in the song. Unlike the previous example, this song contains a second contrasting passage. The tag departs from the main body of the song in two ways, one pertaining to the music and one pertaining to the text. Like many tags, the vocal declamation of this tag is improvisa- tory, less conducive to congregational singing. For the first time in the song, the lyrics directly address God. In effect, this tag fulfills the demands of bridge, responding to the call to praise in the bridge with praise itself in the tag. While most of this song depicts horizontal communication, the goal first commanded and then illustrated is to enact vertical communication.

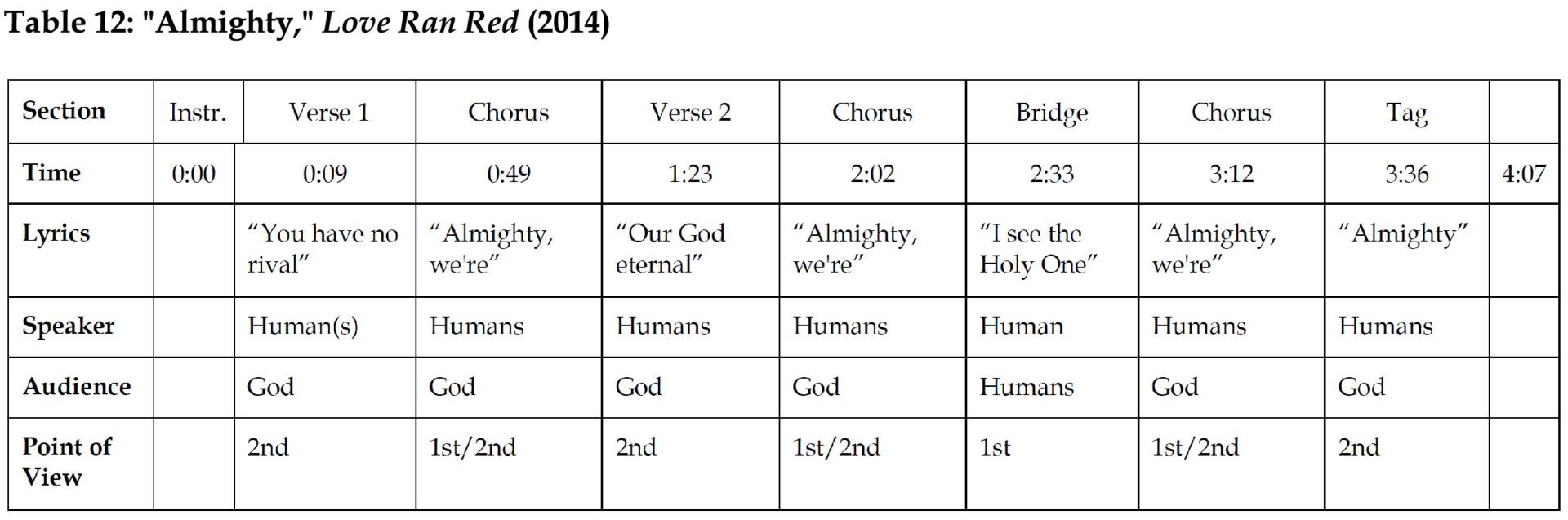

“Almighty” from Love Ran Red (2014) recombines factors yet again to differentiate the bridge from the rest of the song. As table 12, shows, most of the song addresses God. The first verse so firmly embraces second person that it avoids specifying whether the speaker is singular or plural. Plural pronouns enter in the chorus and second verse, clarifying that believers are singing to God together. In contrast, the bridge depicts an individual addressing the congregation, using singular pronouns in first person to shift to personal testimony. The opening of the bridge is marked through a drastic thinning of the orchestration. Tomlin sings alone, and, with the exception of acoustic piano, all instruments fall silent. In contrast, volume surges at the second pass through the bridge’s text. Here Tomlin sings in a higher part of his range, supported with a return of the instruments and the backup singers. This explosion of sound assists with the individual’s re-assimilation into the worshiping congregation, which is maintained through the subsequent chorus and tag. This song combines the horizonal elements of individual testimony and shared congregational experience with the vertical act of praising and worshiping God in language addressed directly to Him.

While all three of these examples align changes in the text with boundaries in the musical form, each provides a different mixture of vertical and horizontal emphases. While “Thank You God for Saving Me” addresses God throughout, the internal shift from singular pronouns to plural pronouns and back again situates the believer in relation to other Christians. “Praise Is the Highway” focuses primarily on declaration of truth to humans, rising to address God directly only near the end. “Almighty” starts and ends with multiple believers focused on God, breaking for the testimony of an individual in the middle.

Changes within a Section

Table 13 lists the twenty-one songs that change speaker, au- dience, or point of view within a section. This strategy trades stability for increased excitement, heightening awareness of both the horizontal and the vertical dimensions. Many small-scale shifts emerge as joyous exclamations, as two examples illustrate.

Table 13: Tomlin’s Songs with Shifts within Sections

| Song (21/58 = 36%) | Speaker | Audience | POV |

| Amazing Grace (My Chains Are Gone) | Human | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd, 3rd |

| At the Cross (Love Ran Red) | Human | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd, 3rd |

| Boundary Lines | Human | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd, 3rd |

| The Wonderful Cross | Human | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd |

| I Lift My Hands | Human | God, Humans (self?) | 2nd, 3rd |

| Let Your Mercy Rain | Human(s) [shifting] | God | 2nd |

| Crown Him (Majesty) | Human(s) [shifting] | God, Humans | 2nd, 3rd |

| God’s Great Dance Floor | Human(s) [shifting] | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd |

| Greater | Human(s) [shifting] | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd, 3rd |

| Impossible Things | Human(s) [shifting] | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd, 3rd |

| No Chains on Me | Human(s) [shifting] | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd, 3rd |

| Awakening | Human(s) [shifting] | God, Self | 2nd |

| Home | Human(s) [shifting] | Humans | 1st, 3rd |

| How Great Is Our God | Human(s) [shifting] | Humans | 1st, 2nd, 3rd |

| Song (21/58 = 36%) | Speaker | Audience | POV |

| Mighty Is the Power of the Cross | Human(s) [shifting] | Humans | 1st, 3rd |

| On Our Side | Human(s) [shifting] | Humans | 1st |

| Praise Him Forever | Human(s) [shifting] | Humans, Creation | 2nd |

| Kyrie Eleison | Humans | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd |

| Our God | Humans | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd |

| Rejoice | Humans | God, Humans | 2nd |

| The Name of Jesus | Humans | God, Humans | 2nd, 3rd |

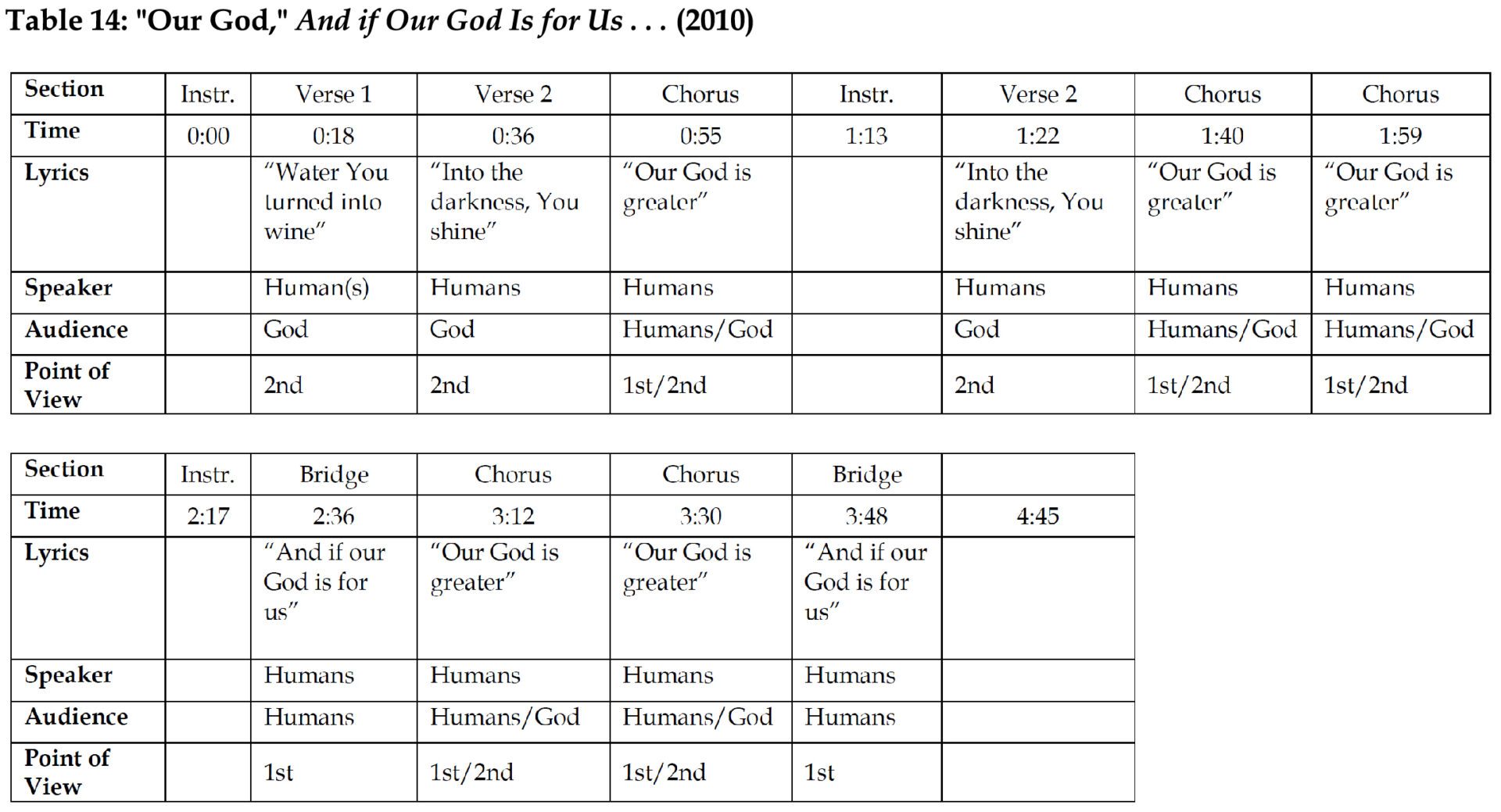

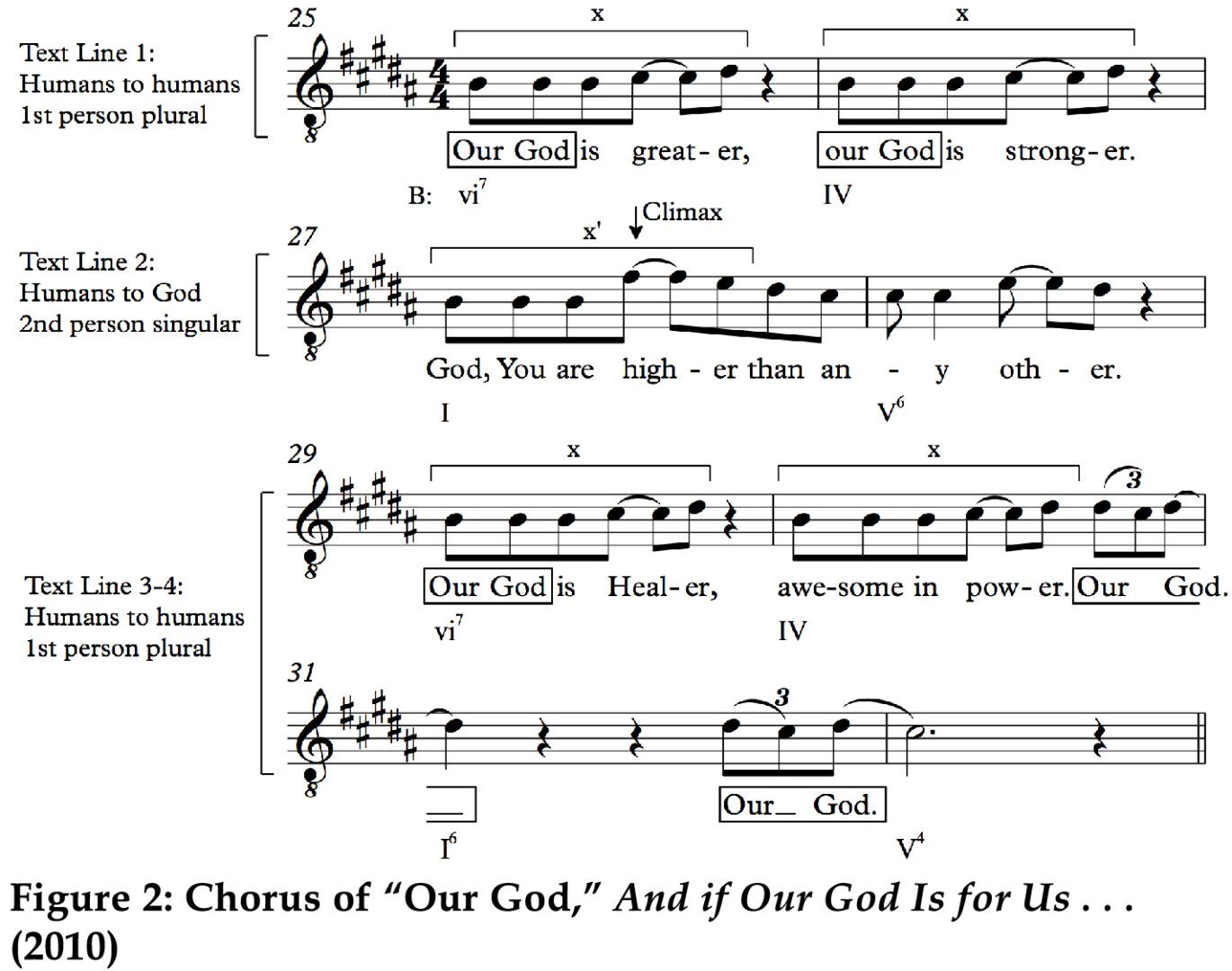

The chorus of “Our God” rapidly juxtaposes the vertical orientation of the verses with the horizontal orientation of the bridge. Table 14 provides an overview of the song, showing the shifts in audience. The verses praise God directly for his actions and attributes. The bridge—which appears both in its normal position and again at the song’s end—involves the congregation encouraging each through paraphrases of Apostle Paul’s rhetorical question from Ro- mans 8:31: “If God is for us, who can be against us?” Incidentally, the bridge’s opening line also serves as the album title: And if Our God Is for Us . . . (2010). The melody climbs higher as the text repeats, moving from emphasizing ^ 1 and ^2 at the beginning to sustaining ^5 at the end of the bridge. The heart of this song, though, resides in the cho- rus. Figure 2 highlights the repetition of a short motive as well as the five iterations of the titular phrase “Our God.” Most of this chorus is addressed to humans, who are understood to be fellow worshipers. The second line departs from the others in two ways: the audience changes from humans to God, and the point of view changes from first person to second person. The melody underscores this shift by altering motive x to climax on “higher,” touching on the ^5 featured at the end of the bridge. Excited explanation of God’s greatness to others erupts into praise addressed directly to God. The brevity of this extraordinary line is balanced by its frequent recurrence; table 14 notes the five full passes through the chorus. Changing the audience not only between but within sections in this song thus celebrates God, his work on His people’s behalf, and the joy of worshiping alongside fellow believers.

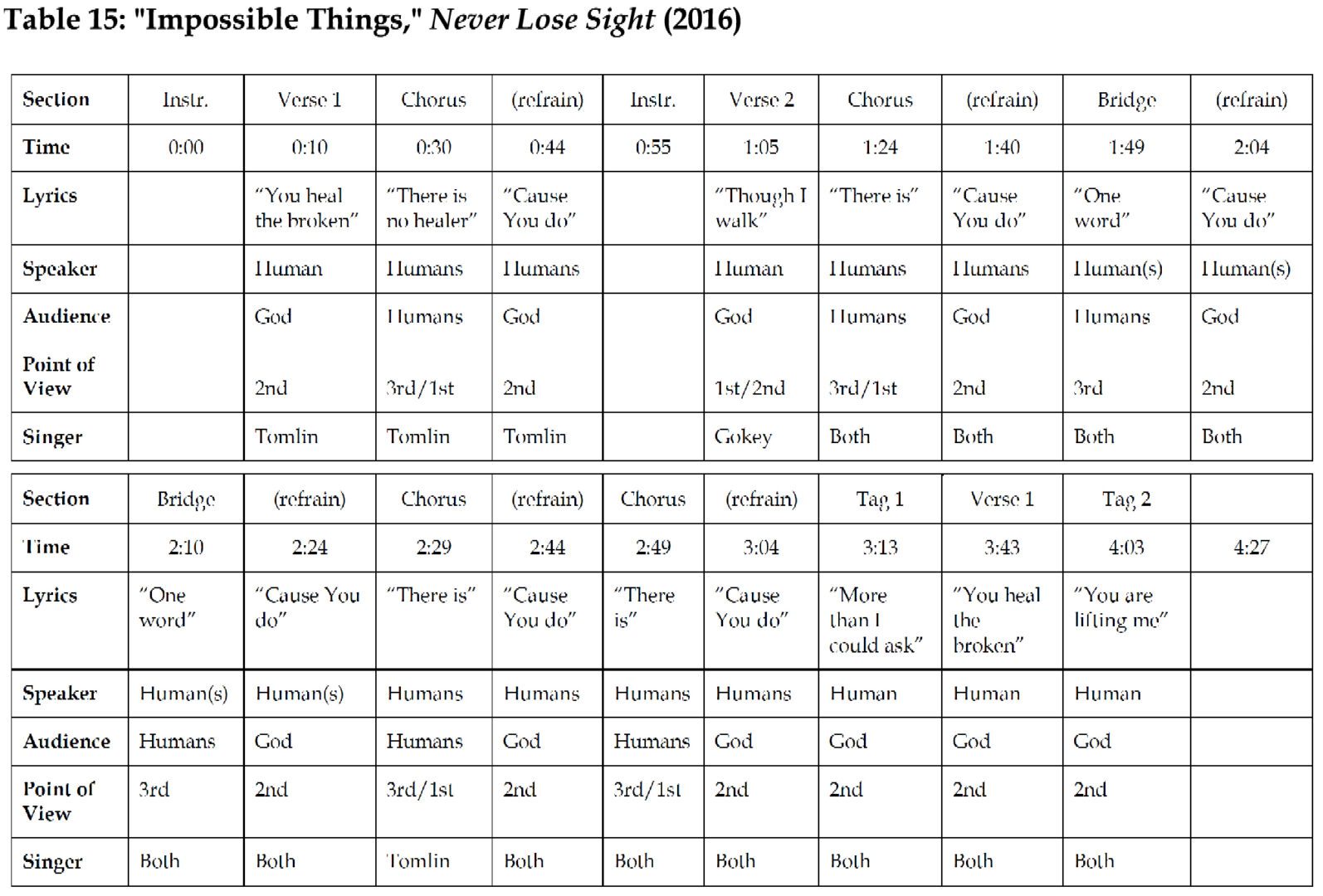

“Impossible Things” from Never Lose Sight (2016) engages all three types of changes between and within sections to situate a believer in relation to both God and to other Christians. Table 15 provides an overview of this complex example. The verse lyrics feature a single human singing to God. Appropriately, Tomlin sings the first verse, and Danny Gokey sings the second, emphasizing the singular pronouns by taking turns. Notably, the song concludes with a return to the first verse and a second tag based upon it, meaning that the song starts and ends with the same speaker, audience, and point of view. The beginning of the chorus provides sharp contrast, changing all three factors. Believers sing to each other of God’s matchlessness until reaching the final line that abruptly switches the address back to God himself with the line, “‘Cause You do impossible things.” Unusually, this passage acts as a refrain at the end of not only every chorus, but also both iterations of the bridge. Like the chorus, the first part of the bridge addresses humans.

The speaker number is not specified here, as the language remains consistently in third person, listing examples of “impossible things” that require only “One word” from God to transpire. This list moves from the external (“walls start falling”) to the physical (“blind will see”) to the spiritual (“sinner’s forgiven”). The last is the most won- drous in this list, motivating the shifts brought by the refrain. This mention of forgiveness serves as the keystone for the arch form of this song. All of the relationships this song explores—a single believer to God, members of the church to each other, and the body of believers to God—are made possible through God’s “impossible” forgiveness.

Changes in Chorus Repeats

While most songs use the same lyrics for each iteration of the chorus, the ten songs listed in table 16 break this convention. In each, the first version of the chorus gives way to a second version of the chorus somewhere in the second half of the song. While used less frequently than shifts between or within sections discussed above, unidirectional alterations to the chorus exaggerate the end-accented nature of most pop-rock songs.41 This strategy lends itself well to a powerful shift from speaking to other humans to speaking directly to God.

Table 16: Tomlin’s Songs with Changes in Chorus Repeat

| Song (10/58 = 17%) | Speaker | Audience | POV |

| The Roar | Human | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd |

| God of Calvary | Human(s) [shifting] | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd, 3rd |

| Jesus | Human(s) [shifting] | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd, 3rd |

| Shepherd Boy | Human(s) [shifting] | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd, 3rd |

| All Bow Down | Humans | God, Humans | 2nd, 3rd |

| Awesome Is the Lord Most High | Humans | God, Humans | 2nd |

| Come Let Us Worship | Humans | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd |

| Exalted (Yahweh) | Humans | God, Humans | 2nd, 3rd |

| Forever | Humans | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd, 3rd |

| This Is Our God | Humans | God, Humans | 1st, 2nd |

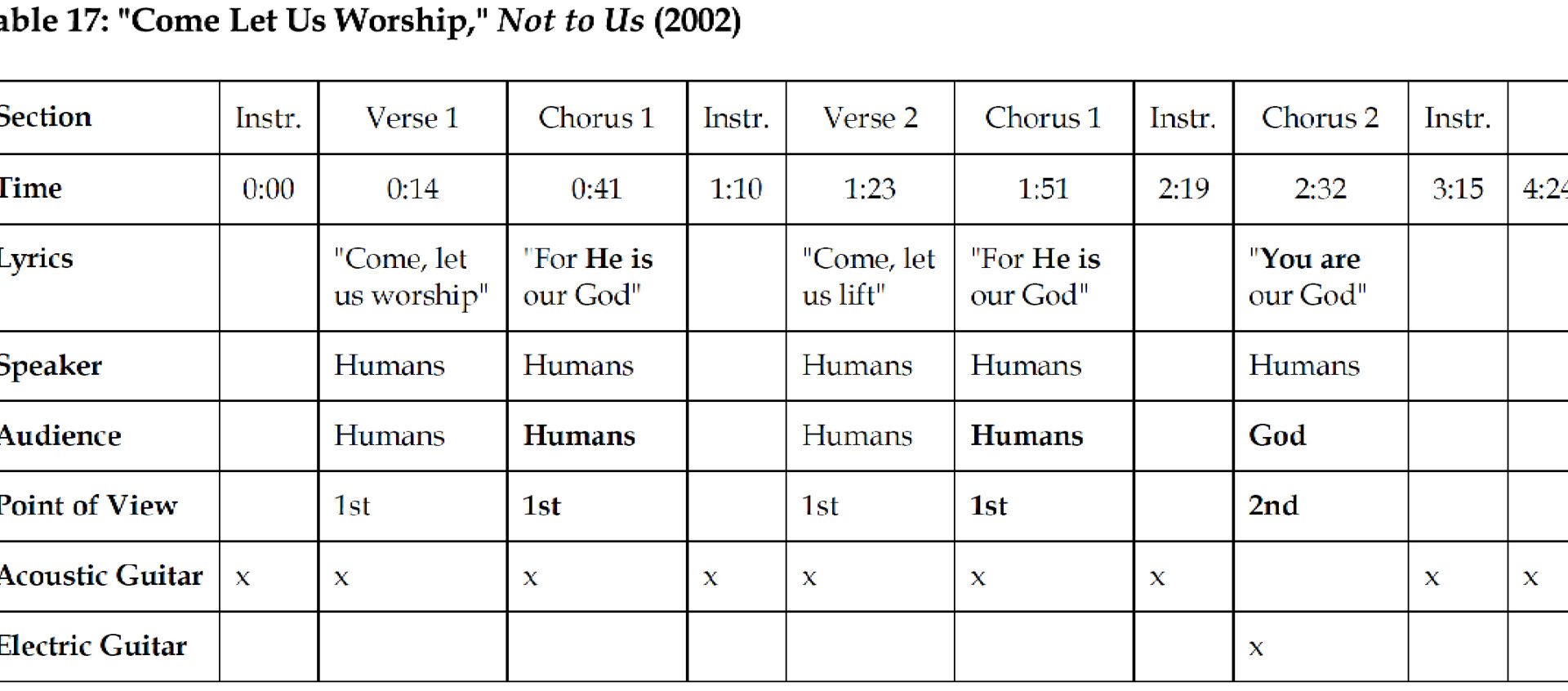

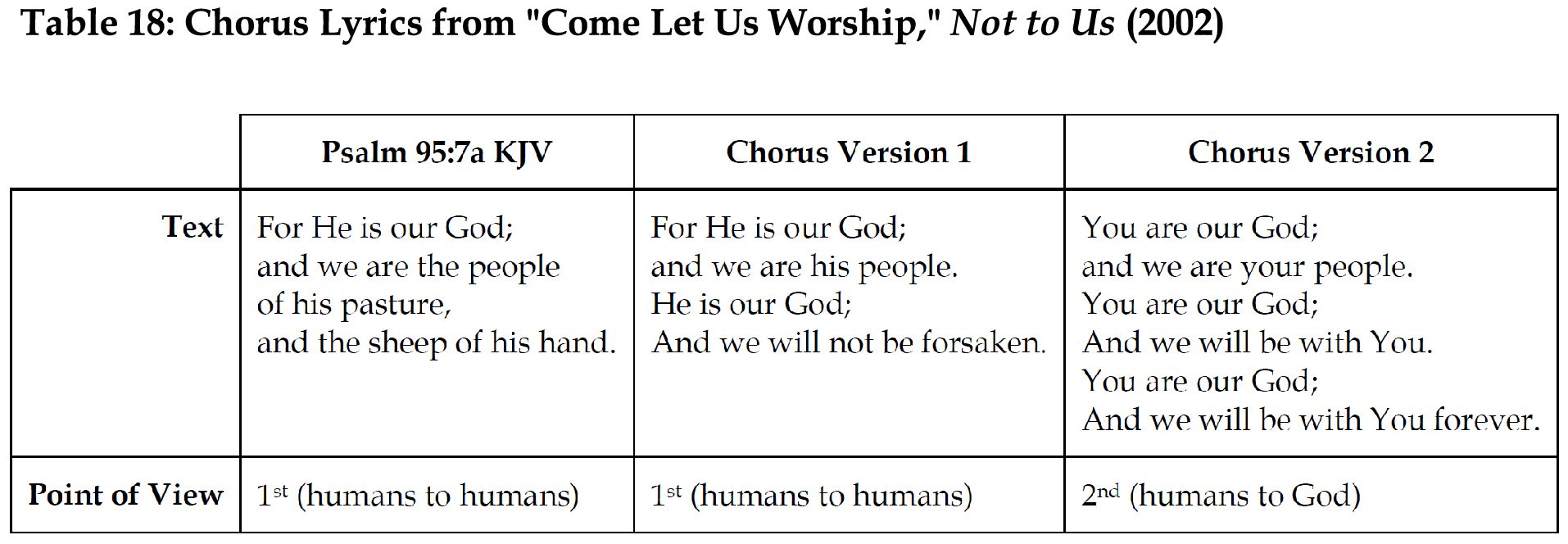

The second version of the chorus alters pronouns and verb tenses, repeats the second half, and, most significantly, replaces the negative “will not be forsaken” with the positive “will be with you forever.” Supporting the change in wording, both orchestration and form render the final statement of the chorus as the climax. Most of the song is fairly soft, foregrounding acoustic guitar. The last chorus, in contrast, is significantly louder, featuring distorted electric guitar and drum set. This climactic plateau is sharply delineated by the surrounding instrumental passages, which are far more contemplative in nature. The concluding instrumental passage lasts over a minute. This unusually long duration both represents and encourages medi- tation on “forever,” the final word of the song. The last chorus thus glimpses the future joy of worshiping God in eternity while acknowledging the perseverance needed for the present.

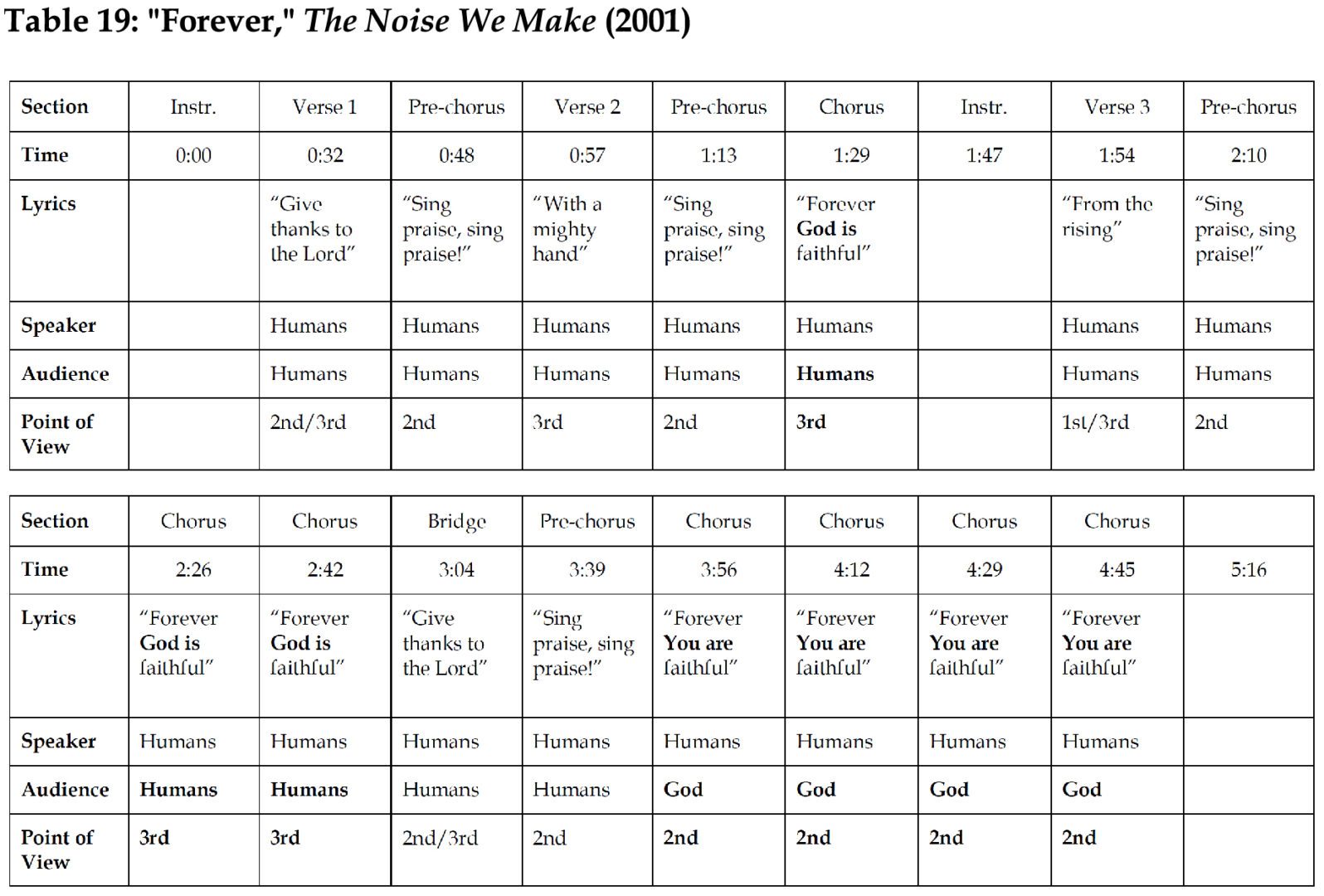

In contrast, the next example engages similar themes with a stronger sense of forward drive to and through the final section. “For- ever” combines a change in chorus lyrics with a formal deformation to emphasize a shift to speaking directly to God at the song’s end. Table 19 shows the form of the long version, which appears as track 2 on the 2001 album The Noise We Make. The form of the first half of the song is fairly conventional for Tomlin’s songs with three verses, delaying the chorus until after the second verse. The second half of the form, however, defies convention. Including two iterations of the chorus just before the bridge is uncommon. Including four iterations of the chorus at the end is unique in Tomlin’s output, placing even more weight than customary after the bridge.42 The unusual form mirrors the unusual text. Psalm 136 provides much of the song’s lyrics; the phrase “His love endures forever” that ends each biblical verse is included twice in each song verse. These verses integrate declarations in third person with instructions in second person, depict- ing humans speaking to humans throughout. The first version of the chorus declares “Forever God is faithful . . . strong . . . with us,” keep- ing the same speaker-audience pairing. The second version of the chorus, appearing as the block of four final statements, replaces “God is” with “You are.” Although involving few words, this alteration changes both the audience and point of view of the chorus. The text and the music together capture exuberant expectation of eternity. The shift in lyrics mirrors how worshipers in this life see only each other as they sing in hope, while worshipers in the next will see God. In addition to the unusual repetitions, two other musical features of the final block of choruses capture future expectation. While Tomlin sings the lead melody for most of the song, the accompanying gospel choir usurps this role in the final two iterations of the chorus, representing the multitudes singing to God. Furthermore, the song ends with a fade out, indicating how worship continues even beyond our ability to experience it now.

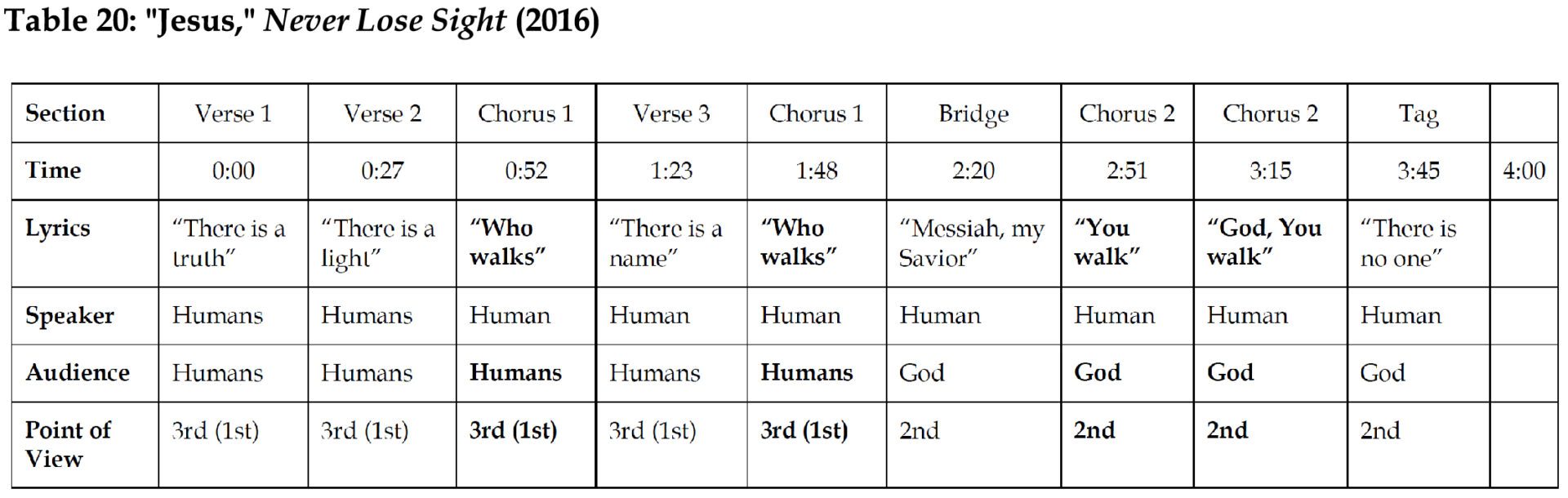

While the previous two songs use the modified chorus to drive the shift in point of view, “Jesus” from the 2016 album Never Lose Sight uses the modified chorus to sustain a shift that has already occurred. Table 20 shows how point of view bifurcates this song. Third person dominates the first half, with only occasional singular or plural first-person pronouns distracting from the list of Jesus’s at- tributes and actions from both the Old and New Testaments. For instance, the chorus describes him walking on water (Matthew 14:25– 33, Mark 6:47–52, John 6:16–21), standing in fire (Daniel 3, Isaiah 43:2), roaring like a lion (Hosea 11:10, Revelation 5:5), and bleeding like a lamb (Revelation 5:6). The bridge initiates the switch to second person, and the remainder of the song features a single human addressing God. The moment this occurs is highlighted by wording and orchestration. In stark contrast to the repetitions of “there is” in the verses, the bridge opens with the exclamation “Messiah, my Savior.” This climax in the lyrics is highlighted by a temporary silencing of most instruments, leaving acoustic piano in the foreground. The remainder of the song continues to address Jesus directly, using orchestration to regain energy. The drums and guitars reenter in the second half of the bridge only to drop out again at the first part of the modified chorus, highlighting the change from “Who” in the first version to “You” in the second. Orchestration gradually thickens, reaching the musical climax in the second and final statement of the modified chorus. Energy dissipates in the tag, concluding with the hushed statement “There is no one like you, Jesus.” This line combines the “there is” phrase from the verses with the second person point of view from the second half of the song. The dramatic arch of this song encapsulates both the motivation and experience of authentic worship, moving from declaration of truth to personal application to awestruck reverence.

In each of these examples, the second version of the chorus plays an important role in shifting attention from humans to God over the course of the song. Altering words allows the musical climax often found in the final statement of the chorus to take on new significance, communicating a shift in the attention and heart of the worshiper. Such songs attend first to the horizontal dimension before turning to the vertical dimension, reaffirming the value of Christian community before narrowing the focus to God alone.

Conclusion

Tomlin’s songs explore the gamut of relationships that triangulate God, an individual believer, and other humans. Some involve a stable pairing of speaker and audience. Those depicting a single individual singing to God—the type most in danger of reinforcing “mecentric” tendencies—constitute a relatively small percentage of Tomlin’s output. The remaining songs with stable pairings consistently use plural pronouns, reinforcing and normalizing the horizontal dimensions of fellowship and witness. Over half of Tomlin’s songs feature shifts in speaker, audience, or both. Such changes draw further attention to the interactions on both the vertical and horizontal planes. The dynamism of these shifts partially depends on the relationship between the lyrics and the music, as these songs harness form and style for expressive purposes. Naturally, incorporating a change in point of view does not singlehandedly guarantee the theo- logical, musical, or practical value of a given song. However, strategic shifts in speaker or audience can serve as a powerful reminder that the Christian life involves both the vertical connection to God and the horizontal connection to His people.

This case study demonstrates that most of Tomlin’s songs are far less self-absorbed than stereotypes of Contemporary Worship Music imply. Many are exemplary for the genre, simply yet effectively using form, range, and texture to shape and support biblical lyrics. This does not obviate legitimate criticism of individual songs and practices in CWM including excessive repetition, inappropriate romantic language, and elevation of the individual over the body of believers. It does, however, demonstrate the need for further corpus studies to facilitate discussions of the genre. The approach applied here to Tomlin’s output might profitably be applied to that of other artists or organizations such as Passion or Hillsong in order to ground claims about attributes and trends (whether read as positive or negative) in concrete statistics. Establishing this context further in- forms close analysis of the music and lyrics of individual songs, many of which can serve as creative and effective vehicles in corporate worship.

- Scott Aniol, By the Waters of Babylon: Worship in a Post-Christian Culture

(Grand Rapids: Kregel Publications, 2015), 158. ↩︎ - Joshua Kalin Busman, “(Re)Sounding Passion: Listening to American Evangelical Worship Music, 1997–2015” (PhD diss., University of North Carolina— Chapel Hill, 2015), 83–144, ProQuest (UMI 3703738). ↩︎

- Greg Scheer, The Art of Worship: A Musician’s Guide to Leading Modern Worship (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2006), 55. ↩︎

- While this claim may seem obvious to scholars of art song, arguments for or against Contemporary Worship Music (CWM) have often fixated on either lyrics or musical style, often ignoring or downplaying their interaction. While some condemnations of CWM pertain to the lyrics, far more focus on purely musical traits. As Busman summarizes, “the ‘worship wars’ centered on a question of the inherent spirituality or moral neutrality of specific musical forms. Opponents of the newer popularly-inspired music argued that the form of ‘rock and roll’ was not morally neutral and therefore was incapable of conveying a Christian message. But proponents of the music saw no moral content inherent within its form, arguing for its potential use as a powerful tool of Christian evangelism”; see Busman, “(Re)Sounding Passion,” 5. ↩︎

- “Past Winners,” GMA Dove Awards, Gospel Music Association, accessed December 18, 2018, https://doveawards.com/awards/past–winners/; “Artist: Chris Tomlin,” Recording Academy Grammy Awards, accessed December 18, 2018, https://www.grammy.com/grammys/artists/chris-tomlin. ↩︎

- Busman, “(Re)Sounding Passion,” 75–78 discusses Passion, its founder Louie Giglio, Tomlin’s involvement, and the associated record label sixstepsrecords, which was founded for artists associated with Passion. Also see this evangelical organization’s website: https://passionconferences.com/. ↩︎

- For a list of the one-hundred twelve songs that have appeared on CCLI’s top–25 lists from 1989 through February 2015, see Lester Ruth, “Some Similarities and Differences between Historic Evangelical Hymns and Contemporary Worship Songs,” Artistic Theologian 3 (2015): 79–80. Tomlin has recorded eight of these: “Amazing Grace (My Chains are Gone),” “Forever,” “Holy Is the Lord,” “Indescribable,” “Jesus Messiah,” “Joy to the World (Unspeakable Joy),” “Let God Arise,” and “Our God.” For an explanation of reporting cycles and the significance of CCLI’s list, see Robert Woods and Brian Walrath, eds., The Message in the Music: Studying Contemporary Praise and Worship (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2007), 19–20. ↩︎

- Matthew 22:37–39 KJV. Also see Mark 12:29–31 and Luke 10:26–27. ↩︎

- Monique M. Ingalls, “Awesome in this Place: Sound, Space, and Identity in Contemporary North American Evangelical Worship” (PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 2008), ProQuest (UMI 3328582), and Monique M. Ingalls, Singing the Congregation: How Contemporary Worship Music Forms Evangelical Community (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018). ↩︎

- Chris Tomlin, “HOLY ROAR: Doves & Armadillos . . . a Conversation with Christy & Nathan Nockels,” Things You May Not Know with Chris Tomlin: A Holy Roar Project, Podcast audio, November 9, 2018, Spotify, 34:25–34:32. ↩︎

- John Wimber, ed., Thoughts on Worship (Anaheim: Vineyard Music Group, 1996), 1–2; quoted in Wen Reagan, “A Beautiful Noise: A History of Contemporary Worship Music in Modern America” (PhD diss., Duke University, 2015), 245–46, ProQuest (UMI 3689059). ↩︎

- Scheer, The Art of Worship, 56–57. This passage also lists the less common options “humans to other beings” and “the worshiper speaks to himself or herself.” ↩︎

- Robert E. Webber, Worship Old & New: A Biblical, Historical, and Practical Introduction, revised ed. (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House, 1994), 118. This book provides an effective overview of how music and other elements in a worship service have changed over the centuries. ↩︎

- This chart uses the ordering of the Psalms included in most English translations of the Bible, which aligns with the Hebrew numbering rather than the Greek numbering. See the extensive database at https://hymnary.org/ for hymn texts and the long lists of hymnals in which the representatives appear. ↩︎

- Daniel Thornton confirms this in his study of twenty-five representative contemporary congregational songs, noting that “the majority . . . are from the personal/singular perspective.” He notes three exceptions in his corpus, two of which are Tomlin’s: “Our God” and “How Great Is Our God”; see Daniel Thornton, “Exploring the Contemporary Congregational Song Genre: Texts, Practice, and Industry” (PhD diss., Macquarie University, 2015), 105. ↩︎

- Recent editions of some hymnals likewise update pronouns where possible. Some modernizations go further, replacing or restructuring entire phrases and eliminating obscure imagery. ↩︎

- This shift impacted both lyrics and music: “Just as [Martin Luther] wanted the Bible to be in the German language, he also wanted the texts and the tunes of German church music to be in the vernacular”; Scott Aniol, Worship in Song: A Biblical Approach to Music and Worship (Winona Lake, IN: BMH Books, 2009), 64. ↩︎

- Scheer, The Art of Worship, 69. ↩︎

- Marva J. Dawn, Reaching Out without Dumbing Down: A Theology of Worship for the Turn-of-the-Century Culture (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1995), 96. ↩︎

- Ruth, “Some Similarities and Differences,” 74. ↩︎

- Scheer, The Art of Worship, 65–66. ↩︎

- One example is “Trading My Sorrows” (1998) by Darrell Evans, the chorus of which is dominated by repetitions of “yes, Lord” (2015), as mentioned in Tim Stewart, “7–11 songs,” Dictionary of Christianese, posted August 13, 2015, accessed September 4, 2019, https://www.dictionaryofchristianese.com/7-11-song/. ↩︎

- This is “a song whose lyrics express an overly romantic or love-sick devotion to Jesus,” as defined in Tim Stewart, “Jesus per minute, and Jesus is my girlfriend,” Dictionary of Christianese, posted August 5, 2012, accessed July 26, 2019, https://www.dictionaryofchristianese.com/jesus-per-minute-and-jesus-is-my- girlfriend/. Also see Scheer, Art of Worship, 69–71. For more extensive considerations of the romantic overtones of some CWM, see Jenell Williams Paris, “I Could Sing of Your Love Forever: American Romance in Contemporary Worship Music,” in The Message in the Music: Studying Contemporary Praise and Worship, ed. Robert Woods and Brian Walrath (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2007), 43–53; and Keith Drury, “I’m Desperate for You: Male Perception of Romantic Lyrics in Contemporary Worship Music,” in The Message in the Music: Studying Contemporary Praise and Worship, ed. Robert Woods and Brian Walrath (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2007), 54–64. ↩︎

- Reagan, “A Beautiful Noise,” 240. Also see the remainder of chapter 5 (223–64) for more information on Vineyard’s history and contributions to CWM. ↩︎

- Swee Hong Lim and Lester Ruth, Lovin’ on Jesus: A Concise History of Contemporary Worship (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2017). ↩︎

- See Paris, “I Could Sing of Your Love Forever,” 46; and Drury, “I’m Desperate for You,” 54–64. ↩︎

- Aniol, Worship in Song, 73. ↩︎

- Chris Tomlin, The Way I Was Made: Words and Music for an Unusual Life

(Sisters, OR: Multnomah Publishers, 2005), 53–54. ↩︎ - Gordon Adnams, “‘Really Worshipping’, not ‘Just Singing,’” in Christian Congregational Music: Performance, Identity and Experience, ed. Monique Ingalls, Carolyn Landau, and Tom Wagner (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2013), 196–97. Also see Gordon Adnams, “‘Here I Am to Worship’: Conflicting Authenticities in Contemporary Christian Congregational Singing,” Phenomenon of Singing 6 (2013): 22–29. ↩︎

- “What Is an Evangelical?” National Association of Evangelicals, accessed July 29, 2019, https://www.nae.net/what-is-an-evangelical/. ↩︎

- Ambivalence and ambiguity multiply further in considering the use of CWM in personal devotion. Even advertisements for worship music and resources emphasize the private individual over the public congregation; see Anna E. Nekola, “US Evangelicals and the Redefinition of Worship Music,” in Mediating Faiths: Religion and Socio-Cultural Change in the Twenty-First Century, ed. Michael Bailey and Guy Redden (New York: Routledge, 2016), 96–104. ↩︎

- Drury, “I’m Desperate for You,” 63. Scheer, The Art of Worship, 64 similarly stresses the need to write “from the ‘we’ perspective or the collective ‘I,’ but never in the first person without regard for the collective voice.” ↩︎

- Major streaming services including Spotify and Amazon Music currently include only the deluxe edition of Never Lose Sight but only the original release of Love Ran Red. This study uses these editions, reflecting the version listeners are most likely to access. ↩︎

- While many worship teams routinely add or omit repeats or sections of a given song in services, they often do so in reference to a particular recording. As Busman, “(Re)Sounding Passion,” 129 notes, “The rapid incorporation of Passion’s songs into the repertoires of individual congregations means that particular recordings of songs often become normative, not just through album sales or radio play, but also by serving as the urtext for the majority of weekly performances in local churches.” ↩︎

- This common pattern has more than one name in popular music scholarship. “Verse-chorus-bridge form” features in Ken Stephenson, What to Listen for in Rock: A Stylistic Analysis (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), 140–41. John Covach refers to the same structure as “compound AABA” in “Form in Rock Music: A Primer,” in Engaging Music: Essays in Music Analysis, ed. Deborah Stein (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 74–76. ↩︎

- For extensive surveys of rock stylistic traits ranging from form to harmony to texture, see Stephenson, What to Listen for in Rock mentioned above as well as David Temperley, The Musical Language of Rock (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018). ↩︎

- For an account of “We Fall Down,” see Chris Tomlin and Darren Whitehead, Holy Roar: 7 Words that Will Change the Way You Worship (Brentwood, TN: Bowyer & Bow, 2017), 76–79. ↩︎

- Tomlin and Whitehead, Holy Roar, 24–27. ↩︎

- Indeed, the practice of borrowing phrases from not only hymns but even other contemporary songs is commonplace, as noted in Thornton, “Exploring the Contemporary Congregational Song Genre,” 121. ↩︎

- Tomlin, The Way I Was Made, 166. While this quotation refers specifically to Hymns Ancient and Modern: Live Songs of Our Faith, an album excluded from this study, the core idea also applies to his other albums. ↩︎

- As in secular rock, “With regard to energy, we often find an increasing trajectory over the course of a song”; see Temperley, The Musical Language of Rock, 201. ↩︎

- To shorten this unusually long song, the “Forever Radio Remix” included as track 11 omits one of the verses and fades out during the third statement of chorus 2. ↩︎