Isaac Watts was a voluminous letter writer who corresponded widely with people on both sides of the Atlantic about a variety of topics. However, apart from an occasional reference, Watts’s surviving letters seldom mention his work in hymnody. Two important exceptions are a letter he wrote to his friend Samuel Say on March 12, 1709, asking for advice about the revision of his Hymns and Spiritual Songs and one to the New England Congregationalist minister Cotton Mather requesting a pre-publication critique of The Psalms of David Imitated in the Language of the New Testament (March 17, 1718).1

Another exception occurred during the period 1725–1726 when Watts carried on an extensive correspondence with a fellow Independent minister of London named Thomas Bradbury. These exchanges frequently referred to Watts’s writings of and about hymnody, and they shed light both on his views of his own work in this area and of critiques to which his publications were subjected.

Watts and Bradbury were almost exact contemporaries, and their lives and careers followed similar paths. Watts was born in 1674 and Bradbury in 1677. Both studied at academies run by Independent ministers, Watts at Newington Green and Bradbury at Attercliffe. Bradbury preached his first sermon in 1696, and Watts in 1698. Watts served as assistant pastor at the Mark Lane Independent chapel in London, became senior minister there in 1702, and remained as copastor at the church (which in the meantime had moved to Bury Street) until his death in 1748.2 Bradbury became an assistant or supply preacher in Leeds, Newcastle-on-Tyne, and Stepney (London), and was then chosen minister of the Independent congregation in New Street, London, in 1707, where he was ordained. He left the New Street church in 1728 and became pastor at the New Court Independent church. Bradbury died in 1759; both he and Watts were buried in Bunhill Fields, where many well-known dissenters were interred.

Bradbury was a frequent speaker at lectureships sponsored by Independents and was widely known as a preacher. He was also a controversial figure who was notorious for his outspokenness. Many of his sermons had a political cast to them, and some of these were considered to be “too violent” even “for men of his own party.”3 For instance, the nonconformist Daniel Defoe (author of Robinson Crusoe), writing anonymously (and deceptively) as “one of the people called Quakers” in A Friendly Epistle by Way of Reproof … to Thomas Bradbury (1715), calls Bradbury “a Dealer in Many Words” who “hast been busie in the Antichristian ungodly Work of Strife: Thou hast fallen upon the Innocent, with Words of Bitterness, engendering Malice and Envy, whereby thou hast been the Occasion of much Evildoing, and hast brought forth Wrath among thy Brethren.”4 Bradbury was particularly vocal about the doctrine of the Trinity, becoming one of the leaders of a group of Independent ministers who, at Salter’s Hall in 1719, subscribed to the first of the Thirty-Nine Articles of the Church of England and the fifth and sixth answers of the Westminster Shorter Catechism; both documents emphasized the orthodox view of the unity of the Godhead and the three-fold personhood of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The non-subscribers mostly held the same views but preferred for the matter to be left to “Christian liberty.”

In addition to his blunt speaking and writing, Bradbury exhibited an uncommon sense of humor, or, as some of his contemporaries expressed it, “levity.” This attribute of Bradbury was noted by the writer of Christian Liberty Asserted (1719), identified only as “a Dissenting Lay-Man,” who called Bradbury “abundantly Witty” and accused him of “unallowable Levity” that is “much beneath a Gospel Minister.”5 Isaac Watts and Thomas Bradbury probably became acquainted soon after the latter’s arrival in London in 1703. They certainly knew one another by 1709, when Watts published the second edition of his Horæ Lyricæ, for the book included a six-stanza poem titled “Paradise” that was dedicated “To Mr. T. Bradbury.” Writing from the perspective of a person who has already gone to heaven, Watts, like the “Dissenting Lay-Man,” gives a hint of Bradbury’s “levity.”

I long’d and wish’d my BRADBURY there;

“Could he but hear these Notes, I said,

His tuneful Soul wou’d never bear

The dull unwinding of Life’s tedious Thread,

But burst the vital Chords to reach the happy Dead.”6

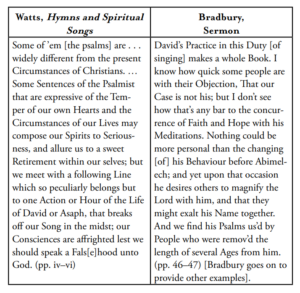

“Tuneful soul” perhaps suggests an interest in music and song, and, indeed, that also appears to have been a part of Bradbury’s make-up. Perhaps this interest is partly the reason he was invited to preach (and subsequently print) a sermon in a series by various Independent ministers that appeared in 1708 as Practical Discourses of Singing in the Worship of God.7 Bradbury’s sermon was titled “Arguments for the Duty of Singing.” While Watts would have agreed with much of what Bradbury said in this essay, he would probably have been taken aback by a few statements that sound like direct contradictions of expressions in Watts’s Hymns and Spiritual Songs, first published in the previous year (1707), as compared in the following table.

These contrasting views give a hint of what lay in the future between the two men, but whatever Watts might have thought about Bradbury’s comments—of which he was certainly aware since he owned a copy of Practical Discourses—it did not stop him from dedicating the Horæ Lyricæ poem to his fellow minister in the following year and continuing to publish it in later editions.8

THE RUPTURE

Unfortunately, whatever friendship existed between Watts and Bradbury did not survive Watts’s writings of 1719 and following. Though other issues were also involved, the disagreement between the two men centered primarily on two subjects, Watts’s writings on the doctrine of the Trinity and his belief that the psalms were unsuitable for Christians to sing without alteration or “Christianization.” In 1719 Watts published the first edition of The Psalms of David Imitated, bringing into being the kind of “Christianized psalms” for which he had advocated in Hymns and Spiritual Songs.9 In 1722 he issued The Christian Doctrine of the Trinity: or Father, Son, and Spirit, Three Persons and One God, Asserted and Prov’d, following this two years later with Three Dissertations Relating to the Christian Doctrine of the Trinity, then a second part to the latter book in 1725.10 Watts’s expressed purpose in these writings on the Trinity was “to lead such as deny the proper Deity of Christ, into the Belief of that great Article”;11 indeed, one of the Three Dissertations was titled “The Arian invited to the Orthodox Faith.” While these writings naturally provoked responses from persons who rejected Trinitarian doctrine, they also caused a reaction from people in orthodox Trinitarian circles, including Thomas Bradbury, who considered them to lean too far toward Arianism in their attempt at conversion of the sceptic.12 As noted above, Watts and Bradbury had publicly expressed divergent views about the psalms in 1707–1708, but it was apparently Watts’s publication of The Psalms of David Imitated and his books on the Trinity that drew Bradbury into renewed public objection to Watts’s view and treatment of these subjects.

Bradbury’s criticism, expressed both in speech and print, was taken by Watts as a personal attack and led to an increasingly harsh exchange of eleven letters, with misunderstandings and recriminations on both sides.13 While the disagreement was unpleasant, it did have the result of bringing out comments from Watts on his own writing of and about hymnody. As noted earlier, these statements are among the few extant direct references he made to his texts outside the publications in which they appeared and thus are of considerable interest.

THE LETTERS

The correspondence began on February 26, 1725, when Watts wrote to Bradbury, addressing him as “Dear Brother,” though claiming that Bradbury’s “late conduct in several instances seems to have renounced the paternal bonds and duties of love.”14 “Among other things,” Watts says,

I could not but be surprized [sic] that you should fall so foul both in

preaching and in print upon my books of Psalms and Hymns; when,

while I was composing the Book of Psalms, I have consulted with you

particularly about the various metres, and have received directions

from you in a little note under your own hand, which was sent me

many years ago by my brother, wherein you desired me to fit the fiftieth

and one hundred and twenty second Psalms to their proper metre:

though I cannot say that I am much obliged to you for the directions

you then gave me, for they led me into a mistake in both those Psalms

with regard to the metre, as I can particularly inform you if desired.15

Watts goes on to point out that Bradbury’s falling “foul both in preaching and in print” on his psalms and hymns refers at least partly to Bradbury’s most recent book of sermons, The Power of Christ over Plagues and Health (1724). In the preface to that volume, Bradbury named Watts as his “dear and worthy Friend” but confessed that he “was rather amazed than allured” by some of the analogies Watts used in Three Dissertations in trying to explain the Trinity. In the seventh sermon, Bradbury—without naming Watts—critiqued the hymn writer’s views on singing the psalms by claiming that he cannot

be brought to believe, by all that I have read upon the Argument, that

the Devotion of the one [Testament] is not evangelical enough for the

other. David speaks in a way becoming Saints. The Supposition that

his Psalms are too severe and harsh, and not proper for a Christian

Assembly, and putting into his Mouth a Sett of Words that Man’s

Wisdom teaches, argues an Inadvertency to what [he] himself has told us,

That the Spirit of the Lord spake by me, and his Word was in my Tongue.

The Writings of the Prophets are design’d to be our Rule, as well as those

of the Apostles. To say that the Imprecations in the Psalms are offensive

to Christian Ears, is talking with a Boldness that I dare not imitate.

Morality is the same now that it ever was, and I cannot think that the

Holy Spirit has made that Language Divine in the Old Testament,

which is uncharitable in the New. We have no new Commandment, but

what was deliver’d to us from the Beginning. And I look upon several

Phrases in the New Testament to be as harsh as those in the Old, if we

must call any thing so that God has revealed.16

For Watts, the critical mention by Bradbury of his book on the Trinity without a discussion of the specific points of disagreement, plus the thinly veiled reference to his views on the psalms and the claim that he had put into David’s mouth “a Sett of Words that Man’s Wisdom teaches,” constituted a personal and very public attack to which he apparently felt he must respond.

Watts’s letter either went unanswered or Bradbury’s response has been lost, for the next letter, dating from November 1, 1725, is again from Watts to Bradbury.17 The letter begins in a friendly enough manner with thanks for a favor Bradbury had done for a friend. But then Watts goes on to criticize Bradbury for a letter the latter had written around the beginning of the previous June to an Independent board of which Watts was a member. According to Watts, the missive contained “censures” upon him and other board members, and Bradbury’s “conduct” since that time was also considered unsuitable.18 What exactly these “censures” and “conduct” were is not said, and there is no mention of hymnody in Watts’s letter.

Bradbury responded to this second letter from Watts on December 23, 1725, indicating that it was never his intent to cast personal aspersions on Watts. “I call you the best divine poet in England,” he said, “and the liberty you have taken with David’s Psalms, affirming ‘that they are shocking to pious ears,’ is a harsher phrase than I ever used of you.” Still, he acknowledges “that my adherence to the things that I have learned and been assured of, has made me think in a very different way from what you have now printed, both about the Psalms and the son of David.”19 But then he pours fuel onto the fire.

I can assure you, I am not behind-hand in hearty wishes . . . that your

poetical furniture [i.e., adornments] may never make you suppose that

the highest of human fancy is equal to the lowest of a divine inspiration;

that you will learn to speak with more decency of words that the Holy

Ghost teaches, and less vanity for your own, and never rival it with

David, whether he or you are the sweet psalmist of Israel.20

As might be expected, the last clause of the quotation called forth a strong rejoinder from Watts in a letter of January 24, 1726.

You tell me that “I rival it with David, whether he or I be the sweet

psalmist of Israel.” I abhor the thought; while yet at the same time I

am fully persuaded, that the Jewish psalm book was never designed to be

the only psalter for the christian [sic] church; and though we may borrow

many parts of the prayers of Ezra, Job and Daniel, as well as of David,

yet if we take them entire as they stand, and join nothing of the gospel

with them, I think there [are] few of them [that] will be found proper

prayers for a christian church; and yet I think it would be very unjust

to say, “we rival it with Ezra, Job, &c.” Surely their prayers are not

best for us, since we are commanded to ask every thing in the name of

Christ. Now, I know no reason why the glorious discoveries of the New

Testament should not be mingled with our songs and praises, as well

as with our prayers. I give solemn thanks to my Saviour, with all my

soul, that he hath honoured me so far, as to bring his name and gospel

in a more evident and express manner into christian psalmody.21

Watts then reiterates what he had said in his first letter to Bradbury of

nearly a year before.

. . . did I not consult with you while I was translating the psalms in

this manner, fourteen or fifteen years ago? Whether I was not

encouraged by you in this work, even when you fully knew my design,

by what I had printed, as well as by conversation? Did you not send me

a note, under your own hand, by my brother, with a request, that I

would form the fiftieth and the hundred and twenty-second psalms into

their proper old metre? And in that note you told me too, that one was

six lines of heroic verse, or ten syllables, and the other six lines of shorter

metre: by following those directions precisely, I confess I committed a

mistake in both of them, or at least in the last; nor had I ever thought

of putting in those metres, nor considered the number of the lines, nor

the measure of them, but by your direction, and at your request.22

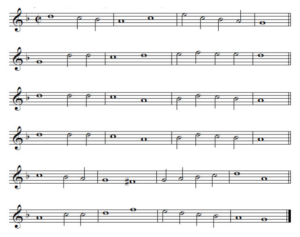

The “mistakes” into which Watts was led by following Bradbury’s advice can be readily discerned. If Bradbury indeed told him that the “proper old metre” for Psalm 50 was six lines of ten syllables, he was in error, since the traditional tune for that psalm has the line/syllable count 10.10.10.10.11.11 (Ex. 1).23

Example 1. PSALM 50 OLD from John Playford, The Whole

Book of Psalms, 7th ed. (London, 1701).

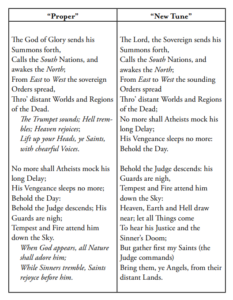

It is likely that Watts first wrote his six-line, ten-syllable paraphrase of Psalm 50, “The Lord, the sovereign, sends his summons forth,” in response to Bradbury’s suggestion, then, realizing that it would not fit the “old proper tune,” revised it into “The God of glory sends his summons forth,” with its four ten-syllable and two eleven-syllable lines; the two paraphrases are essentially the same text but Watts added a two-line refrain to “The God of glory” to account for the eleven-syllable lines (Ex. 2).24 Watts opted to print both versions in The Psalms of David Imitated, with “The God of glory sends his summons forth” calling for PSALM 50 OLD and “The Lord, the sovereign” for “a new tune.”

Example. 2. Stanzas 1–2 of Watts’s “Proper” and “New Tune”

versions of Psalm 50 from the first edition of The Psalms of David

Imitated (1719).

The proper tune for Psalm 122 follows the pattern 668668D but Watts, again evidently relying on Bradbury’s advice, wrote “How pleas’d and blest was I” in five 668668 stanzas, which means there would either be an “extra” stanza left over after the tune was completed twice or only the first half of the tune would be sung with the last stanza. In the second edition of The Psalms of David Imitated (published later in 1719) Watts corrected this problem by including a note to “Repeat the 4th Stanza to compleat the Tune,” thus giving the text an even number of stanzas.25

Bradbury responded to Watts three days later (January 27) and the exchange grew even more heated. He asked if Watts believed that the latter’s passages “on the Trinity or Psalmody” that he had criticized were the only ones “that have stumbled me and many others.” “No,” he said, “I had my affliction almost in every page; and as mean as my abilities are, I always thought them sufficient to shew, that you had departed from the plain text of scripture, and allowed yourself in dangerous vagaries of human invention.”26 Later in the letter Bradbury critiques Watts’s writings about psalmody and explains his intentions regarding his earlier encouragement of Watts in making versions of the psalms.

Your notions about psalmody, and your satyrical [sic] flourishes in

which you have expressed them, are fitter for one who pays no regard

to inspiration, than for a gospel minister, as I may hereafter shew in

a more public way.But I must tell you, there is hardly any foundation for what you say

about my encouraging that work fifteen years ago. I was glad to hear

that your thoughts were turned to a translation of David’s Psalms; I

thought it was a good evidence that you begun to come in to them,

as others do; that they are not of private interpretation, but what God

designed for his churches under the New Testament. In order therefore

to make your work more useful, I desired you to put in two measures

which Dr. [John] Patrick has omitted, because we have admirable

tunes fitted to them.

Bradbury then attacks Watts’s method of paraphrasing the psalms: “But you are mistaken if you think I ever knew, and much less admired, your mangling, garbling, transforming, &c. so many of your songs of Sion; your preface to your work is of the same strain with what you had writ before [i.e., in Hymns and Spiritual Songs]; and if I remember that, you had my opinion very freely, in company with the late Mr. Thomas Collings.”27

Watts, of course, could not let the matter stand there. In his February 2, 1726, reply, he told Bradbury that “I easily believe, indeed, that your natural talent of wit is richly sufficient to have taken occasions from an hundred passages in my writings to have filled your pages with much severer censures.” He goes on to say (perhaps with tongue in cheek) that “In the vivacity of wit, in the copiousness of style, in readiness of scripture phrases, and other useful talents, I freely own you far my superior, and will never pretend to become your rival,” then defends himself against the “satyrical flourishes” charge.

I know not of any thing in all my writings on the subject of psalmody

that can deserve the name of a “satyrical flourish,” unless it be one

sentence in the Appendix to my first edition of Hymns, which was

written near twenty years ago, and should have been revoked or

corrected long since, had I ever reprinted it; and therefore I shall by no

means support or defend that expression now.28

The appendix to which Watts refers was “A Short Essay Toward the Improvement of Psalmody: Or, An Enquiry of how the Psalms of David ought to be translated into Christian Songs, and how lawful and necessary it is to compose other Hymns according to the clearer Revelations of the Gospel, for the Use of the Christian Church.” In the second edition of Hymns and Spiritual Songs Watts left out the “Short Essay” “partly lest the Bulk [of the book] should swell too much, but chiefly because I intend a more compleat Treatise of Psalmody”; this “compleat Treatise of Psalmody” was never published and the “Short Essay” was never reprinted, though some of its arguments reappeared in the preface to The Psalms of David Imitated.29 Watts did not identify in this letter the sentence that contained the “satyrical flourish” but the passage is made explicit in later correspondence, as will be seen below. Surprisingly, Watts did not respond to Bradbury’s charge about his “mangling, garbling, transforming, &c.” the psalms.

In his reply of March 7, 1726, Bradbury indicates that “What you say about my talent for ‘satyrical flourishes’ may be true . . . but I never used them upon the Psalms of David, or any of the words that the Holy Ghost has taught. I durst not be so merry as you have been with a book that was ever received as a treasure of all divine experience.”30 He then quotes (and partly misquotes) a passage from Watts’s “Short Essay” in which the hymnwriter points out passages in the psalms that the “unthinking Multitude” sing “in cheerful Ignorance”; Bradbury calls Watts’s words a “lampoon.”

. . . (the people) “follow with a chearful ignorance, whenever the

clerk [i.e., the song leader] leads them across the river Jordan, through

the land of Gebal and Ammon, and Amalek, he takes them into the

strong city, he brings them into Edom, anon they follow him through

the valley of Baca, till they come up to Jerusalem; they wait upon him

into the court of burnt offering, and bind their sacrifice with cords to the

horns of the altar; they enter so far into the temple, till they join their

songs in concert with the high-sounding cymbals, their thoughts are

bedarkened with the smoke of incense, and covered with Jewish veils.”

Should any one take the liberty of burlesquing your poetry, as you

have done that of the most high God, you might call it “personal

reflection,” indeed.31

Bradbury next proceeds to point out “that most of these expressions [in the psalms] are adopted either by the New Testament, or the Evangelical Prophets.”32 But that is not the end of the critique.

This is not the only offensive passage in the book; I have observed

almost one hundred. And though it is left almost entirely of the same

complexion in your later editions, yet that nothing might be lost, you

have taken care to tell your readers, that they shall be gathered up again

in your Treatise of Psalmody; these are your “satyrical flourishes” that

I complained of.

Finally, in a sentence that was guaranteed to raise Watts’s hackles, Bradbury suggests that “You have shewn a thousand times more meekness to an Arian, who is the enemy of Jesus, than you have done to king David who sung his praises.”33 His statement is perhaps a reflection of one by Watts himself in his Three Dissertations: “Some think, That I do not write with Indignation and Zeal enough, and that I treat the Adversaries of the Divinity of Christ with too much Gentleness for any Man who professes to be a Friend to that Sacred Article, and a Lover of the Blessed Saviour” (p. xv).

Watts’s return letter (March 15, 1726) acknowledges that the extract Bradbury quoted from the “Short Essay” is the one he would have retracted had he ever republished the writing, saying “I now condemn it.”34 In a postscript he points out what he believes are “personal reflections” on him (as opposed simply to differences of opinion), including the charge of “‘burlesquing the poetry of the most high God:’ whereas I only shewed the impropriety of using even inspired forms of worship, peculiarly Jewish, in Christian assemblies, and assuming them as our songs of praise to God; though I have confessed to you that I condemn the manner in which I have expressed it in the offensive sentence which you cite.” He also quotes Bradbury’s statement about showing “a thousand times more meekness to an Arian, who is an enemy of Jesus, than I have done to king David” as an example of “personal reflection.”35

On March 17, 1726, Bradbury wrote that, while he had been “offended” over Watts’s “notions about psalmody, and the personality of Christ Jesus” and had “delivered” himself “upon those subjects, when they came in my way,” this was not “done with indignity to your character, or hatred of your person.”36 Later, Bradbury expresses his gladness that Watts now rejects the phrase in the “Short Essay” “that has been so wounding to me” and suggests that “a public retraction” would be in order, though how this would be done is difficult to see since the essay was never reprinted.

Unfortunately, Bradbury could not leave it at that, for he goes on to say, “I read with terror your assertion, that the Psalms of David are shocking to pious ears. Such a notion as that lets in deism like a flood: but I will not debate this matter in private epistles.”37 Where Bradbury encountered the phrase about the psalms being “shocking to pious ears” is unknown, since that wording does not appear in either Hymns and Spiritual Songs or The Psalms of David Imitated, nor, so far as I have been able to determine, in any other works by Watts. About the closest Watts ever came to printing something like that was in Hymns and Spiritual Songs, where he says that some of the psalms “are almost opposite to the Spirit of the Gospel” and begs leave “to mention several Passages [in the psalms] which were hardly made for Christian Lips to assume without some Alteration,”38 but these statements are a long way from calling them “shocking to pious ears.” In fact, the first use of this phrase that has been located is in Bradbury’s own letter of December 23, 1725, quoted above, where he also attributes these words to Watts.

“I am quite tired with this epistolary war (as you please to call it),” Watts wrote on March 18, 1726, in one of the shortest letters of the exchange. He went on to say, “I desire this letter may entirely finish it.”39 Given Bradbury’s tenacious nature, that was a forlorn hope, and, on March 22, Bradbury addressed to Watts another lengthy complaint from “your abused and injured brother.”40 Neither of these messages make any mention of congregational song. The trading of letters between the two men seems to have ended after this writing from Bradbury, with Watts—who in one of them confessed that he had “more important affairs that demand the few hours wherein I am capable of applying myself to read or write”41 — tiring of the situation and Bradbury probably feeling that he had gotten in the last word.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Several aspects of the exchange of letters call for additional comment. One is that neither man appears in a particularly positive light. While the letters are often couched in a polite tone, this is stiffly formal and is frequently counterbalanced by accusations and retaliations. Misunderstandings abound, and the letters are often parsed by the receiver to give them a derogatory reading that may not have been intended by the sender. The letters began as an attempt to protest “personal reflections,” but the longer the correspondence went on the more personal and vehement the reflections became on both sides.

Another feature of the letters is that Bradbury’s criticisms of Watts’s views on the psalms are almost entirely responses to passages from Hymns and Spiritual Songs, and especially to the “Short Essay” from that book. Indeed, the only time he refers directly to the published version of The Psalms of David Imitated is in his letter of January 27, 1726, when he calls Watts’s work a “mangling, garbling, transforming, &c.” of the psalms and mentions that Watts’s preface to that book “is of the same strain with what you had writ before.” This emphasis upon the “Short Essay” is surprising, since that work was nearly twenty years old at the time of the letters and had never been reprinted. The exchange also shows that Watts’s views of and work on the psalms were not universally admired.

The correspondence provides further evidence of Watts’s authorial humility and willingness to receive constructive criticism of his hymns. As noted above, he had sought advice from friends and correspondents about the second edition of Hymns and Spiritual Songs and the first edition of The Psalms of David Imitated. His letters to Bradbury likewise reveal this readiness to accept and implement advice, even when following it led to “mistakes.” But the correspondence also indicates his unwillingness to let what he considers to be unjust attacks on his hymns go unchallenged. In addition, the letters show the reasons for his unusual six-line, ten-syllable version of Psalm 50 and his misjudgment in the meter of Psalm 122, both cases resulting either from incomplete advice on Bradbury’s part or a misunderstanding of that advice by Watts.

Finally, the correspondence affirms Watts’s estimation of his own work. In the seventh edition of Hymns and Spiritual Songs (1720) he had indicated his belief that that book, plus The Psalms of David Imitated, were “the greatest Work that ever he has publish’d, or ever hopes to do, for the Use of the Churches.”42 His January 24, 1726, letter shows that he had not changed his mind, as he unapologetically gives “solemn thanks” that he has been “honoured” to bring Christ’s “name and gospel in a more evident and express manner into christian psalmody,” and reiterates one of his primary goals: that the songs of the Christian church should reflect the gospel message as expressed through the New Testament. That Watts’s pride in his work was not misplaced is evident from the widespread use his hymns and psalm versions have received in the ensuing 300 years. In the end, while Bradbury might have gotten the last word in the correspondence, Watts got the last word in the singing practice of English-speaking congregations, a last word that is still being sung today.

- The replacement of church choirs with contemporary worship ensembles has often led to the abandonment not only of Sunday-by-Sunday choral music but also the absence of major choral works in many American churches. ↩︎

- Thurston J. Dox, American Oratorios and Cantatas: A Catalog of Works Written in the United States from Colonial Times to 1985, 2 vols. (Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1986). ↩︎

- See John Mark Jordan, “Sacred Praise: Thomas Hastings and the Reform of Sacred Music in Nineteenth-Century America” (PhD diss., Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, 1999), for a comprehensive discussion of Hastings’s writings on church music. Other important studies of Hastings and his music are Mary Browning Scanlon, “Thomas Hastings,” The Musical Quarterly 32, no. 2 (April 1946), 265–77; James E. Dooley, “Thomas Hastings: American Church Musician” (PhD diss., Florida State University, 1963); and Hermine Weigel Williams, Thomas Hastings: An Introduction to His Life and Music (New York: iUniverse, 2005). ↩︎

- The named texts are the ones with which Hastings first published the tunes. Other texts have been used with each of these melodies. ↩︎

- Musica Sacra: a collection of psalm tunes, hymns and set pieces, 2nd ed., rev. and corr. (Utica, NY: Seward & Williams, 1816); Christian Sabbath and Nativity Anthem; Together with a Few Other Pieces of Sacred Music (Utica, NY: Seward and Williams, 1816). ↩︎

- See my introduction to Thomas Hastings: Anthems, Recent Researches in American Music 83 (Middleton, WI: A-R Editions, 2017), viii, for a discussion of the somewhat confusing publication history of the first edition. It appears that when the two pamphlets were combined in 1816 to make up the first complete edition of the tune book, Hastings simply reused the title page from the first pamphlet, which probably appeared in late 1815. ↩︎

- Hastings apparently never published The Christian Sabbath and Pressburgh again after their appearances in the appendix to the second edition of Musica Sacra and the pamphlet. ↩︎

- I am grateful to Allen Lott for pointing out the Southwestern Seminary copies of the pamphlets to me and providing me with relevant material from them. ↩︎

- Williams, Thomas Hastings, 20. ↩︎

- Jeremy Belknap, Sacred Poetry. Consisting of psalms and hymns, adapted to Christian devotion, in public and private (Boston: Apollo Press, 1795), preface; Watts’s hymn appears on pp. 282–83. In Sacred Poetry, the new line in stanza 4 reads “Till it is call’d to soar away.” ↩︎

- See the section “Of Fugue and Imitation” in Thomas Hastings, Dissertation on Musical Taste, rev. ed. (New York: Mason Brothers, 1853), 149–53. ↩︎

- For example, in Hastings’s opinion, fugues in vocal music of the past have “done extensive injury, by the confusion of words they have occasioned” (“Different Departments of Music. No. XV,” Western Recorder, October 24, 1826). ↩︎

- Settings of prose texts are generally called “anthems,” while through-composed settings of poetry are “set pieces.” ↩︎

- Karl Kroeger, ed., Early American Anthems. Part I: Anthems for Public Celebrations, Recent Researches in American Music 36 (Madison, WI: A-R Editions, 2000), xiii; Merrill’s anthem appears on pp. 31–58. Kroeger’s introduction provides a useful summary of the typical features to be found in American anthems of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. ↩︎

- For examples of some of these secular works, see under “cantata” in the indexes of O. G. Sonneck, A Bibliography of Early Secular American Music (Washington, DC: H. L. McQueen, 1905; rev. and enl. by William Treat Upton, New York: Da Capo Press, 1964), and Richard J. Wolfe, Early Secular Music in America, 1801–1825: A Bibliography (New York: New York Public Library, 1964). See O. G. Sonneck, Early Concert-Life in America (1731–1800) (Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1907; reprint, New York: Da Capo Press, 1978), for newspaper reports of cantata performances in eighteenth-century America. ↩︎

- On page x of American Oratorios and Cantatas, Dox observed that “in the eighteenth century, the term ‘cantata’ was applied to accompanied works for soloists, with vocal ensembles or chorus. Both sacred and secular texts were used.” However, the specific designation “cantata” for a piece of sacred music appears to have been relatively uncommon and was certainly rare in early America. The pre-1816 American sacred pieces listed in Dox’s bibliography either were not called cantatas by their composers or (as far as can be discovered) by their contemporaries, or their dates of composition and/or performance are not known. ↩︎

- New-York Daily Advertiser (December 15, 1817). The term “oratorio” was often used in early nineteenth-century America to indicate a miscellaneous concert, not necessarily a single major work (such as an oratorio by Handel). The recitative-aria pair by Phillipps was listed in the advertisement as “And have I never praised the Lord” and “Praise the Lord,” respectively. The Orange County Patriot of November 18, 1817, reported that Thomas Phillipps had “recently arrived in New-York from Europe.” ↩︎

- The Heav’ns Declare” was printed in Selby’s serialized publication Apollo and the Muses (1791), and Gram’s “Bind Kings with Chains” appeared in Laus Deo! The Worcester Collection of Sacred Harmony, 5th ed. (1794). For a description of Selby’s piece, see Nicholas Temperley, Bound for America: Three British Composers (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2003), 38–40. An unusual feature of “Bind Kings with Chains” is the presence of a “Largo Recitativo” for bass soloist and an instrumental bass. The “Dirge, or Sepulchral Service” was published anonymously in Boston in 1800; the known copies are bound with Sacred Dirges, Hymns, and Anthems, commemorative of the death of General George Washington (Boston, [1800]). The attribution to Holden appears in contemporaneous newspaper sources. A modern edition of the work is available in Oliver Holden (1765-1844): Selected Works, Music of the New American Nation 13, Karl Kroeger, gen. ed. (New York: Garland Publishing, 1998), 183–90. ↩︎

- David Moritz Michael, Der 103te Psalm: An Early American-Moravian Sacred Cantata for Alto, Tenor, and Bass Soloists, Mixed Chorus, and Orchestra (1805), ed. Karl Kroeger, Recent Researches in American Music 65 (Middleton, WI: A-R Editions, 2008). Michael’s work is listed in Dox’s bibliography as CA2143. ↩︎

- See Thurston Dox’s articles “Samuel Felsted of Jamaica,” The American Music Research Center Journal 1 (January 1991): 37–46, and “Samuel Felsted’s Jonah: The Earliest American Oratorio,” Choral Journal 32, no. 7 (February 1992): 27–32. In 1994, Hinshaw Music published a performing edition of Jonah, edited by Dox. ↩︎

- The Boston Handel and Haydn Society had been founded only the year before publication of Hastings’s cantata (1815) and is still an active organization. The New York Handel and Haydn Society was founded in 1817 but gave its last concert in 1821; see Dennis Shrock, Choral Repertoire (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 546, and Vera Brodsky Lawrence, Strong on Music: The New York Music Scene in the Days of George Templeton Strong, vol. 1 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), xxxviii. ↩︎

- Posthumous Works, 2:182. ↩︎

- Posthumous Works, 2:182–83. ↩︎

- The refrain is unlike most such devices in that it does not repeat verbatim after each stanza. Instead, it uses a variety of repetitions, alterations, and single statements. ↩︎

- Watts also used the traditional Ps. 50 proper meter in a paraphrase of Ps. 93 (“The Lord of glory reigns; he reigns on high”), and the Ps. 122 meter for another version of Ps. 93 (“The Lord Jehovah reigns”) and one of his renditions of Ps. 133 (“How pleasant ’tis to see”); all these versions likewise had to be corrected in subsequent editions of The Psalms of David Imitated. The “new tune” meter of Ps. 50 was employed again for Ps. 115. A melody and bass line to fit Watts’s “new tune” version of Ps. 50 was published in William Lawrence’s A Collection of Tunes, Suited to the Metres in Mr. Watts’s Imitation of the Psalms of David, or Dr. Patrick’s Version (London: W. Pearson for John Clark, R. Ford, and R. Cruttenden, 1719), which probably appeared shortly after the first edition of The Psalms of David Imitated. See David W. Music, Studies in the Hymnody of Isaac Watts (Leiden: Brill, 2022), 206–9. ↩︎

- Posthumous Works, 2:186. It is not entirely clear whether Bradbury is referring primarily to Watts’s writings on the Trinity, psalmody, or both, though the first-named seems most likely. ↩︎

- Posthumous Works, 2:189. The public critique of Watts’s “satyrical flourishes” Bradbury hinted at in his letter apparently never came to fruition. The book by John Patrick he mentioned was A Century of [i.e., 100] Select Psalms, first published in 1679 and subsequently enlarged into a complete psalter.

↩︎ - Posthumous Works, 2:193. Though written in early February, Watts’s letter was not sent until a month later (see p. 191). ↩︎

- I. Watts, Hymns and Spiritual Songs, 2nd ed. (London: J. H. for John Lawrence, 1709), xiv. ↩︎

- Watts did not actually use the phrase “satyrical flourishes” to describe Bradbury, though he did point to the latter’s wit. An example of Bradbury’s “satyrical flourishes” that is perhaps apocryphal, but does suggest both his “levity” and his opinion of Watts’s texts, was related by Milner: “It is said, that an unlucky clerk, on one occasion, having stumbled upon one of Watts’s stanzas, Bradbury got up and reproved him with, ‘Let us have none of Mr. Watts’s whims’” (Life, Times, and Correspondence, 395). Bradbury’s pun (“whims” = “hymns”) seems entirely in keeping with what is known of his character. ↩︎

- Posthumous Works, 2:202. The passage from Watts that Bradbury quotes appears on pp. 251–52 of the first edition of Hymns and Spiritual Songs (London: J. Humfreys for John Lawrence, 1707). ↩︎

- Posthumous Works, 2:203–4. ↩︎

- Posthumous Works, 2:204. ↩︎

- Posthumous Works, 2:210. ↩︎

- Posthumous Works, 2:212. As was the case earlier with Bradbury, Watts slightly misquotes the phrase about showing too much “meekness to an Arian.” ↩︎

- Posthumous Works, 2:216. ↩︎

- Posthumous Works, 2:217. ↩︎

- Hymns and Spiritual Songs (1707), iv, 248. ↩︎

- Posthumous Works, 2:219. ↩︎

- Posthumous Works, 2:228. ↩︎

- Posthumous Works, 2:195. ↩︎

- I. Watts, Hymns and Spiritual Songs, 7th ed. (London: J. H. for R. Ford, 1720), xiv ↩︎